User:Iamojo/testcase/EasterIslandShort

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{langx}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (April 2022) |

Easter Island

Rapa Nui (Rapa Nui) Isla de Pascua (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

Outer slope of the Rano Raraku volcano, the quarry of the Moais with many uncompleted statues. | |

| |

| Coordinates: 27°7′S 109°22′W / 27.117°S 109.367°W | |

| Country | Chile |

| Region | Valparaíso |

| Province | Isla de Pascua |

| Commune | Isla de Pascua |

| Seat | Hanga Roa |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Body | Municipal council |

| • Provincial Governor | Laura Alarcón Rapu (IND) |

| • Alcalde | Pedro Edmunds Paoa (PRO) |

| Area | |

• Total | 163.6 km2 (63.2 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 507 m (1,663 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2017 census) | |

• Total | 7,750[1] |

| • Density | 47/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (EAST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (EASST) |

| Country Code | +56 |

| Currency | Peso (CLP) |

| Language | Spanish, Rapa Nui |

| Driving side | right |

| NGA UFI=-905269 | |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Moai at Rano Raraku, Easter Island | |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, v |

| Reference | 715 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th Session) |

| Area | 6,666 ha |

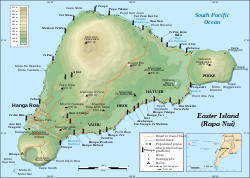

Easter Island (Rapa Nui; Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, called moai, which were created by the early Rapa Nui people. In 1995, UNESCO named Easter Island a World Heritage Site, with much of the island protected within Rapa Nui National Park.

| Climate data for Easter Island (Mataveri International Airport) 1991–2020, extremes 1912–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.0 (89.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

31.0 (87.8) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

33.0 (91.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.0 (93.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 26.9 (80.4) |

27.5 (81.5) |

26.9 (80.4) |

25.5 (77.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.5 (74.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.6 (74.5) |

22.4 (72.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.4 (66.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.7 (60.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

18.7 (65.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12.0 (53.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

8.2 (46.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

8.0 (46.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

9.7 (49.5) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 81.3 (3.20) |

69.3 (2.73) |

86.9 (3.42) |

123.0 (4.84) |

116.9 (4.60) |

109.2 (4.30) |

113.1 (4.45) |

97.1 (3.82) |

97.3 (3.83) |

90.9 (3.58) |

75.2 (2.96) |

69.6 (2.74) |

1,129.8 (44.48) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.1 | 9.6 | 10.7 | 11.6 | 12.0 | 12.3 | 11.6 | 10.6 | 10.2 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 9.0 | 126.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77 | 79 | 79 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 80 | 79 | 77 | 77 | 78 | 79 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 271.7 | 255.6 | 238.7 | 199.9 | 175.9 | 148.3 | 162.4 | 177.2 | 180.3 | 213.6 | 219.9 | 251.0 | 2,494.5 |

| Source 1: Dirección Meteorológica de Chile (extremes 1954–present)[3][4] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (precipitation days 1991–2020),[5] Deutscher Wetterdienst (extremes 1912–1990 and humidity)[6] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

[edit]Easter Island, together with its closest neighbour, the tiny island of Isla Salas y Gómez 415 km (258 mi) farther east, is recognized by ecologists as a distinct ecoregion, the Rapa Nui subtropical broadleaf forests. The original subtropical moist broadleaf forests are now gone, but paleobotanical studies of fossil pollen, tree moulds left by lava flows, and root casts found in local soils indicate that the island was formerly forested, with a range of trees, shrubs, ferns, and grasses. A large extinct palm, Paschalococos disperta, related to the Chilean wine palm (Jubaea chilensis), was one of the dominant trees as attested by fossil evidence. Like its Chilean counterpart it probably took close to 100 years to reach adult height. The Polynesian rat, which the original settlers brought with them, played a very important role in the disappearance of the Rapa Nui palm. Although some may believe that rats played a major role in the degradation of the forest, less than 10% of palm nuts show teeth marks from rats. The remains of palm stumps in different places indicate that humans caused the trees to fall because in large areas, the stumps were cut efficiently.[7]

Culture

[edit]

Mythology

[edit]The most important myths are:[citation needed]

- Tangata manu, the Birdman cult which was practised until the 1860s.

- Makemake, an important god.

- Aku-aku, the guardians of the sacred family caves.

- Moai-kava-kava a ghost man of the Hanau epe (long-ears.)

- Hekai ite umu pare haonga takapu Hanau epe kai noruego, the sacred chant to appease the aku-aku before entering a family cave.

Stone work

[edit]The Rapa Nui people had a Stone Age culture and made extensive use of local stone:

- Basalt, a hard, dense stone used for toki and at least one of the moai.

- Obsidian, a volcanic glass with sharp edges used for sharp-edged implements such as Mataa and for the black pupils of the eyes of the moai.

- Red scoria from Puna Pau, a very light red stone used for the pukao and a few moai.

- Tuff from Rano Raraku, a much more easily worked rock than basalt that was used for most of the moai.

Moai (statues)

[edit]The large stone statues, or moai, for which Easter Island is famous, were carved in the period 1100–1680 CE (rectified radio-carbon dates).[8] A total of 887 monolithic stone statues have been inventoried on the island and in museum collections.[9] Although often identified as "Easter Island heads", the statues have torsos, most of them ending at the top of the thighs; a small number are complete figures that kneel on bent knees with their hands over their stomachs.[10][11] Some upright moai have become buried up to their necks by shifting soils.

Ahu (stone platforms)

[edit]

Ahu are stone platforms. Varying greatly in layout, many were reworked during or after the huri mo'ai or statue-toppling era; many became ossuaries, one was dynamited open, and Ahu Tongariki was swept inland by a tsunami. Of the 313 known ahu, 125 carried moai – usually just one, probably because of the shortness of the moai period and transportation difficulties. Ahu Tongariki, one km (0.62 mi) from Rano Raraku, had the most and tallest moai, 15 in total.[12] Other notable ahu with moai are Ahu Akivi, restored in 1960 by William Mulloy, Nau Nau at Anakena and Tahai. Some moai may have been made from wood and were lost.

The classic elements of ahu design are:

- A retaining rear wall several feet high, usually facing the sea

- A front wall made of rectangular basalt slabs called paenga

- A fascia made of red scoria that went over the front wall (platforms built after 1300)

- A sloping ramp in the inland part of the platform, extending outward like wings

- A pavement of even-sized, round water-worn stones called poro

- An alignment of stones before the ramp

- A paved plaza before the ahu. This was called marae

- Inside the ahu was a fill of rubble.

On top of many ahu would have been:

- Moai on squarish "pedestals" looking inland, the ramp with the poro before them.

- Pukao or Hau Hiti Rau on the moai heads (platforms built after 1300).

- When a ceremony took place, "eyes" were placed on the statues. The whites of the eyes were made of coral, the iris was made of obsidian or red scoria.

Ahu evolved from the traditional Polynesian marae. In this context, ahu referred to a small structure sometimes covered with a thatched roof where sacred objects, including statues, were stored. The ahu were usually adjacent to the marae or main central court where ceremonies took place, though on Easter Island, ahu and moai evolved to much greater size. There the marae is the unpaved plaza before the ahu. The biggest ahu is 220 m (720 ft) and holds 15 statues, some of which are 9 m (30 ft) high. The filling of an ahu was sourced locally (apart from broken, old moai, fragments of which have been used in the fill).[13] Individual stones are mostly far smaller than the moai, so less work was needed to transport the raw material, but artificially leveling the terrain for the plaza and filling the ahu was laborious.

Stone walls

[edit]One of the highest-quality examples of Easter Island stone masonry is the rear wall of the ahu at Vinapu. Made without mortar by shaping hard basalt rocks of up to 7,000 kg (6.9 long tons; 7.7 short tons) to match each other exactly, it has a superficial similarity to some Inca stone walls in South America.[14]

Stone houses

[edit]Two types of houses are known from the past: hare paenga, a house with an elliptical foundation, made with basalt slabs and covered with a thatched roof that resembled an overturned boat, and hare oka, a round stone structure. Related stone structures called Tupa look very similar to the hare oka, except that the Tupa were inhabited by astronomer-priests and located near the coast, where the movements of the stars could be easily observed. Settlements also contain hare moa ("chicken house"), oblong stone structures that housed chickens. The houses at the ceremonial village of Orongo are unique in that they are shaped like hare paenga but are made entirely of flat basalt slabs found inside Rano Kao crater. The entrances to all the houses are very low, and entry requires crawling.

In early times the people of Rapa Nui reportedly sent the dead out to sea in small funerary canoes, as did their Polynesian counterparts on other islands. They later started burying people in secret caves to save the bones from desecration by enemies. During the turmoil of the late 18th century, the islanders seem to have started to bury their dead in the space between the belly of a fallen moai and the front wall of the structure. During the time of the epidemics they made mass graves that were semi-pyramidal stone structures.

Petroglyphs

[edit]Easter Island has one of the richest collections of petroglyphs in all Polynesia. Around 1,000 sites with more than 4,000 petroglyphs are catalogued. Designs and images were carved out of rock for a variety of reasons: to create totems, to mark territory, or to memorialize a person or event. There are distinct variations around the island in the frequency of themes among petroglyphs, with a concentration of Birdmen at Orongo. Other subjects include sea turtles, Komari (vulvas) and Makemake, the chief god of the Tangata manu or Birdman cult.[15]

- Petroglyphs

-

Fish petroglyph found near Ahu Tongariki

Caves

[edit]The island[16] and neighbouring Motu Nui are riddled with caves, many of which show signs of past human use for planting and as fortifications, including narrowed entrances and crawl spaces with ambush points. Many caves feature in the myths and legends of the Rapa Nui.[17]

Other stones

[edit]The Pu o Hiro or Hiro's Trumpet is a stone on the north coast of Easter Island. It was once a musical instrument used in fertility rituals.[18][19][20]

Rongorongo

[edit]Easter Island once had an apparent script called rongorongo. Glyphs include pictographic and geometric shapes; the texts were incised in wood in reverse boustrophedon direction. It was first reported by French missionary Eugène Eyraud in 1864. At that time, several islanders said they could understand the writing, but according to tradition, only ruling families and priests were ever literate, and none survived the slave raids and subsequent epidemics. Despite numerous attempts, the surviving texts have not been deciphered, and without decipherment it is not certain that they are actually writing. Part of the problem is the small amount that has survived: only two dozen texts, none of which remain on the island. There are also only a couple of similarities with the petroglyphs on the island.[21]

Wood carving

[edit] |

|

| Skeletal statuette | Atypical portly statuette |

Wood was scarce on Easter Island during the 18th and 19th centuries, but a number of highly detailed and distinctive carvings have found their way to the world's museums. Particular forms include:[22]

- Reimiro, a gorget or breast ornament of crescent shape with a head at one or both tips.[23] The same design appears on the flag of Rapa Nui. Two Rei Miru at the British Museum are inscribed with Rongorongo.

- Moko Miro, a man with a lizard head. The Moko Miro was used as a club because of the legs, which formed a handle shape. If it was not held by hand, dancers wore it around their necks during feasts. The Moko Miro would also be placed at the doorway to protect the household from harm. It would be hanging from the roof or set in the ground. The original form had eyes made from white shells, and the pupils were made of obsidian.[24]

- Moai kavakava are male carvings and the Moai Paepae are female carvings.[25] These grotesque and highly detailed human figures carved from Toromiro pine, represent ancestors. Sometimes these statues were used for fertility rites. Usually, they are used for harvest celebrations; "the first picking of fruits was heaped around them as offerings". When the statues were not used, they would be wrapped in bark cloth and kept at home. There were a few times that are reported when the islanders would pick up the figures like dolls and dance with them.[25] The earlier figures are rare and generally depict a male figure with an emaciated body and a goatee. The figures' ribs and vertebrae are exposed and many examples show carved glyphs on various parts of the body but more specifically, on the top of the head. The female figures, rarer than the males, depict the body as flat and often with the female's hand lying across the body. The figures, although some were quite large, were worn as ornamental pieces around a tribesman's neck. The more figures worn, the more important the man. The figures have a shiny patina developed from constant handling and contact with human skin.[citation needed]

- Ao, a large dancing paddle

21st-century culture

[edit]The Rapanui sponsor an annual festival, the Tapati, held since 1975 around the beginning of February to celebrate Rapa Nui culture. The islanders also maintain a national football team and three discos in the town of Hanga Roa. Other cultural activities include a musical tradition that combines South American and Polynesian influences and woodcarving.

Sports

[edit]The Chilean leg of the Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series takes place on the Island of Rapa Nui.

Tapati Festival

[edit]Tapati Rapa Nui festival ("week festival" in the local language) is an annual two-week long festival celebrating Easter Island culture.[26] The Tapati is centered around a competition between two families/ clans competing in various competitions to earn points. The winning team has their candidate crowned 'queen' of the island for the next year. The competitions are a way to maintain and celebrate traditional cultural activities such as cooking, jewelry-making, woodcarving, and canoeing.[27]

Demographics

[edit]2012 census

[edit]Population at the 2012 census was 5,761 (increased from 3,791 in 2002).[28] In 2002, 60% were persons of indigenous Rapa Nui origin, 39% were mainland Chileans (or their Easter Island-born descendants) of European (mostly Spanish) or mestizo (mixed European and indigenous Chilean Amerindian) origin and Easter Island-born mestizos of European and Rapa Nui and/or native Chilean descent, and the remaining 1% were indigenous mainland Chilean Amerindians (or their Easter Island-born descendants).[29] As of 2012[update], the population density on Easter Island was 35/km2 (91/sq mi).

Demographic history

[edit]The 1982 population was 1,936. The increase in population in the last census was partly caused by the arrival of people of European or mixed European and Native American descent from the Chilean mainland. However, most married a Rapa Nui spouse. Around 70% of the population were natives. Estimates of the pre-European population range from 7–17,000. Easter Island's all-time low of 111 inhabitants was reported in 1877. Out of these 111 Rapa Nui, only 36 had descendants, and all of today's Rapa Nui claim descent from those 36.

Languages

[edit]Easter Island's traditional language is Rapa Nui, an Eastern Polynesian language, sharing some similarities with Hawaiian and Tahitian. However, as in the rest of mainland Chile, the official language used is Spanish. Easter Island is the only territory in Polynesia where Spanish is an official language.

It is supposed[30] that the 2,700 indigenous Rapa Nui living in the island have a certain degree of knowledge of their traditional language; however, census data does not exist on the primary known and spoken languages among Easter Island's inhabitants and there are recent claims that the number of fluent speakers is as low as 800.[31] Indeed, Rapa Nui has been declining in its number of speakers as the island undergoes Hispanicization, because the island is under the jurisdiction of Chile and is now home to a number of Chilean continentals, most of whom speak only Spanish. For this reason, most Rapa Nui children now grow up speaking Spanish, and those who do learn Rapa Nui begin learning it later in life.[32] Even with efforts to revitalize the language,[33] Ethnologue has established that Rapa Nui is currently a threatened language.[30]

Easter Island's indigenous Rapa Nui toponymy has survived with few Spanish additions or replacements, a fact that has been attributed in part to the survival of the Rapa Nui language.[34]

Administration and legal status

[edit]Easter Island shares with Juan Fernández Islands the constitutional status of "special territory" of Chile, granted in 2007. As of 2011[update] a special charter for the island was under discussion in the Chilean Congress.

Administratively, the island is a province (Isla de Pascua Province) of the Valparaíso Region and contains a single commune (comuna) (Isla de Pascua). Both the province and the commune are called Isla de Pascua and encompass the whole island and its surrounding islets and rocks, plus Isla Salas y Gómez, some 380 km (240 mi) to the east. The provincial governor is appointed by the President of the Republic.[35] The municipal administration is located in Hanga Roa, led by a mayor and a six-member municipal council, all directly elected for a four-year mandate.

Notable people

[edit]

- Laura Alarcón Rapu, governor (since 2018)

- Tiare Aguilera Hey, member of the Chilean Constitutional Convention (since 2021)

- Felipe González de Ahedo (1714–1802), a Spanish navigator and cartographer; annexed Easter Island in 1770.

- Angata (c. 1853–1914), native catechist and prophetess who led a 1914 rebellion

- Thomas Barthel (1923–1997) a German ethnologist and epigrapher

- Carmen Cardinali (born 1944) a Rapa Nui Chilean professor, governor of Easter Island, 2010-2014.

- Jean-Baptiste Dutrou-Bornier (1834–1876) a French mariner, removed many of the Rapa Nui people and turned the island into a sheep ranch.

- Sebastian Englert (1888–1969), missionary and ethnologist

- Eugène Eyraud (1820–1868), missionary

- Thor Heyerdahl (1914–2002), a Norwegian adventurer and ethnographer

- Melania Hotu (born 1959), governor (2006–2010, 2015–2018)

- Marta Hotus Tuki (born 1969), governor (2014–2015)

- Riro Kāinga (died 1898 or 1899), last person to hold title of king and rule before Chilean consolidation

- Kings of Easter Island

- Hotu Matuꞌa, island founder

- William Mulloy (1917–1978), an American anthropologist and archaeologist

- Nga'ara (died 1859), one of the last ‘ariki

- Jacobo Hey Paoa, first Rapa Nui male to earn a law degree and become an attorney

- Pedro Edmunds Paoa (born 1961), mayor and former governor

- Juan Edmunds Rapahango (1923–2012), former mayor

- Hippolyte Roussel (1824–1898), a French priest and missionary

- Katherine Routledge (1866–1935), an English archaeologist and anthropologist

- Alexander Ariʻipaea Salmon (1855–1914) English-Jewish-Tahitian de facto ruler of Easter Island, 1878-1888.

- Mahani Teave (born 1983), a Chilean American classical pianist

- Atamu Tekena (c. 1850–1892), missionary installed King who ceded island to Chile

- José Fati Tepano, first Rapa Nui male to serve as a titular judge upon completing training in Chile

- Juan Tepano (1867–1947), indigenous leader and cultural informant

- Valentino Riroroko Tuki (1932–2017) last claimant to the Rapa Nui throne

- Lynn Rapu Tuki (born 1969), head-teacher, promotes the arts and traditions of the Rapa Nui People.

- Luz Zasso Paoa a Rapa Nui politician, mayor of Easter Island, 2008-2012.

Transportation

[edit]Easter Island is served by Mataveri International Airport, with jet service (currently Boeing 787s) from LATAM Chile and, seasonally, subsidiaries such as LATAM Perú.

Gallery

[edit]-

Hanga Roa town hall

-

Polynesian dancing with feather costumes is on the tourist itinerary.

-

Fishing boats

-

Front view of the Catholic Church, Hanga Roa

-

Interior view of the Catholic Church in Hanga Roa

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Censo 2017". National Statistics Institute (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Censo de Población y Vivienda 2002". National Statistics Institute. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Datos Normales y Promedios Históricos Promedios de 30 años o menos" (in Spanish). Dirección Meteorológica de Chile. Archived from the original on 21 May 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ "Temperatura Histórica de la Estación Chacalluta, Arica Ap. (180005)" (in Spanish). Dirección Meteorológica de Chile. Archived from the original on 21 May 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ "Isla de Pascua Climate Normals 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 6 August 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Mataveri / Osterinsel (Isla de Pascua) / Chile" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ Mieth, A.; Bork, H. R. (2010). "Humans, climate or introduced rats – which is to blame for the woodland destruction on prehistoric Rapa Nui (Easter Island)?". Journal of Archaeological Science. 37 (2): 417. Bibcode:2010JArSc..37..417M. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2009.10.006.

- ^ Beck, J. Warren (2003), "Mata Ki Te Rangi: Eyes towards the Heavens", Easter Island: Scientific Exploration into the World's Environmental Problems in Microcosm, Springer, p. 100, ISBN 978-0306474941, archived from the original on 12 April 2016, retrieved 27 March 2013

- ^ Jo Anne van Tilburg (6 May 2009). "What is the Easter Island Statue Project?". Easter Island Statue Project. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Skjølsvold, Arne "Report 14: The Stone Statues and Quarries of Rano Raraku in Thor Heyerdahl and Edwin N. Ferdon Jr. (eds.) 'Reports of the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island and the East Pacific'", Volume 1, Archaeology of Easter Island, Monographs of the School of American Research and The Museum of New Mexico, Number 24, Part 1, 1961, pp. 339–379. (esp. p. 346 for the description of the general statues and Fig. 91, p. 347, pp. 360–362 for the description of the kneeling statues)

- ^ Van Tilburg, Jo Anne. Easter Island. Archaeology, Ecology and Culture, British Museum Press 1994:134–135, fig. 106

- ^ Diamond 2005, p. 80.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Heyerdahl 1961was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Heyerdahl 1961 However, Alfred Metraux pointed out that the rubble-filled Rapanui walls were a fundamentally different design to those of the Inca, as these are trapezoidal in shape as opposed to the perfectly fitted rectangular stones of the Inca. See also "this FAQ". Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Lee 1992

- ^ "The Easter Island Caves: an underground world". Nayara Hangaroa. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ "Private Tour: Easter Island Caves | Chile Activities". Lonely Planet.

- ^ "Easter Island musical stone went from priceless to worthless / Boing Boing". boingboing.net. 21 March 2018. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ "Pu o Hiro (Hiro's Trumpet) – Easter Island, Chile". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ "Pu O Hiro – Die Trompete des Hiro". osterinsel.de. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Fischer, pp. 31, 63.

- ^ Routledge 1919, p. 268

- ^ Wooden gorget (rei miro) Archived 18 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. British Museum.

- ^ Brooklyn Museum, "Collections: Arts of the Pacific Islands: Lizard Figure (Moko Miro)." Archived 2 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine Last modified 2011.

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica Online, "Moai Figure" Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Tapati Rapa Nui festival". Easterisland.travel. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Ian, James (20 October 2018). "Easter Island: More Than Just Statues – Tapati Festival on Rapa Nui". Travel Collecting. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Primeros datos del Censo: Hay 37.626 mujeres más que hombres en la V Región Archived 16 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Estrellavalpo.cl (11 June 2002). Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ "Censo 2002". Ine.cl. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Rapa Nui". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ Fischer 2008: p. 149

- ^ Makihara 2005a: p. 728

- ^ "Gobernación Provincial Isla de Pascua". Gobernación Provincial Isla de Pascua. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ Latorre 2001: p. 129

- ^ "Territorial division of Chile" (PDF) (in Spanish). National Statistics Institute. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

Bibliography

[edit]- Diamond, Jared (2005). Collapse. How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0143036555.

- Fischer, Steven Roger (1995). "Preliminary Evidence for Cosmogonic Texts in Rapanui's Rongorongo Inscriptions". Journal of the Polynesian Society (104): 303–21.

- Fischer, Steven Roger (1997). Glyph-breaker: A Decipherer's Story. New York: Copernicus/Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-1-4612-2298-9.

- Fischer, Steven Roger (1997). RongoRongo, the Easter Island Script: History, Traditions, Texts. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198237105.

- Heyerdahl, Thor (1961). Thor Heyerdahl; Edwin N. Ferdon Jr. (eds.). The Concept of Rongorongo Among the Historic Population of Easter Island. Stockholm: Forum.

- Heyerdahl, Thor (1958). Aku-Aku; The 1958 Expedition to Easter Island. Chicago, Rand McNally.

- McLaughlin, Shawn (2007). The Complete Guide to Easter Island. Los Osos: Easter Island Foundation. ISBN 978-1880636251.

- Metraux, Alfred (1940). "Ethnology of Easter Island". Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin (160). ISBN 9780527022686.

- Pinart, Alphonse (1877). "Voyage à l'Ile de Pâques (Océan Pacifique)". Le Tour du Monde; Nouveau Journal des Voyags. 36: 225.

- Routledge, Katherine (1919). The Mystery of Easter Island. The story of an expedition. London. ISBN 978-0404142315.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Steadman, David (2006). Extinction and Biogeography in Tropical Pacific Birds. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226771427.

Further reading

[edit]- Altman, Ann M. (2004). Early Visitors to Easter Island 1864–1877 (translations of the accounts of Eugène Eyraud, Hippolyte Roussel, Pierre Loti and Alphonse Pinart; with an Introduction by Georgia Lee). Los Osos: Easter Island Foundation.

- Boersema, Jan J. (13 April 2015). The Survival of Easter Island: Dwindling Resources and Cultural Resilience. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-29845-9.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 834.

- Englert, Sebastian F. (1970). Island at the Center of the World. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Erickson, Jon D.; Gowdy, John M. (2000). "Resource Use, Institutions, and Sustainability: A Tale of Two Pacific Island Cultures". Land Economics. 76 (3): 345–54. doi:10.2307/3147033. JSTOR 3147033.

- Kjellgren, Eric (2001). Splendid isolation: art of Easter Island. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1588390110.

- Lee, Georgia (1992). The Rock Art of Easter Island. Symbols of Power, Prayers to the Gods. Los Angeles: The Institute of Archaeology Publications. ISBN 978-0917956744.

- Pendleton, Steve; Maddock, David (2014). Collecting Easter Island – Stamps and Postal History. London: Pacific Islands Study Circle. ISBN 978-1899833221.

- Shepardson, Britton (2013). Moai: a New Look at Old Faces. Santiago: Rapa Nui Press. ISBN 978-9569337000.

- Thomson, William J. (1891). "Te Pito te Henua, or Easter Island. Report of the United States National Museum for the Year Ending June 30, 1889". Annual Reports of the Smithsonian Institution for 1889: 447–552.in Internet Archive

- van Tilburg, Jo Anne (1994). Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-0714125046.

- Vergano, Dan (15 November 2009). "Were rats behind Easter Island mystery?". USA Today.

External links

[edit]- Terevaka Archaeological Outreach (TAO) – Non-profit Educational Outreach & Cultural Awareness on Easter Island

- Easter Island – The Statues and Rock Art of Rapa Nui – Bradshaw Foundation / Dr Georgia Lee

- Chile Cultural Society – Easter Island

- Rapa Nui Digital Media Archive – Creative Commons – licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas, focused in the area around Rano Raraku and Ahu Te Pito Kura with data from an Autodesk/CyArk research partnership

- Mystery of Easter Island – PBS Nova program

- Current Archaeology's comprehensive description of island and discussion of dating controversies Archived 10 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Books and Texts about Easter Island from the Internet Archive

- History of Easter Island illustrated by stamps

- Dunning, Brian (12 April 2022). "Skeptoid #827: What Really Happened on Easter Island". Skeptoid. Retrieved 14 May 2022.