Portal:Scotland/Selected articles 2

| Main Page | Selected articles 1 | Selected articles 2 | Selected biographies | Selected quotes | Selected pictures | Featured Content | Categories & Topics |

Selected articles 61

The first castle at Edzell was a timber motte and bailey structure, built to guard the mouth of Glenesk, a strategic pass leading north into the Highlands. The motte, or mound, is still visible 300 metres (980 ft) south-west of the present castle, and dates from the 12th century. It was the seat of the Abbott, or Abbe, family, and was the centre of the now-vanished original village of Edzell. The Abbotts were succeeded as lords of Edzell by the Stirlings of Glenesk, and the Stirlings in turn by the Lindsays. In 1358, Sir Alexander de Lindsay, third son of David Lindsay of Crawford, married the Stirling heiress, Katherine Stirling. Alexander's son, David, was created Earl of Crawford in 1398.

Selected articles 62

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most historically and architecturally important castles in Scotland. The castle sits atop an intrusive crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill geological formation. It is surrounded on three sides by steep cliffs, giving it a strong defensive position. Its strategic location, guarding what was, until the 1890s, the farthest downstream crossing of the River Forth, has made it an important fortification in the region from the earliest times.

Most of the principal buildings of the castle date from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. A few structures remain from the fourteenth century, while the outer defences fronting the town date from the early eighteenth century.

Before the union with England, Stirling Castle was also one of the most used of the many Scottish royal residences, very much a palace as well as a fortress. Several Scottish Kings and Queens have been crowned at Stirling, including Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1542, and others were born or died there.

There have been at least eight sieges of Stirling Castle, including several during the Wars of Scottish Independence, with the last being in 1746, when Bonnie Prince Charlie unsuccessfully tried to take the castle. Stirling Castle is a Scheduled Ancient Monument, and is now a tourist attraction managed by Historic Environment Scotland.Castle Hill, on which Stirling Castle is built, forms part of the Stirling Sill, a formation of quartz-dolerite around 350 million years old, which was subsequently modified by glaciation to form a "crag and tail". It is likely that this natural feature was occupied at an early date, as a hill fort is located on Gowan Hill, immediately to the east.

The Romans bypassed Stirling, building a fort at Doune instead, but the rock may have been occupied by the Maeatae at this time. It may later have been a stronghold of the Manaw Gododdin, and has also been identified with a settlement recorded in the 7th and 8th centuries as Urbs Iudeu, where King Penda of Mercia besieged King Oswy of Bernicia in 655. The area came under Pictish control after the defeat of the Northumbrians at the Battle of Dun Nechtain thirty years later. However, there is no archaeological evidence for occupation of Castle Hill before the late medieval period.

Selected articles 63

The Royal Observatory, Edinburgh (ROE) is an astronomical institution located on Blackford Hill in Edinburgh. The site is owned by the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC). The ROE comprises the UK Astronomy Technology Centre (UK ATC) of STFC, the Institute for Astronomy of the School of Physics and Astronomy of the University of Edinburgh, and the ROE Visitor Centre.

The observatory carries out astronomical research and university teaching; design, project management, and construction of instruments and telescopes for astronomical observatories; and teacher training in astronomy and outreach to the public. The ROE Library includes the Crawford Collection of books and manuscripts gifted in 1888 by the 26th Earl of Crawford. Before it moved to the present site in 1896, the Royal Observatory was located on Calton Hill, close to the centre of Edinburgh, at what is now known as the City Observatory.

The University of Edinburgh in 1785 and by Royal Warrant of George III created the Regius Chair of Astronomy and appointed Robert Blair first Regius Professor of Astronomy. After his death in 1828 the position remained vacant until 1834. In 1811 private citizens had founded the Astronomical Institution of Edinburgh with John Playfair – professor of natural philosophy – as its president. The Institution acquired grounds on Calton Hill to build an observatory, which was designed by John's nephew William Henry Playfair; it remains to this day as the Playfair building of the City Observatory.

During his visit of Edinburgh in 1822, George IV bestowed upon the observatory the title of "Royal Observatory of King George the Fourth". In 1834 – with Government funding – the instrumentation of the observatory was completed. This cleared the way to uniting the observatory with the Regius Chair, and Thomas Henderson was appointed the first Astronomer Royal for Scotland and second Regius Professor of Astronomy. The main instruments of the new observatory were a 6.4-inch (16 cm) transit telescope and a 3.5-inch (9 cm) azimuth circle.

Selected articles 64

Lochleven Castle is a ruined castle on an island in Loch Leven, in the Perth and Kinross local authority area of Scotland. Possibly built around 1300, the castle was the site of military action during the Wars of Scottish Independence (1296–1357). In the latter part of the 14th century, the castle was granted to William Douglas, 1st Earl of Douglas, by his uncle. It remained in the Douglases' hands for the next 300 years. Mary, Queen of Scots, was imprisoned there in 1567–68, and forced to abdicate as queen, before escaping with the help of her gaoler's family. In 1588, the queen's gaoler inherited the title of Earl of Morton, and moved away from the castle. In 1675, Sir William Bruce, an architect, bought the castle and used it as a focal point for his garden; it was never again used as a residence.

The remains of the castle are protected as a scheduled monument in the care of Historic Environment Scotland. Lochleven Castle is open to the public in summer, and access is available by ferry.A castle may have been built on Castle Island as early as 1257, when King Alexander III of Scotland, then 16 years old, was forcibly brought there by his regents. During the First War of Scottish Independence (1296–1328), the invading English army held the castle, then named Lochleven Castle; it lies at a strategically important position between the towns of Edinburgh, Stirling and Perth. Part of the present fortification, the curtain wall, may date from this time period and may have been built by the occupying English. The castle was captured by the Scots before the end of the 13th century, possibly by the forces of William Wallace.

English forces laid siege to Lochleven in 1301, but the garrison was relieved in the same year when the siege was broken by Sir John Comyn. King Robert the Bruce (reigned 1306–1329) is known to have visited the castle in 1313 and again in 1323. Following Bruce's death, the English invaded again, and in 1335 laid siege to Lochleven Castle in support of the pretender Edward Balliol (d. 1364). According to the 14th-century chronicle of John of Fordun, the English attempted to flood the castle by building a dam across the outflow of the loch; the water level rose, but after a month the captain of the English force, Sir John de Stirling, left the area to attend the festival of Saint Margaret of Scotland, and the defenders, under Alan de Vipont, took advantage of his absence to come out of the castle under cover of night, and damage the dam, causing it to collapse and flood the English camp. However, this account has been doubted by later historians.

Selected articles 65

Balmoral Castle (/bælˈmɒrəl/) is a large estate house in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and a residence of the British royal family. It is near the village of Crathie, 9 miles (14 km) west of Ballater and 50 miles (80 km) west of Aberdeen.

The estate and its original castle were bought from the Farquharson family in 1852 by Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria. Soon afterwards the house was found to be too small and the current Balmoral Castle was commissioned. The architect was William Smith of Aberdeen, and his designs were amended by Prince Albert. Balmoral remains the private property of the monarch and is not part of the Crown Estate. It was the summer residence of Queen Elizabeth II, who died there on 8 September 2022.

The castle is an example of Scottish baronial architecture, and is classified by Historic Environment Scotland as a category A listed building. The new castle was completed in 1856 and the old castle demolished shortly thereafter.

The Balmoral Estate has been added to by successive members of the royal family, and now covers an area of 21,725 hectares (53,684 acres) of land. It is a working estate, including grouse moors, forestry and farmland, as well as managed herds of deer, Highland cattle, sheep and ponies.Balmoral is pronounced /bælˈmɒrəl/ or sometimes locally /bəˈmɒrəl/. It was first recorded as 'Bouchmorale' in 1451, and it was pronounced [baˈvɔrəl] by local Scottish Gaelic speakers. The first element in the name is thought to be the Gaelic both, meaning "a hut", but the second part is uncertain. Adam Watson and Elizabeth Allan wrote in The Place Names of Upper Deeside that the second part meant "big spot (of ground)". Alexander MacBain suggested this was originally the Pictish *mor-ial, "big clearing" (cf. Welsh mawr-ial). Alternatively, the second part could be a saint's name.

Selected articles 66

Skara Brae /ˈskærə ˈbreɪ/ is a stone-built Neolithic settlement, located on the Bay of Skaill in the parish of Sandwick, on the west coast of Mainland, the largest island in the Orkney archipelago of Scotland. It consisted of ten clustered houses, made of flagstones, in earthen dams that provided support for the walls; the houses included stone hearths, beds, and cupboards. A primitive sewer system, with "toilets" and drains in each house, included water used to flush waste into a drain and out to the ocean.

The site was occupied from roughly 3180 BC to around 2500 BC and is Europe's most complete Neolithic village. Skara Brae gained UNESCO World Heritage Site status as one of four sites making up "The Heart of Neolithic Orkney". Older than Stonehenge and the Great Pyramids of Giza, it has been called the "Scottish Pompeii" because of its excellent preservation.

Care of the site is the responsibility of Historic Environment Scotland which works with partners in managing the site: Orkney Islands Council, NatureScot (Scottish Natural Heritage), and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Visitors to the site are welcome during much of the year.In the winter of 1850, a severe storm hit Scotland, causing widespread damage and over 200 deaths. In the Bay of Skaill, the storm stripped earth from a large irregular knoll. (The name Skara Brae is a corruption of Skerrabra or Styerrabrae, which originally referred to the knoll.) When the storm cleared, local villagers found the outline of a village consisting of several small houses without roofs. William Graham Watt of Skaill House, a son of the local laird who was a self-taught geologist, began an amateur excavation of the site, but after four houses were uncovered, work was abandoned in 1868.

Selected articles 67

Edinburgh Zoo (Scottish Gaelic: Sù Dhùn Èideann), formerly the Scottish National Zoological Park, is an 82-acre (33 ha) non-profit zoological park in the Corstorphine area of Edinburgh, Scotland.

The zoo is positioned on the south-facing slopes of Corstorphine Hill, giving extensive views of the city. Established in 1913, and owned by the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, it receives over 600,000 visitors a year, which makes it one of Scotland's most popular paid-for tourist attractions. As well as catering for tourists and locals, the zoo is involved in many scientific pursuits, such as captive breeding of endangered animals, researching into animal behaviour, and active participation in various conservation programmes around the world.

Edinburgh Zoo was the first zoo in the world to house and breed penguins. It is the only zoo in Britain to house Queensland koalas and, until December 2023, giant pandas. The zoo is a member of the British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums (BIAZA), the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA), the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA), and the Association of Scottish Visitor Attractions. It has also been granted four stars by the Scottish Tourism Board. The zoo gardens boast one of the most diverse tree collections in the Lothians.The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS) was founded as a registered charity in 1909 by an Edinburgh lawyer, Thomas Hailing Gillespie. The Corstorphine Hill site was purchased by the Society with help from the Edinburgh Town Council in early 1913. Gillespie's vision of what a zoological park should be was modelled after the 'open design' of Tierpark Hagenbeck in Hamburg, a zoo which promoted a more spacious and natural environment for the animals, and stood in stark contrast to the steel cages typical of the menageries built during the Victorian era. The design and layout were largely the product of Patrick Geddes and his son-in-law Frank Mears but Sir Robert Lorimer was involved in some of the more architectural elements including the remodelling of Corstorphine House at its centre.

Selected articles 68

The Isle of Mull or simply Mull (Scottish Gaelic: Muile [ˈmulə] ⓘ) is the second-largest island of the Inner Hebrides (after Skye) and lies off the west coast of Scotland in the council area of Argyll and Bute.

Covering 875.35 square kilometres (337.97 sq mi), Mull is the fourth-largest island in Scotland. Between 2011 and 2022 the population increased from 2,800 to 3,063. It has the eighth largest island population in Scotland. In the summer, these numbers are augmented by an influx of many tourists. Much of the year-round population lives in the colourful main settlement of Tobermory.

There are two distilleries on the island: the Tobermory distillery, formerly named Ledaig, produces single malt Scotch whisky and another, opened in 2019 and located in the vicinity of Tiroran, which produces Whitetail Gin. Mull is host to numerous sports competitions, notably the Highland Games competition, held annually in July. The isle is home to four castles, including the towering castle of Duart and the keep of Moy Castle. On the south coast, a stone circle is located in the settlement of Lochbuie.Mull has a coastline of 480 km (300 mi), and its climate is moderated by the Gulf Stream. The island has a mountainous core; the highest peak on the island is Ben More, which reaches 966 m (3,169 ft). Various peninsulas, which are predominantly moorland, radiate from the centre.

Selected articles 69

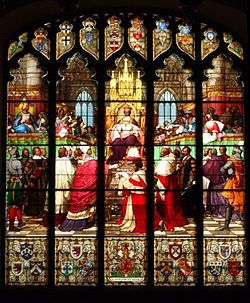

Scone Palace /ˈskuːn/ is a Category A-listed historic house near the village of Scone and the city of Perth, Scotland. Ancestral seat of Earls of Mansfield, built in red sandstone with a castellated roof, it is an example of the Gothic Revival style in Scotland.

Scone was originally the site of an early Christian church, and later an Augustinian priory. Scone Abbey, in the grounds of the Palace, for centuries held the Stone of Scone upon which the early Kings of Scotland were crowned. Robert the Bruce was crowned at Scone in 1306 and the last coronation was of Charles II, when he accepted the Scottish crown in 1651.

Scone Abbey was severely damaged in 1559 during the Scottish Reformation after a mob whipped up by the famous reformer, John Knox, came to Scone from Dundee. Having survived the Reformation, the Abbey in 1600 became a secular Lordship (and home) within the parish of Scone, Scotland. The Palace has thus been home to the Earls of Mansfield for over 400 years. During the early 19th century the Palace was enlarged by the architect William Atkinson. In 1802, David William Murray, 3rd Earl of Mansfield, commissioned Atkinson to extend the Palace, recasting the late 16th-century Palace of Scone. The 3rd Earl tasked Atkinson with updating the old Palace whilst maintaining characteristics of the medieval Gothic abbey buildings it was built upon, with the majority of work finished by 1807.

The Palace and its grounds, which include a collection of fir trees and a star-shaped maze, are open to the public.Selected articles 70

Scotland during the Roman Empire refers to the protohistorical period during which the Roman Empire interacted within the area of modern Scotland. Despite sporadic attempts at conquest and government between the first and fourth centuries AD, most of modern Scotland, inhabited by the Caledonians and the Maeatae, was not incorporated into the Roman Empire with Roman control over the area fluctuating.

In the Roman imperial period, the area of Caledonia lay north of the River Forth, while the area now called England was known as Britannia, the name also given to the Roman province roughly consisting of modern England and Wales and which replaced the earlier Ancient Greek designation as Albion. Roman legions arrived in the territory of modern Scotland around AD 71, having conquered the Celtic Britons of southern Britannia over the preceding three decades. Aiming to complete the Roman conquest of Britannia, the Roman armies under Quintus Petillius Cerialis and Gnaeus Julius Agricola campaigned against the Caledonians in the 70s and 80s. The Agricola, a biography of the Roman governor of Britannia by his son-in-law Tacitus mentions a Roman victory at "Mons Graupius" which became the namesake of the Grampian Mountains but whose identity has been questioned by modern scholarship. In 2023 a lost Roman road built by Julius Agricola was rediscovered in Drip close to Stirling: it has been described as "the most important road in Scottish history".

Agricola then seems to have repeated an earlier Greek circumnavigation of the island by Pytheas and received submission from local tribes, establishing the Roman limes of actual control first along the Gask Ridge, and then withdrawing south of a line from the Solway Firth to the River Tyne, i.e. along the Stanegate. This border was later fortified as Hadrian's Wall. Several Roman commanders attempted to fully conquer lands north of this line, including a second-century expansion that was fortified as the Antonine Wall.Selected articles 71

The Battle of Culloden took place on 16 April 1746, near Inverness in the Scottish Highlands. A Jacobite army under Charles Edward Stuart was decisively defeated by a British government force commanded by the Duke of Cumberland, thereby ending the Jacobite rising of 1745.

Charles landed in Scotland in July 1745, seeking to restore his father James Francis Edward Stuart to the British throne. He quickly won control of large parts of Scotland, and an invasion of England reached as far south as Derby before being forced to turn back. However, by April 1746, the Jacobites were short of supplies, facing a superior and better equipped opponent.

Charles and his senior officers decided their only option was to stand and fight. When the two armies met at Culloden, the battle was brief, lasting less than an hour, with the Jacobites suffering an overwhelming and bloody defeat. This effectively ended both the 1745 rising, and Jacobitism as a significant element in British politics.The Jacobite rising of 1745 began on 23 July when Charles Edward Stuart landed in the Western Isles, and launched an attempt to reclaim the British throne for the exiled House of Stuart. After their victory at Prestonpans in September, the Jacobites controlled much of Scotland, and Charles persuaded his colleagues to invade England. The Jacobite army reached Derby, before successfully retreating back across the border.

Selected articles 72

Islay (/ˈaɪlə/ ⓘ EYE-lə; Scottish Gaelic: Ìle, Scots: Ila) is the southernmost island of the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Known as "The Queen of the Hebrides", it lies in Argyll and Bute just south west of Jura and around 40 kilometres (22 nautical miles) north of the Northern Irish coast. The island's capital is Bowmore where the distinctive round Kilarrow Parish Church and a distillery are located. Port Ellen is the main port.

Islay is the fifth-largest Scottish island and the eighth-largest island of the British Isles, with a total area of almost 620 square kilometres (240 sq mi). There is ample evidence of the prehistoric settlement of Islay and the first written reference may have come in the first century AD. The island had become part of the Gaelic Kingdom of Dál Riata during the Early Middle Ages before being absorbed into the Norse Kingdom of the Isles.

The later medieval period marked a "cultural high point" with the transfer of the Hebrides to the Kingdom of Scotland and the emergence of the Clan Donald Lordship of the Isles, originally centred at Finlaggan. During the 17th century the power of Clan Donald waned, but improvements to agriculture and transport led to a rising population, which peaked in the mid-19th century. This was followed by substantial forced displacements and declining resident numbers.

Today, Islay has over 3,000 inhabitants, and the main commercial activities are agriculture, malt whisky distillation and tourism. The island has a long history of religious observance, and Scottish Gaelic is spoken by about a quarter of the population. Its landscapes have been celebrated through various art forms, and there is a growing interest in renewable energy in the form of wave power. Islay is home to many bird species such as the wintering populations of Greenland white-fronted and barnacle goose, and is a popular destination throughout the year for birdwatchers. The climate is mild and ameliorated by the Gulf Stream.Selected articles 73

The Schiehallion experiment was an 18th-century experiment to determine the mean density of the Earth. Funded by a grant from the Royal Society, it was conducted in the summer of 1774 around the Scottish mountain of Schiehallion, Perthshire. The experiment involved measuring the tiny deflection of the vertical due to the gravitational attraction of a nearby mountain. Schiehallion was considered the ideal location after a search for candidate mountains, thanks to its isolation and almost symmetrical shape. The experiment had previously been considered, but rejected, by Isaac Newton as a practical demonstration of his theory of gravitation; however, a team of scientists, notably Nevil Maskelyne, the Astronomer Royal, was convinced that the effect would be detectable and undertook to conduct the experiment. The deflection angle depended on the relative densities and volumes of the Earth and the mountain: if the density and volume of Schiehallion could be ascertained, then so could the density of the Earth. Once this was known, it would in turn yield approximate values for those of the other planets, their moons, and the Sun, previously known only in terms of their relative ratios.

A pendulum hangs straight downwards in a symmetrical gravitational field. However, if a sufficiently large mass such as a mountain is nearby, its gravitational attraction should pull the pendulum's plumb-bob slightly out of true (in the sense that it does not point to the centre of mass of the Earth). The change in plumb-line angle against a known object—such as a star—could be carefully measured on opposite sides of the mountain. If the mass of the mountain could be independently established from a determination of its volume and an estimate of the mean density of its rocks, then these values could be extrapolated to provide the mean density of the Earth, and by extension, its mass.

Selected articles 74

Craigmillar Castle is a ruined medieval castle in Edinburgh, Scotland. It is three miles (4.8 km) south-east of the city centre, on a low hill to the south of the modern suburb of Craigmillar. The Preston family of Craigmillar, the local feudal barons, began building the castle in the late 14th century and building works continued through the 15th and 16th centuries. In 1660, the castle was sold to Sir John Gilmour, Lord President of the Court of Session, who breathed new life into the ageing castle. The Gilmours left Craigmillar in the 18th century for a more modern residence, nearby Inch House, and the castle fell into ruin. It is now in the care of Historic Environment Scotland as a scheduled monument, and is open to the public.

Craigmillar Castle is best known for its association with Mary, Queen of Scots. Following an illness after the birth of her son, the future James VI, Mary arrived at Craigmillar on 20 November 1566 to convalesce. Before she left on 7 December 1566, a pact known as the "Craigmillar Bond" was made, with or without her knowledge, to dispose of her husband Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley.

Craigmillar is one of the best-preserved medieval castles in Scotland. The central tower house, or keep, is surrounded by a 15th-century courtyard wall with "particularly fine" defensive features. Within this are additional ranges, and the whole is enclosed by an outer courtyard wall containing a chapel and a doocot (dovecote).

Selected articles 75

The Isle of Arran (/ˈærən/; Scottish Gaelic: Eilean Arainn) or simply Arran is an island off the west coast of Scotland. It is the largest island in the Firth of Clyde and the seventh-largest Scottish island, at 432 square kilometres (167 sq mi). Historically part of Buteshire, it is in the unitary council area of North Ayrshire. In the 2022 census it had a resident population of 4,618. Though culturally and physically similar to the Hebrides, it is separated from them by the Kintyre peninsula. Often referred to as "Scotland in Miniature", the Island is divided into highland and lowland areas by the Highland Boundary Fault and has been described as a "geologist's paradise".

Arran has been continuously inhabited since the early Neolithic period. Numerous prehistoric remains have been found. From the 6th century onwards, Goidelic-speaking peoples from Ireland colonised it and it became a centre of religious activity. In the troubled Viking Age, Arran became the property of the Norwegian crown, until formally absorbed by the kingdom of Scotland in the 13th century. The 19th-century "clearances" led to significant depopulation and the end of the Gaelic language and way of life. The economy and population have recovered in recent years, the main industry being tourism. However, the increase in tourism and people buying holiday homes on the Island, the second highest rate of such homes in the UK, has led to a shortage of affordable homes on the Island. There is a diversity of wildlife, including three species of tree endemic to the area.

The Island includes miles of coastal pathways, numerous hills and mountains, forested areas, rivers, small lochs and beaches. Its main beaches are at Brodick, Whiting Bay, Kildonan, Sannox and Blackwaterfoot.Selected articles 76

Loch Lomond (/ˈlɒx ˈloʊmənd/; Scottish Gaelic: Loch Laomainn) is a freshwater Scottish loch which crosses the Highland Boundary Fault (HBF), often considered the boundary between the lowlands of Central Scotland and the Highlands. Traditionally forming part of the boundary between the counties of Stirlingshire and Dunbartonshire, Loch Lomond is split between the council areas of Stirling, Argyll and Bute and West Dunbartonshire. Its southern shores are about 23 kilometres (14 mi) northwest of the centre of Glasgow, Scotland's largest city. The Loch forms part of the Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park which was established in 2002. From a limnological perspective, Loch Lomond is classified as a dimictic lake, meaning it typically undergoes two mixing periods each year. This occurs in the spring and autumn when the water column becomes uniformly mixed due to temperature-driven density changes

Loch Lomond is 36.4 kilometres (22.6 mi) long and between one and eight kilometres (1⁄2–5 miles) wide, with a surface area of 71 km2 (27.5 sq mi). It is the largest lake in Great Britain by surface area; in the United Kingdom, it is surpassed only by Lough Neagh and Lough Erne in Northern Ireland. In the British Isles as a whole there are several larger loughs in the Republic of Ireland. The loch has a maximum depth of about 190 metres (620 ft) in the deeper northern portion, although the southern part of the loch rarely exceeds 30 metres (98 ft) in depth. The total volume of Loch Lomond is 2.6 km3 (0.62 cu mi), making it the second largest lake in Great Britain, after Loch Ness, by water volume.Due to its considerable depth and latitudinal location, Loch Lomond exhibits thermal stratification during the summer months, with a distinct epilimnion, metalimnion, and hypolimnion forming in deeper areas. These stratification patterns have important implications for nutrient cycling and aquatic ecology within the loch. During periods of stratification, a decrease in hypolimnetic oxygen can occur in the deeper northern basin, which can affect the species distribution patterns.Selected articles 77

Arbroath (/ɑːrˈbroʊθ/) or Aberbrothock (Scottish Gaelic: Obar Bhrothaig [ˈopəɾ ˈvɾo.ɪkʲ]) is a former royal burgh and the largest town in the council area of Angus, Scotland, with a population of 23,902. It lies on the North Sea coast, some 16 miles (26 km) east-northeast of Dundee and 45 miles (72 km) south-southwest of Aberdeen.

There is evidence of Iron Age settlement, but its history as a town began with the founding of Arbroath Abbey in 1178. It grew much during the Industrial Revolution through the flax and then the jute industry and the engineering sector. A new harbour was created in 1839; by the 20th century, Arbroath was one of Scotland's larger fishing ports.

The town is notable for the Declaration of Arbroath and the Arbroath smokie. Arbroath Football Club holds the world record for the number of goals scored in a professional football match: 36–0 against Bon Accord of Aberdeen in the Scottish Cup in 1885.The area of Arbroath has been inhabited since at least the Neolithic period. Material from postholes at an enclosure at Douglasmuir, near Friockheim, some five miles north of Arbroath, have been radiocarbon dated to about 3500 BCE. The function of the enclosure is unknown – perhaps for agriculture or for ceremonial purposes.

Bronze Age finds are abundant in the area. They include short-cist burials near West Newbigging, about a mile north of the town, which yielded pottery urns, a pair of silver discs and a gold armlet. Iron Age archaeology is also present, for example in the souterrain near Warddykes Cemetery and at West Grange of Conan, as well as better-known examples at Carlungie and Ardestie.

Selected articles 78

Carnoustie (/kɑːrˈnuːsti/; Scottish Gaelic: Càrn Ùstaidh) is a town and former police burgh in the council area of Angus, Scotland. It is at the mouth of the Barry Burn on the North Sea coast. In the 2011 census, Carnoustie had a population of 11,394, making it the fourth-largest town in Angus. The town was founded in the late 18th century, and grew rapidly throughout the 19th century due to the growth of the local textile industry. It was popular as a tourist resort from the early Victorian era up to the latter half of the 20th century, due to its seaside location, and is best known for the Carnoustie Golf Links course that often hosts the Open Championship.

Carnoustie can be considered a dormitory town for its nearest city, Dundee, which is 11 miles (18 kilometres) to the west. It is served principally by Carnoustie railway station, and also by Golf Street railway station. Its nearest major road is the A92, north of the town.Carnoustie benefited from the 19th-century fashion for sea bathing. The arrival of the railway enabled the town to develop as a popular tourist destination; it was promoted as the "Brighton of the North" in the early 20th century.

While golf has been played on Barry links since the 16th century, a formal 10 hole golf course was laid out in 1850 to the design of Alan Robertson of St Andrews. This was later improved in 1867 by Old Tom Morris, who added a further 8 holes. This course was redesigned in the 1920s by James Braid. In 1891, Arthur George Maule Ramsey, 14th Earl of Dalhousie, sold the links to the town on condition that they would be maintained for all time as a golf course. A three-day bazaar was held at the Kinnaird Hall in Dundee, which raised the funds for the purchase and secured the future of the links for golfing and leisure.

Selected articles 79

St Andrews Castle is a ruin located in the coastal Royal Burgh of St Andrews in Fife, Scotland. The castle sits on a rocky promontory overlooking a small beach called Castle Sands and the adjoining North Sea. There has been a castle standing at the site since the times of Bishop Roger (1189–1202), son of the Earl of Leicester. It housed the burgh’s wealthy and powerful bishops while St Andrews served as the ecclesiastical centre of Scotland during the years before the Protestant Reformation. In their Latin charters, the Archbishops of St Andrews wrote of the castle as their palace, signing, "apud Palatium nostrum."

The castle's grounds are now maintained by Historic Environment Scotland as a scheduled monument. The site is entered through a visitor centre with displays on its history. Some of the best surviving carved fragments from the castle are displayed in the centre, which also has a shop.During the Wars of Scottish Independence, the castle was destroyed and rebuilt several times as it changed hands between the Scots and the English. Soon after the sack of Berwick in 1296 by Edward I of England, the castle was taken and made ready for the English king in 1303. In 1314, however, after the Scottish victory at Bannockburn, the castle was retaken and repaired by Bishop William Lamberton, Guardian of Scotland, a loyal supporter of King Robert the Bruce. The English had recaptured it again by the 1330s and reinforced its defences in 1336, but were not successful in holding the castle. Sir Andrew Moray, Regent of Scotland in the absence of David II, recaptured it after a siege lasting three weeks. Shortly after this, in 1336–1337, it was destroyed by the Scots to prevent the English from once again using it as a stronghold.

Selected articles 80

A kilt (Scottish Gaelic: fèileadh [ˈfeːləɣ]) is a garment resembling a wrap-around knee-length skirt, made of twill-woven worsted wool with heavy pleats at the sides and back and traditionally a tartan pattern. Originating in the Scottish Highland dress for men, it is first recorded in the 16th century as the great kilt, a full-length garment whose upper half could be worn as a cloak. The small kilt or modern kilt emerged in the 18th century, and is essentially the bottom half of the great kilt. Since the 19th century, it has become associated with the wider culture of Scotland, and more broadly with Gaelic or Celtic heritage.

Although the kilt is most often worn by men on formal occasions and at Highland games and other sporting events, it has also been adapted as an item of informal male clothing, returning to its roots as an everyday garment. Kilts are now made for casual wear in a variety of materials. Alternative fastenings may be used and pockets inserted to avoid the need for a sporran. Kilts have also been adopted as female wear for some sports.The kilt first appeared as the great kilt, the breacan or belted plaid, during the 16th century. The filleadh mòr or great kilt was a full-length garment whose upper half could be worn as a cloak draped over the shoulder, or brought up over the head. A version of the filleadh beag (philibeg), or small kilt (also known as the walking kilt), similar to the modern kilt was invented by an English Quaker from Lancashire named Thomas Rawlinson some time in the 1720s. He felt that the belted plaid was "cumbrous and unwieldy", and his solution was to separate the skirt and convert it into a distinct garment with pleats already sewn, which he himself began making. His associate, Iain MacDonnell, chief of the MacDonnells of Inverness, also began making it, and when clansmen employed in logging, charcoal manufacture and iron smelting saw their chief making the new apparel, they soon followed making the kilt. From there its making use spread "in the shortest space" amongst the Highlanders, and even amongst some of the Northern Lowlanders. It has been suggested there is evidence that the philibeg with unsewn pleats was made from the 1690s. The kilt's design continued to evolve over the centuries, adapting to practical needs.

Selected articles 81

The Scottish Renaissance (Scottish Gaelic: Ath-bheòthachadh na h-Alba; Scots: Scots Renaissance) was a mainly literary movement of the early to mid-20th century that can be seen as the Scottish version of modernism. It is sometimes referred to as the Scottish literary renaissance, although its influence went beyond literature into music, visual arts, and politics (among other fields). key figures, like Hugh MacDiarmid, Sorley MacLean and other writers and artists of the Scottish Renaissance displayed a profound interest in both modern philosophy and technology, as well as incorporating folk influences, and a strong concern for the fate of Scotland's declining languages.

It has been seen as a parallel to other movements elsewhere, including the Irish Literary Revival, the Harlem Renaissance (in the USA), the Bengal Renaissance (in Kolkata, India) and the Jindyworobak Movement (in Australia), which emphasised indigenous folk traditions.The term "Scottish Renaissance" was brought into critical prominence by the French Languedoc poet and scholar Denis Saurat in his article "Le Groupe de la Renaissance Écossaise", which was published in the Revue Anglo-Américaine in April 1924. The term had appeared much earlier, however, in the work of the polymathic Patrick Geddes and in a 1922 book review by Christopher Murray Grieve ("Hugh MacDiarmid") for the Scottish Chapbook that predicted a "Scottish Renascence as swift and irresistible as was the Belgian Revival between 1880 and 1910", involving such figures as Lewis Spence and Marion Angus.

These earlier references make clear the connections between the Scottish Renaissance and the Celtic Twilight and Celtic Revival movements of the late 19th century, which helped reawaken a spirit of cultural nationalism among Scots of the modernist generations. Where these earlier movements had been steeped in a sentimental and nostalgic Celticism, however, the modernist-influenced Renaissance would seek a rebirth of Scottish national culture that would both look back to the medieval "makar" poets, William Dunbar and Robert Henryson, as well as look towards such contemporary influences as T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and D. H. Lawrence, or (more locally) R. B. Cunninghame Graham.

Selected articles 82

The University of St Andrews (Scots: University o St Andras, Scottish Gaelic: Oilthigh Chill Rìmhinn; abbreviated as St And in post-nominals) is a public university in St Andrews, Scotland. It is the oldest of the four ancient universities of Scotland and, following the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, the third-oldest university in the English-speaking world. St Andrews was founded in 1413 when the Avignon Antipope Benedict XIII issued a papal bull to a small founding group of Augustinian clergy. Along with the universities of Glasgow, Aberdeen, and Edinburgh, St Andrews was part of the Scottish Enlightenment during the 18th century.

St Andrews is made up of a variety of institutions, comprising three colleges — United College (a union of St Salvator's and St Leonard's Colleges), St Mary's College, and St Leonard's College, the last named being a non-statutory revival of St Leonard's as a post-graduate society. There are 18 academic schools organised into four faculties. The university spans both historic and contemporary buildings scattered across the town. The academic year is divided into two semesters, Martinmas and Candlemas. In term time, over one-third of the town's population are either staff members or students of the university. The student body is known for preserving ancient traditions such as Raisin Weekend, May Dip, and the wearing of distinctive academic dress.

The student body is also notably diverse: over 145 nationalities are represented with about 47% of its intake from countries outside the UK; a tenth of students are from Europe with the remainder from the rest of the world—20% from North America alone. Undergraduate admissions are now among the most selective in the country, with the university having the third-lowest offer rate for 2022 entry (behind only Oxford and Cambridge) and the highest entry standards of new students, as measured by UCAS entry tariff, at 215 points.

Selected articles 83

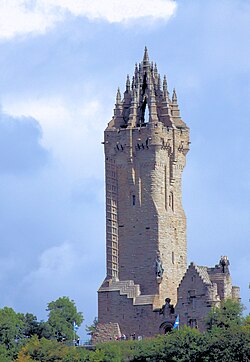

The National Wallace Monument (generally known as the Wallace Monument) is a 67 m (220 ft) tower on the shoulder of the Abbey Craig, a hilltop overlooking Stirling in Scotland. It commemorates Sir William Wallace, a 13th- and 14th-century Scottish hero.

The tower is open to the public for an admission fee. Visitors approach by foot from the base of the crag on which it stands. On entry there are 246 steps to the final observation platform, with three exhibition rooms within the body of the tower. The tower is not accessible to disabled visitors.The tower was constructed following a fundraising campaign, which accompanied a resurgence of Scottish national identity in the 19th century. The campaign was begun in Glasgow in 1851 by Rev Charles Rogers, who was joined by William Burns. Burns took sole charge from around 1855 following Rogers' resignation. In addition to public subscription, it was partially funded by contributions from a number of foreign donors, including Italian national leader Giuseppe Garibaldi. The Victorian Gothic monument was created by architect John Thomas Rochead.

The foundation stone was laid in 1861 by the Duke of Atholl in his role as Grand Master Mason of Scotland, with a short speech given by Sir Archibald Alison. Abbey Craig, a volcanic crag above Cambuskenneth Abbey, was chosen as the location of the tower, said to have been the point from which Wallace watched the gathering of the army of King Edward I of England just before the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297.

The sandstone tower, which is 67-metre (220-foot) tall, took eight years to build. It was completed in 1869 and cost £18,000 (about £1.8million in 2024).

The monument is open to the general public. Visitors climb the 246-step spiral staircase to the viewing gallery inside the monument's crown, which provides expansive views of the Ochil Hills and the Forth Valley.

Selected articles 84

The Royal Banner of the Royal Arms of Scotland, also known as the Royal Banner of Scotland, or more commonly the Lion Rampant of Scotland, and historically as the Royal Standard of Scotland, (Scottish Gaelic: Bratach rìoghail na h-Alba, Scots: Ryal banner o Scotland) or Banner of the King of Scots, is the royal banner of Scotland, and historically, the royal standard of the Kingdom of Scotland. Used historically by the Scottish monarchs, the banner differs from Scotland's national flag, the Saltire, in that its official use is restricted by an Act of the Parliament of Scotland to only a few Great Officers of State who officially represent the Monarchy in Scotland. It is also used in an official capacity at royal residences in Scotland when the Head of State is not present.

The earliest recorded use of the Lion Rampant as a royal emblem in Scotland was by Alexander II in 1222; with the additional embellishment of a double border set with lilies occurring during the reign of Alexander III (1249–1286). This emblem occupied the shield of the royal coat of arms of the ancient Kingdom of Scotland which, together with a royal banner displaying the same, was used by the King of Scots until the Union of the Crowns in 1603, when James VI acceded to the thrones of the kingdoms of England and Ireland. Since 1603, the lion rampant of Scotland has been incorporated into both the royal arms and royal banners of successive Scottish then British monarchs in order to symbolise Scotland, as can be seen today in the Royal Standard of the United Kingdom. Although now officially restricted to use by representatives of the Monarch and at royal residences, the Royal Banner continues to be one of Scotland's most recognisable symbols.Selected articles 85

RMS Queen Mary is a retired British ocean liner that operated primarily on the North Atlantic Ocean from 1936 to 1967 for the Cunard Line. It is currently a hotel, museum, and convention space in Long Beach, California, United States. It is on the US National Register of Historic Places and member of Historic Hotels of America, the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Built by John Brown & Company in Clydebank, Scotland, she was subsequently joined by RMS Queen Elizabeth in Cunard's two-ship weekly express service between Southampton, Cherbourg and New York. These "Queens" were the British response to the express superliners built by German, Italian, and French companies in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Queen Mary sailed on her maiden voyage on 27 May 1936 and won the Blue Riband that August; she lost the title to SS Normandie in 1937 and recaptured it in 1938, holding it until 1952, when the new SS United States claimed it. With the outbreak of World War II, she was converted into a troopship and ferried Allied soldiers during the conflict. On one voyage in 1943, she carried over 16,600 people, still the record for the most people on one vessel at the same time.

Following the war, Queen Mary returned to passenger service and, along with Queen Elizabeth, commenced the two-ship transatlantic passenger service for which the two ships were initially built. The pair dominated the transatlantic passenger transportation market until the dawn of the jet age in the late 1950s. By the mid-1960s, Queen Mary was ageing and operating at a loss.

Selected articles 86

The Kingdom of Scotland was a sovereign state in northwest Europe, traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a land border to the south with the Kingdom of England. During the Middle Ages, Scotland engaged in intermittent conflict with England, most prominently the Wars of Scottish Independence, which saw the Scots assert their independence from the English. Following the annexation of the Hebrides and the Northern Isles from Norway in 1266 and 1472 respectively, and the capture of Berwick by England in 1482, the territory of the Kingdom of Scotland corresponded to that of modern-day Scotland, bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the southwest.

In 1603, James VI of Scotland became King of England, joining Scotland with England in a personal union. In 1707, during the reign of Queen Anne, the two kingdoms were united to form the Kingdom of Great Britain under the terms of the Acts of Union. The Crown was the most important element of Scotland's government. The Scottish monarchy in the Middle Ages was a largely itinerant institution, before Edinburgh developed as a capital city in the second half of the 15th century. The Crown remained at the centre of political life and in the 16th century emerged as a major centre of display and artistic patronage, until it was effectively dissolved with the 1603 Union of Crowns. The Scottish Crown adopted the conventional offices of western European monarchical states of the time and developed a Privy Council and great offices of state. Parliament also emerged as a major legal institution, gaining an oversight of taxation and policy, but was never as central to the national life. In the early period, the kings of the Scots depended on the great lords—the mormaers and toísechs—but from the reign of David I, sheriffdoms were introduced, which allowed more direct control and gradually limited the power of the major lordships.

In the 17th century, the creation of Justices of Peace and Commissioners of Supply helped to increase the effectiveness of local government. The continued existence of courts baron and the introduction of kirk sessions helped consolidate the power of local lairds. Scots law developed in the Middle Ages and was reformed and codified in the 16th and 17th centuries. Under James IV the legal functions of the council were rationalised, with Court of Session meeting daily in Edinburgh. In 1532, the College of Justice was founded, leading to the training and professionalisation of lawyers. David I is the first Scottish king known to have produced his own coinage. After the union of the Scottish and English crowns in 1603, the Pound Scots was reformed to closely match sterling coin. The Bank of Scotland issued pound notes from 1704. Scottish currency was abolished by the Acts of Union 1707; however, Scotland has retained unique banknotes to the present day.Selected articles 87

The Edinburgh Festival Fringe (also referred to as the Edinburgh Fringe, the Fringe or the Edinburgh Fringe Festival) is the world's largest performance arts festival, which in 2024 spanned 25 days, sold more than 2.6 million tickets and featured more than 51,446 scheduled performances of 3,746 different shows across 262 venues from 60 different countries. Of those shows, the largest section was comedy, representing almost 40% of shows, followed by theatre, which was 26.6% of shows.

Established in 1947 as an unofficial offshoot to (and on the "fringe" of) the Edinburgh International Festival, it takes place in Edinburgh every August. The combination of Edinburgh Festival Fringe and Edinburgh International Festival has become a world-leading celebration of arts and culture, surpassed only by the Olympics and the World Cup in terms of global ticketed events.

It is an open-access (or "unjuried") performing arts festival, meaning that there is no selection committee, and anyone may participate, with any type of performance. The official Fringe Programme categorises shows into sections for theatre, comedy, dance, physical theatre, circus, cabaret, children's shows, musicals, opera, music, spoken word, exhibitions, and events. Comedy is the largest section, making up over one-third of the programme, and the one that in modern times has the highest public profile, due in part to the Edinburgh Comedy Awards.

Selected articles 88

The University of Glasgow (abbreviated as Glas. in post-nominals; Scottish Gaelic: Oilthigh Ghlaschu) is a public research university in Glasgow, Scotland. Founded by papal bull in 1451 [O.S. 1450], it is the fourth-oldest university in the English-speaking world and one of Scotland's four ancient universities. Along with the universities of St Andrews, Aberdeen, and Edinburgh, the university was part of the Scottish Enlightenment during the 18th century. Glasgow is the second largest university in Scotland by total enrolment and 9th-largest in the United Kingdom.

In common with universities of the pre-modern era, Glasgow originally educated students primarily from wealthy backgrounds; however, it became a pioneer in British higher education in the 19th century by also providing for the needs of students from the growing urban and commercial middle class. Glasgow University served all of these students by preparing them for professions: law, medicine, civil service, teaching, and the church. It also trained smaller but growing numbers for careers in science and engineering. Glasgow has the fifth-largest endowment of any university in the UK and the annual income of the institution for 2023–24 was £950 million of which £221.1 million was from research grants and contracts, with an expenditure of £658.6 million. It is a member of Universitas 21, the Russell Group and the Guild of European Research-Intensive Universities.

The university was originally located in the city's High Street; since 1870, its main campus has been at Gilmorehill in the City's West End. Additionally, a number of university buildings are located elsewhere, such as the Veterinary School in Bearsden, and the Crichton Campus in Dumfries.

The alumni of the University of Glasgow include some of the major figures of modern history, including James Wilson, a signatory of the United States Declaration of Independence, 3 Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom (William Lamb, Henry Campbell-Bannerman and Bonar Law), 3 Scottish First Ministers (Humza Yousaf, Nicola Sturgeon and Donald Dewar), economist Adam Smith, philosopher Francis Hutcheson, engineer James Watt, physicist Lord Kelvin, surgeon Joseph Lister along with 4 Nobel Prize laureates (in total 8 Nobel Prize winners are affiliated with the University) and numerous Olympic gold medallists, including the current chancellor, Dame Katherine Grainger.Selected articles 89

The Encyclopædia Britannica (Latin for 'British Encyclopaedia') is a general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, which spans 32 volumes and 32,640 pages, was the last printed edition. Since 2016, it has been published exclusively as an online encyclopaedia at the website Britannica.com

Printed for 244 years, the Britannica was the longest-running in-print encyclopaedia in the English language. It was first published between 1768 and 1771 in Edinburgh, Scotland, in three volumes. The encyclopaedia grew in size; the second edition was 10 volumes, and by its fourth edition (1801–1810), it had expanded to 20 volumes. Its rising stature as a scholarly work helped recruit eminent contributors, and the 9th (1875–1889) and 11th editions (1911) are landmark encyclopaedias for scholarship and literary style. Starting with the 11th edition and following its acquisition by an American firm, the Britannica shortened and simplified articles to broaden its appeal to the North American market.

In 1933, the Britannica became the first encyclopaedia to adopt "continuous revision", in which the encyclopaedia is continually reprinted, with every article updated on a schedule. In the 21st century, the Britannica suffered first from competition with the digital multimedia encyclopaedia Microsoft Encarta, and later with the online peer-produced encyclopaedia Wikipedia.

In March 2012, it announced it would no longer publish printed editions and would focus instead on the online version.

Selected articles 90

The Commando Memorial is a Category A listed monument in Lochaber, Scotland, dedicated to the men of the original British Commando Forces raised during World War II. Situated around a mile from Spean Bridge, it overlooks the training areas of the Commando Training Depot established in 1942 at Achnacarry Castle. Unveiled in 1952 by the Queen Mother, it is one of Scotland's best-known monuments, both as a war memorial and as a tourist attraction offering views of Ben Nevis and Aonach Mòr.

In 1949, the sculptor Scott Sutherland won a competition open to all Scottish sculptors for the commission, The Commando Memorial. Sutherland's design won first prize of £200. The base of the bronze statue is inscribed with the date of 1951. The sculpture was cast by H.H. Martyn & Co. The memorial was officially unveiled by the Queen Mother on 27 September 1952. The monument was first designated as a listed structure on 5 October 1971, and was upgraded to a Category A listing on 15 August 1996. On 18 November 1993 a further plaque was added to mark the Freedom of Lochaber being given to the Commando Association. On 27 March 2010 a two-mile (three-kilometre) war memorial path was opened connecting two local war memorials, the Commando Memorial, and the former High Bridge built by General Wade, where the first shots were fired in the Jacobite Rising of 1745 in the Highbridge Skirmish.

The monument consists of a cast bronze sculpture of three Commandos in characteristic dress complete with cap comforter, webbing and rifle, standing atop a stone plinth looking south towards Ben Nevis. The soldier at the front is thought to depict Commando Jack Lewington who frequently attended Remembrance Services at the monument during his lifetime. One of the other two soldiers is Frank Nicholls (rank unknown) the other is Regimental Sergeant Major Sidney Hewlett. Originally serving with the Welsh Guards, he was hand picked to be one of the founding NCOs of the commandos, and was also held in high regard and noted several times by Eisenhower. The entire monument is 17 feet (5.2 metres) tall. The monument has been variously described as a huge, striking and iconic statue.

Selected articles 91

The Church of Scotland (CoS; Scots: The Kirk o Scotland; Scottish Gaelic: Eaglais na h-Alba) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While membership in the church has declined significantly in recent decades (in 1982 it had nearly 920,000 members), the government Scottish Household Survey concluded that 20% of the Scottish population, or over one million people, identified the Church of Scotland as their religious identity in 2019.

In the 2022 census, 20.4% of the Scottish population, or 1,108,796 adherents, identified the Church of Scotland as their religious identity. The Church of Scotland's governing system is presbyterian in its approach; therefore, no one individual or group within the church has more or less influence over church matters. There is no one person who acts as the head of faith, as the church believes that role is the "Lord God's". As a proper noun, the Kirk is an informal name for the Church of Scotland used in the media and by the church itself.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox in the Reformation of 1560 when it split from the Catholic Church and established itself as a church in the Reformed tradition. The Presbyterian tradition in ecclesiology (form of the church government) believe that God invited the church's adherents to worship Jesus, with church elders collectively answerable for correct practice and discipline.

The Church of Scotland celebrates two sacraments, Baptism and the Lord's Supper, as well as five other ordinances, such as Confirmation and Matrimony. The church adheres to the Bible and the Westminster Confession of Faith and is a member of the World Communion of Reformed Churches. The annual meeting of the church's general assembly is chaired by the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.Selected articles 92

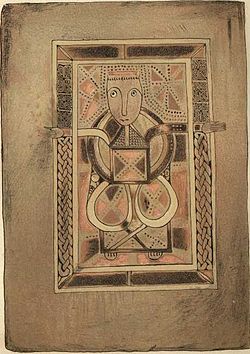

The Book of Deer (Scottish Gaelic: Leabhar Dhèir) (Cambridge University Library, MS. Ii.6.32) is a 10th-century Latin Gospel Book with early 12th-century additions in Latin, Old Irish and Scottish Gaelic. It contains the earliest surviving Gaelic writing from Scotland.

The origin of the book is uncertain, but it is reasonable to assume that the manuscript was at Deer, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, when the marginalia were made. It may be the oldest surviving manuscript produced in Scotland (although see Book of Kells), and is notable for having possibly originated in what is now considered a Lowland area. The manuscript belongs to the category of Irish pocket gospel books, which were produced for private use rather than for church services. While the manuscripts to which the Book of Deer is closest in character are all Irish, most scholars argue for a Scottish origin, although the book was undoubtedly written by an Irish scribe. The book has 86 folios; the leaves measure 157 mm by 108 mm, the text area 108 mm by 71 mm. It is written on vellum in brown ink and is in a modern binding.

The Book of Deer has been in the ownership of the Cambridge University Library since 1715, when the library of John Moore, Bishop of Ely, was presented to the University of Cambridge by King George I.The Latin text contains the complete text of the Gospel of John, portions of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, a portion of an Office for the Visitation of the Sick, and the Apostles' Creed. It ends with a colophon in Old Irish. The Gospel texts are based on the Vulgate but contain some peculiarities unique to Irish Gospel books. The texts are written in an Irish minuscule text, apparently by a single scribe. Although the text and the script of the manuscript place it squarely in the tradition of the Irish pocket gospel, scholars have argued that the manuscript was produced in Scotland.

Selected articles 93

Tantallon Castle is a ruined mid-14th-century fortress, located 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) east of North Berwick, in East Lothian, Scotland. It sits atop a promontory opposite the Bass Rock, looking out onto the Firth of Forth. The last medieval curtain wall castle to be constructed in Scotland, Tantallon comprises a single wall blocking off the headland, with the other three sides naturally protected by sea cliffs.

Tantallon was built in the mid 14th century by William Douglas, 1st Earl of Douglas. It was passed to his illegitimate son, George Douglas, later created Earl of Angus, and despite several sieges, it remained the property of his descendants for much of its history. It was besieged by King James IV in 1491, and again by his successor James V in 1527, when extensive damage was done. Tantallon saw action in the First Bishops' War in 1639, and again during Oliver Cromwell's invasion of Scotland in 1651, when it was once more severely damaged. It was sold by the Marquis of Douglas in 1699 to Hew Dalrymple, Lord North Berwick and the ruin is today in the care of Historic Environment Scotland.Tantallon is a unique construction within Scotland, the defences comprising only a single large wall securing a coastal promontory. The south-east, north-east, and north-west approaches are naturally defended by steep sea cliffs and were only ever protected by relatively small defensive walls. To the southwest, a massive curtain wall blocks off the end of the promontory, which forms the inner courtyard. The curtain wall is built of the local red sandstone and has a tower at each end and a heavily fortified gatehouse in the centre, all of which provided residential accommodation. A north range of buildings, containing a hall, completed the main part of the castle, enclosing a courtyard around 70 by 44 metres (230 by 144 ft). In total, the buildings of the castle provided around 1,100 square metres (12,000 sq ft) of accommodation.

Selected articles 94

The Scottish Terrier (Scottish Gaelic: Abhag Albannach; also known as the Aberdeen Terrier), popularly called the Scottie, is a breed of dog. Initially one of the highland breeds of terrier that were grouped under the name of Skye Terrier, it is one of five breeds of terrier that originated in Scotland, the other four being the modern Skye, Cairn, Dandie Dinmont, and West Highland White terriers. They are an independent and rugged breed with a wiry outer coat and a soft dense undercoat. The first Earl of Dumbarton nicknamed the breed "the diehard". According to legend, the Earl of Dumbarton gave this nickname because of the Scottish Terriers' bravery, and Scotties were also the inspiration for the name of his regiment, The Royal Scots, Dumbarton's Diehard. Scottish Terriers were originally bred to hunt vermin on farms.

They are a small breed of terrier with a distinctive shape and have had many roles in popular culture. They have been owned by a variety of celebrities, including the 32nd president of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whose Scottie Fala is included with FDR in a statue in Washington, D.C., as well as by the 43rd president, George W. Bush. They are also well known for being a playing piece in the board game Monopoly. Described as territorial, feisty dogs, they can make a good watchdog and tend to be very loyal to their family. Healthwise, Scottish Terriers can be more prone to bleeding disorders, joint disorders, autoimmune diseases, allergies, and cancer than some other breeds of dog, and there is a condition named after the breed called Scotty cramp. They are also one of the more successful dog breeds at the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show with a best in show in 2010.Initial grouping of several of the highland terriers (including the Scottie) under the generic name Skye Terriers caused some confusion in the breed's lineage. There is disagreement over whether the Skye Terriers mentioned in early 16th century records actually descended from forerunners of the Scottie or vice versa. It is certain, however, that Scotties and West Highland White Terriers are closely related—both their forefathers originated from the Blackmount region of Perthshire and the Moor of Rannoch. Scotties were originally bred to hunt and kill vermin on farms and to hunt badgers and foxes in the Highlands of Scotland.

Selected articles 95

No. 4472 Flying Scotsman is a LNER Class A3 4-6-2 "Pacific" steam locomotive built in 1923 for the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) at Doncaster Works to a design of Nigel Gresley. It was employed on long-distance express passenger trains on the East Coast Main Line by LNER and its successors, British Railways' Eastern and North Eastern Regions, notably on The Flying Scotsman service between London King's Cross and Edinburgh Waverley after which it was named.

Retired from British Railways in 1963 after covering 2.08 million miles, Flying Scotsman has been described as the world's most famous steam locomotive. It had earned considerable fame in preservation under the ownership of, successively, Alan Pegler, William McAlpine, Tony Marchington, and, since 2004, the National Railway Museum. 4472 became a flagship locomotive for the LNER, representing the company twice at the British Empire Exhibition and in 1928, hauled the inaugural non-stop Flying Scotsman service. It set two world records for steam traction, becoming the first locomotive to reach the officially authenticated speed of 100 miles per hour (161 km/h) on 30 November 1934, and setting the longest non-stop run of a steam locomotive of 422 miles (679 km) on 8 August 1989 while on tour in Australia.In July 1922, the Great Northern Railway (GNR) filed Engine Order No. 297 which gave the green-light for ten Class A1 4-6-2 "Pacific" locomotives to be built at Doncaster Works. Designed by Nigel Gresley, the A1s were built to haul mainline and later express passenger trains and following the GNR's absorption into the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) after the amalgamation of 1923, became a standard design. Flying Scotsman cost £7,944 to build, and was the first engine delivered to the newly-formed LNER. It entered service on 24 February 1923, carrying the GNR number of 1472 as the LNER had not yet decided on a system-wide numbering scheme. In February 1924 the locomotive received its name after the LNER's Flying Scotsman express service between London King's Cross and Edinburgh Waverley, and was assigned a new number, 4472.

Selected articles 96

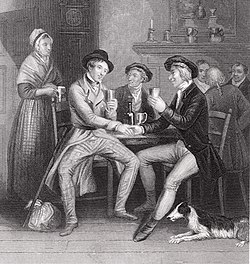

"Auld Lang Syne" (Scots pronunciation: [ˈɔːl(d) lɑŋ ˈsəi̯n]) is a Scottish song. In the English-speaking world, it is traditionally sung to bid farewell to the old year at the stroke of midnight on Hogmanay/New Year's Eve. It is also often heard at funerals, graduations, and as a farewell or ending to other occasions; for instance, many branches of the Scouting movement use it to close jamborees and other functions.

The text is a Scots-language poem written by Robert Burns in 1788 but based on an older Scottish folk song. In 1799, it was set to a traditional pentatonic tune, which has since become standard. "Auld Lang Syne" is listed as numbers 6294 and 13892 in the Roud Folk Song Index.

The poem's Scots title may be translated into standard English as "old long since" or, less literally, "long long ago", "days gone by", "times long past" or "old times". Consequently, "For auld lang syne", as it appears in the first line of the chorus, might be loosely translated as "for the sake of old times".

The phrase "Auld Lang Syne" is also used in similar poems by Robert Ayton (1570–1638), Allan Ramsay (1686–1757), and James Watson (1711), as well as older folk songs predating Burns.

In modern times, Matthew Fitt uses the phrase "in the days of auld lang syne" as the equivalent of "once upon a time" in his retelling of fairy tales in the Scots language.Selected articles 97

Scotland in the modern era, from the end of the Jacobite risings and beginnings of industrialisation in the 18th century to the present day, has played a major part in the economic, military and political history of the United Kingdom, British Empire and Europe, while recurring issues over the status of Scotland, its status and identity have dominated political debate.

Scotland made a major contribution to the intellectual life of Europe, particularly in the Enlightenment, producing major figures including the economist Adam Smith, philosophers Francis Hutcheson and David Hume, and scientists William Cullen, Joseph Black and James Hutton. In the 19th century major figures included James Watt, James Clerk Maxwell, Lord Kelvin and Sir Walter Scott. Scotland's economic contribution to the Empire and the Industrial Revolution included its banking system and the development of cotton, coal mining, shipbuilding and an extensive railway network. Industrialisation and changes to agriculture and society led to depopulation and clearances of the largely rural highlands, migration to the towns and mass emigration, where Scots made a major contribution to the development of countries including the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

In the 20th century, Scotland played a major role in the British and allied effort in the two world wars and began to suffer a sharp industrial decline, going through periods of considerable political instability. The decline was particularly acute in the second half of the 20th century, but was compensated for to a degree by the development of an extensive oil industry, technological manufacturing and a growing service sector. This period also increasing debates about the place of Scotland within the United Kingdom, the rise of the Scottish National Party and after a referendum in 1999 the establishment of a devolved Scottish Parliament.

Selected articles 98

The Glasgow Airport attack was a terrorist ramming attack which occurred on 30 June 2007, at 15:11 BST, when a dark green Jeep Cherokee loaded with propane canisters was driven at the glass doors of the Glasgow Airport terminal and set ablaze. The car's driver was severely burnt in the ensuing fire, and five members of the public were injured, none seriously. Some injuries were sustained by those assisting the police in detaining the occupants. A close link was quickly established to the 2007 London car bombs the previous day.

Both of the car's occupants were apprehended at the scene. Within three days, Scotland Yard had confirmed that eight people had been taken into custody in connection with this incident and that in London.

Police identified the two men as Bilal Abdullah, a British-born, Muslim doctor of Iraqi descent working at the Royal Alexandra Hospital, and Kafeel Ahmed, also known as Khalid Ahmed, an Indian-born engineer and the driver, who was treated for fatal burns at the same hospital. The newspaper The Australian alleged that a suicide note indicated that the two had intended to die in the attack. Kafeel Ahmed died from his injuries on 2 August. Bilal Abdullah was later found guilty of conspiracy to commit murder and was sentenced to life imprisonment with a minimum of 32 years.

The attack was the first terrorist incident to take place in Scotland since the Lockerbie bombing in 1988. It also took place three days after the appointment of Scottish MP Gordon Brown as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, but Downing Street dismissed suggestions of a connection.Selected articles 99

The Jacobite rising of 1745 was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took place during the War of the Austrian Succession, when the bulk of the British Army was fighting in mainland Europe, and proved to be the last in a series of revolts that began in March 1689, with major outbreaks in 1715 and 1719.

Charles launched the rebellion on 19 August 1745 at Glenfinnan in the Scottish Highlands, capturing Edinburgh and winning the Battle of Prestonpans in September. At a council in October, the Scots agreed to invade England after Charles assured them of substantial support from English Jacobites and a simultaneous French landing in Southern England. On that basis, the Jacobite army entered England in early November, but neither of these assurances proved accurate. On reaching Derby on 4 December, they halted to discuss future strategy.

Similar discussions had taken place at Carlisle, Preston, and Manchester and many felt they had gone too far already. The invasion route had been selected to cross areas considered strongly Jacobite in sympathy, but the promised English support failed to materialise. With several government armies marching on their position, they were outnumbered and in danger of being cut off. The decision to retreat was supported by the vast majority, but caused an irretrievable split between Charles and his Scots supporters. Despite victory at Falkirk Muir in January 1746, defeat at Culloden in April ended the rebellion. Charles escaped to France, but was unable to win support for another attempt, and died in Rome in 1788.

Selected articles 100

The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, Scotland, is a museum of Scottish history and culture.

It was formed in 2006 with the merger of the new Museum of Scotland, with collections relating to Scottish antiquities, culture and history, and the adjacent Royal Scottish Museum (opened in 1866 as the Edinburgh Museum of Science and Art, renamed in 1904, and for the period between 1985 and the merger named the Royal Museum of Scotland or simply the Royal Museum), with international collections covering science and technology, natural history, and world cultures. The two connected buildings stand beside each other on Chambers Street, by the junction with the George IV Bridge, in central Edinburgh. The museum is part of National Museums Scotland and admission is free.

The two buildings retain distinctive characters: the Museum of Scotland is housed in a modern building opened in 1998, while the former Royal Museum building was begun in 1861 and partially opened in 1866, with a Victorian Venetian Renaissance façade and a grand central hall of cast iron construction that rises the full height of the building, designed by Francis Fowke and Robert Matheson. This building underwent a major refurbishment and reopened on 29 July 2011 after a three-year, £47 million project to restore and extend the building led by Gareth Hoskins Architects along with the concurrent redesign of the exhibitions by Ralph Appelbaum Associates.

The National Museum incorporates the collections of the former National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland. As well as the national collections of Scottish archaeological finds and medieval objects, the museum contains artefacts from around the world, encompassing geology, archaeology, natural history, science, technology, art, and world cultures. The sixteen new galleries reopened in 2011 include 8,000 objects, 80% of which were not previously on display. One of the more notable exhibits is the stuffed body of Dolly the sheep, the first successful cloning of a mammal from an adult cell. Other highlights include Ancient Egyptian exhibitions, one of Sir Elton John's extravagant suits, the Jean Muir Collection of costume and a large kinetic sculpture named the Millennium Clock. A Scottish invention that is a perennial favourite with children visiting as part of school trips is the Scottish Maiden, an early beheading machine predating the French guillotine.Selected articles 101

The Acts of Union refer to two acts of Parliament, one by the Parliament of Scotland in March 1707, followed shortly thereafter by an equivalent act of the Parliament of England. They put into effect the international Treaty of Union agreed on 22 July 1706, which politically joined the Kingdom of England and Kingdom of Scotland into a single "political state" named Great Britain, with Queen Anne as its sovereign. The English and Scottish acts of ratification took effect on 1 May 1707, creating the new kingdom, with its parliament based in the Palace of Westminster.

The two countries had shared a monarch since the "personal" Union of the Crowns in 1603, when James VI of Scotland inherited the English throne from his cousin Elizabeth I to become (in addition) 'James I of England', styled James VI and I. Attempts had been made to try to unite the two separate countries, in 1606, 1667, and in 1689 (following the 1688 Dutch invasion of England, and subsequent deposition of James II of England by his daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange), but it was not until the early 18th century that both nations via separate groups of English and Scots Royal Commissioners and their respective political establishments, came to support the idea of an international "Treaty of political, monetary and trade Union", albeit for different reasons.Prior to 1603, England and Scotland had different monarchs, but when Elizabeth I died without children, she was succeeded as King of England by her distant relative, James VI of Scotland. After her death, the two Crowns were held in personal union by James (reigning as James VI and I), who announced his intention to unite the two realms.

The 1603 Union of England and Scotland Act established a joint Commission to agree terms, but the Parliament of England was concerned this would lead to an absolutist structure similar to that of Scotland. James was forced to withdraw his proposals, but used the royal prerogative to take the title "King of Great Britain".

Selected articles 102