Vice presidency of Aaron Burr

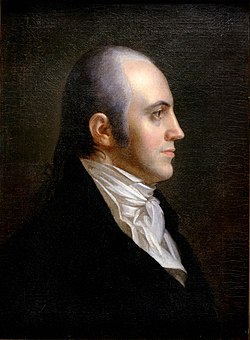

Portrait c. 1801 | |

| Vice presidency of Aaron Burr March 4, 1801 – March 4, 1805 | |

President | |

|---|---|

| Cabinet | See list |

| Party | Democratic-Republican Party[a] |

| Election | 1800 |

|

| |

The vice presidency of Aaron Burr Jr. was the third vice presidency from 1801 to 1805 during Thomas Jefferson's first presidential term. Aaron Burr is mostly remembered for his personal and political conflict with Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton that culminated in the Burr–Hamilton duel where Burr killed Hamilton, and multiple trials for treason in what became known as the Burr conspiracy.

Burr was born to a prominent family in what was then the Province of New Jersey. After studying theology at Princeton University, he began his career as a lawyer before joining the Continental Army as an officer in the American Revolutionary War in 1775, returning practicing law in New York City, where he became a leading politician and helped form the new Jeffersonian Democratic-Republican Party, then represented New York United States Senate from 1791 to 1797. Burr ran as the Democratic-Republican vice presidential candidate in the 1800 election. An Electoral College tie between Burr and Thomas Jefferson resulted in the U.S. House of Representatives voting in Jefferson's favor, with Burr becoming Jefferson's vice president due to receiving the second-highest share of the votes. The debacle lead to the 12th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution which changed the vice presidency to run with the president rather than being awarded to the runner-up candidate. Although Burr maintained that he supported Jefferson, the president never trusted Burr, believing he sought to become president in 1800 instead.

Jefferson relegated Burr to the sidelines of the administration during his presidency. As it became clear that Jefferson would drop Burr from his ticket in the 1804 presidential election, Burr chose to run for the governorship of New York instead. He was backed by members of the Federalist Party and was under patronage of Tammany Hall in the 1804 New York gubernatorial election. Hamilton campaigned vigorously against Burr, causing him to lose the gubernatorial election to Morgan Lewis, a member longtime New York Governor George Clinton's Democratic-Republican who Hamilton endorsed. Burr then challenged Hamilton to a duel at dawn on July 11, 1804. In the duel, Burr shot Hamilton in the abdomen. Hamilton returned fire and hit a tree branch above and behind Burr's head. Hamilton was transported across the Hudson River for treatment in present-day Greenwich Village in New York City, where he died the following day, on July 12, 1804. This also marked the death of Burr's political career, as he was vilified for shooting Hamilton. Burr was indicted for dueling, but all charges against him were dropped. Burr became the first vice president to be dropped from a presidential ticket when George Clinton was selected as Jefferson's running mate in 1804.

After his vice presidency, Burr traveled west to the American frontier, seeking new economic and political opportunities. Jefferson maintained his distrust of Burr, whose secretive activities led to an 1807 arrest in Alabama on charges of treason. Burr was brought to trial more than once for what became known as the Burr conspiracy, an alleged plot to create an independent country led by Burr, but he was acquitted each time. Burr moved to Europe from 1808 to 1812 before returning to the United States, dying on September 14, 1836, at the age of 80.

1800 presidential election

[edit]

In the 1800 United States presidential election, Burr combined the political influence of the Manhattan Company with party campaign innovations to deliver New York's support for Thomas Jefferson.[1] That year, New York's state legislature chose the presidential electors, as they had four years earlier, in 1796, when they gave their support to John Adams. Prior to the April 1800 legislative elections, the State Assembly was controlled by the Federalists. The City of New York elected assembly members on an at-large basis. Burr and Hamilton were the key campaigners for their respective parties. Burr's Democratic-Republican slate of assemblymen was elected, giving the party control of the legislature, which in turn gave New York State's electoral votes to Jefferson and Burr. This drove another wedge between Burr and Hamilton, who had developed a rivalry with Jefferson.[2] Burr enlisted the help of Tammany Hall to win the voting for selection of Electoral College delegates.

Burr was chosen to be the junior member of the Democratic-Republican presidential ticket with Jefferson in the 1800 election, and carried his home state of New York. The Democratic-Republican Party planned to have 72 of their 73 electors vote for Jefferson and Burr, with the remaining elector voting only for Jefferson. The electors failed to execute this plan and Burr and Jefferson were tied with 73 votes each. The Constitution stipulated that if two candidates with an Electoral College majority were tied, the election would be moved to the House of Representatives—which was controlled by the Federalists, at this point, many of whom were loath to vote for Jefferson. Members of the Democratic-Republican Party understood they intended that Jefferson should be president and Burr vice president, but the tied vote required that the final choice be made by the U.S. House of Representatives, with each of the sixteen states having one vote, and nine votes needed for election.[3]

Burr remained quiet publicly, refusing to surrender the presidency to Jefferson, who was seen as the great enemy of the Federalists. Rumors circulated that he and a faction of Federalists were encouraging Democratic-Republican representatives to vote for him, blocking Jefferson's election in the House. However, solid evidence of such a conspiracy was lacking, and historians generally gave Burr the benefit of the doubt. In 2011, however, historian Thomas Baker discovered a previously unknown letter from William P. Van Ness to Edward Livingston, two leading Democratic-Republicans in New York.[4] Van Ness was very close to Burr, serving as his second in the duel with Alexander Hamilton. As a leading Democratic-Republican, Van Ness secretly supported the Federalist plan to elect Burr as president and tried to get Livingston to join.[4] Livingston agreed at first, then reversed himself. Baker argues that Burr probably supported the Van Ness plan: "There is a compelling pattern of circumstantial evidence, much of it newly discovered, that strongly suggests Aaron Burr did exactly that as part of a stealth campaign to compass the presidency for himself."[5] The attempt did not work, however, at least in part because of Livingston's reversal and especially Hamilton's vigorous opposition to Burr.

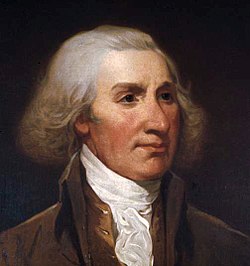

Although Hamilton had a long-standing rivalry with Jefferson stemming from their tenure as members of George Washington's cabinet, he regarded Burr as far more dangerous and used all his influence to ensure Jefferson's election. On the 36th ballot, the House of Representatives gave Jefferson the presidency, with Burr becoming vice president.[6][7]

Relationship with Jefferson

[edit]Jefferson never trusted Burr, so he was effectively shut out of party matters. As vice president, Burr earned praise from some enemies for his even-handedness and his judicial manner as President of the Senate; he fostered some practices for that office that have become time-honored traditions.[8] Burr's judicial manner in presiding over the impeachment trial of Justice Samuel Chase has been credited as helping to preserve the principle of judicial independence that was established by Marbury v. Madison in 1803.[9] One newspaper wrote that Burr had conducted the proceedings with the "impartiality of an angel, but with the rigor of a devil".[10]

Duel with Hamilton

[edit]Overview

[edit]

When it became clear that Jefferson would drop Burr from his ticket in the 1804 election, Burr ran for governor of New York instead. He lost the gubernatorial election to little known Morgan Lewis, in what was the most significant margin of loss in the state's history up to that time.[11] Burr blamed his loss on a personal smear campaign believed to have been orchestrated by his party rivals, including Clinton.[12] Hamilton also opposed Burr, due to his belief that Burr had entertained a Federalist secession movement in New York.[13] In April, the Albany Register published a letter from Dr. Charles D. Cooper to Senator Philip Schuyler, which relayed Hamilton's judgment that Burr was "a dangerous man and one who ought not to be trusted with the reins of government," and claiming to know of "a still more despicable opinion which General Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr".[14] In June, Burr sent this letter to Hamilton, seeking an affirmation or disavowal of Cooper's characterization of Hamilton's remarks.[15]

Hamilton replied that Burr should give specifics of his remarks, not Cooper's, and said he could not answer regarding Cooper's interpretation. A few more letters followed, in which the exchange escalated to Burr's demanding that Hamilton recant or deny any statement disparaging Burr's honor over the past fifteen years.[16] Hamilton, meaning what he said and wanting to ensure his reputation stayed clean for the future, did not.[17] According to historian Thomas Fleming, Burr would have immediately published such an apology, and Hamilton's remaining power in the New York's Federalist party would have been diminished.[18] Burr responded by challenging Hamilton to a duel,[19] personal combat then formalized under rules known as code duello.[20]

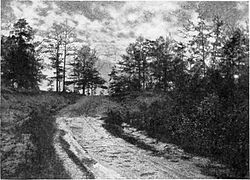

Dueling was outlawed in New York, with bitter punishment awaiting any involved in dueling. It also was illegal in New Jersey, but the criminal ramifications were less severe.[21] On July 11, 1804, the enemies met outside Weehawken, New Jersey, at the same location where Hamilton's oldest son, Philip Hamilton, had been killed in a duel three years earlier. Both men fired, and Hamilton was mortally wounded by a shot just above the hip.[17][21]

The observers disagreed on who fired first. They did agree that there was a three-to-four-second interval between the first and the second shot, raising difficult questions in evaluating the two camps' versions.[22] Historian William Weir speculated that Hamilton might have been undone by his machinations: secretly setting his pistol's trigger to require only a half-pound of pressure as opposed to the usual ten pounds. Weir contends, "There is no evidence that Burr even knew that his pistol had a set trigger."[23] Louisiana State University history professors Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein concur with this, noting that "Hamilton brought the pistols, which had a larger barrel than regular dueling pistols, and a secret hair-trigger, and were therefore much more deadly,"[24] and conclude that "Hamilton gave himself an unfair advantage in their duel, and got the worst of it anyway."[24] However, other accounts state that Hamilton reportedly responded "not this time" when his second, Nathaniel Pendleton, asked whether he would set the hair-trigger feature.[25][26]

David O. Stewart, in his biography of Burr, American Emperor, notes that the reports of Hamilton's intentionally missing Burr with his shot began to be published in newspaper reports in papers friendly to Hamilton only in the days after his death.[27] However, Ron Chernow, in his 2004 biography Alexander Hamilton, states that Hamilton told numerous friends well before the duel of his intention to avoid firing at Burr. Additionally, Hamilton wrote several letters, including a Statement on Impending Duel With Aaron Burr[28] and his last missives to his wife dated before the duel,[29] which also attest to his intention. The second shot, witnesses reported, followed so soon after the first that witnesses could not agree on who fired first. Before the duel proper, Hamilton took a good deal of time getting used to the feel and weight of the pistol and putting on his glasses to see his opponent more clearly. The seconds placed Hamilton so that Burr would have the rising sun behind him, and during the brief duel, one witness reported, Hamilton seemed to be hindered by this placement as the sun was in his eyes.[30]

Each man took one shot. Burr's shot fatally injured Hamilton. While it is unclear whether Hamilton's was purposely fired into the air, Burr's bullet entered Hamilton's abdomen above his right hip, piercing his liver and spine. Hamilton was evacuated to the Manhattan residence of his friend, William Bayard Jr., where he and his family received visitors including Episcopal bishop Benjamin Moore, who gave Hamilton last rites. Burr was charged with multiple crimes, including murder, in New York and New Jersey, but was never tried in either jurisdiction.[30]

Burr fled to South Carolina, where his daughter lived with her family, but soon returned to Philadelphia and then to Washington, D.C. to complete his term as vice president. He avoided New York and New Jersey for a time, but all the charges against him were eventually dropped. In the case of New Jersey, the indictment was thrown out on the basis that, although Hamilton was shot in New Jersey, he died in New York.[30]

Historical Background

[edit]

The duel was the final skirmish of a long conflict between Democratic-Republicans and Federalists. The conflict began in 1791 when Burr won a United States Senate seat from Philip Schuyler, Hamilton's father-in-law, who would have supported Federalist policies. Hamilton was the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury at the time. The Electoral College then deadlocked in the 1800 presidential election, during which Hamilton's maneuvering in the U.S. House of Representatives played a factor in Thomas Jefferson's winning the presidency over Burr.[31] At the time, the candidate who received the most votes was elected president while the candidate with the second most votes became vice president. There were only proto-political parties at the time, as President Washington had lamented in his farewell address in 1796, and joint tickets had not yet become a feature of elections as they are currently.

Hamilton's animosity toward Burr was severe and well-documented in personal letters to his friend and compatriot James McHenry. In a January 4, 1801, letter to McHenry, Hamilton wrote:

Nothing has given me so much chagrin as the Intelligence that the Federal party were thinking seriously of supporting Mr. Burr for president. I should consider the execution of the plan as devoting the country and signing their own death warrant. Mr. Burr will probably make stipulations, but he will laugh in his sleeve while he makes them and will break them the first moment it may serve his purpose.[32]

Hamilton details the many charges that he has against Burr in a more extensive letter written shortly afterward, calling Burr a "profligate, a voluptuary in the extreme", accusing him of corruptly serving the interests of the Holland Land Company while a member of the legislature, criticizing his military commission, accusing him of resigning it under false pretenses, and other serious accusations.[32]

As it became clear that Jefferson would drop Burr from his ticket in the 1804 presidential election, Burr chose to run for the governorship of New York instead.[33] He was backed by members of the Federalist Party and was under patronage of Tammany Hall in the 1804 New York gubernatorial election. Hamilton campaigned vigorously against Burr, causing him to lose the gubernatorial election to Morgan Lewis, a Clintonian Democratic-Republican who Hamilton had endorsed.

Both men had been involved in duels in the past. Hamilton had been involved in more than a dozen affairs of honor[34] prior to his fatal encounter with Burr, including disputes with William Gordon (1779), Aedanus Burke (1790), John Francis Mercer (1792–1793), James Nicholson (1795), James Monroe (1797), Ebenezer Purdy, and George Clinton (1804). He also served as a second to John Laurens in a 1779 duel with General Charles Lee, and to legal client John Auldjo in a 1787 duel with William Pierce.[35] Hamilton also claimed that he had one previous honor dispute with Burr,[36] while Burr stated that there were two.[37]

Additionally, Hamilton's son Philip was killed in a November 23, 1801, duel with George I. Eacker, which was initiated after Philip and his friend Richard Price engaged in hooliganish behavior in Eacker's box at the Park Theatre in Manhattan. This was in response to a speech that Eacker had made on July 3, 1801, which was critical of Hamilton. Philip and his friend both challenged Eacker to duels when he called them "damned rascals".[38] Price's duel, also in Weehawken, New Jersey, resulted in nothing more than four missed shots, and Hamilton advised his son to delope (throw away his shot). However, both Philip and Eacker stood shotless for a minute after the command "present", then Philip leveled his pistol, causing Eacker to fire, mortally wounding Philip and sending his shot awry.

Charles Cooper's letter

[edit]

On April 24, 1804, the Albany Register published a letter opposing Burr's gubernatorial candidacy[39] which was originally sent from Charles D. Cooper to Hamilton's father-in-law, former senator Philip Schuyler.[40] It made reference to a previous statement by Cooper: "General Hamilton and Judge Kent have declared in substance that they looked upon Mr. Burr to be a dangerous man, and one who ought not be trusted with the reins of government." Cooper went on to emphasize that he could describe in detail "a still more despicable opinion which General Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr" at a political dinner.[41]

Burr responded in a letter delivered by William P. Van Ness which pointed particularly to the phrase "more despicable" and demanded "a prompt and unqualified acknowledgment or denial of the use of any expression which would warrant the assertion of Dr. Cooper." Hamilton's verbose reply on June 20, 1804, indicated that he could not be held responsible for Cooper's interpretation of his words (yet he did not fault that interpretation), concluding that he would "abide the consequences" should Burr remain unsatisfied.[42] A recurring theme in their correspondence is that Burr seeks avowal or disavowal of anything that could justify Cooper's characterization, while Hamilton protests that there are no specifics.

Burr replied on June 21, 1804, also delivered by Van Ness, stating that "political opposition can never absolve gentlemen from the necessity of a rigid adherence to the laws of honor and the rules of decorum".[43] Hamilton replied that he had "no other answer to give than that which has already been given". This letter was delivered to Nathaniel Pendleton on June 22 but did not reach Burr until June 25.[44] The delay was due to negotiation between Pendleton and Van Ness in which Pendleton submitted the following paper:

General Hamilton says he cannot imagine what Dr. Cooper may have alluded, unless it were to a conversation at Mr. Taylor's, in Albany, last winter (at which he and General Hamilton were present). General Hamilton cannot recollect distinctly the particulars of that conversation, so as to undertake to repeat them, without running the risk of varying or omitting what might be deemed important circumstances. The expressions are entirely forgotten, and the specific ideas imperfectly remembered; but to the best of his recollection it consisted of comments on the political principles and views of Colonel Burr, and the results that might be expected from them in the event of his election as Governor, without reference to any particular instance of past conduct or private character.[45]

Eventually, Burr issued a formal challenge and Hamilton accepted.[46] Many historians have considered the causes of the duel to be flimsy and have thus characterized Hamilton as "suicidal", Burr as "malicious and murderous", or both.[47] Thomas Fleming offers the theory that Burr may have been attempting to recover his honor by challenging Hamilton, whom he considered to be the only gentleman among his detractors, in response to the slanderous attacks against his character published during the 1804 gubernatorial campaign.[48]

Hamilton's reasons for not engaging in a duel included his roles as father and husband, putting his creditors at risk, and placing his family's welfare in jeopardy, but he felt that it would be impossible to avoid a duel because he had made attacks on Burr that he was unable to recant, and because of Burr's behavior prior to the duel. He attempted to reconcile his moral and religious reasons and the codes of honor and politics. Joanne Freeman speculates that Hamilton intended to accept the duel and throw away his shot in order to satisfy his moral and political codes.[49]

Duel

[edit]

In the early morning of July 11, 1804, Burr and Hamilton departed from Manhattan by separate boats and rowed across the Hudson River to a spot known as the Heights of Weehawken, New Jersey, a popular dueling ground below the towering cliffs of the Palisades.[50] Dueling had been prohibited in both New York and New Jersey, but Hamilton and Burr agreed to go to Weehawken because New Jersey was not as aggressive as New York in prosecuting dueling participants. The same site was used for 18 known duels between 1700 and 1845, and it was not far from the site of the 1801 duel that resulted in the death of Hamilton's eldest son Philip Hamilton.[51][52] They also took steps to give all witnesses plausible deniability in an attempt to shield themselves from prosecution. For example, the pistols were transported to the island in a portmanteau, enabling the rowers to say under oath that they had not seen any pistols. They also stood with their backs to the duelists.[53]

Burr, William Peter Van Ness (his second), Matthew L. Davis, another man often identified as John Swarthout, and the rowers all reached the site at 6:30 a.m., whereupon Swarthout and Van Ness started to clear the underbrush from the dueling ground. Hamilton, Judge Nathaniel Pendleton (his second), and Dr. David Hosack arrived a few minutes before seven. Lots were cast for the choice of position and which second should start the duel. Both were won by Hamilton's second, who chose the upper edge of the ledge for Hamilton, facing the city.[54] However, Joseph Ellis claims that Hamilton had been challenged and therefore had the choice of both weapon and position. Under this account, Hamilton himself chose the upstream or north side position.[55]

Some first-hand accounts of the duel agree that two shots were fired, but some say only Burr fired, and the seconds disagreed on the intervening time between them. It was common for both principals in a duel to deliberately miss or fire their shot into the ground to exemplify courage (a practice known as deloping). The duel could then come to an end. Hamilton apparently fired a shot above Burr's head. Burr returned fire and hit Hamilton in the lower abdomen above the right hip.[56] The large-caliber lead ball ricocheted off Hamilton's third or second false rib, fracturing it and causing considerable damage to his internal organs, particularly his liver and diaphragm, before lodging in his first or second lumbar vertebra. According to Pendleton's account, Hamilton collapsed almost immediately, dropping the pistol involuntarily, and Burr moved toward him in a speechless manner (which Pendleton deemed to be indicative of regret) before being hustled away behind an umbrella by Van Ness because Hosack and the rowers were already approaching.[56]

It is entirely uncertain which principal fired first, as both seconds' backs were to the duel in accordance with the pre-arranged regulations so that they could testify that they "saw no fire". After much research to determine the actual events of the duel, historian Joseph Ellis thinks,

Hamilton did fire his weapon intentionally, and he fired first. But he aimed to miss Burr, sending his ball into the tree above and behind Burr's location. In so doing, he did not withhold his shot, but he did waste it, thereby honoring his pre-duel pledge. Meanwhile, Burr, who did not know about the pledge, did know that a projectile from Hamilton's gun had whizzed past him and crashed into the tree to his rear. According to the principles of the code duello, Burr was perfectly justified in taking deadly aim at Hamilton and firing to kill.

David Hosack's account

[edit]Hosack wrote his account on August 17, about one month after the duel had taken place. He testified that he had only seen Hamilton and the two seconds disappear "into the wood", heard two shots, and rushed to find a wounded Hamilton. He also testified that he had not seen Burr, who had been hidden behind an umbrella by Van Ness.[57] He gives a very clear picture of the events in a letter to William Coleman:

When called to him upon his receiving the fatal wound, I found him half sitting on the ground, supported in the arms of Mr. Pendleton. His countenance of death I shall never forget. He had at that instant just strength to say, "This is a mortal wound, doctor;" when he sunk away, and became to all appearance lifeless. I immediately stripped up his clothes, and soon, alas I ascertained that the direction of the ball must have been through some vital part. His pulses were not to be felt, his respiration was entirely suspended, and, upon laying my hand on his heart and perceiving no motion there, I considered him as irrecoverably gone. I, however, observed to Mr. Pendleton, that the only chance for his reviving was immediately to get him upon the water. We therefore lifted him up, and carried him out of the wood to the margin of the bank, where the bargemen aided us in conveying him into the boat, which immediately put off. During all this time I could not discover the least symptom of returning life. I now rubbed his face, lips, and temples with spirits of hartshorn, applied it to his neck and breast, and to the wrists and palms of his hands, and endeavoured to pour some into his mouth.[58]

Hosack goes on to say that Hamilton had revived after a few minutes, either from the hartshorn or fresh air. He finishes his letter:

Soon after recovering his sight, he happened to cast his eye upon the case of pistols, and observing the one that he had had in his hand lying on the outside, he said, "Take care of that pistol; it is undischarged, and still cocked; it may go off and do harm. Pendleton knows" (attempting to turn his head towards him) "that I did not intend to fire at him." "Yes," said Mr. Pendleton, understanding his wish, "I have already made Dr. Hosack acquainted with your determination as to that." He then closed his eyes and remained calm, without any disposition to speak; nor did he say much afterward, except in reply to my questions. He asked me once or twice how I found his pulse; and he informed me that his lower extremities had lost all feeling, manifesting to me that he entertained no hopes that he should long survive.[58]

Statement to the press

[edit]Pendleton and Van Ness issued a press statement about the events of the duel which pointed out the agreed-upon dueling rules and events that transpired. It stated that both participants were free to open fire once they had been given the order to present. After first fire had been given, the opponent's second would count to three, whereupon the opponent would fire or sacrifice his shot.[59] Pendleton and Van Ness disagree as to who fired the first shot, but they concur that both men had fired "within a few seconds of each other" (as they must have; neither Pendleton nor Van Ness mentions counting down).[59]

In Pendleton's amended version of the statement, he and a friend went to the site of the duel the day after Hamilton's death to discover where Hamilton's shot went. The statement reads:

They ascertained that the ball passed through the limb of a cedar tree, at an elevation of about twelve feet and a half, perpendicularly from the ground, between thirteen and fourteen feet from the mark on which General Hamilton stood, and about four feet wide of the direct line between him and Col. Burr, on the right side; he having fallen on the left.[60]

Hamilton's intentions

[edit]Hamilton wrote a letter before the duel titled Statement on Impending Duel with Aaron Burr[61] in which he stated that he was "strongly opposed to the practice of dueling" for both religious and practical reasons. "I have resolved," it continued, "if our interview is conducted in the usual manner, and it pleases God to give me the opportunity, to reserve and throw away my first fire, and I have thoughts even of reserving my second fire."[62][63]

Hamilton regained consciousness after being shot and told Dr. Hosack that his gun was still loaded and that "Pendleton knows I did not mean to fire at him." This is evidence for the theory that Hamilton intended not to fire, honoring his pre-duel pledge, and only fired accidentally upon being hit.[60] Such an intention would have violated the protocol of the code duello and, when Burr learned of it, he responded: "Contemptible, if true."[64] Hamilton could have thrown away his shot by firing into the ground, thus possibly signaling Burr of his purpose.

Modern historians have debated to what extent Hamilton's statements and letter represent his true beliefs, and how much of this was a deliberate attempt to permanently ruin Burr if Hamilton were killed. An example of this may be seen in what one historian has considered to be deliberate attempts to provoke Burr on the dueling ground:

Hamilton performed a series of deliberately provocative actions to ensure a lethal outcome. As they were taking their places, he asked that the proceedings stop, adjusted his spectacles, and slowly, repeatedly, sighted along his pistol to test his aim.[65]

Burr's intentions

[edit]There is evidence that Burr intended to kill Hamilton.[66] The afternoon after the duel, he was quoted as saying that he would have shot Hamilton in the heart had his vision not been impaired by the morning mist.[67] English philosopher Jeremy Bentham met with Burr in England in 1808, four years after the duel, and Burr claimed to have been certain of his ability to kill Hamilton. Bentham concluded that Burr was "little better than a murderer."[68]

There is also evidence in Burr's defense. Had Hamilton apologized for his "more despicable opinion of Mr. Burr",[69] all would have been forgotten. However, the code duello required that injuries which needed an explanation or apology must be specifically stated. Burr's accusation was so unspecific that it could have referred to anything that Hamilton had said over 15 years of political rivalry. Despite this, Burr insisted on an answer.[70]

Burr knew of Hamilton's public opposition to his presidential run in 1800. Hamilton made confidential statements against him, such as those enumerated in his letter to Supreme Court Justice John Rutledge. In the attachment to that letter, Hamilton argued against Burr's character on numerous scores: he suspected Burr "on strong grounds of having corruptly served the views of the Holland Company;" "his very friends do not insist on his integrity"; "he will court and employ able and daring scoundrels;" he seeks "Supreme power in his own person" and "will in all likelihood attempt a usurpation," and so forth.[71]

Pistols

[edit]

The pistols used in the duel belonged to Hamilton's brother-in-law John Barker Church, who was a business partner of both Hamilton and Burr.[72] Later legend claimed that these pistols were the same ones used in a 1799 duel between Church and Burr in which neither man was injured.[73][74] Burr, however, wrote in his memoirs that he supplied the pistols for his duel with Church, and that they belonged to him.[75][74]

The Wogdon & Barton dueling pistols incorporated a hair-trigger feature that could be set by the user.[73][76] Hamilton was familiar with the weapons and would have been able to use the hair trigger. However, Pendleton asked him before the duel whether he would use the "hair-spring", and Hamilton reportedly replied, "Not this time."[54] Hamilton's son Philip and George Eacker likely used the Church weapons in the 1801 duel in which Philip died, three years before the Burr–Hamilton duel.[73] They were kept at Church's estate Belvidere until the late 19th century.[77] During this time one of the pistols was modified, with its original flintlock mechanism replaced by a more modern caplock mechanism. This was done by Church's grandson for use in the American Civil War. Consequently, the pistols are no longer identical.[78]

The pair were sold in 1930 to the Chase Manhattan Bank, now part of JP Morgan Chase, which traces its descent back to the Manhattan Company founded by Burr, and are on display in the bank's headquarters at 270 Park Avenue in New York City.[79]

Aftermath

[edit]

After being attended by Hosack, the mortally wounded Hamilton was taken to the home of William Bayard Jr. in the present-day Greenwich Village section of New York City, where he was given communion by Bishop Benjamin Moore.[81][82] He died the next day after seeing his wife Elizabeth and their children, in the presence of more than 20 friends and family members; he was buried in the Trinity Churchyard Cemetery in Manhattan. Hamilton was an Episcopalian at the time of his death.[83]

Most pistol duels in the early 1800s did not end in fatalities. [84] Thus the fact that Hamilton and his son Philip both died in pistol duels three years apart was notable. The events had striking similarities: the two duels were fought within several miles of each other, both men were struck in the lower abdomen above the right hip, both were attended by the same physician, and both men were transported back to Manhattan after being wounded. [85] Both men died the day after the duel.

Following the duel, Burr fled to St. Simons Island, Georgia, where he stayed at the plantation of Pierce Butler, but he soon returned to Washington, D.C. to complete his term as vice president.[86][87]

Burr was charged with murder in New York and New Jersey, but neither charge ever reached trial. In Bergen County, New Jersey in November 1804, a grand jury indicted Burr for murder,[50] but the New Jersey Supreme Court quashed it on a motion from Colonel Ogden.[88][who?] He presided over the impeachment trial of Samuel Chase "with the dignity and impartiality of an angel, but with the rigor of a devil", according to a Washington newspaper. Burr's heartfelt farewell speech to the Senate in March 1805 moved some of his harshest critics to tears.[89]

Contacts with the British

[edit]While Burr was still vice president, in 1804 he met with Anthony Merry, the British Minister to the United States.[citation needed] As Burr told several of his colleagues, he suggested to Merry that the British might regain power in the Southwest if they contributed guns and money to his expedition.[citation needed] Burr offered to detach Louisiana from the Union in exchange for a half million dollars and a British fleet in the Gulf of Mexico.[citation needed] Merry wrote, "It is clear Mr. Burr... means to endeavour to be the instrument for effecting such a connection—he has told me that the inhabitants of Louisiana ... prefer having the protection and assistance of Great Britain."[90] "Execution of their design is only delayed by the difficulty of obtaining previously an assurance of protection & assistance from some foreign power."[90]

Thomas Jefferson was re-elected in 1804, but Burr was not nominated by the Democratic-Republicans to be Jefferson's running mate, and his term as vice president ended in March 1805.[citation needed] In November of that year, Burr again met with Merry and asked for two or three ships of the line and money. Merry informed Burr that London had not yet responded to Burr's plans which he had forwarded the previous year. Merry gave him fifteen hundred dollars. Those Merry worked for in London expressed no interest in furthering an American secession. In the spring of 1806, Burr had his final meeting with Merry. In this meeting Merry informed Burr that still no response had been received from London. Burr told Merry, "with or without such support it certainly would be made very shortly."[91] Merry was recalled to Britain on June 1, 1806.

List of tie-breaking votes cast

[edit]This section needs expansion with: tie breaking votes cast. You can help by adding to it. (April 2025) |

1804 presidential election

[edit]Burr was not nominated to a second term as Jefferson's running mate in the 1804 election, and fellow New Yorker George Clinton replaced Burr as vice president on March 4, 1805. Burr's farewell speech on March 2, 1805,[92] moved some of his harshest critics in the Senate to tears.[93] But the 20-minute speech was never recorded in full,[94] and has been preserved only in short quotes and descriptions of the address, which defended the American system of government.[92]

Burr conspiracy

[edit]Traveling to Louisiana Territory

[edit]

In 1805 Burr conceived plans to emigrate, which he claimed was for the purpose of taking possession of land in the Texas Territories leased to him by the Spanish (the lease was granted, and copies still exist). That year Burr traveled from Pittsburgh, down the Ohio River, to the Louisiana Territory.[95]

General James Wilkinson was one of Burr's key partners. The Commanding General of the United States Army at the time, Wilkinson was known for his attempt to separate Kentucky and Tennessee from the union during the 1780s.[96] Burr persuaded President Thomas Jefferson to appoint Wilkinson to the position of Governor of the Louisiana Territory in 1805.[97] Wilkinson would later send a letter to Jefferson that Wilkinson claimed was evidence of Burr's treason.[98]

In the spring of 1805, Burr met with Harman Blennerhassett, who proved valuable in helping Burr further his plan. He provided friendship, support, and most importantly, access to Blennerhassett Island which he owned on the Ohio River, about 2 miles (3 km) below what is now Parkersburg, West Virginia. On July 27, 1805, Burr stopped at a stand near the Duck River along the Natchez Trace to attend a party celebrating the signing of the Treaty of the Chickasaw Nation.[99]

In 1806, Blennerhassett offered to provide Burr with substantial financial support. Burr and his co-conspirators used this island as a storage space for men and supplies. Burr tried to recruit volunteers to enter Spanish territories. In New Orleans, he met with the Mexican associates, a group of criollos whose objective was to conquer Mexico (still part of New Spain at the time). Burr was able to gain the support of New Orleans' Catholic bishop for his expedition into Mexico. Reports of Burr's plans first appeared in newspaper reports in August 1805, which suggested that Burr intended to raise a western army and "to form a separate government."[citation needed]

In early 1806, Burr contacted the Spanish diplomat and future Prime Minister, Carlos Martínez de Irujo y Tacón and told him that his plan was not just western secession, but the capture of Washington, D.C. Irujo wrote to his masters in Madrid about the coming "dismemberment of the colossal power which was growing at the very gates" of New Spain.[100] Irujo gave Burr a few thousand dollars to get things started. The Spanish government in Madrid took no action.

Following the events in Kentucky, Burr returned to the West later in 1806 to recruit more volunteers for a military expedition down the Mississippi River. He began using Blennerhassett Island in the Ohio River to store men and supplies. The Governor of Ohio grew suspicious of the activity there, and ordered the state militia to raid the island and seize all supplies. Blennerhassett escaped with one boat, and he met Burr at the operation's headquarters on the Cumberland River. With a significantly smaller force, the two headed down the Ohio to the Mississippi River and New Orleans. Wilkinson had vowed to supply troops at New Orleans, but he concluded that the conspiracy was bound to fail, and rather than providing troops, Wilkinson revealed Burr's plan to President Jefferson.

Arrest

[edit]

In February and March 1806, the federal attorney for Kentucky, Joseph Hamilton Daveiss, wrote Jefferson several letters warning him that Burr planned to provoke a rebellion in Spanish-held parts of the West, in order to join them to areas in the Southwest and form an independent nation under his rule.[citation needed] Similar accusations were published against local Democratic-Republicans in the Frankfort, Kentucky, newspaper Western World.[citation needed] Jefferson dismissed Daveiss' accusations against Burr, a Democratic-Republican, as politically motivated.[citation needed]

Daveiss brought charges against Burr, claiming that he intended to make war with Mexico.[citation needed] However, a grand jury declined to indict Burr, who was defended by the young attorney Henry Clay.[101]

By mid-1806, Jefferson and his cabinet began to take more notice of reports of political instability in the West. Their suspicions were confirmed when General Wilkinson sent the president correspondence which he had received from Burr. The text of the letter that was used as the principal evidence against Burr is as follows:

Yours postmarked 13th May is received. I have obtained funds, and have actually commenced the enterprise. Detachments from different points under different pretences will rendezvous on the Ohio, 1st November—everything internal and external favors views—protection of England is secured. T[ruxton] is gone to Jamaica to arrange with the admiral on that station, and will meet at the Mississippi—England—Navy of the United States are ready to join, and final orders are given to my friends and followers—it will be a host of choice spirits. Wilkinson shall be second to Burr only—Wilkinson shall dictate the rank and promotion of his officers. Burr will proceed westward 1st August, never to return: with him go his daughter—the husband will follow in October with a corps of worthies. Send forthwith an intelligent and confidential friend with whom Burr may confer. He shall return immediately with further interesting details—this is essential to concert and harmony of the movement. Send a list of all persons known to Wilkinson west of the mountains, who could be useful, with a note delineating their characters. By your messenger send me four or five of the commissions of your officers, which you can borrow under any pretence you please. They shall be returned faithfully. Already are orders to the contractor given to forward six months' provisions to points Wilkinson may name—this shall not be used until the last moment, and then under proper injunctions: the project is brought to the point so long desired: Burr guarantees the result with his life and honor—the lives, the honor and fortunes of hundreds, the best blood of our country. Burr's plan of operations is to move rapidly from the falls on the 15th of November, with the first five hundred or one thousand men, in light boats now constructing for that purpose—to be at Natchez between the 5th and 15th of December—then to meet Wilkinson—then to determine whether it will be expedient in the first instance to seize on or pass by Baton Rouge. On receipt of this send Burr an answer—draw on Burr for all expenses, &c. The people of the country to which we are going are prepared to receive us—their agents now with Burr say that if we will protect their religion, and will not subject them to a foreign power, that in three weeks all will be settled. The gods invite to glory and fortune—it remains to be seen whether we deserve the boon. The bearer of this goes express to you—he will hand a formal letter of introduction to you from Burr, a copy of which is hereunto subjoined. He is a man of inviolable honor and perfect discretion—formed to execute rather than project—capable of relating facts with fidelity, and incapable of relating them otherwise. He is thoroughly informed of the plans and intentions of Burr, and will disclose to you as far as you inquire, and no further—he has imbibed a reverence for your character, and may be embarrassed in your presence—put him at ease and he will satisfy you —29th July.[102]

In an attempt to preserve his good name, Wilkinson edited the letters. They had been sent to him in cypher, and he altered the letters to testify to his own innocence and Burr's guilt. He warned Jefferson that Burr was "meditating the overthrow of [his] administration" and "conspiring against the State." Jefferson alerted Congress of the plan, and ordered the arrest of anyone who conspired to attack Spanish territory.[103] He warned authorities in the West to be aware of suspicious activities. Convinced of Burr's guilt, Jefferson ordered his arrest.

Burr continued his excursion down the Mississippi with Blennerhassett and the small army of men which they had recruited in Ohio. They intended to reach New Orleans, but in Bayou Pierre, 30 miles north of Natchez, they learned that a bounty was out for Burr's capture. Burr and his men surrendered at Bayou Pierre, and Burr was taken into custody. Charges were brought against him in the Mississippi Territory, but Burr escaped into the wilderness. He was recaptured on February 19, 1807, and was taken back to Virginia to stand trial.[104]

Trial

[edit]

Burr was charged with treason because of the alleged conspiracy and stood trial in Richmond, Virginia. He was acquitted due to lack of evidence of treason, as Chief Justice John Marshall did not consider conspiracy without actions sufficient for conviction. A Revolutionary War hero, U.S. Senator, New York State Attorney General and Assemblyman, and finally vice president under Jefferson, Burr adamantly denied and vehemently resented all charges against his honor, his character or his patriotism.[105]

Burr was charged with treason for assembling an armed force to take New Orleans and separate the Western from the Atlantic states. He was also charged with high misdemeanor for sending a military expedition against territories belonging to Spain. George Hay, the prosecuting U.S. Attorney, compiled a list of over 140 witnesses, one of whom was Andrew Jackson, who previously invited Burr to stay at his house when he was on the run. To encourage witnesses to cooperate with the prosecution, Thomas Jefferson gave Hay blank pardons containing Jefferson's signature and the discretion to issue them to all but "the grossest offenders"; Jefferson later amended these instructions to include even those the prosecution believed to be most culpable, if that meant the difference in convicting Burr.[106]

Burr's trial brought into question the ideas of executive privilege, state secrets privilege, and the independence of the executive. Burr's lawyers, including John Wickham, asked Chief Justice Marshall to subpoena Jefferson, claiming that they needed documents from Jefferson to present their case accurately. Jefferson proclaimed that, as president, he was "Reserving the necessary right of the President of the U S to decide, independently of all other authority, what papers, coming to him as President, the public interests permit to be communicated, & to whom."[107] He insisted that all relevant papers had been made available, and that he was not subject to this writ because he held executive privilege. He also argued that he should not be subject to the commands of the judiciary, because the Constitution guaranteed the executive branch's independence from the judicial branch. Marshall decided that the subpoena could be issued despite Jefferson's position of presidency. Though Marshall vowed to consider Jefferson's office and avoid "vexatious and unnecessary subpoenas", his ruling was significant because it suggested that, like all citizens, the president was subject to the law.[108]

Marshall had to consider the definition of treason and whether intent was sufficient for conviction, rather than action. Marshall ruled that because Burr had not committed an act of war, he could not be found guilty (see Ex parte Bollman); the First Amendment guaranteed Burr the right to voice opposition to the government. To merely suggest war or to engage in a conspiracy was not enough.[109] To be convicted of treason, Marshall ruled, an overt act of participation must be proven with evidence. Intention to divide the union was not an overt act: "There must be an actual assembling of men for the treasonable purpose, to constitute a levying of war."[110] Marshall further supported his decision by indicating that the Constitution stated that two witnesses must see the same overt act against the country. Marshall narrowly construed the definition of treason provided in Article III of the Constitution; he noted that the prosecution had failed to prove that Burr had committed an "overt act" as the Constitution required. As a result, the jury acquitted the defendant.[111]

Witness testimony was inconsistent, and one of the few witnesses to testify to an "overt act of treason", Jacob Allbright, perjured himself in the process.[112] Allbright testified that militia General Edward Tupper raided Blennerhasset Island and attempted to arrest Harman Blennerhasset, but had been stopped by armed followers of Burr, who raised their weapons at Tupper to threaten him. In fact, Tupper had previously provided a deposition stating that when he visited the island, he had no arrest warrant, had not attempted to effect an arrest of anyone, had not been threatened, and had a pleasant visit with Blennerhasset.

The historians Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein write that Burr "was not guilty of treason, nor was he ever convicted, because there was no evidence, not one credible piece of testimony, and the star witness for the prosecution had to admit that he had doctored a letter implicating Burr."[113] In contrast, lawyer and author David O. Stewart concludes that Burr's intention included "acts that constituted the crime of treason, but that in the context of 1806, "the moral verdict is less clear." He points out that neither invasion of Spanish lands nor secession of American territory was considered treasonous by most Americans at the time, in view of the fluid boundaries of the American Southwest at that time, combined with the widespread expectation (shared by President Jefferson) that the United States might well divide into two nations.[114]

Aftermath

[edit]Wilkinson's alteration of Burr's letter was clearly intended to minimize Wilkinson's culpability. His forgery and obviously self-serving testimony had the effect of making Burr seem to be the victim of an overzealous government. The grand jury nearly produced enough votes in favor of indicting Wilkinson for misprision of treason.[115] The foreman, John Randolph said of Wilkinson that he was a "mammoth of iniquity", the "most finished scoundrel", and "the only man I ever saw who was from the bark to the very core a villain."[116]

Immediately following the acquittal, straw effigies of Burr, Blennerhassett, Martin, and Marshall were hanged and burned by angry mobs.[117] Burr, with his prospects for a political career quashed, left the United States for a self-imposed exile in Europe until 1812. He first traveled to England in 1808 in an attempt to gain support for a revolution in Mexico. He was ordered out of the country, so he traveled to France to ask for the support of Napoleon. He was denied and found himself too poor to pay his way home. Finally, in 1812, he was able to sail back to the United States on a French ship.

Upon returning to the United States, he assumed the surname of "Edwards" and returned to New York to resume his law practice. He married Eliza Jumel, the wealthy socialite widow of Stephen Jumel, but she left him after only four months of marriage due to his land speculations and financial mismanagement which reduced her finances.[118] Historians attribute his self-imposed exile and using a different surname in part to escape from his creditors, as he was deeply in debt. Burr died on September 14, 1836, the same day that his divorce from his wife was granted.[118]

Following his involvement with Burr, James Wilkinson was twice investigated by Congress on issues related to the West. Following an unsuccessful court-martial ordered by President James Madison in 1811, he was allowed to return to his military command in New Orleans.[119]

When the conspiracy was uncovered, Blennerhassett's mansion[120] and island were occupied and allegedly plundered by members of the Virginia militia. He fled with his family, but he was twice arrested. The second time he was held in prison until Burr's acquittal. Blennerhassett went to Mississippi, where he became a cotton planter. Later he moved with his family to Canada, where he practiced law and lived in Montreal. Late in life, Blennerhassett left for Europe and died in Guernsey on February 2, 1831.[121]

Andrew Jackson's early affiliation with Burr followed him for next 40 years. In 1842, a "Justitia" writing in the New-York American connected the Burr conspiracy and Jackson's association with Sam Houston, writing:[122]

"I will now say in general terms, that the committee that undertook the defense of Gen. Jackson, at the period of his first nomination for the presidency, against the charge that he was a participator in Burr's conspiracy, do not even pretend to clear him of that part of it relating to the conquest of Mexico, but only of what relates to the dismemberment of this Union. And had they thus attempted, Jackson's own declaration would have tended to confute them: for, in a letter of his to Gov. Claiborne, of Louisiana, dated Nov. 12, 1806, he says: "I hate the Dons; I WOULD DELIGHT TO SEE MEXICO REDUCED." Still more effectually would his acts have confuted them. He was an agent of Burr; he received money from him to conduct his agency; he built boats for him; obtained for him stores and provisions; was on the most intimate terms with him; and, long after the explosion of Burr's schemes, whatever they might have been, continued still so much in his good graces, as to be his favorite candidate for the presidency of the United States! So, likewise, in relation to Gen. Houston, the recent conspirator against Mexico. Gen. Jackson was fully aware of all his movements in getting up his Texan expedition; notwithstanding which, he entertained him in the most cordial manner, as he had previously done to Burr; and instead of adopting measures to check his operations, countenanced him in every way he could, as far as he dared to do, under existing circumstances. Whence this coincidence? How happened it, that the two arch-conspirators against the integrity of the Mexican republic, should, at different and distant periods, make Jackson's domicil their rendezvous? Because, to use his own words, "he hated the Dons, and would delight to see Mexico reduced."

Legacy

[edit]

Although Burr is often remembered primarily for his duel with Hamilton, his establishment of guides and rules for the first impeachment trial set a high bar for behavior and procedures in the Senate chamber, many of which are followed today.[123][124]

Historian Nancy Isenberg, seeking to explain Burr's negative image in modern times, wrote that his portrayal as a villain is actually the result of a smear campaign invented by his political enemies centuries ago, and then disseminated in newspapers, pamphlets and personal letters during and after his lifetime. According to Isenberg, pop-cultural portraits of Burr have repeated these distortions, transforming him into the quintessential "bad guy" of early American history.[125] Stuart Fisk Johnson describes Burr as progressive thinker and doer, a brave military patriot and brilliant lawyer who helped establish some of the physical infrastructure and guiding legal principles which helped in the founding of America.[126]

A lasting consequence of Burr's role in the election of 1800 was the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which changed how vice presidents were chosen. As was evident from the 1800 election, the situation could quickly arise where the vice president, as the defeated presidential candidate, could not work well with the president. The Twelfth Amendment required that electoral votes be cast separately for president and vice president.[127]

Burr is also sometimes seen as one of the Founding Fathers of the United States,[128] although this characterization is unusual.[129]

Representation in literature and popular culture

[edit]

- Edward Everett Hale's 1863 story "The Man Without a Country" is about a fictional co-conspirator of Burr's in the Southwest and Mexico, who is placed in internal exile (in the custody of the United States Navy) for his crimes.[130]

- Gore Vidal's Burr: A Novel (1973) is part of his Narratives of Empire series.[131]

- PBS's American Experience episode "The Duel" (2000) chronicled the events that led to the Burr–Hamilton duel.[132]

- Burr is a principal character in the 2015 biographical musical Hamilton, written by Lin-Manuel Miranda and inspired by historian Ron Chernow's 2004 biography of Hamilton.[133] Leslie Odom Jr. won the Tony Award for Best Actor in a Musical for his portrayal of Aaron Burr on Broadway.[134] Giles Terera portrayed Aaron Burr in the West End production, winning the Laurence Olivier Award in the same category.[135]

- In the alternative history anthology Alternate Presidents (1992) by Mike Resnick. "The War of '07" by Jayge Carr, Aaron Burr is elected the third president in 1800 against Thomas Jefferson, establishes an alliance with Napoleon Bonaparte, and creates a family dictatorship. Aaron Burr serves as president for nine terms until his death on September 14, 1836. His grandson and final vice president Aaron Burr Alston becomes the fourth president of the United States.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Most commonly referred to as the Republican Party at the time

References

[edit]- ^ Murphy 2008, pp. 233–266.

- ^ Elkins & McKitrick 1995, p. 733.

- ^ Paulsen & Paulsen 2017, p. 53.

- ^ a b Baker 2011, pp. 553–598.

- ^ Baker 2011, p. 556.

- ^ Ferling 2004.

- ^ Sharp 2010.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 862.

- ^ McDonald 1992.

- ^ Lamb 1921, p. 500.

- ^ Stewart 2011, p. 29.

- ^ "The New York Govenor's Race". Retrieved March 10, 2025 – via PBS.

- ^ Kerber 1980, p. 148.

- ^ Fleming 1999, p. 233.

- ^ Fleming 1999, p. 284.

- ^ "To Alexander Hamilton from Aaron Burr". June 21, 1804. Retrieved March 10, 2025 – via Founders Online.

- ^ a b "Hamilton-Burr Duel". May 8, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2025 – via National Park Service.

- ^ Fleming 1999, pp. 287–289.

- ^ "To Alexander Hamilton from Aaron Burr". June 22, 1804. Retrieved March 6, 2025 – via Founders Online.

- ^ "The History of Dueling in America". Retrieved March 6, 2025 – via PBS.

- ^ a b "Burr—Hamilton Duel". Retrieved March 13, 2025 – via Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Ellis 2000, pp. 20–47.

- ^ Weir, William (2003). "Interview in Weehawken, Mystery in the West". Written With Lead: America's most famous and notorious gunfights from the Revolutionary War to today. New York: Cooper Square Press. p. 29. ISBN 0815412894.

- ^ a b Isenberg & Burstein 2011.

- ^ Winfield, Charles H. (1874). History of the County of Hudson, New Jersey from Its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time. New York: Kennard and Hay. Chapter 8, "Duels." pp. 219.

- ^ Brookhiser, Richard (2000). Alexander Hamilton, American. Simon and Schuster. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-43913-545-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ Stewart 2011, p. 35-38.

- ^ Hamilton 1804a.

- ^ Hamilton 1804b.

- ^ a b c Stewart, (2011).

- ^ See, for example, Alexander Hamilton to Harrison Gray Otis (December 23, 1800).

- ^ a b Bernard C. Steiner and James McHenry, The life and correspondence of James McHenry (Cleveland: Burrows Brothers Co., 1907).

- ^ "Aaron Burr slays Alexander Hamilton in duel".

- ^ Freeman, Joanne B. (2002). Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic. Yale University Press. pp. 326–327.

- ^ Freeman, 1996, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Nathaniel Pendleton to Van Ness. June 26, 1804. Hamilton Papers, 26:270.

- ^ Burr to Charles Biddle; July 18, 2004. Papers of Aaron Burr, 2: 887.

- ^ Fleming 1000, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Cooper, Charles D. April 24, 1804. Albany Register.

- ^ Cooper to Philip Schuyler. Hamilton Papers. April 23, 1804. 26: 246.

- ^ Hamilton, John Church (1879). Life of Alexander Hamilton. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ "From Alexander Hamilton to Aaron Burr, June 20, 1804". Founders.archives.gov. June 29, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ^ "To Alexander Hamilton from Aaron Burr, June 21, 1804". Founders.archives.gov. June 29, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ^ "From Alexander Hamilton to Aaron Burr, June 22, 1804". Founders.archives.gov. June 29, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ^ Winfield, 1875, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Winfield, 1875, p. 217.

- ^ Freeman, 1996, p. 290.

- ^ Fleming, p. 281

- ^ Freeman, Joanne (1996). Dueling as Politics: Reinterpreting the Burr–Hamilton Duel.

- ^ a b Buescher, John. "Burr–Hamilton Duel." Teachinghistory.org Archived September 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed July 11, 2011.

- ^ Demontreux, 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Chernow, Ron (2005). Alexander Hamilton. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303475-9.

- ^ Chernow, p. 700.

- ^ a b Winfield, 1874, p. 219.

- ^ Ellis, Joseph. Founding Brothers. p. 24

- ^ a b Winfield, 1874, pp. 219–220.

- ^ William P. Van Ness vs. The People. 1805.

- ^ a b Dr. David Hosack to William Coleman, August 17, 1804.

- ^ a b "Document: Joint statement on the Duel < A Biography of Alexander Hamilton (1755–1804) < Biographies < American History From Revolution To Reconstruction and beyond". Odur.let.rug.nl. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ^ a b Nathaniel Pendleton's Amended Version of His and William P. Ness's Statement of July 11, 1804.

- ^ The letter is not dated, but the consensus among Hamilton's contemporaries (including Burr) suggests that it was written July 10, 1804, the night before the duel. See Freeman, 1996, note 1.

- ^ Hamilton, Alexander. "Statement on Impending Duel with Aaron Burr, (June 28, – July 10, 1804)". Founders Online.

- ^ Hamilton, 1804, 26:278.

- ^ Joseph Wheelan, Jefferson's Vendetta: The Pursuit of Aaron Burr and the Judiciary, New York, Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2005, ISBN 0-7867-1437-9, p. 90

- ^ Kennedy, Roger G. (2000). Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson: A Study in Character. Oxford University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0199728220. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ^ Winfield. 1874. p. 220.

- ^ N.Y. Spectator. July 28, 1824.

- ^ Sabine. 1857. p. 212.

- ^ "Steven C. Smith. My Friend Hamilton – Whom I Shot" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2007. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ McDonald, Forrest (1979). Alexander Hamilton: A Biography. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393300482. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- ^ Holland, Josiah Gilbert; Gilder, Richard Watson (1900). The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ "The two boats rowed back to New York City". www.aaronburrassociation.org. Archived from the original on June 2, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ a b c Lindsay, Merrill (November 1976). "Pistols Shed Light on Famed Duel". Smithsonian: 94–98. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- ^ a b Alexander Hamilton, by Ron Chernow, p. 590

- ^ Burr, Aaron; Davis, Matthew Livingston (1837). Memoirs of Aaron Burr: With Miscellaneous Selections from His Correspondence, Volume 1. Harper & Brothers. p. 417. ISBN 9780836952131. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ For the United States Bicentennial in 1976, Chase Manhattan allowed the pistols to be removed and lent to the U.S. Bicentennial Society of Richmond. A subsequent article in the Smithsonian magazine said that close examination of the pistols had revealed a secret hair trigger. ("Pistols shed light on famed duel" Archived March 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine from the Smithsonian magazine; November 1976) However, English dueling pistols had been customarily fitted with hair triggers, known as set triggers, for 20 years before the duel, and pistols made by Robert Wogdon were no exception. They cannot, therefore, be said to have secret hair triggers. The British Duelling Pistol; John Atkinson, Arms and Armour Press; 1978)

- ^ Robert Bromeley and Mrs. Patrick W. Harrington (August 1971). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Belvidere". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved June 14, 2009. See also: "Unfiled NHL Nomination Form for Villa Belvidere". Archived from the original on August 14, 2012.

- ^ Hahn, Fritz (May 25, 2018). "For the first time, the pistol used to kill Alexander Hamilton is on public view in D.C." The Washington Post. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ "JPMorgan's Expanding Footprint". DealBook. The New York Times. March 16, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2014.

- ^ "Mourn, Oh Columbia! Thy Hamilton is Gone to That 'bourn from which no traveler returns'". The Adams Centinel. Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, U.S.: Robert Harper. July 25, 1804. p. 3.

- ^ Fleming, Thomas. Duel – Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr and the Future of America, New York: Basic Books, 1999, pp. 328–329

- ^ "The Last Hours of Alexander Hamilton". Trinity Church Wall Street. July 9, 2014.

- ^ Chernow.[page needed]

- ^ "The History of Dueling in America". pbs.org. Retrieved April 10, 2025.

- ^ Fraga, Kaleena (September 14, 2023). "The Tragic Story Of Philip Hamilton, The Doomed Son Of Founding Father Alexander Hamilton". Retrieved April 10, 2025.

- ^ April 29, 2016. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ Kemble, Frances Anne (1984) [1st pub. 1961]. "Editor's Introduction". In Scott, John A. (ed.). Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838–1839. University of Georgia Press. pp. lvii. ISBN 0-8203-0707-6.

- ^ Centinel of Freedom. November 24, 1807, cited in Winfield, 1874, p. 220.

- ^ "Indicted Vice President Bids Senate Farewell – March 2, 1805". United States Senate. Historical Minutes. 2003. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Melton (2002), p. 66

- ^ Melton (2002), p. 96

- ^ a b "U.S. Senate: Aaron Burr, 3rd Vice President (1801–1805)". www.senate.gov. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ "that "most uncommon man"". The Nashville Tennessean Magazine. October 26, 1952. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Gordon L. (1953). "Aaron burr's farewell address". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 39 (3): 273–282. doi:10.1080/00335635309381878. "Except for some of his court-room speeches [...] no verbatim reports of his speeches are extant."

- ^ Memoirs of Aaron Burr - Google Boeken. Kessinger. June 2004. ISBN 9781419133572. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ Linklater, Andro (2009). An Artist in Treason: The Extraordinary Double Life of General James Wilkinson. Walker Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8027-1720-7.

- ^ Bruns, Roger A. Congress investigates: a documented history, 1792-1974. Chelsea House Publishers, 1975.

- ^ "Founders Online: To Thomas Jefferson from James Wilkinson, 13 September 1807". founders.archives.gov. Retrieved April 9, 2025.

- ^ Atkinson, James R. (2010). Splendid Land, Splendid People: The Chickasaw Indians to Removal. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-0-8173-8337-4.

- ^ Melton (2002), p. 92

- ^ David Stephen Heidler & Jeanne T. Heidler (2011). Henry Clay: The Essential American. Random House. pp. 57–59. ISBN 9780812978957.

- ^ "Ciphered Letter of Aaron Burr to General James Wilkinson". Famous Trials. University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law.

- ^ "Special Message on the Burr Conspiracy". Special Reports to Congress. January 22, 1807.

- ^ Pickett, Albert James (1900). History of Alabama and Incidentally of Georgia and Mississippi, from the Earliest Period. Webb Book Company. p. 492. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ Peter Charles Hoffer, The treason trials of Aaron Burr (U. Press of Kansas, 2008)

- ^ Stewart 2011, p. 233.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas. "Thomas Jefferson to George Hay, 12 June 1807". University of Chicago.

- ^ Hoffer, The treason trials of Aaron Burr (U. Press of Kansas, 2008)

- ^ Newmyer, R. Kent (2007). John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court. LSU Press. pp. 199–200. ISBN 9780807132494.

- ^ Marshall, John. "Ex parte Bollman & Swartwout". The Founders' Constitution. The University of Chicago. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ^ Newmyer (2007), pp. 200–201

- ^ "Testimony in the Trial of Aaron Burr: Day 2 (August 19, 1807)". www.famous-trials.com.

- ^ Burstein, Andrew; Isenberg, Nancy (January 4, 2011). "What Michele Bachmann doesn't know about history". Salon.com.

- ^ Stewart 2011, pp. 302–303

- ^ Harris, Matthew L.; Buckley, Jay H. (2012). Zebulon Pike, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-8061-4243-2.

- ^ Isenberg, Nancy (2004). Beyond the Founders: New Approaches to the Political History of the Early American Republic. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-8078-2889-2.

- ^ American Citizen, 5 December 1807

- ^ a b "Aaron Burr". Historic Valley Forge. National Center for the American Revolution/Valley Forge Historical Society. n.d. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ Junius P. Rodriguez, ed. (2002). The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 352–53. ISBN 9781576071885.

- ^ The Island where it happened ohioec.org [dead link]

- ^ Ohio Archæological and Historical Quarterly. 1901. p. 119.

- ^ "Mexico and Texas from the New-York American". National Anti-Slavery Standard. December 8, 1842. p. 1. Retrieved February 2, 2025.

- ^ "Aaron Burr". Retrieved March 13, 2025 – via Historical Society of the Courts of New York.

- ^ "Aaron Burr". Retrieved March 13, 2025 – via Constitutional Law Reporter.

- ^ Isenberg, Nancy. "Liberals love Alexander Hamilton. But Aaron Burr was a real progressive hero". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Stuart Fisk (February 3, 2017). "Defending the honor of Aaron Burr". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Bailey 2007, p. 196.

- ^ "Aaron Burr". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved February 26, 2025.

- ^ Bomboy, Scott (June 15, 2020). "How Aaron Burr changed the Constitution". National Constitution Center.

- ^ Hale, Edward Everett (1889) [1st pub. The Atlantic Monthly Dec. 1863]. The Man Without a Country: And Other Tales. Boston: Roberts Brothers.

- ^ Vidal, Gore (2011) [1st pub. 1973]. Burr: A Novel. Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 978-0307798411.

- ^ PBS 2000.

- ^ Wood, Gordon S. (January 14, 2016). "Federalists on Broadway". New York Review of Books. pp. 10–13.

- ^ Viagas, Robert (June 12, 2016). "Hamilton Tops Tony Awards With 11 Wins". Archived from the original on January 30, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2025 – via Playbill.

- ^ Guardian Stage (March 6, 2018). "Olivier awards 2018: complete list of nominations". The Guardian. Retrieved March 24, 2025.

Works cited

[edit]- Adams, John; Adams, Charles Francis (1856). "To James Lloyd. Quincy, February 17, 1815". The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States. Vol. 10. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Co.

- Adamson, Bruce Campbell (1988). For Which We Stand: The Life and Papers of Rufus Easton. Aptos, CA: Self-published.

- Allen, Oliver E. (1993). The Tiger: The Rise and Fall of Tammany Hall. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 0-201-62463-X.

- Bailey, Jeremy D. (2007). Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139466295.

- Baker, Thomas N. (Winter 2011). "'An Attack Well Directed': Aaron Burr Intrigues for the Presidency". Journal of the Early Republic. 31 (4). University of Pennsylvania Press: 553–598. doi:10.1353/jer.2011.0073. JSTOR 41261652. S2CID 144183161.

- Berkin, Carol; Miller, Christopher L.; Cherny, Robert W.; Gormly, James L.; Egerton, Douglas R. & Woestman, Kelly (2013) [1st pub. Houghton Mifflin: 1995]. Making America: A History of the United States (Brief 6th ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1133317692.

- Beveridge, Albert J. (2000). The Life of John Marshall: Conflict and Construction 1800–1815. Beard Books. p. 538. ISBN 978-1-58798-049-7.

- Beyer, Rick (2017). Rivals Unto Death: Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. Hachette Books. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-316-50496-6.

- Bray, Samuel (2005). "Not Proven: Introducing a Third Verdict". University of Chicago Law Review. 72 (4). SSRN 1339222.

- Brown, Maria Ward (1901). The Life of Dan Rice. Long Branch, NJ: Self-published.

- Buescher, John (November 11, 2010). "Burr-Hamilton Duel". Ask a Historian. Teachinghistory.org. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014.

- Burr, Aaron (1837). Davis, Matthew Livingston (ed.). Memoirs of Aaron Burr: With Miscellaneous Selections from His Correspondence. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 387 n.1.

- Chernow, Ron (2004). Alexander Hamilton. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-1-1012-0085-8.

- Collins, Paul (2013). Duel with the Devil. Crown.

- Daschle, Tom; Robbins, Charles (2013). The U.S. Senate: Fundamentals of American Government. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-1250027559.

- Documents of the Senate of the State of New York. Vol. 9. Albany, NY: J. B. Lyon Company. 1902.

- Elkins, Stanley; McKitrick, Eric (1995). The Age of Federalism.

- Ellis, Joseph J. (2000). Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0375405440.

- Fairfield, Jane (1860). The Autobiography of Jane Fairfield. Boston: Bazin and Ellsworth.

- Ferling, John (2004). Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516771-9.

- Fleming, Thomas (1999). Duel: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and the Future of America. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465017379.

- Hamilton, Alexander. "Statement on Impending Duel with Aaron Burr (June 28 – July 10, 1804)". Founders Online.

- Hamilton, Alexander. "To Elizabeth Hamilton from Alexander Hamilton, July 10, 1804". Founders Online (letter).

- Hoffer, Peter Charles (2008). The Treason Trials of Aaron Burr. U. Press of Kansas.

- Ip, Greg (October 5, 2005). "Aaron Burr fans find unlikely ally in black descendant". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008.

- Isenberg, Nancy (2007). Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-20236-4.

- Isenberg, Nancy; Burstein, Andrew (January 4, 2011). "What Michele Bachmann doesn't know about history". Salon.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014.

- James, Edward T.; James, Janet Wilson; Boyer, Paul S., eds. (1971). "Burr, Theodosia". Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary. Harvard University Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-674-62734-5.

- Kerber, Linda K. (1980) [1st pub. 1970]. Federalists in Dissent: Imagery and Ideology in Jeffersonian America. New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801492122.

- Kip, William Ingraham (February 1867). "Recollections of John Vanderlyn, the Artist". The Atlantic Monthly. 19. Boston: Ticknor and Fields.

- Koeppel, Gerard T. (2001). Water for Gotham: A History. Princeton University Press. p. 183. ISBN 0-691-08976-0.

- Lamb, Martha J. (1921) [1st pub. A.S. Barnes: 1877]. History of the City of New York: Its Origin, Rise and Progress. Vol. 3. New York: Valentine's Manual.

- Leitch, Alexander (1978). A Princeton Companion. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400870011.

- Lomask, Milton (1979). Aaron Burr: The Years from Princeton to Vice President, 1756–1805. Vol. 1. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Lomask, Milton (1982). Aaron Burr: The Conspiracy and Years of Exile, 1805–1836. Vol. 2. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Maillard, Mary (2013). "'Faithfully Drawn from Real Life': Autobiographical Elements in Frank J. Webb's The Garies and Their Friends". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 137 (3): 261–300. doi:10.5215/pennmaghistbio.137.3.0261. JSTOR 10.5215/pennmaghistbio.137.3.0261.

- McDonald, Forrest (June 14, 1992). "The Senate Was Their Jury". Review. The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014.

- McFarland, Philip (1979). Sojourners. New York: Atheneum.

- Murphy, Brian Phillips (2008). "'A Very Convenient Instrument': The Manhattan Company, Aaron Burr, and the Election of 1800". William and Mary Quarterly. 65 (2).

- Myers, Gustavus (1901). The History of Tammany Hall. Gustavus Myers. p. 15.

- "Vanderlyn, John". National Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018.

- The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record. New York Genealogical and Biographical Society. 1881–1882.

- Newmyer, R. Kent (2012). The Treason Trial of Aaron Burr: Law, Politics, and the Character Wars of the New Nation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107022188.

- Nolan, Charles J. (1980). Aaron Burr and the American Literary Imagination. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313212567.

- Office of Art and Archives (n.d.). "Burr, Aaron". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. U.S. Congress. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014.

- Bureau of Public Affairs. "Thomas Sumter Jr. (1768–1840)". Office of the Historian. United States Department of State. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012.

- Oppenheimer, Margaret (2015). The Remarkable Rise of Eliza Jumel: A Story of Marriage and Money in the Early Republic. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-61373-383-7.

- Parmet, Herbert S. & Hecht, Marie B. (1967). Aaron Burr: Portrait of an Ambitious Man. Macmillan.

- Parton, James (1861). The Life and Times of Aaron Burr. New York: Mason Brothers. p. 124.