User:UndercoverClassicist/Theodore Leslie Shear

Theodore Leslie Shear | |

|---|---|

Photographed in 1936 with a statue of the Apollo Lykeios type | |

| Born | August 11, 1880 New London, New Hampshire |

| Died | July 3, 1945 (aged 64) |

| Resting place | Princeton, New Jersey |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 2 |

| Academic background | |

| Education | |

| Thesis | The Influence of Plato on Saint Basil (1904) |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| Institutions | |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | US Army Air Service |

| Rank | 1st Lieutenant |

| Wars | First World War |

Theodore Leslie Shear (August 11, 1880 – July 3, 1945) was an American classical archaeologist.

Early life and career

[edit]Theodore Leslie Shear was born in New London, New Hampshire, on August 11, 1880.[1] He was educated at Halsey Collegiate School,[2] a preparatory school for boys in New York,[3] before obtaining a bachelor's and a master's degree from New York University,[4] where he studied under Ernest Gottlieb Sihler.[2] He took his doctorate in 1904 from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.[4] His doctoral thesis, which he published in 1906, was titled The Influence of Plato on Saint Basil; in it, he thanked his teachers, including the philologists Basil L. Gildersleeve and Maurice Bloomfield, and credited Gildersleeve with particular influence upon his work.[2]

At the age of twenty-four, Shear became the University Fellow of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), an archaeological research institute and one of Greece's foreign schools of archaeology.[4] He spent the 1904–1905 academic year in postdoctoral study at the University of Bonn,[1] under Georg Loeschcke.[5] He took a post teaching Greek and Latin at Barnard College, a private women's college in New York, in 1906.[6] In 1910, he moved to Columbia University, where he taught Greek as an associate professor until 1923.[1] Over the course of his career, he took an increasing interest in classical archaeology, rather than the literary studies with which he had begun.[6] In 1911, he took part in trial excavations at Knidos in Asia Minor;[7] he also participated in the excavations of Sardis under Howard Crosby Butler, which took place between 1911 and 1914.[8]

Shear married Nora Jenkins, an artist and archaeologist educated at the École du Louvre in Paris, in 1907:[9] they had a daughter, Chloe Louise Smith.[10] The couple sailed around the eastern Mediterranean on a small yacht; they were on Rhodes in May 1912, when the Ottoman garrison surrendered the island to invading Italian forces.[11]

During the First World War, which the United States entered in 1917, Shear was an officer in the United States Army Air Service, reaching the rank of first lieutenant.[9] He was consulted on strategic matters concerning the Mediterranean, on the basis of his knowledge of the area.[5] In 1921, he became a lecturer in classics at Princeton University in New Jersey.[12] A small geometric and classical site was discovered in the same year on Mount Hymettus near Athens by J. M. Prindle of Harvard University;[13] Carl Blegen, then assistant director of the ASCSA,[14] made an exploratory excavation there in 1923.[15] Shear excavated the site in 1924, meeting the project's expenses from his own money.[9]

Excavations of Corinth

[edit]

In 1924, Shear negotiated the resumption of the ASCSA's excavations at Corinth, an ancient city on the isthmus between the Peloponnese and central Greece,[9] which had been halted since 1915.[a] Shear offered to pay a total of $10,000 (equivalent to $183,000 in 2024) over two years, on the condition that the ASCSA would allocate to the project a donation of the same size that had previously been given by the banker J. P. Morgan Jr. for excavations, "preferably at Corinth", and a donation of $1,000 (equivalent to $18,000 in 2024) from Morgan's wife, Jane Norton Grew.[17] He donated $6000 (equivalent to $107,000 in 2024) in the year 1925–1926 towards the project, of which $5000 (equivalent to $89,000 in 2024) was to be used to build the a house named after him.[18]

The original plan for the Corinth excavation was for Shear to excavate in the area of the theater, while Bert Hodge Hill, the ASCSA's director, would excavate the city's agora.[b] However, a shortage of workers meant that the two excavations had to follow each other, with Shear's commencing first. He began excavating on March 9, 1925, with the assistance of Nora Shear, Oscar Broneer, Charles Alexander Robinson Jr. and Richard Stillwell, who made drawings of the finds.[20] In April of the same year, he began excavating the site of a large dwelling, known as the "Roman villa", to the north of the Acrocorinth,[21][c] while his 1925 season also included the excavation of the site's North Cemetery.[23]

During the 1926 season, Shear excavated at Corinth from March until July, with Nora Shear, Broneer, Stillwell (now employed as the excavation's architect), Edward Capps Jr., and John Day, a fellow of the ASCSA. Shear established the location of the Sanctuary of Athena Chalinitis, a major objective of the Corinth project, which was known from the travelogues of the second-century CE Greek writer Pausanias.[24] He also cleared the orchestra and skene of the theatre.[25] Shear was accompanied on the initial seasons by Nora, who with him reorganized the site's museum;[d][28] there was no excavation in that year.[29] She died later in 1927 of pneumonia;[9] Shear dedicated his publication of the "Roman villa", to which she had contributed watercolour reproductions of the site's mosaics, to her memory.[30]

In 1928, Shear was promoted to become professor of classical archaeology at Princeton.[6] The year, the new director of the ASCSA, Rhys Carpenter, took over overall direction of the Corinth excavations. Shear's season ran from February 22 to June 6, he excavated the east parodos of the theater, as well as a paved road to its east, and made small-scale excavations at the Sanctuary of Athena Chalinitis. He also excavated thirty-three graves in a cemetery north-west of the theatre, which had previously been discovered by Hill and William Bell Dinsmoor in 1915.[31] Between February 20 and July 15, 1929, he excavated with Stillwell and Ferdinand Joseph Maria de Waele, a Belgian-born archaeologist who had been given a part-time position as "Special Assistant in Archaeology" at the ASCSA, clearing the central area of the theater's cavea and the west parodos and discovering a road running along the building's western side. At the north-eastern edge of the theater, Shear discovered an inscription crediting one Erastus for laying the paving, and suggested that this may have been the Erastus of Corinth named by Paul the Apostle in his Epistle to the Romans.[32] He also excavated an intramural cemetery dating to the fourth and third centuries BCE in the eastern part of the city, and further graves in the North Cemetery; his work here established that it had been used as a burial ground since the Middle Helladic (that is, since at least c. 1550 BCE).[33]

In the campaign of 1930, which ran from January 27 to May 10, Shear excavated a further 235 graves in the North Cemetery and 113 at another nearby site, known as Cheliotomylos. In the process, he confirmed the suggestion made earlier by Blegen that Corinth had been inhabited on a large scale during the Neolithic period.[34]

Athens and later life

[edit]

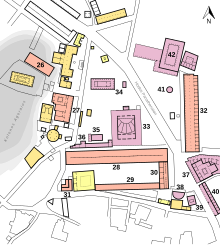

At the end of May 1930, Shear left Corinth for the Athenian Agora, where he had been appointed to lead the ASCSA's excavations.[23] Although the initial plan was for Shear to serve as the project's field director, under Rhys Carpenter as general director, Carpenter was never appointed, and Shear had total control over the excavations.[35] These began in 1931,[9] largely funded by John D. Rockefeller Jr.,[36] though the first season consisted only of minor exploratory work.[37] That year, Shear returned to Corinth to make further excavations of tombs in Cheliotomylos.[38]

The 1932 season was more substantial; excavation was conducted for a period of six months. The work uncovered the Stoa Basileios, the Agora's Great Drain, and the Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios, as well as a statue of the Roman emperor Hadrian believed to be that described by Pausanias as standing in front of the latter building.[39] During the 1933 season, which ran from February to July, parts of the Bouleuterion were uncovered, as well as inscriptions placing the Metroon in the area south and east of the Stoa Basileios, and parts of the late Roman Valerian Wall.[40] In the excavation season between January 22 and May 12, 1934, he uncovered the Tholos, secured the location of the Bouleuterion and the Metroon, and discovered the Temple of Apollo Patroos and the Altar of the Twelve Gods.[41]

The Agora excavations continued until the end of the 1940 season, when the Second World War forced their postponement.[42]

Shear died on July 3, 1945,[1] of a stroke suffered while on holiday at Lake Sunapee in New Hampshire.[6] He was buried in the old cemetery at Princeton.[43]

Assessment, legacy, and personal life

[edit]

In a 1998 biography, Rachel Hood credited Shear with training "a generation of young scholars" through the Corinth excavations, and with recording the finds from the Agora in "hitherto unsurpassed detail".[9] In a review of Shear's Festschrift, published by the ASCSA in 1949, the British classicist John Manuel Cook called him one of the "great men" of the school.[44] The archaeologist Louis E. Lord praised the care with which Shear excavated in the Agora, pointing to his collection and cataloguing of over a thousand stamped amphora handles from the Mycenaean period.[45]

Shear remarried in 1931, to Josephine Platner, also an archaeologist.[9] She excavated with him at Corinth, supervising in 1931 the excavation of a second-century CE Roman tomb known as the "Shear Painted Tomb".[23] Their son, Theodore Leslie Shear Jr., was born in 1938,[9] and also became an archaeologist.[10] The younger Shear followed his father as director of the Agora excavations,[9] leading them between 1968 and 1993.[5]

Shear's son recalled that he affected a formal, reserved demeanour: he tended to excavate in a suit and tie. In his private life, he enjoyed drinking cocktails and had interests in stamp collecting and American football – he supported the Princeton Tigers and attended their games whenever he could. He had two Samoyed dogs, and kept a photograph of them on his desk.[46]

Published works

[edit]- Shear, T. Leslie (1904). The Influence of Plato on Saint Basil (PhD thesis). Johns Hopkins University.

- — (1913). "Inscriptions from Loryma and Vicinity". American Journal of Archaeology. 34 (4): 451–460. JSTOR 289383.

- — (1914). "A Sculptured Basis from Loryma". American Journal of Archaeology. 18 (3): 285–296. JSTOR 497222.

- — (1922). "Sixth Preliminary Report on the American Excavations at Sardes in Asia Minor". American Journal of Archaeology. 26 (4): 389–409. JSTOR 497951.

- — (1924). "A Marble Copy of Athena Parthenon is Princeton". American Journal of Archaeology. 28 (2): 117–119. JSTOR 497731.

- — (1926). Terra-cottas: Part I: Architectural Terra-cottas. Sardis. Vol. 10. Cambridge University Press. OCLC 1000688644.

- — (1933). "Review: Iconographie de l'Iphigénie en Tauride d'Euripide, H. Phillippart". American Journal of Archaeology. 31 (4): 527–528. JSTOR 497882.

- — (1930). The Roman Villa. Corinth. Vol. 5. London, Oxford and Leipzig: American School of Classical Studies at Athens. JSTOR i403360.

- — (1933). "The Progress of the First Campaign of Excavation in 1931". Hesperia. 2 (2): 96–109. JSTOR 146504.

- — (1933). "The Campaign of 1932". Hesperia. 2 (4): 451–474. JSTOR 146653.

- — (December 1, 1933). "How an Archeologist Works". Scientific American. Vol. 149, no. 6. p. 261. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1233-261.

- — (1933). "The Campaign of 1934". Hesperia. 4 (3): 340–370. JSTOR 146457.

- — (1933). "The Current Excavations in the Athenian Agora". American Journal of Archaeology. 37 (2): 305–312. JSTOR 498448.

- — (1933). "The Sculpture". Hesperia. 2 (4): 514–541. JSTOR 146656.

- — (1933). "The Conclusion of the 1936 Campaign in the Athenian Agora". American Journal of Archaeology. 40 (4): 403–414. JSTOR 498793.

- — (1936). "The Current Excavations in the Athenian Agora". American Journal of Archaeology. 40 (2): 188–203. JSTOR 498475.

- — (1937). "The Campaign of 1936". Hesperia. 6 (3): 333–381. JSTOR 146646.

- — (1937). "The Campaign of 1937". Hesperia. 7 (3): 311–362. JSTOR 146578.

- — (February 1, 1939). "American Archaeologists in Ancient Athens". Scientific American. Vol. 160, no. 2. p. 90. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0239-90. JSTOR 24955537.

- — (August 1, 1939). "Excavations in Ancient Athens". Scientific American. Vol. 151, no. 4. p. 181. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1034-181.

- — (1939). "The Campaign of 1938". Hesperia. 8 (3): 201–246. JSTOR 146675.

- — (1940). "The Campaign of 1939". Hesperia. 9 (3): 261–308. JSTOR 146481.

Footnotes

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The excavations had begun in 1896, but been paused between 1915 and 1925.[16]

- ^ Lord lists Shear among Hill's "many pupils", though Shear was never formally his student.[19]

- ^ Shear considered that the original phases of the building predated the Roman capture and destruction of Corinth in 146 BCE, and that it was rebuilt after 46 BCE and used throughout the ensuing Roman period.[22]

- ^ Lord gives the date of this work as 1926,[26] Kourelis gives 1927.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Stillwell 1945, p. 582.

- ^ a b c Shear 1904, "Life".

- ^ The Princeton Alumni Weekly, October 4, 1916, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Hood 1998, p. 2010.

- ^ a b c de Grummond 1996, p. 1027.

- ^ a b c d Hood 1998, p. 175.

- ^ Hood 1998, p. 174. For the nature of the excavations, see Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, 1911, p. xiv–xv.

- ^ Hood 1998, p. 174. For the dates of the Sardis excavations, see Luke 2019, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hood 1998, p. 174.

- ^ a b Stillwell 1945, p. 583.

- ^ Hood 1998, p. 174. For the date of the surrender, see Smith 2008, p. xiv.

- ^ Stillwell 1945, pp. 582–583.

- ^ Blegen 1922, p. 4 (for the details of the discovery); Lord 1947, p. 148; Hood 1998, p. 174 (for the details of the site).

- ^ Meritt 1984, p. 216.

- ^ Lord 1947, p. 148.

- ^ Williams 2003, p. vii; Hoskins Walbank & Walbank 2015, p. 149.

- ^ Lord 1947, p. 172.

- ^ Hill 1926, p. 13.

- ^ Lord 1947, p. 191.

- ^ Lord 1947, p. 183.

- ^ Shear 1930, p. 15.

- ^ Shear 1930, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Hoskins Walbank & Walbank 2015, p. 150.

- ^ Lord 1947, p. 186.

- ^ Lord 1947, p. 187.

- ^ Lord 1947, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Kourelis 2007, p. 397.

- ^ Hood 1998, p. 174; Kourelis 2007, p. 397.

- ^ Lord 1947, p. 195.

- ^ Shear 1930, Dedication.

- ^ Lord 1947, p. 208.

- ^ Lord 1947, p. 212. On de Waele, see Vogeikoff-Brogan 2021.

- ^ Lord 1947, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Lord 1947, pp. 215, 220.

- ^ Lord 1947, p. 202.

- ^ Hoff 1996, p. 45.

- ^ Lord 1947, p. 232.

- ^ Lord 1947, pp. 220–221.

- ^ a b Lord 1947, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Lord 1947, p. 234.

- ^ Lord 1947, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Lord 1947, pp. 202, 231.

- ^ Commemorative Studies in Honor of Theodore Leslie Shear, 1949, preface

- ^ Cook 1950, p. 89.

- ^ Lord 1947, p. 235.

- ^ Hood 1998, pp. 175–176.

Works cited

[edit]- Blegen, Carl W. (April 5, 1922), Report on Excavations at Zygouries, Hagiorgitika and Hymettus (PDF), Athens – via American School of Classical Studies at Athens

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Commemorative Studies in Honor of Theodore Leslie Shear (PDF). Hesperia Supplements. Vol. 8. Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 1949. ISBN 978-0-87661-508-9.

- Cook, John Manuel (1950). "Review: Commemorative Studies in Honor of Theodore Leslie Shear (Hesperia, Supplement VIII)". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 70: 89–90. doi:10.2307/629320.

- de Grummond, Nancy (1996). "Shear, T. Leslie (1880–1945)". In de Grummond, Nancy (ed.). An Encyclopaedia of the History of Classical Archaeology. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 1026–1027. ISBN 1-884964 80 X.

- "Dr. William McDowell Halsey '71". The Princeton Alumni Weekly. 17 (1): 28. October 4, 1916.

- Hill, Bert Hodge (1926), Forty-Fifth Annual Report of the Managing Committee of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (PDF) – via American School of Classical Studies at Athens

- Hoff, Michael (1996). "American School of Classical Studies at Athens". In de Grummond, Nancy (ed.). An Encyclopaedia of the History of Classical Archaeology. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 44–45. ISBN 1-884964 80 X.

- Hood, Rachel (1998). Faces of Archaeology in Greece: Caricatures by Piet de Jong. Oxford: Leopard's Head. ISBN 0-904920-38-0.

- Hoskins Walbank, Mary E.; Walbank, Michael B. (2015). "A Roman Corinthian Family Tomb and Its Afterlife". Hesperia. 84 (1): 149–206. JSTOR 10.2972/hesperia.84.1.0149.

- Lord, Louis E. (1947). A History of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 1882–1942 (PDF). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC 648555. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- Luke, Christina (2019). A Pearl in Peril: Heritage and Diplomacy in Turkey. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-049887-0.

- Kourelis, Kostis (2007). "Byzantium and the Avant-Garde: Excavations at Corinth, 1920s–1930s". Hesperia. 76 (2): 391–442. doi:10.2972/hesp.76.2.391. ISSN 0018-098X. JSTOR 25068026. S2CID 162303616.

- Meritt, Lucy Shoe (1984). History of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 1939–1980. Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens. ISBN 0-87661-942-1.

- "Proceedings of the Forty-Third Annual Meeting of the American Philological Association Held at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, December, 1911 Also of the Thirteenth Annual Meeting of the Philological Association of the Pacific Coast Held at San Francisco, California November, 1911". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 42: i–iii, v–cxvii. 1911. JSTOR 282581.

- Smith, Peter C. (2008). War in the Aegean: The Campaign for the Eastern Mediterranean in World War II. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-4637-3.

- Stillwell, Richard (1945). "Necrology: Theodore Leslie Shear". American Journal of Archaeology. 49 (4): 582–583. JSTOR 499873.

- Williams, Charles Kaufmann, II (2003). "Preface". Corinth: The Centenary: 1896–1996. Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens. pp. vii–ix. ISBN 0-87661-020-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Vogeikoff-Brogan, Natalia (February 7, 2021). "Where There's Smoke There's Fire: De Waele's Story". From the Archivist's Notebook. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 25, 2025.