Portal:Stars

IntroductionA star is a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of light. The most prominent stars have been categorised into constellations and asterisms, and many of the brightest stars have proper names. Astronomers have assembled star catalogues that identify the known stars and provide standardized stellar designations. The observable universe contains an estimated 1022 to 1024 stars. Only about 4,000 of these stars are visible to the naked eye—all within the Milky Way galaxy. A star's life begins with the gravitational collapse of a gaseous nebula of material largely comprising hydrogen, helium, and trace heavier elements. Its total mass mainly determines its evolution and eventual fate. A star shines for most of its active life due to the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium in its core. This process releases energy that traverses the star's interior and radiates into outer space. At the end of a star's lifetime, fusion ceases and its core becomes a stellar remnant: a white dwarf, a neutron star, or—if it is sufficiently massive—a black hole. Stellar nucleosynthesis in stars or their remnants creates almost all naturally occurring chemical elements heavier than lithium. Stellar mass loss or supernova explosions return chemically enriched material to the interstellar medium. These elements are then recycled into new stars. Astronomers can determine stellar properties—including mass, age, metallicity (chemical composition), variability, distance, and motion through space—by carrying out observations of a star's apparent brightness, spectrum, and changes in its position in the sky over time. Stars can form orbital systems with other astronomical objects, as in planetary systems and star systems with two or more stars. When two such stars orbit closely, their gravitational interaction can significantly impact their evolution. Stars can form part of a much larger gravitationally bound structure, such as a star cluster or a galaxy. (Full article...) Selected star - Photo credit: User:Mysid

VY Canis Majoris (VY CMa) is a red hypergiant star located in the constellation Canis Major. One of the largest stars and also one of the most luminous of its type, it has a radius of approximately 1,420 ± 120 solar radii (equal to a diameter of 13.2 astronomical units, or about 1,976,640,000 km), and is situated about 1.2 kiloparsecs (3,900 light-years) from Earth. VY CMa is a single star categorized as a semiregular variable and has an estimated period of 2,000 days. It has an average density of 5 to 10 mg/m3. If placed at the center of the Solar System, VY Canis Majoris's surface would extend beyond the orbit of Jupiter, although there is still considerable variation in estimates of the radius, with some making it larger than the orbit of Saturn. The first known record of VY Canis Majoris is in the star catalogue of Jérôme Lalande, on March 7, 1801. The catalogue listed VY CMa as a 7th magnitude star. Further studies on its apparent magnitude during the 19th century showed that the star has been fading since 1850. Since 1847, VY CMa has been known to be a red star. During the 19th century, observers measured at least six discrete components to VY CMa, suggesting the possibility that it is a multiple star. These discrete components are now known to be bright areas in the surrounding nebula. Visual observations in 1957 and high-resolution imaging in 1998 showed that VY CMa does not have a companion star. Selected article - Photo credit: JAXA/NASA

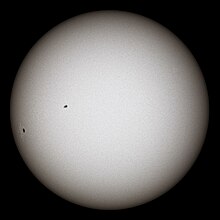

A solar flare is a large explosion in the Sun's atmosphere that can release as much as 6 × 1025 joules of energy. The term is also used to refer to similar phenomena in other stars, where the term stellar flare applies. Solar flares affect all layers of the solar atmosphere (photosphere, corona, and chromosphere), heating plasma to tens of millions of kelvins and accelerating electrons, protons, and heavier ions to near the speed of light. They produce radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum at all wavelengths, from radio waves to gamma rays. Most flares occur in active regions around sunspots, where intense magnetic fields penetrate the photosphere to link the corona to the solar interior. Flares are powered by the sudden (timescales of minutes to tens of minutes) release of magnetic energy stored in the corona. If a solar flare is exceptionally powerful, it can cause coronal mass ejections. X-rays and UV radiation emitted by solar flares can affect Earth's ionosphere and disrupt long-range radio communications. Direct radio emission at decimetric wavelengths may disturb operation of radars and other devices operating at these frequencies. Solar flares were first observed on the Sun by Richard Christopher Carrington and independently by Richard Hodgson in 1859 as localized visible brightenings of small areas within a sunspot group. Stellar flares have also been observed on a variety of other stars. The frequency of occurrence of solar flares varies, from several per day when the Sun is particularly "active" to less than one each week when the Sun is "quiet". Large flares are less frequent than smaller ones. Solar activity varies with an 11-year cycle (the solar cycle). At the peak of the cycle there are typically more sunspots on the Sun, and hence more solar flares. Selected image - Photo credit: NASA

The Pinwheel Galaxy (also known as Messier 101 or NGC 5457) is a face-on spiral galaxy about 27 million light-years away in the constellation Ursa Major, discovered by Pierre Méchain. On February 28, 2006, NASA and the ESA released a very detailed image of Pinwheel Galaxy, which was the largest and most detailed image of a galaxy by Hubble Space Telescope at the time. The image was composed from 51 individual exposures, plus some extra ground-based photos. M101 is a relatively large galaxy compared to the Milky Way. With a diameter of 170,000 light-years it is nearly twice the size of the Milky Way. It has a disk mass on the order of 100 billion solar masses, along with a small bulge of about 3 billion solar masses. Did you know?

SubcategoriesTo display all subcategories click on the ►

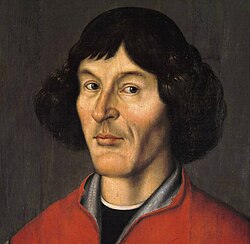

Selected biography - Photo credit: Portrait from Toruń

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was the first astronomer to formulate a comprehensive heliocentric cosmology, which displaced the Earth from the center of the universe. Nicolaus Copernicus was born on 19 February 1473 in the city of Toruń (Thorn) in Royal Prussia, part of the Kingdom of Poland. Copernicus' epochal book, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), published just before his death in 1543, is often regarded as the starting point of modern astronomy and the defining epiphany that began the scientific revolution. His heliocentric model, with the Sun at the center of the universe, demonstrated that the observed motions of celestial objects can be explained without putting Earth at rest in the center of the universe. His work stimulated further scientific investigations, becoming a landmark in the history of science that is often referred to as the Copernican Revolution. Among the great polymaths of the Renaissance, Copernicus was a mathematician, astronomer, physician, quadrilingual polyglot, classical scholar, translator, artist, Catholic cleric, jurist, governor, military leader, diplomat and economist. Among his many responsibilities, astronomy figured as little more than an avocation – yet it was in that field that he made his mark upon the world.

TopicsThings to do

Related portalsAssociated WikimediaThe following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

Discover Wikipedia using portals |