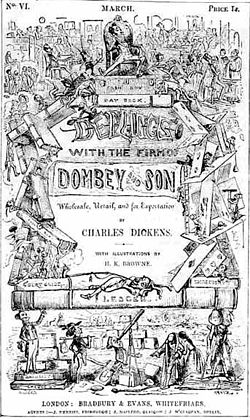

Vision of Contemporary England in Dombey and Son

Coverage of the monthly issues | |

| Author | Charles Dickens |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Published | 1995 |

| Publisher | Bradbury and Evans |

Publication date | 1848 |

| Publication place | |

| ISBN | 1-85326-257-9 |

Dombey and Son (1846–1848) by Charles Dickens was published during profound economic and social upheaval, political instability, and changes affecting every layer of society. The novel is not an exhaustive document on the condition of England, nor even of London, which plays a role within it; nor does it present itself as a “social” novel in the same way as Hard Times. However, while Dickens does perceive the forces at play—the emergence of new values, the dangers of a relentless pursuit of money, this Mammon of the modern age—his response remains deeply artistic.

It is difficult to separate what he condemns from what he admires: on one hand, the society represented by Dombey is lifeless; on the other, Solomon Gills’s shop, “The Wooden Midshipman,” a quasi-pastoral haven of peace and innocent happiness, is economically outdated and only saved from bankruptcy through the providential intervention of the very investments that are being critiqued.

The novel also devotes considerable attention to the condition of women, which it explores—often symbolically—through various aspects: family relationships, motherhood, and domestic virtues. Its ideal, frequently expressed in earlier novels, remains the “angel in the house” embodied by Florence, though some critics have questioned this framework and given more importance to the sexual dimension of femininity.

A changing environment

[edit]

As A. J. Cockshut writes, Dombey and Son, “perhaps the first major English novel to concern itself with industrial society […] stands apart from Dickens’s other works, and even more so from those of the time, in that it is steeped in the atmosphere of the decade it depicts—the 1840s, the age of railway mania.”[1]

It is, above all, a “London book,” with the city acting as the hub of economic development through the influence its power has acquired.[2] Dickens depicts the city’s sprawl as destructive to the human community, fostering isolation and separation; however, unlike Bleak House, for example, he does not dwell on the sordid aspects of the capital, the slum districts and bricklayers’ housing, the stench of cemeteries, etc.[3] Instead, he evokes various neighborhoods, each with its distinct atmosphere: Portland Place, where Mr. Dombey resides, imposes with its silence and sadness; Princess’s Place, home to Miss Tox and Major Bagstock, belongs to the shabby genteel, fallen, and impoverished but obsessed with the Regency lifestyle, a taste and refinement they can no longer afford. In stark contrast lies “The Wooden Midshipman,” a symbol of “Old England” (Olde England or Merry Olde England),[4] a still-vibrant utopia of pastoral and bucolic peace.[5] Then come the suburbs already familiar in Dickens’s work: Staggs’s Gardens, where the Toodles live and where Good Mrs. Brown lurks in her den, as well as Harriet Carker in her modest home.[3][4]

However, London has transformed into a modern Babylon where the unemployed poor flock, and as chapter 33 states, they “feed the hospitals, the cemeteries, the prisons, the river, the fevers, the madness, the vice and the death—all doomed, all in thrall to the distant roaring monster.”[6][7] Moreover, the urban landscape is being disrupted by railway construction to such an extent that Staggs’s Gardens, having suffered “the shock of an earthquake,” now resembles a large disjointed body, disemboweled and gaping open.[6] Yet, despite the mutilations it inflicts, the intrusion of the railway also symbolizes the arrival of a new civilization marked by wealth: proof of this is that Mr. Toodle, once a stoker—an unskilled laborer in charge of feeding the massive coal boiler—has been promoted to locomotive engineer.[7]

A shaken society

[edit]Like many of Dickens’s novels, Dombey and Son offers a panoramic view of urban society, but within it are signs of profound structural evolution.[7]

Decline of certain social classes

[edit]-

William Hogarth, Marriage à la mode (1743) 1. The contract.

-

Marriage à la mode 2. The tête-à-tête.

-

Marriage à la mode 3. The visit to the charlatan.

-

Marriage à la mode 4. The rising.

-

Marriage à la mode 5. The death of the count.

-

Marriage à la mode 6. The suicide.

Some traditional social classes appear to be in decline, particularly the small tradesmen like Solomon Gills or the new poor of the old order, most notably represented by Miss Tox.

The latter, despite a remnant of outward grandeur, lives in a “dingy tenement” with furnishings reminiscent of the “braids and powdered wigs” she nostalgically longs for—particularly a plate-warmer perched on four arched, wobbly legs, a dated harpsichord decorated with a garland of sweet peas, all steeped in a musty odor that clings to the visitor’s throat.[8] Miss Tox, scorned by Mr. Dombey and Mrs. Chick for her poverty, embodies a certain kind of aristocracy stubbornly fixated on the past—now ruined, yet constantly in pursuit of fortunate marriages.

Such is the case with Mrs. Skewton, who sells her daughter as if at an auction, Edith offering, in exchange for money, the dual privilege of birth and social status. This evokes practices already well established in the 18th century, as illustrated by William Hogarth’s famous six-painting series Marriage à la Mode.[7]

Likewise, Cousin Feenix (Lord Cousin Feenix), Edith Granger’s relative who takes her in after she flees the Dombey household, represents another grotesque figure of the aristocracy: the impoverished nobleman, unable to maintain his rank in the crumbling ancestral home, yet quick to sniff out a good deal. He rushes from Baden-Baden, exclaiming in Chapter 3: “When you’ve truly got a rich city chap in the family, you’ve got to show him some attention—let’s do something for him!”[9] This somewhat deranged cousin foreshadows the “idiot cousin” in Bleak House, the ultimate sign of the degeneration of a declining aristocracy.[10]

The rise of the moneyed bourgeoisie

[edit]The rise of the moneyed bourgeoisie of this period marks a departure from the merchants and shopkeepers of the 18th century, whose wealth was grounded in Puritan values such as thrift, hard work, and self-help—that is, reliance on one’s own efforts. In this context, a new form of capitalism emerges, exemplified by figures such as Mr. Dombey: enriched through speculation and investment, he enjoys a social status secured by his assets and displayed in the lavishness of his lifestyle, awaiting only the validation of an upper-class marriage. Carker the Manager similarly exhibits characteristics associated with this new class of businessmen: emotional coldness, strict self-control, and resolute ambition. Both characters place high value on material wealth and possess a strong sense of superiority, often viewing those they consider socially inferior—particularly members of the working class—with disdain.[10]

The latter—meaning the working class—is scarcely represented in the novel, all the more so as characters like the Toodles, Susan Nipper, Captain Cuttle, and Mrs. MacStinger do not truly represent social types, but rather fall into the category of so-called "humour characters," that is, figures defined by a single trait, most often comic or eccentric. Even the Toodles, despite all their kindness, fail to convince from a realist perspective: they are too generous, too devoted, too loving, and also too servile toward hierarchy—in short, they resemble many of the workers Dickens describes.[10]

Their goodness serves as a counterbalance to Dombey's ever-present coldness, which stiffens into a kind of comic glaciation.[10] This emotional frigidity, however—unlike that of old Scrooge in A Christmas Carol—does not appear to have any etiological root in childhood: while it is not natural, it nonetheless seems to come to him naturally. It is as though Dombey, enslaved to his temperament and sustained by his pride,[11] ruled over an England in his image—frozen by an almost universal absence of compassion. In this sense, writes Elizabeth Gitter, he becomes “an emblematic figure of a pre-bourgeois order, a synecdoche of the desolate world he inhabits.”[12]

Emergence of new values

[edit]

In this society, money reigns supreme and seems to have given rise to a new system of values, each as negative as the next.[10] Family and human relationships are devalued to the level of mere conveniences: proof of this is Mr. Dombey’s reaction when considering the possible death of his wife—“he would regret it, and he would feel that something would be gone, something that had taken its place among the plates and furniture and all the other worthwhile household possessions, such that losing it could only cause regret.”[13] Similarly, when he hires Polly as a nursemaid, he forbids any emotional bond with the child she is to breastfeed, for, he says, “it is merely a transaction.”[14] To complete the dehumanization, he erases her name and, as was done with slaves, assigns her a surname with no first name, typically reserved for domestic servants.[15]

The secondary characters orbiting around him are also driven by the same selfishness: Major Bagstock, Mrs. Skewton, Mrs. Pipchin, and Mrs. Chick are all motivated by greed, competitiveness, and indifference to the well-being of others. As E. D. H. Johnson writes, the world of “Dombeyism” is nothing more than “a cynical economic system engendering all the vices and cruelties of society.”[16]

As a result, Dombey and Son has been seen as depicting a Mammonist world where wealth corrupts even the most traditionally sacred things, as illustrated in chapters 5, 18, 31, and 57 by scenes taking place in the perpetually darkened grey church, from which emanate only an icy cold, musty dampness, and suffocating dust.[15] In this regard, unlike A Christmas Carol, a socio-economic fantasy, the novel becomes a true study of the urban utilitarianism of the all-powerful business circle, where charity[N 1] is no longer anything but a business like any other—one that must be profitable and, to achieve that, crushes the very people it is supposed to help.[17][N 2]

The stripping of the individual

[edit]Dombey and Son illustrates the process of alienation and reification of the individual, now reduced to a mere commodity.

Alienation and reification

[edit]In the aforementioned article, E. D. H. Johnson points out that “Dickens’s mature novels offer the first example of a reified world, where people have become objects—controlled or manipulated, bought or sold.”[16] Judging by Dombey’s relationship with his first wife, the bargaining that governs the arrangement of his second marriage, and the fragility of friendships that are just as easily formed as broken—between Dombey and Bagstock, Mrs. Chick and Miss Tox, for example—society has become a soulless exchange market where people are juggled like stocks and bonds.[15] In this world, the supreme value is no longer quality but quantity, and individuals are diminished or enhanced as losses or profits. Thus, in chapter 36, it reads: “The next arrival was a bank director reputed to be capable of buying anything—human nature in general—if ever he decided to influence the exchange rates in that direction.”[18]

From pathetic fallacy to synecdoche and reduction

[edit]To make this degradation tangible, Dickens resorts to several devices, the first being what John Ruskin called the pathetic fallacy: thus, the dark “coldness” of the Dombey household, the “gloomy” greyness of the church. Furthermore, the reification of individuals often serves as a means of characterization; people are described, even named, by their attributes—often non-human ones: Dombey’s stiff cravat, his loud pocket watch, his conspicuous gold chain, his creaking leather boots; Carker’s teeth, reminiscent both of a cat and a shark.[2]

Finally, many characters are reduced to a single gesture or some idiosyncrasy that fully sums them up: such is the case with Cousin Feenix and Major Bagstock, both afflicted with verbal diarrhea paired with very specific mannerisms—doublets that characterize them in a formulaic way. They are not alone: whatever the situation, Mr. Toots invariably repeats, “It’s of no consequence,” and Captain Cuttle expresses his feelings through a rigid alternation of putting on and taking off his polished top hat.[15]

An apparent ambiguity

[edit]In Bleak House, he will juxtapose the representatives of two worlds: Sir Leicester Dedlock, the old aristocrat clinging to the ancient order, and Mr. Rouncewell, the powerful and industrious ironmaster of the North. And, overall, he tilts the balance toward what the latter has to offer: enterprise, efficiency, and the call of the future.[19] Moreover, the adjectival expression old-fashioned, which he often uses about Sol Gills and “The Wooden Midshipman” in chapter 4, and later transfers to Little Paul from chapter 16 onward, retains its share of ambiguity,[20] and even, according to Stanley Tick, of “incongruity, even confusion:”[21] from “outdated, obsolete,” it suddenly evokes what Louis Gondebeaud calls “the common fate, mutability, death.”[22] Solomon Gills is not as wise in business as his first name might suggest; he is “behind the times,” incapable of adapting to new economic constraints, forever passive—unlike Walter Gay, whose activity is continually emphasized.[23]

The fortress of old-fashioned values

[edit]Yet, his business is saved from ruin by money—and more specifically, by Dombey’s money—thanks to the miraculous recovery of “old investments,” and equally miraculously, by the return of the lost cargo. He belongs to a past that carries no weight in economic terms but stands against the world like a fortress of the “good old days,” the era favored by early Victorian fiction, and which here provides the key to a happy ending. Its treasures of simplicity and naturalness retain the potential power to one day—perhaps tomorrow—call the prevailing mercantilism to account.

As a result, the guardians of the temple—those entrusted with Christian love, domestic harmony, and innocence of heart—are generously rewarded. As for those who join them, like Mr. Dombey, once their journey of inner initiation reaches its conclusion, they are granted a serene contentment mingled with a resigned nostalgia for missed opportunities.[23]

According to John Butt and Kathleen Tillotson, this is a conclusion all the more effective because it remains “restrained;” initially intended to open outward toward the sea, with waves stretching to the horizon, it ultimately narrows to “the echo of an autumnal beach in the far distance, a grandfather beside a new Little Paul and two Florences.”[24]

Dickens’s attitude toward socio-political issues

[edit]This attitude, consistent with the literary tradition of the Victorian era, has often been criticized. The objections have been summarized by Julian Moynahan, cited by Barbara Weiss, who does not share the novelist’s optimism. Referring to the “back parlor” often mentioned concerning “The Wooden Midshipman,” he writes: “The ‘little society of the back boudoir’ that Dickens promotes as an alternative to the harsh reality of the mid-nineteenth century and its industrial revolution consists of two retired maids, a near-simpleton, a boat pilot so virtuous it's comical, a seller of outdated nautical instruments, and a dull young man named Walter. As for Florence, she is less part of this little group than the object of its adoration.”[25][N 3]

This refuge, however warm it may be, does not appear particularly capable of confronting the future, as John Lucas expresses in these terms: “[Dickens] claims that by making the good people of ‘The Wooden Midshipman’ a sanctuary of old-fashioned values, and by assuming that they will continue to survive and even thrive, albeit in a haphazard way, he is guilty of a true ‘falsification of the evidence.’”[26]

Thus, it would seem that, despite his denunciation of the ills afflicting society, Dickens refused to face reality: his expressed nostalgia for the good old days reflects a constant stance in his work. Present in Dombey and Son, it resurfaces in Bleak House and Great Expectations; Barbara Weiss calls it “the balm of Christian hope.”[26] He believed, wanted to believe, or pretended to believe that only the reaction of well-meaning people could overcome the upheavals affecting his country and, with it, the whole of Europe—that “the values of the heart” would suffice to defeat the mechanical harshness at work in society.[27]

His attitude toward money is clearer, though not without ambiguity: at the beginning of the novel, he satirizes what he calls “mercenary values,” and while he condemns materialism, he also attributes to money a redemptive power. The ending presents a purified version of it, since with Walter, business becomes more humane, and the former mercantilism appears sanitized by kindness and even charity.[27] Thus, bankruptcy, according to Barbara Weiss, “functions as a kind of redemptive suffering from which the mercantile hero is morally reborn.”[26]

All in all, Dickens seems to reconcile capitalism and Christian values by making them compatible. This is why the ending appears both exemplary of the sentimental vein and aligned with the principles favored by his social class—the warmth of the home with Solomon Cuttle, the respect for hierarchy with the Toodles. Except for Susan Nipper, whose tongue is as sharp as her eyes are black, all the servants remain submissive and respectful toward their masters. It is only in the kitchen and the attic that they gently allow themselves to express what they think; moreover, their individualism is often hindered by domestic rivalries that mirror those of the powerful who employ them—the basement mimicking the upper floors. Finally, the ultimate gathering of all the “good” characters around the bottle of old Madeira symbolizes the triumph of goodwill, a conclusion that may be implausible but was the “obligatory ending in the first half of the nineteenth century.”[28]

On September 27, 1869, nine months before his death, Dickens delivered a speech in Birmingham before the Birmingham and Midland Institute:

My confidence in the rulers is, on the whole, infinitesimal; my confidence in the People, the governed, is, on the whole, unlimited.[29]

This remains, in essence, the core philosophy emerging from Dickens's overall vision of the society of his time, as portrayed in Dombey and Son.[28]

The vision of femininity

[edit]Dickens was not a feminist and never conceived of his novels, and particularly Dombey and Son, as a conscious demonstration of any doctrine regarding the condition of women. However, the novel contains a powerful vision of femininity, one of its major themes, which permeates the story and provides it with its most dynamic and poetic impulses.[30]

Blood and money

[edit]Mr. Dombey is very wealthy, but he did not build his fortune himself, as he inherited it from his grandfather and then from his father, whose name he venerates, having inherited it as his own. This is constantly reiterated by Major Bagstock, the master flatterer, who refers to it as the "great name."[31] There is a certain irony in this from Dickens, as Dombey is anything but a "great name." His surname is rather plebeian and phonetically very close to "donkey," meaning "ass," which immediately makes him somewhat ridiculous.[30] Nothing is said about his ancestors, but their name suggests that they were upwardly mobile bourgeois, not connected to the aristocracy. Mr. Dombey is fully aware of this flaw and, to compensate for this innate inferiority, he leads a grand lifestyle and composes a mask of icy dignity, hoping it aligns with the ways of the caste from which he is excluded. During the nineteenth century, the nobility and the bourgeoisie remained antagonistic classes, with the former considering itself the hereditary elite, imbued with chivalric spirit and bound by a code of honor, while the latter concerned itself with labor and profitability.[30]

In Dombey and Son, aristocracy is represented by Mrs. Skewton, her daughter Edith, and their cousin Feenix, who are symbolic of a decadent and ruined caste. The first turns out to be a mercenary mother, whose sole concern is to live off the beauty and aristocratic connections of her daughter. Dickens has taken care to give her the physical traits of the job: decrepit, ruined by idleness, wearing the mask—yet with what luxurious preparation!—of elegance, with a facade of behavior layered over a black hypocrisy that is both calculating and flowery. In this respect, she resembles "Good Mrs. Brown," though one could say she mimics her a few districts away: Good Mrs. Brown is a cantankerous vagrant who sold her daughter Alice Marwood to Mr. Carker, fully aware of the terrible fate that awaited her—prostitution and delinquency; but Mrs. Skewton is preparing to do the same by bargaining the venal value of her child down to the penny, planning to throw her into the arms of Dombey.[30] Françoise Basch notes that Mrs. Skewton is a fierce caricature of a match-making mother, with a greed that mirrors that of Good Mrs. Brown, though hers is manifested in a more sordid way: two unworthy mothers positioned at the two extremes of the social ladder.[32]

For while Dombey does not belong to the aristocracy, he possesses wealth, which explains why this marriage is universally considered a "transaction," or even a "bargain:" Edith sells her "blood," as Major Bagstock aptly puts it, having worked as a broker, and her undeniable beauty in exchange for the fortune of a man willing to marry her with no dowry other than her natural assets, which, in Victorian England, remains improper. Françoise Basch writes that "the role of mothers as intermediaries in these transactions is decisive."[32] Both spouses are fully aware of the commercial aspect of their union, which Dickens intends from the outset to fail due to a flaw in its nature.[30] However, this practice was not uncommon at the time, though it remained a target of literary satire, which, by denouncing accepted abuses, sought to instill more morality into human relationships.[33]

Mr. Dombey represents the upper-middle class; he is also a merchant from the City, a symbol of triumphant British capitalism. However, Dickens sought to impose a sense of decadence on the character: instead of simply taking pride in his success, the powerful businessman aspires to aristocratic elegance, showing that he has lost the energetic spirit that once fueled the pioneers. Dombey takes pleasure in contemplating his grandeur, which he obsessively seeks to pass on to a son. Thus, he has delegated his authority to James Carker, who ruins him, and does almost nothing himself; furthermore, the business "Dombey and Son" is already outdated, "old-fashioned," just like the presumptive heir, Little Paul.[33]

The thematic analogy between the sea and femininity

[edit]-

Mansion House, in the City of London.

-

Crampton locomotive, built from 1846.

-

The Cosmos, author unknown, Paris 1888; colorization: Hugo Heikenwaelder, 1998.

Nevertheless, Mr. Dombey remains a powerful man, head of a maritime transport business headquartered in the mercantile heart of London, the nerve center of English capitalism. He owns agencies and outposts scattered across the oceans in "an empire on which the sun never sets."[34] This connects him to Major Bagstock, a former officer of the colonial troops: Dombey knows what he owes to the army, and Bagstock to the success of the merchants; it is to Barbados that Walter is sent, and at the major's in London remains a relic, the "native," which suggests that Dombey's fortune long depended on the slave trade,[35] recently abolished on January 1, 1838.[36] Certainly, Dombey's rigid dignity contrasts with the coarse vulgarity of the major, but there is a real solidarity between them, as they embody a vision of the Empire that is already outdated.[37] Thus, Dombey is professionally linked to the sea, but he does not understand it, exploiting it without seeing it as anything other than a vast nothingness and an insurance payout when it steals one of his ships, without a tear shed for the lost crew; he has appropriated the sea with his money, but he does not possess it, just as his money cannot bring back his son or buy his wife's love.[37] His sympathy lies rather with the railway, a destructive embodiment of the new industrial efficiency, which mutilates neighborhoods, has killed Carker, and relentlessly reminds him, during trips to Leamington Spa, of the death of his heir, marked at every length of the track. There are two forces at play here, one feminine, the other masculine, symbolically at war with each other.[37][38]

Yet, the infinite sea, the origin of all beginnings and all ends,[39] represents Nature and the Cosmos, whose language remains inaccessible to those confined by the narrow alleys of society. Life is a river that flows into its waters,[40] and only the prematurely sensitive child knows how to harmonize with it and discern what is being said beyond the waves; with him, a few candid and open hearts—Captain Cuttle, "the dry man," Solomon Gills, "the man with gills," Walter Gay, whose name evokes "the happy ploughman" or "the harmonious blacksmith"—escape its perils.

The thematic analogy between the sea and femininity sheds light on one of the novel's most crucial aspects, the relationship between men and women and, more specifically, between masculine authority and feminine submission. Dickens endowed Mr. Dombey with boundless pride, making him both a tyrant and a victim. For while he reigns as master of his household, he knows nothing of the world of love, particularly that offered by the women of his home—his wife and his daughter. Moreover, while he mentions his father and grandfather on several occasions, he never once mentions his mother. Driven by the system to perpetuate his name with the arrival of a male heir, the inferior status he grants to women becomes an evident truth to him: transmitting life to a daughter is sacred, but transmitting it to a son is far more so. In this sense, the novel presents a fatal conflict between nature and society: since society prioritizes males, the female aspect of nature is morally annihilated; Mr. Dombey, by blindly following the prescribed path, is immediately condemned.[41]

Indeed, in Dombey and Son, women do not only represent motherhood, but outside of this essential attribute, Dombey cuts himself off from everything else. After the death of his first wife, a tragedy for Florence, a culpable lack of will for Mrs. Chick, a disturbing circumstance for Dombey, a sacrifice for the reader, and a loss, fortunately repaired by the birth of a male baby, for society, a nurse becomes indispensable to provide the missing breast to this blessed offspring. It is Miss Tox who finds the nurse, not without ulterior motives, as she aspires to become the second Mrs. Dombey, though her feelings are sincere, which the recipient is completely incapable of discerning, being focused only on the love he receives and his projection into the little heir. In the same way, he remains blind to the unwavering devotion of his daughter toward him and indifferent to the tireless efforts she makes to comfort him after the death of Little Paul.[41] In contrast, the wet nurse, Polly Toodle, compared to an apple or an apple tree, symbolizes fertility; she has many children whom she cherishes equally, even The Grinder, though corrupted by Mr. Dombey's mercenary generosity.[42] Only her poverty forces her to leave them to care for Little Paul, so that she finds herself parasitized by her new master, who drains her milk while denying her the right to love the child whom this bounty nourishes. The transgression of the imposed order, when she goes to see her children with Little Paul, Florence, and Susan Nipper, will lead to her dismissal, which seals the fate of the young boy: deprived of this nourishing milk and love, he will wither away in Brighton at Mr. Blimber's school and die there.[42]

This death represents the punishment that immanent justice inflicts upon Dombey, a victim of the isolation caused by his social prejudices, his contempt for women—his wife, his daughter, the nurse of his child. Unlike his little boy, who knew of her kindness and delighted in her mysteries, he remained blind to the fertility of nature symbolized by the fluidity of the ocean and feminine love,[39] this love, as John O. Jordan writes, which connects, like the waves of the sea, the past to the present and the present to the future;[43] now a victim of his alienation, he will endure the rebellion of his second wife and the flight of his loving daughter, tormenting experiences similar to those which, Dickens writes, "shake the waves," a reminder of the smallness of human beings in the face of the metaphysical power that generates birth and death, speaking the mysterious language that small minds and nurturers like the milk of femininity do not understand.[42]

The literary status of women

[edit]In Dombey and Son, certainly an artistic work and not a treatise, Dickens sought to express his views on the condition of women and assert his opinion in a way that could be understood. In this respect, this novel is one of the most explicit he ever wrote.[44]

The character of Florence Dombey was created by Dickens to serve as a demonstration:[45] The contrast is profound between this child, overflowing with love, angelic goodness, and fervent self-forgetfulness, a precursor to the qualities of other heroines like Esther Summerson or even Biddy, and the systematic rejection made by her father, who thus affirms his conviction in the being of masculinity and the non-being of femininity. In truth, this antagonism, all the more painful because it is one-sided, and which the reader cannot contemplate without suffering, becomes emblematic of a general situation;[44] thus, Dombey’s sister, a foolish woman but sharing her brother's narrow pride, is treated by him, without always realizing it, with the same contempt, which she accepts not out of affection or generosity, nor even resignation, but because she finds herself unknowingly subjected to the system he has established and to which she adheres, even sacrificing her friend Lucretia Tox.[42]

Alice Marwood and Edith Granger participate in the same demonstration.[42] Alice represents a type of woman often exploited in 19th-century English fiction, especially in its second half: the young girl seduced, corrupted, and then abandoned by a wealthy man, condemned to fall into delinquency and prostitution. Edith, conceived in parallel with Alice, implies that her marriage to Dombey is also a form of prostitution.[N 4] Alice Brown becomes Alice Marwood, with mar suggesting waste, damage, and the corruption of integrity. As for Edith, it is the course of life that transforms her from Skewton to Granger and then to Dombey. Likewise, when Polly Toodle becomes Mrs. Richards, it also participates in the symbolism suggesting that, by losing their name, women relinquish their identity.[42]

Other women are presented as victims in the novel. Mrs. Wickam, whose servile condition makes her doubly unhappy, is both a servant and married to a valet who has made her his domestic servant. One of the most pathetic characters is Berry, also known as Berinthia, the niece and slave of Mrs. Pipichin in Brighton, to the extent that when an honest grocer asks for her hand, he is rejected with contempt (Dickens redundantly writes "contumely and scorn") by the mistress of the house. Orphaned and deprived of any means, physically and socially sequestrated, Berry can only accept what this aunt decides for her, and she does so with the gratitude of a heart conditioned to see her as her benefactor.[46]

The flirtation between Mrs. Skewton and Major Bagstock proves to be merely diplomatic maneuvering, for beneath the pleasant surface lies mutual mistrust and the harshness of business. In this war between the sexes, women sometimes gain the upper hand, with the most amusing example being Mrs. MacStinger, the owner of Captain Scuttle, who keeps everyone in line like a confirmed shrew ("sting"): with this tender-hearted sailor, her method never changes—it is one of terrorism that reduces him to obedience and silence, and her marriage to Captain Bunsby, whose name means "bun," destined to be quickly devoured by the acrid woman, resembles a true kidnapping. However, the grotesque farce of these situations cannot disguise the mass of pain Dickens exposes: it is fear and humiliation that govern relations between the sexes.[46]

Nevertheless, a woman must inevitably marry, with spinsters and widows condemned to precariousness: thus, the race for a husband becomes a constant preoccupation, even when, like Mrs. MacStinger, the huntress who despises the opposite sex, which allows Dickens to depict scenes of farcical comedy that, through repetition, end up revealing a real suffering beneath the burlesque surface.[46] In any case, as often in his works, the majority of couples either tear each other apart or remain silent about their unhappiness in frustrating resignation. In Dombey and Son, only the Toodles, and later Walter and Florence, experience happiness, but these are exceptional couples, idealized to the extreme, benefiting forever from the incorruptible innocence of their youthful years. In contrast, Mr. and Mrs. Chick engage in a permanent struggle, not to mention the opposition between Mr. Dombey and Edith, all conflicts generated by the flawed Victorian marriage system.[47]

The daily life of women

[edit]Often large families

[edit]Almost always, families are large, as confirmed by demographic data provided by historians.[48] Thus, Mrs. Perch, the messenger's wife, frequently becomes pregnant. In this, she is no different from Dickens' wife. Some critics have suggested that Dickens wanted to highlight the fertility of the lower classes, in contrast to those who held the fate of the country, as he will emphasize when describing the decrepit sterility of the Dedlocks, which is countered in Bleak House by the healthy and joyful fertility of the Bagnets.[49] Even though Dickens uses his benevolent humor to portray these large families, the modern reader cannot remain indifferent to the harshness of the repeated pregnancies, difficult births, miscarriages, and even maternal deaths, as with the first Mrs. Dombey. Moreover, Dickens tirelessly denounced the deplorable hygiene, often caused by an incongruous tradition of modesty during childbirth, where the parturient, out of false decency, remains half-standing on a sort of stool while the baby is extracted from numerous protective petticoats.[47]

The fate of unmarried sisters

[edit]

Another set of episodes provides the modern reader with insight into the life of a particular category of women—unmarried sisters, such as Polly Toodle’s sister, poetically named Jemima ([dʒe'maimə]), who lives with the couple and whose task is to look after the well-being and education of her nephews and nieces while Polly works as a nurse for Dombey. Jemima is an integral part of the family, but, in compensation, she takes on the duties of a servant without any remuneration. Once again, a comparison is warranted with Dickens' situation, as his sister-in-law Georgina Hogarth spent her entire adolescent and adult life serving her illustrious brother-in-law, whom she chose to follow after her separation from her sister, Dickens' wife.[50] Harriet Carker also seems to have sacrificed herself for her brother, John Carker the Elder: after he committed a theft in his youth, he was not only denied any hope of promotion but condemned to a life of poverty, penitence, and mortification. For Harriet, whom Sylvère Monod describes as having "as much animation and spontaneity as an ironing board," it seemed entirely natural to dedicate her life to serving him as a governess, even after she eventually married Mr. Morfin, "another saint."[51] Her two brothers hold her in particularly high regard,[N 5] but her life is still destined for self-sacrifice, the vicarious atonement for her brother’s "crime," celibacy, and the denial of motherhood. This particular case illustrates the fate of many women who erase their personal lives to dedicate themselves to their parents, siblings, or even an aunt or uncle, which sharply contrasts with the status of boys who, upon reaching adulthood, gain independence and freedom.[52]

Marriages, mostly of convenience

[edit]Some minor female characters marry during the novel. This is the case with Cornelia Blimber, who marries Mr. Feeder seemingly for professional reasons. A more cheerful union is that of Susan Nipper and Mr. Toots, although there remain questions about the sincerity of their commitment. Susan is lively, intelligent, and quick-witted, yet remains uneducated; Toots, on the other hand, is foolish but rich, and he has essentially settled for the maid after having coveted Florence, his mistress, who would never have had him. Consequently, Toots constantly justifies his choice, exaggerating the significance of his wife's judgments: he, a good man, married a servant, and this, in a way, requires an excessive apology.[53] And why does Edith Granger, presented as a woman of character, intelligent and even rebellious, fully aware, as a woman of thirty, of the moral implications of her conduct, not revolt against her odious mother, to whom she can, after all, speak her mind? Why does she not refuse the role to which, against her will, she is forced? The question itself implies its answer: such alienation highlights the weight of social and moral conventions which, with rare exceptions, crush the feminine spirit with prohibitions, taboos, and induced inhibitions, denying women their freedom of identity.[52]

A true feminine freemasonry

[edit]A real solidarity between women runs throughout the novel:[54] these suffering girls and women understand each other and help each other because they, unlike many of the men around them, know what love, affection, empathy, and comfort truly mean. This has led some to speak of a kind of "feminine freemasonry" in Dombey and Son, which often transcends social divides and even bypasses hierarchical structures. What is portrayed here is more than mere complicity or emotional support: the immense capacity for love demonstrated by most of the women in the novel turns out to be a redemptive force, clearly illustrated by the conclusion. The pride of the proud and unyielding Mr. Dombey eventually yields to the humblest of kindnesses. This miracle, which in other contexts might seem utopian, here takes on a semblance of normality, so unrelenting, indomitable, and convincing is the affectionate power of the women in his final circle, chiefly his daughter Florence, accompanied by Susan Nipper, the new Mrs. Toots.[55]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Charity is mocked through the portrayal of fanatical philanthropists, such as Mrs. Jellyby and Mrs. Pardiggle, in Bleak House.

- ^ The term grinders, which includes grind ("to crush, grind"), refers to the charitable residents of hospices so poorly fed that they are reduced to grinding bones for sustenance.

- ^ The characters named here are Mrs. Toots, Susan Nipper, Polly Toodle, Mr. Toots, Captain Cuttle, Solomon Gills, and Walter Gay.

- ^ The mercantile marriage is referred to as "legal prostitution" by authors as diverse as Mary Wollstonecraft in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) and Stendhal in On Love (1832).

- ^ The 19th century was a highly emotional period; there was much weeping and open display of feelings, especially between siblings. The strong attachments between William and Fanny Price in Jane Austen's Mansfield Park, as well as those of Wordsworth and Dorothy, Chateaubriand and Lucile, or Felix Mendelssohn and Fanny, are examples of this.

References

[edit]- ^ Cockshut 2003, p. 97

- ^ a b Gilmour, Michael J. "Animal Imagery in Charles Dickens' Dombey and Son". Archived from the original on April 1, 2015.

- ^ a b Ferrieux 1991, p. 72

- ^ a b Dickens 1995, p. 60

- ^ Judge, Roy (1991). May Day and Merrie England. pp. 131–134.

- ^ a b Dickens 1995, p. 413

- ^ a b c d Ferrieux 1991, p. 73

- ^ Dickens 1995, pp. 78–79

- ^ Dickens 1995, p. 390

- ^ a b c d e Ferrieux 1991, p. 74

- ^ Paroissien 2011, pp. 358–359

- ^ Gitter, Elizabeth (2004). "Dickens's Dombey and Son and the Anatomy of Coldness". Essays on Victorian Fiction, Dickens Studies Annual. 34.

- ^ Dickens 1995, p. 9

- ^ Dickens 1995, p. 19

- ^ a b c d Ferrieux 1991, p. 75

- ^ a b Johnson 1985, p. 74

- ^ Palmberg, Elizabeth (2004). "Clockwork and Grinding in Master Humphrey's Clock and Dombey and Son". Essays on Victorian Fiction, Dickens Studies Annual. 34. Santa Cruz: University of California.

- ^ Dickens 1995, p. 449

- ^ Ferrieux, Robert (1993). Bleak House. Perpignan: Université de Perpignan Via Domitia. p. 50.

- ^ Ferrieux 1991, p. 76

- ^ Tick 1975, p. 396

- ^ Gondebeaud 1991, p. 11

- ^ a b Ferrieux 1991, p. 77

- ^ Butt & Tillotson 1957, p. 113

- ^ Weiss 1986, p. 123

- ^ a b c Weiss 1986, p. 124

- ^ a b Ferrieux 1991, p. 78

- ^ a b Ferrieux 1991, p. 79

- ^ Dickens, Charles. "Speeches: Literary and Social". Archived from the original on September 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Ferrieux 1991, p. 81

- ^ Dickens 1995, p. 115

- ^ a b Basch 1976, p. 203

- ^ a b Ferrieux 1991, p. 82

- ^ Wilson, John (1829). "Noctes Ambrosianae". Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. XXV (42): 527.

- ^ Jordan 2001, p. 41

- ^ Pétré-Grenouilleau, Olivier (2004). Les traites négrières, essai d'histoire globale [The slave trade, an attempt at global history] (in French). Paris: Gallimard. p. 267. ISBN 2-07-073499-4.

- ^ a b c Ferrieux 1991, p. 83

- ^ Aisenberg, Nadya. The Progress of Dombey: or All's Well That Ends Well.

- ^ a b Hillis-Miller 1958, p. 179

- ^ Dickens 1995, p. 1 (Introduction)

- ^ a b Ferrieux 1991, p. 84

- ^ a b c d e f Ferrieux 1991, p. 85

- ^ Jordan 2001, p. 42

- ^ a b Ferrieux 1991, p. 86

- ^ Jordan 2001, p. 40

- ^ a b c Ferrieux 1991, p. 87

- ^ a b Ferrieux 1991, p. 88

- ^ "L'Angleterre victorienne : paradigme mondial urbain" [Victorian England: the urban world paradigm] (in French).

- ^ Gondebeaud 1991, p. 8

- ^ Schlicke 2000, p. 277

- ^ Monod 1953, p. 228

- ^ a b Ferrieux 1991, p. 89

- ^ Ferrieux 1991, p. 90

- ^ Gondebeaud 1991, p. 10

- ^ Ferrieux 1991, p. 91

Bibliography

[edit]- Dickens, Charles (1995). Dombey and Son. Ware: Wordsworth Editions Limited. ISBN 1-85326-257-9.

Life and work of Charles Dickens

[edit]- Forster, John (1874). The Life of Charles Dickens. London: J. M. Dent & Sons.

- House, Humphry (1941). The Dickens World. London: Oxford University Press.

- Johnson, Edgar (1952). Charles Dickens : His Tragedy and Triumph. 2 vols. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Monod, Sylvère (1953). Dickens romancier [Dickens novelist] (in French). Paris: Hachette.

- Butt, John; Tillotson, Kathleen (1957). Dickens at Work. London: Methuen.

- Hillis-Miller, John (1958). Charles Dickens, The World of His Novels. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Cockshut, A. O. J (2003) [1962]. The Imagination of Charles Dickens. New York: Textbook Publishers [New York University Press]. ISBN 9780758177353.

- Marcus, Steven (1965). Dickens : From Pickwick to Dombey. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Leavis, F. R; Leavis, Q. D (1970). Dickens the Novelist. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-1644-7.

- Basch, Françoise (1976). Romantisme [Romanticism]. Mythes de la femme dans le roman victorien (in French). Persée.

- Slater, Michael (1983). Dickens and Women. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. ISBN 0-460-04248-3.

- Ackroyd, Peter (1993). Charles Dickens. London: Stock. ISBN 978-0-09-943709-3.

- Schlicke, Paul (2000). Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866253-X.

- Davis, Paul (1999). Charles Dickens A to Z : the essential reference to his life and work. New York: Facts on file. ISBN 0-8160-2905-9.

- Jordan, John O (2001). The Cambridge companion to Charles Dickens. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66964-2.

- Paroissien, David (2011). A Companion to Charles Dickens. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-65794-2.

- Page, Norman (1984). A Dickens Companion. New York: Schocken Books.

Dombey and Son

[edit]- Moynahan, Julian (1962). Dickens and the Twentieth Century : Dealings with the Firm of Dombey and Son: Firmness versus Wetness. Toronto: John Gross and Gabriel Pearson, University of Toronto Press.

- Axter, W (1963). "78. Tonal Unity in Dombey and Son". PMLA. pp. 341–348.

- Johnson, Edgar (1985). "The World of Dombey and Son". Dickens. Casebook Series. London: MacMillan. pp. 69–81.

- Andrews, Malcolm (1994). "Dombey & Son: the New Fashioned Man and the Old-Fashioned Child". Dickens and the Grown-Up Child. London: MacMillan.

- Arac, Jonathan (1978). "The House and the Railroad: Dombey & Son and The House of the Seven Gables". New England Quarterly. 51. pp. 3–22.

- Auerbach, Nina (1975). "Dickens and Dombey: A Daughter after All". Dickens Studies Annual 5. pp. 49–67.

- Baumgarten, Murray (1990). "Railway/Reading/Time: Dombey & Son and the Industrial World". Dickens Studies Annual 19. pp. 65–89.

- Berry, Laura C (1996). "In the Bosom of the Family: The Wet Nurse, The Railroad, and Dombey & Son". Dickens Studies Annual 25.

- Clark, Robert (1984). "Riddling the Family Firm: The Sexual Economy in Dombey & Son". ELH. 51.

- Collins, Robert (1967). "Dombey & Son-Then and Now". Dickensian. 63.

- Donoghue, Denis (1971). "The English Dickens and Dombey & Son". Dickens Centennial Essays. Berkeley: University od California Press. pp. 1–21.

- Flint, Kate (2001). "The Middle Novels: Chuzzlewit, Dombey, and Copperfield". The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens, ed. John O. Jordan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tick, Stanley (1975). "The Unfinished Business of Dombey and Son". Modern Language Quarterly. Washington: Duke University Press. pp. 90–402.

- Green, Michael. "Notes on Fathers and Sons from Dombey & Son in 1848". The Sociology of Literature. Colchester, University of Essex, 1978.

- Tillotson, Kathleen (1954). Dombey & Son in Novels of the Eighteen-Forties. Clarendon Press.

- Tillotson, Kathleen (1968). "New Readings in Dombey & Son". Imagined Worlds : Essays on Some English Novels and Novelists in Honour of John Butt, ed. Maynard Mack et al. Methuen.

- Weiss, Barbara (1986). The Hell of the English : Bankruptcy and the Victorian Novel. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press. ISBN 0-8387-5099-0.

- Wiley, Margaret (1996). "Mother's Milk and Dombey's Son". Dickens Quarterly 13. pp. 217–228.

- Zwinger, Lynda (1985). "The Fear of the Father: Dombey & Daughter". Nineteenth-Century Fiction. 39. pp. 420–440.

- Ferrieux, Robert (1991). Dombey and Son. Université de Perpignan Via Domitia.

- Gondebeaud, Louis (1991). Dombey and Son (in English and French). Pau: University of Pau and the Pays de l'Adour.

External links

[edit]- "Dombey and Son". gutenberg.org. Archived from the original on January 18, 2019.