User:Hawkeye7/Sandbox2

The Manhattan Project feed materials program located and procured uranium ores, and refined and processed them into feed materials for use in the Manhattan Project's isotope enrichment plants at the Clinton Engineer Works in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and its nuclear reactors at the Hanford Engineer Works in Washington state.

The original goal of the feed materials program in 1942 was to acquire approximately 1,500 tonnes (1,700 short tons) of triuranium octoxide (U3O8) (black oxide). By the time of the dissolution of the Manhattan District on 1 January 1947, it had acquired about 9,100 tonnes (10,000 short tons), 72% of which came from the Belgian Congo, 14% from the Colorado Plateau, and 9% from Canada. An additional 5% came from "miscellaneous sources", which included quantities recovered from Europe by the Manhattan Project's Alsos Mission.

Ores from the Belgian Congo contained the most uranium per mass of rock by far. Much of the mined ore from the Shinkolobwe mine had a uranium dioxide (UO2) content as high as 65% to 75%, which was many times higher than any other global sources. In comparison, the Canadian ores could be as rich as 30% uranium dioxide, while American ores, mostly byproducts of the mining of other minerals (especially vanadium), typically contained less than 1% uranium. In 1941, both the Shinkolobwe mine and the Eldorado Mine in Canada were closed and flooded; the Manhattan Project had them reopened and returned to service.

Beyond their immediate wartime needs, the Americans and British governments attempted to control as much of the world's uranium deposits as possible. They created the Combined Development Trust in June 1944, with the director of the Manhattan Project, Major General Leslie R. Groves Jr. as its chairman. The Combined Development Trust procured uranium and thorium ores on international markets. A special account not subject to the usual auditing and controls was used to hold Trust monies. Between 1944 and his resignation from the Trust in 1947, Groves deposited a total of $37.5 million (equivalent to $669.83 million in 2024). In 1944, the Combined Development Trust purchased 3,440,000 pounds (1,560,000 kg) of uranium oxide ore from the Belgian Congo.

The raw ore was dissolved in nitric acid to produce uranyl nitrate, which was processed into uranium trioxide, which was reduced to highly pure uranium dioxide. By July 1942, Mallinckrodt was producing a ton of highly pure oxide a day, but turning this into uranium metal initially proved more difficult. A branch of the Metallurgical Laboratory was established at Iowa State College in Ames, Iowa, under Frank Spedding to investigate alternatives. This became known as the Ames Project, and the Ames process it developed to produce uranium metal became available in 1943.

Background

[edit]Uranium was discovered in 1789 by the German chemist and pharmacist Martin Heinrich Klaproth, who also established its useful commercial properties, such as its colouring effect on molten glass. It occurs in various ores, notably pitchblende, torbernite, carnotite, and autunite. In the early 19th century it was recovered as a byproduct of mining other ores. Mining of uranium as the principal product began in Joachimsthal in Bohemia in about 1850, at the South Terras mine in Cornwall in 1873, and in Paradox Valley in Colorado in 1898.[1]

-

Torbernite from the Shinkolobwe mine in the Congo

-

Pitchblende from the Czech Republic

-

Carnotite from Uravan District, Colorado, USA

-

Autunite from Spokane County, Washington, USA

A major deposit was found at Shinkolobwe in what was then the Belgian Congo in 1915, and extraction was begun by a Belgian mining company, Union Minière du Haut-Katanga, after the First World War. The high grade of the ore from the mine—65% uranium dioxide (UO2) or more when most sites considered 0.03% to be good—enabled the company to dominate the market. Even the 2,000 tonnes of tailings from the mine considered too poor to bother processing contained up to 20% uranium ore.[2][3][4] Triuranium octoxide) (U3O8), known as black oxide, was mainly used by ceramics industry, which used about 150 tons annually as a colouring agent, and in 1941 sold for US$4.52 per kilogram ($2.05/lb) (equivalent to $96/kg in 2024). Uranium nitrate (UO2(NO3)2) was used by the photographic industry, and sold for US$5.20 per kilogram ($2.36/lb) (equivalent to $111/kg in 2024).[5] The market for uranium was quite small, and by 1937, Union Minière had about 30 years' supply on hand, so the mining and refining operations at Shinkolobwe were terminated.[2]

The discovery of nuclear fission by chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann in December 1938, and its subsequent explanation, verification and naming by physicists Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch, opened up the possibility of uranium becoming an important new source of energy.[6] In nature, uranium has three isotopes: uranium-235, which accounts for 99.28 per cent; uranium-235, which accounts for 0.71 per cent; and uranium-234, which accounts for less than 0.001 per cent.[7] In Britain, in June 1939, Frisch and Rudolf Peierls investigated the critical mass of uranium-235,[8] and found that it was small enough to be carried by contemporary bombers, making an atomic bomb possible. Their March 1940 Frisch–Peierls memorandum initiated the Tube Alloys, the British atomic bomb project.[9]

In June 1942, Colonel James C. Marshall was selected head the Army's part of the American atomic bomb project. He established his headquarters at 270 Broadway in New York City, with Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Nichols became his deputy.[10] Since engineer districts normally carried the name of the city where they were located, Marshall's command was called the Manhattan District. Unlike other engineer districts, though, it had no geographic boundaries, and Marshall had the authority of a division engineer. Over time the entire project became known as "Manhattan".[10] Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves assumed command of the Manhattan Project in September 1942.[11]

One of Groves's first concerns upon taking charge was securing the supply of raw materials, particularly uranium ore.[12] At the time, there was insufficient uranium even for experimental purposes, and no idea how much would ultimately be required.[13] As it turned out, to produce the 60 kg of highly enriched uranium used in the Little Boy bomb required more than 8,300 kg of uranium. The Manhattan Project also pursued the breeding of plutonium for the Fat Man bomb, which used about 6 kg of plutonium. The Manhattan Project's 250 MW production reactors at the Hanford Engineer Works each had a fuel load of 230 tonnes (250 short tons) to breed about 190 grams of plutonium per day.[14]

Organisation

[edit]

Initially, the firm of Stone & Webster made arrangements for the procurement of feed materials, but as the project grew in scope it was decided to have that company concentrate on the design and construction of the Y-12 electromagnetic plant, and arrangements for procurement and refining were handled by Marshall and Nichols.[15]

In October 1942, Marshall established a Materials Section in the Manhattan District headquarters under Lieutenant Colonel Thomas T. Crenshaw Jr., an architect. To assist him, he had Captain Phillip L. Merritt, a geologist, and Captain John R. Ruhoff, a chemical engineer who, as St Louis Area engineer, had worked on uranium metal production.[16][17] Crenshaw became the officer in charge of operations at the Clinton Engineer Works in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, in July 1943, and was succeeded by Ruhoff, who was promoted to lieutenant colonel.[15][18]

The following month, the Manhattan District's headquarters moved to Oak Ridge, but the Materials Section and its successors remained in New York until 1954.[18][19] Nichols, who succeeded Marshall as district engineer on 13 August 1943,[20] felt that this was a better location for it, as it was close to the ports of entry and warehouses for the ores and the headquarters of several of the firms supplying feed materials. He reorganised the section as the Madison Square Area; engineer areas are normally named after their location, and the office was located near Madison Square.[18]

As area engineer, Ruhoff was responsible for nearly four hundred personnel by 1944, of whom three-quarters were in New York. There were two field offices that were responsible for procurement: Murray Hill in New York and Colorado in Grand Junction, Colorado, and five responsible for feed materials processing: Iowa (in Ames, Iowa), St. Louis, Wilmington, Beverly and Tonawanda.[18] Ruhoff was succeeded in October 1944 by Lieutenant Colonel W. E. Kelley, who in turn was succeeded by Lieutenant Colonel G. W. Beeler in April 1946.[15]

The original goal of the feed materials program in 1942 was to acquire approximately 1,500 tonnes (1,700 short tons) of black oxide. By the time of the dissolution of the Manhattan District at the end of 1946, it had acquired about 9,100 tonnes (10,000 short tons). The total cost of the feed materials program up to 1 January 1947 was approximately USD$90,268,490 (equivalent to $1,271,157,917 in 2024), of which $27,592,360 (equivalent to $388,554,709 in 2024) was for procurement of raw materials, $58,622,360 (equivalent to $825,518,151 in 2024) for refining and processing operations, and $3,357,690 (equivalent to $47,282,880 in 2024) for research, development, and quality control.[21]

Procurement

[edit]Africa

[edit]Early activities

[edit]In May 1939, Edgar Sengier, the director of Union Minière, paid a fellow director, Lord Stonehaven, a visit in London. Stonehaven arranged for Sengier to meet with Sir Sir Henry Tizard and Major General Hastings Ismay.[22][23] The Foreign Office had contacted Union Minière and discovered that the company had 59 tonnes (65 short tons) of uranium ore on hand in the UK, and the going price was 6/4 per pound, or £19,000 (equivalent to $1,310,000 in 2023) for the lot. Another 180 tonnes (200 short tons) was in Belgium. Sengier agreed to consider moving this stockpile from Belgium to the UK. In the meantime, the British government purchased a ton of ore from Union Minière's London agents for £709/6/8 (equivalent to $48,928 in 2023).[23] As Sengier left the meeting, Tizard warned him: "Be careful and never forget that you have in your hands something that may mean a catastrophe to your country and mine if this material were to fall into the hands of a possible enemy".[22][12]

The possibility that Belgium might be invaded was taken seriously. In September 1939, Sengier left for New York with authority to conduct business should contact be lost between Belgium and the Congo. Before he departed, he made arrangements for the radium and uranium at the company's refining plant in Olen, Belgium, to be shipped to the Great Britain and the United States. The radium, about 120 grams worth, valued at $1.8 million (equivalent to $40.4 million in 2024) arrived, but 3,200 tonnes (3,500 short tons) of uranium compounds was not shipped before Belgium was overrun by the Germans in May 1940.[24][25]

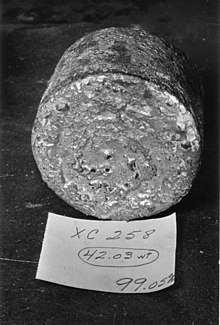

In August 1940, Sengier, fearing a German takeover of the Belgian Congo, ordered some of the stockpile of uranium ore there to be shipped to the United States though Union Minière's subsidiary African Metals Corporation. Some 1,140 tonnes (1,260 short tons) of uranium ore was shipped via Lobito in Angola to New York in two shipments: the first, of 470 tonnes (460 long tons) departed Lobito in September and arrived in New York in November; the second, of 669 tonnes (658 long tons), departed in October and arrived in December.[26][27] The ore was stored in 2,006 steel drums 860 millimetres (34 in) high and 610 millimetres (24 in) in diameter,[28] clearly labelled "uranium ore" and "product of Belgian Congo", in a warehouse at 2351 Richmond Terrace, Port Richmond, Staten Island, belonging to the Archer-Daniels-Midland Company.[27][29]

In March 1942, a few months after the United States belatedly entered Second World War, Sengier was invited to a meeting co-sponsored by the State Department, Metals Reserve Company, Raw Materials Board and the Board of Economic Warfare to discuss non-ferrous metals. He met with Thomas K. Finletter and Herbert Feis, but found them interested only in cobalt and not uranium; the State Department would not be informed of the Manhattan Project until the Yalta Conference in February 1945.[30] At its 9 July meeting, S-1 Executive Committee of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), which was in charge of the American atomic project, saw no immediate need for additional quantities of uranium ore beyond 60 short tons (54 t) it had ordered from the Eldorado Gold Mines Company in Canada. In August, though, it learned that Boris Pregel, an agent for both Union Minière and Eldorado, was seeking to buy 500 short tons (450 t) of Sengier's ore, and he had applied for an export licence to ship it to Eldorado for refining. The S-1 Executive Committee realised that the ore it was paying to be mined and shipped from the Arctic might actually be coming from Staten Island. On 11 September, Vannevar Bush, the head of the OSRD, asked the Army to impose export controls on uranium.[31]

The US Army takes over

[edit]Events began to move swiftly once the Army became involved. On 15 September, Ruhoff secured Sengier's approval for the release of 100 short tons (91 t) or ore, which was shipped to Eldorado's refinery at Port Hope, Ontario, for testing of the oxide content.[32] Nichols met with Sengier in the latter's office at 25 Broadway on 18 September,[27] and the two men reached an eight-sentence agreement that Nichols recorded on a yellow legal pad, giving Sengier a carbon copy. Under this agreement, the United States agreed to purchase the ore in storage on Staten Island and was granted prior rights to purchase the 3,000 short tons (2,700 t) in the Belgian Congo, which would be shipped, stored and refined at the US government's expense. African Metals would retain ownership of the radium in the ore. At a subsequent meeting on 23 September, they agreed on a price: US$1.60 per pound ($3.5/kg) (equivalent to $67/kg in 2024), of which $1.00 would go to African Metals and 60 cents to Eldorado for refining.[33] Sengier opened a special bank account to receive the payments, which the Federal Reserve was instructed to ignore and auditors instructed to accept without question.[34] Contracts were signed on 19 October.[35]

The ore in Staten Island was transferred to the Seneca Ordnance Depot in Romulus, New York, for safe keeping. Meanwhile, arrangements were made to ship the ore from the Belgian Congo. Sengier was of the opinion that it would be safer for the ore to be shipped in fast 30-kilometre-per-hour (16 kn) freighters that could outrun the German U-boats rather than in convoy. This was accepted, and the first shipment, of 250 tonnes (250 long tons), departed on 10 October, followed by a second 20 October and a third on 10 November. Thereafter, ore was shipped at a rate of 410 tonnes (400 long tons) per month from December 1942 through May 1943. Two shipment were lost: one to a U-boat in late 1942, and one due to a maritime accident in early 1943. The ore arrived faster than it could be processed, so it was stored at Seneca.[36][3][37] About 180 tonnes (200 short tons) was lost. Later shipments were temporarily stored at the Clinton Engineer Works. In November 1943, the Middlesex Sampling Plant, a in Middlesex, New Jersey, was leased for the purpose of storage, sampling and assaying. The ore was received in bags and sent for refining as required.[38]

In August 1943, Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt negotiated the Quebec Agreement, which merged the British and American atomic bomb projects,[39][40] and established the Combined Policy Committee to coordinate their efforts.[41] In turn, the Combined Policy Committee created the Combined Development Trust on 13 June 1944 to procure uranium and thorium ores on international markets.[42] Groves was appointed its chairman, with Sir Charles Hambro, the head of the British Raw Materials Mission in Washington, and Frank Lee from the Treasury delegation as the British trustees, and George Bateman, a deputy minister and a member of the Combined Production and Resources Board, representing Canada.[43][44] A special account not subject to the usual auditing and controls was used to hold Trust monies. Between 1944 and his resignation from the Trust at the end of 1947, Groves deposited a total of $37.5 million (equivalent to $669.83 million in 2024).[45]

Post-war

[edit]Groves tried to have the Shinkolobwe mine re-opened and its output sold to the United States.[46] Sengier reported that the mine could yield another 9,100 tonnes (10,000 short tons) of ore containing 50 to 60 per cent oxide, but restarting production required new equipment, electricity to pump out the flooded mine, and assembling a workforce, which would take 18 to 20 months.[47] Mine repairs and dewatering cost about $350,000 and another $200,000 was required to divert electricity away from copper mines.[48] As 30 per cent of the stock in Union Minière were held by British shareholders and the Belgian Government in Exile was in London, the British took the lead in negotiations.[46] Negotiations took much longer than anticipated, but Sir John Anderson and Ambassador John Winant hammered out a deal in May 1944 with with Sengier and the Belgian Government in Exile for the mine to be reopened and 1,720 short tons (1,560 t) of ore to be purchased, and the contract was signed until 25 September 1944.[49]

During the war, all uranium from the Congo had gone to the United States, as had that captured in Europe by the Alsos Mission, even though some of it passed through British hands.[50] The entire output of Shinkolobwe was contracted to the Combined Development Trust until 1956, but in March 1946 there were (unrealised) fears that the mine might be exhausted in 1947, resulting in a severe uranium shortage.[51] After some negotiation, Groves and James Chadwick, the head of the British Mission to the Manhattan Project, agreed on a division of uranium ore production, with everything up to March 1946 going to the United States, and supplies being shared equally thereafter.[50][51] Between VJ-Day and 31 March 1946, ore containing 770 tonnes (850 short tons) of oxide at a cost of USD$2,582,260 (equivalent to $41,637,841 in 2024). Production then picked up as the effect of new machinery was felt, and from 1 April to 1 July 1,786 tonnes (1,969 short tons) of oxide was delivered at a cost of $7,113,956 (equivalent to $114,709,506 in 2024).[52]

At the Combined Policy Committee meeting on 31 July 1946, the financial arrangements were adjusted. Previously, the two countries had split the costs equally; henceforth each would pay for only what they actually received.[50] Britain was therefore able to secure the uranium it needed for High Explosive Research, its own nuclear weapons program, without having to outbid the United States, and paid for it in sterling. Meanwhile, because the adjustment applied retrospectively to VJ-Day, it received reimbursement for the supplies allocated to Britain but given to the United States, thus easing Britain's dollar shortage.[50][53] Although Union Minière would have preferred payment in dollars, it had to accept half in sterling.[52]

By 1 January 1947, when the United States Atomic Energy Commission tool over from the Manhattan Project,[54] approximately 3,501 tonnes (3,859 short tons), of black oxide had been extracted from about 26,974 tonnes (29,734 short tons) of African ore, for which the government paid $9,113,800 (equivalent to $128,340,233 in 2024). In addition, another 2,852 tonnes (3,144 short tons) had been purchased for $9,113,800 (equivalent to $128,340,233 in 2024).[55] Radium-bearing uranium sludge remaining after the refining process remained the property of African Metals and were returned to the company after the war in accordance with the agreement with Sengier. The sludge was packed in wooden barrels and stored at the Clinton Engineer Works and the Middlesex warehouse. Residues from low-grade ores were stored at the Lake Ontario Ordnance Works, which was near the Linde Air Products Company plant where low-grade ores were refined. By 1 January 1947, 18,333 tonnes (20,209 short tons) of sludge was stored there, and 1,492 tonnes (1,645 short tons) had been returned to African Metals.[55]

Canada

[edit]Eldorado mine

[edit]After the Belgian Congo, the next most important source of uranium ore was Canada. Canadian ore came from the Eldorado Mine in the Great Bear Lake area, not far south of the Arctic Circle.[56][57] In May 1930, Gilbert LaBine went prospecting in the area. LaBine was the managing director of Eldorado Gold Mines, a firm he co-founded in January 1926 with his brother Charlie, but which no longer had any gold mines.[58] On 16 May, LaBine found pitchblende near the shores of Echo Bay at a mine site that became Port Radium.[59][60] Eldorado also established a processing plant at Port Hope, Ontario, the only facility of it kind in North America. To run it, LaBine hired Marcel Pochon, a French chemist who had learned how to refine radium under Pierre Curie, who was working at the recently closed South Terras mine in Cornwall.[61][62][63]

Ore was mined at Port Radium and shipped via Great Bear, Mackenzie and Slave Rivers to Waterways, Alberta, and thence by rail to Port Hope.[64][65] Two towboats were acquired: the Radium King and Radium Queen, and they pulled ore scows named Radium One to Radium Twelve.[66][67] Great Bear Lake is only navigable between early July and early October, being icebound the rest of the year,[68] but mining activity continued year-round.[69]

Competition from Union Minière was fierce and served to drive the price of radium down from CDN$70 per milligram in 1930 (equivalent to $1,208 in 2023) to CDN$21 per milligram in 1937 (equivalent to $428 in 2023). Boris Pregel negotiated a cartel deal with Union Minière under which each company gained exclusive access to its home market and split the rest of the world 60:40 in Union Minière's favour. The outbreak of war in September 1939 blocked access to hard-won European markets, especially Germany, a major customer for ceramic-grade uranium. Union Minière lost its refinery at Oolen when Belgium was overrun, forcing it to use Eldorado's mill at Port Hope.[70] With sufficient stocks on hand for five years of operations, Eldorado closed the mine in June 1940.[69][71]

On 15 June 1942, Malcolm MacDonald, the United Kingdom high commissioner to Canada, George Paget Thomson from the University of London and Michael Perrin from Tube Alloys met with Mackenzie King, the Prime Minister of Canada, and briefed him on the atomic bomb project. A subsequent meeting was arranged that same day at which the trio met with C. D. Howe, the Minister for Munitions and Supply and C. J. Mackenzie, the president of the National Research Council Canada. The British had noticed how uranium prices had been rising and feared that Pregel would attempt to corner the market, and they urged that Eldorado be brought under government control. Mackenzie proposed to effect this through secret purchase of the stock.[72] Howe then met with Gilbert LaBine, who agreed to sell his 1,000,303 shares at CDN$1.25 per share (equivalent to $22 in 2023). This was a good deal for LaBine; the stock was trading at 40 cents a share at the time, but the stock only amounted to a quarter of the company's four million shares.[73]

Complex negotiations followed between the Americans, British and Canadians regarding patent rights, export controls, and the exchange of scientific information, but the purchase was approved when Churchill and Roosevelt met at the Second Washington Conference in June 1942.[57] Over the next eighteen months, LaBine and John Proctor from the Imperial Bank of Canada criss-crossed North America buying up stock in Eldorado Gold Mines,[73] which changed its name to the more accurate Eldorado Mining and Refining on 3 June 1943.[69] On 28 January 1944, Howe announced in the House of Commons of Canada that Eldorado had become a crown corporation, and the remaining shareholders would be reimbursed at $1.35 a share.[74]

Production

[edit]

The first order, for 7.3 tonnes (8 short tons) of oxide, was placed with Eldorado by the S-1 Committee in 1941.[75] This was increased to 54 tonnes (60 short tons), of which the committee estimated that 41 tonnes (45 short tons) was required in 1942 for the experimental nuclear reactors at the University of Chicago.[76] Commencing in May 1942, the mill began shipping 14 tonnes (15 short tons) per month. On 16 July, Preger negotiated a deal for the Americans to buy 320 tonnes (350 short tons) at $6.3 per kilogram ($2.85/lb) (equivalent to $110/kg in 2023). Nor was this the end of it: on 22 December, Preger's Canadian Radium and Uranium Corporation placed an order for another 450 tonnes (500 short tons). This meant not only that the mine would be reopened, but that it would be fully occupied with American orders until the end of 1944.[77] The British now became alarmed: they had allowed 18 tonnes (20 short tons) of oxide earmarked for them to be diverted to the Americans, whose need was more pressing, but were now faced with being shut out entirely, with no uranium for the Montreal Laboratory's reactor. The issue was resolved by the Quebec Agreement in August 1943.[78][79]

Ed Bolger, who had been the mine superintendent from 1939 to 1940, led the effort to reactivate the mine in April 1942. He arrived by air with an advance party of 25 and supplies, flown in by Canadian Pacific Air Lines. Some ore had been abandoned on the docks when the mine was closed, and could be shipped immediately, but reactivation was complicated. The mine had filled with water that had to be pumped out, and the water had rotted the timbers. One raise was filled with helium. In order to thaw out the rock, electric heaters were brought in and ventilation was reduced, but this exposed the miner workers to a build up of radon gas. Bolger sought out the richest deposits and worked them first; in one vein, the oxide content was as high as 5%, but monthly production consistently fell short of targets, falling from a high of 73,000 tonnes (80,000 short tons) in August 1943 to 16,741 tonnes (18,454 short tons) in December.[71][80]

Each season, some 1,100 to 1,300 tonnes (1,200 to 1,400 short tons) of freight was delivered to Port Radium by water, along with 2,300 to 2,700 tonnes (2,500 to 3,000 short tons) of oil for the diesel generators from Norman Wells on the Mackenzie River. Shipping supplies by water from Waterways cost $0.11 per kilogram ($0.05/lb) (equivalent to $2/kg in 2023), while air freight from Edmonton cost $1.5 per kilogram ($0.70/lb) (equivalent to $26/kg in 2023).[65] LaBine asked the Americans to expedite the delivery of two new Lockheed Model 18 Lodestar aircraft to Canadian Pacific.[71] United States and Canadian military aircraft were used to move ore from Port Radium to Waterways. In 1943, 270 tonnes (300 short tons) of ore was moved by air.[36] He was also able to get some personnel released from the Canadian armed forces. By 1944, Eldorado had a work force of 230.[71]

By 1 January 1947, the Manhattan District had contracted from Eldorado for 3,755 tonnes (4,139 short tons) of ore concentrates to be delivered as 1,031 tonnes (1,137 short tons) of black oxide at a cost of approximately USD$5,082,300 (equivalent to $71,568,782 in 2024).[69]

United States

[edit]

In the United States, carnotite ores were mined on the Colorado plateau for their vanadium content. The ores contained roughly 1.75% vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) and 0.25% uranium dioxide (UO2). Vanadium was important to the war effort as a hardening agent in steel alloys, and the Metals Reserve Company offered loans and subsidies to increase production. The carnotite sands tailings from this mining activity over the years contained low concentrations that were economically recoverable but uneconomical to ship.[81][56]

The Manhattan District arranged for its suppliers, the Metals Reserve Company, Vanadium Corporation of America (VCA) and the United States Vanadium Corporation (USV), a subsidiary of Union Carbide, to mill tailings that contained 0.25% uranium oxide into concentrates or sludges containing anything from 10% to 50% oxide.[81][56] VCA concentrated its ore at its mill in Naturita, Colorado, before shipment to Vitro's processing plant in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. USV processed tailings at its mill in Uravan, Colorado, for delivery to Linde's plant in Tonawanda. New York. The Manhattan District also contracted with USV to build and operate government-owned mills for processing tailings at Durango, Uravan, and Grand Junction, Colorado.[82]

By 1 January 1947, approximately 344,432 tonnes (379,671 short tons) of ore tailings had been purchased, yielding about 1,224 tonnes (1,349 short tons) of black oxide. Of this, 808 tonnes (891 short tons) came from USV, 210 tonnes (230 short tons) from VCA, 122 tonnes (135 short tons) from the Metals Reserve Company, 24 tonnes (26 short tons) from the Vitro Manufacturing Company and 61 tonnes (67 short tons) from other sources. The total cost of procurement from American sources approximately USD$2,072,330 (equivalent to $29,182,483 in 2024).[81][56]

To conserve uranium, the War Production Board prohibited the sale or purchase of uranium compounds for use in ceramics on 26 January 1943.In August, the use of uranium in the photography was restricted to essential military and industrial applications. The Madison Square Area bought up all available stocks. This amounted to 240 tonnes (270 short tons) of black oxide recoverable from uranium salts, at a cost of USD$1,056,130 (equivalent to $14,872,388 in 2024).[83]

Europe

[edit]The Manhattan Project's Alsos Mission was the Manhattan Project's scientific intelligence mission that operated in Europe. The mission was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Boris Pash, with Samuel Goudsmit as his scientific deputy.[84] In September 1944, the mission secured the corporate headquarters of Union Minière in Antwerp and seized its records.[85] They discovered that over 980 long tons; 1,100 short tons (1,000 t) tons of refined uranium had been sent to Germany, but about 140 tonnes (150 short tons) remained at Olen.[86] They then set out for Olen, where they located 68 tons, but another 80 tons were missing, having been shipped to France in 1940 ahead of the German invasion of Belgium.[87] Groves had it shipped to England, and, ultimately, to the United States.[88]

The Alsos Mission now attempted to recover the shipment that had been sent to France. Documentation was discovered that said that part of it had been sent to Toulouse.[89] An Alsos Mission team under Pash's command reached Toulouse on 1 October and inspected a French Army arsenal. They used a Geiger counter to find barrels containing 31 tons of the uranium from Belgium.[90] The barrels were collected and transported to Marseille, where they were loaded on a ship bound for the United States. During the loading process one barrel fell into the water and had to be retrieved by a Navy diver.[91] The remaining 49 tons of the original shipment to France were never found.[87]

As the Allied armies advanced into Germany in April 1945, Alsos Mission teams searched Stadtilm, where they found documentation concerning the German nuclear program, components of a nuclear reactor, and 7.3 tonnes (8 short tons) of uranium oxide.[92][93] They learned that the uranium ores that had been taken from Belgium in 1944 had been shipped to the Wirtschaftliche Forschungsgesellschaft (WiFO) plant in Staßfurt. This was captured by American troops on 15 April, but it was in the occupation zone allocated to the Soviet Union at the Yalta Conference, so the Alsos Mission, led by Pash, and accompanied by Michael Perrin and Charles Hambro, arrived on 17 April to remove anything of interest. Over the following ten days, 260 truckloads of uranium ore, sodium uranate and ferrouranium weighing about 910 tonnes (1,000 short tons), were retrieved. The uranium was taken to Hildesheim, where most of it was flown to the United Kingdom by the Royal Air Force; the rest was sent to Antwerp by train and loaded onto a ship to England.[94][95][96] In Haigerloch, they found a German experimental nuclear reactor,[97] along with three drums of heavy water and 1.4 tonnes (1.5 short tons) of uranium ingots that were buried in a field.[98] In all, the Alsos Mission captured 436 tonnes (481 short tons) of black oxide in the form of various compounds in Europe.[5]

Thorium

[edit]Thorium was added to the Combined Development Trust's bailiwick because Glenn T. Seaborg had discovered that under neutron bombardment, thorium could be transmuted into uranium-233, a fissile isotope of uranium.[99][100] Thorium therefore offered an alternative to uranium which was (incorrectly) believed to be scarce. While control of the Congolese, Canadian and American sources gave the Combined Development Trust control of 90 per cent of the world's known uranium reserves, a similar dominance over the world's thorium supply was impractical. Nonetheless, the Combined Development Trust set out to secure a large portion of it.[101]

| Country | Primary site | Mining company | Ore content (% U3O8) | U3O8 (tons) | U contained (tons) | Cost (1947 dollars) | Cost ($/kgU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shinkolobwe, Haut-Katanga | Union Minière du Haut-Katanga | 65% | 6,983 | 5,922 | 19,381,600 | 3.27 | |

| Eldorado Mine, Port Radium, Northwest Territories | Eldorado Gold Mines | 1% | 1,137 | 964 | 5,082,300 | 5.27 | |

| Colorado Plateau | Metals Reserve Company, United States Vanadium Corporation, Vanadium Corporation of America, Vitro Manufacturing Company | 0.25% | 1,349 | 1,144 | 2,072,300 | 1.81 | |

| Captured by Alsos Mission | 481 | 408 | |||||

| Market purchase | 270 | 229 | 1,056,130 | 4.61 | |||

| Total | 10,220 | 8,667 | 27,592,330 | 3.18 |

Refining

[edit]Black oxide

[edit]Eldorado's Port Hope refinery was located on the shores of Lake Ontario in buildings originally built in 1847 as part of a grain terminal.[103] When production started in January 1933,[104] there were just 25 employees; this rose to 287 in 1943.[105] To cope with the increased demands of the Manhattan Project, a new building was added, and production was converted from a batch to a continuous process.[103] Its commercial process was designed to process black oxide. Before the war, Port Hope had a capacity of 27 tonnes (30 short tons) per month. This was increased to 140 tonnes (150 short tons) per month.[106]

Ore arrived from Port Radium after having already undergone some gravity and water separation that increased the percentage of uranium oxide to 35–50%. At Port Hope, the concentrate was crushed and a magnet used to remove iron. It was then heated to 593 °C (1,100 °F) to remove sulphides and carbonates by decomposition and arsenic and antimony by volatilisation. It was then re-roasted with salt (NaCl) to form uranium chloride (UCl4). This was treated with sulphuric acid (H2SO4) and sodium carbonate (NaCO3) to form sodium uranyl carbonate (Na4UO2(CO3)3), which was decomposed with sulphuric acid. Caustic soda (NaOH) was then used to create sodium diuranate (soda salt) (Na2U2O7). Boiling removed excess hydrogen sulphide (H2S), and ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH) was added to form ammonium diuranate ((NH4)2U2O7), which was burned in crucible to produce black oxide. This crushed and bagged for shipment.[107][105]

Purity was a major problem. The Manhattan District disliked impurities, particularly rare earth elements like gadolinium because they could be neutron poisons. But higher purity required repeated ammonium hydroxide baths, which were time consuming and expensive. Rather than aiming for 99% purity, it was better to settle for 97% and let Mallinckrodt deal with the problem in St Louis.[108] By 1 January 1947, Eldorado had produced approximately 1,662 tonnes (1,832 short tons) of black oxide from African ore at a cost of $2,528,560 (equivalent to $35,607,099 in 2024), the average processing cost was therefore approximately $0.69 per pound (equivalent to $10 in 2024). In addition to the African ores, Port Hope also produced 768 tonnes (847 short tons) of black oxide from Canadian ores.[106]

All Canadian ores were processed by Eldorado, but African ore concentrates were also processed at three other sites.[109] The Vitro Manufacturing Company processed high-grade African ore at its plant in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, which had originally been built before the war by the Standard Chemical Company to process carnotite ores. It produced soda salt at a cost of approximately $0.78 per pound (equivalent to $10 in 2024). The Manhattan District contracted the Linde Air Products Company to build and operate a plant for refining and processing African and American ores. The contract negotiated was a cost-plus-a-fixed-fee one, with the fee applying only to the operation phase. The total construction cost was $3,040,230 (equivalent to $42,812,419 in 2024), of which $1,759,940 (equivalent to $24,783,417 in 2024) was for the refining phase.[110]

The plant at Tonawanda, New York, was completed in July 1943, and was operating at 110% of its designed capacity of 47 tonnes (52 short tons) of black oxide per month by December. At that point, the plant was switched over to processing low-grade African ore. In November 1944, at the request of the Madison Square Area, processes were modified to increase the efficiency of the extraction of ore from 93% to 95%, but this increased the cost from 80 to 85 cents per pound. Operations switched back to American ore concentrates in December 1944, but these were exhausted by February 1946, and the plant resumed processing of African ore once more. Total production up to 1 July 1946 was 2,203 tonnes (2,428 short tons) of black oxide, at a total operating cost of approximately $5,074,260 (equivalent to $71,455,563 in 2024).[110]

In May 1946, Mallinckrodt commenced construction of a new processing plant in St Louis, which was completed in May 1946.[110]

Brown and orange oxide

[edit]The next step in the refining process was the conversion of black oxide into orange oxide (UO3) and then into brown oxide (UO2).[111] On 17 April 1942,[112] Arthur Compton, the head of the Manhattan Project's Metallurgical Project,[113] along with Frank Spedding and Norman Hilberry,[114] met with Edward Mallinckrodt Sr., the chairman of the board of Mallinckrodt,[115] and inquired whether his company could produce the extremely pure uranium compounds that the Manhattan Project required. It was known that uranyl nitrate (UO2(NO3)2), was soluble in ether ((CH3CH2)2O), and this could be used to remove impurities.[114] This process had never been attempted on a commercial scale, but it had been demonstrated in the laboratory by Eugène-Melchior Péligot a century before. What had also been amply demonstrated in the laboratory was that ether was erratic, explosive and dangerous to work with.[116][117] Mallinckrodt agreed to undertake the work for $15,000 (equivalent to $288,666 in 2024).[114][118] A pilot plant was set up in the alley between Mallinckrodt buildings 25 and K in downtown St. Louis. The pilot plant produced its first uranyl nitrate on 16 May, and samples were sent to the University of Chicago, Princeton University and the National Bureau of Standards for testing.[119][118]

The production process involved adding black oxide to 3,800-litre (1,000 US gal) stainless steel tanks of hot concentrated nitric acid to produce a solution of uranyl nitrate. This was filtered through a stainless steel filter press and then concentrated in 1,100-litre (300 US gal) pots heated by steam coils to 120 °C (248 °F), the boiling point of uranyl nitrate. The molten uranyl nitrate was cooled to 80 °C (176 °F) and then pumped into cold ether that had been chilled to 0 °C (32 °F) through being cycled through an ice water heat exchanger. The purified material was washed with distilled water and then boiled to remove the ether, producing orange oxide.[118][119] This was then reduced to brown oxide by heating in a hydrogen atmosphere.[111] The production plant was established in two empty buildings: the dissolving and filtering was conducted in Building 51 and the ether extraction and aqueous re-extraction in Building 52. The plant operated around the clock,[118][119] and by July it was producing a ton of brown oxide each day, six days a week, a a unit price of $3.44 per kilogram ($1.56/lb) (equivalent to $65/kg in 2024).[111]

Compton later recalled that Nichols dropped by his office and told him: "we have finally signed the contract with Mallinckrodt for processing the first sixty tons of uranium. It was the most unusual situation that I have ever met. The last of the material was shipped from their plant the day before the terms were agreed upon and the contract signed."[120] The purified uranium oxide was used in experimental sub-critical nuclear reactors built under the direction of Enrico Fermi, which demonstrated the feasibility of a reactor fueled with uranium oxide and moderated with graphite.[121] As various improvements were incorporated into the process, the plant's capacity rose from its designed capacity of 47 tonnes (52 short tons) per month to 150 tonnes (165 short tons) per month. At the same time, the cost of brown oxide fell from $2.45 to $1.54 per kilogram ($1.11 to $0.70/lb) (equivalent to $46/kg to $29/kg in 2024), so Mallinckrodt refunded $332,000 (equivalent to $6,389,141 in 2024) to the government.[111]

The Mallinckrodt plant closed in May 1946, by which time it had produced 3,800 tonnes (4,190 short tons) of brown and orange oxide at a cost of $4,745,250 (equivalent to $91,319,485 in 2024). In May 1945, Mallinckrodt decided to build a new brown oxide plant. Construction commenced on 15 June 1945, and was completed on 15 June 1946. Between then and 1 January 1947, it produced 460 tonnes (507 short tons) of brown and orange oxide at a unit cost of $1.81 per kilogram ($0.82/lb) (equivalent to $35/kg in 2024).[111]

Additional brown oxide plants were operated by Linde in Tonawanda, and DuPont in Deepwater, New Jersey, using the process devised by Mallinckrodt, but only Mallinckrodt also shipped orange oxide.[111] Production commenced at Deepwater in June 1943, and by 1 January 1947 it had produced 1,790 tonnes (1,970 short tons) of brown oxide. Much of the feed was recovered scrap material. Production commenced at Tonawanda in August 1943 and it produced 270 tonnes (300 short tons) of brown oxide before being closed in the Spring of 1944. Mallinckrodt was already producing 100 tonnes (110 short tons) of brown oxide per month or the Manhattan Project's requirement for 150 tonnes (160 short tons) and Union Carbide wanted to use the facilities for nickel compounds production for the K-25 project.[122]

Green salt and hexafluoride

[edit]Uranium metal

[edit]

| Refined uranium compound production until 1 January 1947 (tons)[123] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contractor | Total | ||||||

| Vitro | 768 | 768 | |||||

| Eldorado | 2,679 | 2,679 | |||||

| Linde | 2,428 | 300 | 2,060 | 4,788 | |||

| Mallinckrodt | 4,697 | 2,926 | 1,364 | 8,987 | |||

| DuPont | 982 | 1,970 | 716 | 232 | 3,900 | ||

| Harshaw | 1,640 | 1,615 | 3,255 | ||||

| Electro-Met | 1,538 | 1,538 | |||||

| Iowa State | 972 | 972 | |||||

| Metal Hydrides | 41 | 41 | |||||

| Westinghouse | 69 | 69 | |||||

| Total | 768 | 6,089 | 6,967 | 7,342 | 1,615 | 4,216 | 26,997 |

Geological exploration

[edit]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Dahlkamp 1993, pp. 5–7.

- ^ a b Manhattan District 1947a, pp. S4–S5.

- ^ a b Nichols 1987, p. 47.

- ^ Swain, Frank (4 August 2020). "The forgotten mine that built the atomic bomb". BBC. Retrieved 19 February 2025.

- ^ a b Manhattan District 1947a, pp. 5.1–5.2.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Jones 1985, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, pp. 322–325.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 39–42.

- ^ a b Jones 1985, pp. 41–44.

- ^ Jones 1985, pp. 74–77.

- ^ a b Groves 1962, p. 33.

- ^ Nichols 1987, p. 45.

- ^ Reed 2014, pp. 463–464.

- ^ a b c Manhattan District 1947a, pp. 1.15–1.16.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 307.

- ^ "Thomas T. Crenshaw Jr. '31". Princeton Alumni Weekly. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

- ^ a b c d Jones 1985, p. 308.

- ^ Harris 1962, p. 30.

- ^ Nichols 1987, p. 101.

- ^ Manhattan District 1947a, pp. S1–S4.

- ^ a b Clark 1961, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Bothwell 1984, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Helmreich 1986, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Groves 1962, p. 34.

- ^ Clark 1961, p. 190.

- ^ a b c Norris 2002, p. 326.

- ^ Reed 2014, pp. 467–468.

- ^ "From Rumor to Reality: Staten Island's Radioactive History". Waterfront Alliance. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ Groves 1962, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Helmreich 1986, p. 8.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 79.

- ^ Nichols 1987, pp. 43–46.

- ^ Groves 1962, p. 37.

- ^ Helmreich 1986, p. 9.

- ^ a b Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 291.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 80.

- ^ Manhattan District 1947a, pp. 2.5–2.6.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 168–173.

- ^ Bernstein 1976, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 296.

- ^ Helmreich 1986, p. 16.

- ^ Gowing 1964, p. 301.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 299.

- ^ Jones 1985, pp. 90, 299–306.

- ^ a b Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 285–286.

- ^ Helmreich 1986, p. 18.

- ^ Helmreich 1986, p. 35.

- ^ Helmreich 1986, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b c d Gowing & Arnold 1974, pp. 102–103.

- ^ a b Gowing & Arnold 1974, pp. 358–359.

- ^ a b Helmreich 1986, p. 117.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974, p. 356.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 655.

- ^ a b Manhattan District 1947a, pp. 2.6–2.7.

- ^ a b c d Jones 1985, pp. 310–311.

- ^ a b Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Bothwell 1984, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Bothwell 1984, pp. 23–25.

- ^ "Science: Radium". Time. Retrieved 25 February 2025.

- ^ Bothwell 1984, pp. 55–57.

- ^ "How Canada supplied uranium for the Manhattan Project". CBC Documentaries. Retrieved 25 February 2025.

- ^ "Science: Radium". Time. Retrieved 25 February 2025.

- ^ Bothwell 1984, pp. 11–15.

- ^ a b Keith, Ronald A. (15 November 1945). "Port Radium's Eldorado - The Mine that Shook the World". Maclean's Magazine. Retrieved 26 February 2025 – via Republic of Mining.

- ^ Bothwell 1984, pp. 66–67.

- ^ "Discouraging Difficulties Overcome by Eldorado Pioneers". Edmonton Bulletin. 11 December 1945. p. 16. Retrieved 26 February 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Bothwell 1984, pp. 11, 41.

- ^ a b c d Manhattan District 1947a, p. 3.1.

- ^ Bothwell 1984, pp. 71–75.

- ^ a b c d Bothwell 1984, pp. 102–107.

- ^ Bothwell 1984, pp. 119–121.

- ^ a b Bothwell 1984, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Bothwell 1984, p. 149.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 29.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 65.

- ^ Bothwell 1984, p. 110.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 182–187.

- ^ Villa 1981, pp. 142–145.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 85.

- ^ a b c Manhattan District 1947a, pp. 4.1–4.3.

- ^ "Manhattan Project: Places > Other Places > Uranium Milling and Processing Facilities". OSTI. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ Manhattan District 1947a, pp. 5.1–5.3.

- ^ Groves 1962, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Groves 1962, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Pash 1969, pp. 82–86.

- ^ a b Groves 1962, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 287.

- ^ Pash 1969, p. 98.

- ^ Pash 1969, pp. 111–116.

- ^ Pash 1969, pp. 119–124.

- ^ Jones 1985, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Goudsmit 1947, pp. 188–190.

- ^ Mahoney 1981, p. 311.

- ^ Pash 1969, p. 198.

- ^ Groves 1962, p. 237.

- ^ Pash 1969, pp. 207–210.

- ^ Beck et al. 1985, pp. 556–559.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 286-287.

- ^ Seaborg, G. T.; Gofman, J. W.; Stoughton, R. W. (15 March 1947). "Nuclear Properties of U233: A New Fissionable Isotope of Uranium". Physical review. 71: 378. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.71.378.2. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ Helmreich 1986, pp. 46–51.

- ^ Reed 2014, p. 467.

- ^ a b Arsenault 2008, p. 45.

- ^ Pochon 1937, p. 362.

- ^ a b Arsenault 2008, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b Manhattan District 1947a, pp. 7.1–7.3.

- ^ Pochon 1937, pp. 363–364.

- ^ Bothwell 1984, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Manhattan District 1947a, p. S9.

- ^ a b c Manhattan District 1947a, pp. 7.4–7.7.

- ^ a b c d e f Manhattan District 1947a, pp. 8.1–8.4.

- ^ Fleishman-Hillard 1967, p. 18.

- ^ Compton 1956, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b c Ruhoff & Fain 1962, p. 4.

- ^ "Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr. 1878–1967". Radiology. 88 (3): 594. 1 March 1967. doi:10.1148/88.3.594.

- ^ Fleishman-Hillard 1967, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Compton 1956, p. 93.

- ^ a b c d Fleishman-Hillard 1967, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Ruhoff & Fain 1962, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Compton 1956, p. 95.

- ^ Smyth 1945, p. 96.

- ^ Manhattan District 1947a, pp. 8.4–8.7.

- ^ Reed 2014, pp. 472–473.

References

[edit]- Arsenault, J.E. (March 2008). "Eldorado Port Hope Refinery – Uranium Production (1933–1951)" (PDF). Canadian Nuclear Society Bulletin. 25 (1): 44–47. ISSN 0714-7074. Retrieved 28 February 2025.

- Bernstein, Barton J. (June 1976). "The Uneasy Alliance: Roosevelt, Churchill, and the Atomic Bomb, 1940–1945". The Western Political Quarterly. 29 (2). University of Utah: 202–230. doi:10.2307/448105. JSTOR 448105.

- Bothwell, Robert (1984). Eldorado: Canada's National Uranium Company. University of Toronto Press. doi:10.3138/9781442674332.

- Beck, Alfred M.; Bortz, Abe; Lynch, Charles; Mayo, Lida; Weld, Ralph F. (1985). The Corps of Engineers: The War Against Germany (PDF). United States Army in World War II: The Technical Services. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 455982008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- Clark, Ronald W. (1961). The Birth of the Bomb: Britain's Part in the Weapon that Changed the World. London: Phoenix House. OCLC 824335.

- Compton, Arthur (1956). Atomic Quest. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 173307.

- Dahlkamp, Franz J. (1993). Uranium Ore Deposits. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-53264-4. OCLC 23213888.

- Fleishman-Hillard (1 January 1967). Fuel for the Atomic Age: Completion Report on St. Louis-Area Uranium Processing Operations, 1942–1967 (Report). St. Louis, Missouri. doi:10.2172/4137766. OSTI 4137766.

- Goudsmit, Samuel A. (1947). Alsos. New York: Henry Schuman. ISBN 0-938228-09-9. OCLC 8805725.

- Gowing, Margaret (1964). Britain and Atomic Energy, 1935–1945. London: Macmillan Publishing. OCLC 3195209.

- Gowing, Margaret; Arnold, Lorna (1974). Independence and Deterrence: Britain and Atomic Energy, 1945–1952. Vol. 1, Policy Making. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-15781-8. OCLC 611555258.

- Groves, Leslie (1962). Now it Can be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-306-70738-1. OCLC 537684.

- Harris, John (June 1962). "The Magic Key: E = mc2" (PDF). Mallinckrodt Uranium Division News. 7 (3 and 4): 25–31. Retrieved 18 February 2025.

- Helmreich, Jonathon E. (1986). Gathering Rare Ores: The Diplomacy of Uranium Acquisition, 1943–1954. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04738-3. OCLC 13269027.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, 1939–1946 (PDF). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07186-7. OCLC 637004643. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Hoddeson, Lillian; Henriksen, Paul W.; Meade, Roger A.; Westfall, Catherine L. (1993). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943–1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44132-2. OCLC 26764320.

- Jones, Vincent (1985). Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic Bomb (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 10913875. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- Mahoney, Leo J. (1981). A History of the War Department Scientific Intelligence Mission (ALSOS), 1943–1945 (PhD thesis). Kent State University. OCLC 223804966.

- Manhattan District (1947a). Feed Materials and Special Procurement (PDF). Manhattan District History, Book VII: Feed Materials, Special Procurement, and Geographical Exploration [uranium]. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: Manhattan District. Retrieved 16 February 2025.

- Manhattan District (1947b). Geographical Exploration (PDF). Manhattan District History, Book VII: Feed Materials, Special Procurement, and Geographical Exploration [uranium]. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: Manhattan District. Retrieved 16 February 2025.

- Nichols, Kenneth (1987). The Road to Trinity: A Personal Account of How America's Nuclear Policies Were Made. New York: William Morrow and Co. ISBN 0-688-06910-X. OCLC 15223648.

- Norris, Robert S. (2002). Racing for the Bomb: General Leslie R. Groves, the Manhattan Project's Indispensable Man. South Royalton, Vermont: Steerforth Press. ISBN 1-58642-039-9. OCLC 48544060.

- Pash, Boris (1969). The Alsos Mission. New York: Charter Books. OCLC 568716894.

- Pochon, Marchel (1 July 1937). "Radium Recovery: Canada's Unique Chemical Industry". Chemical & Metallurgical Engineering. 44 (7). ISSN 0095-8476. Retrieved 1 March 2025 – via Internet Archive.

- Reed, B. Cameron (2014). "The Feed Materials Program of the Manhattan Project: A Foundational Component of the Nuclear Weapons Complex". Physics in Perspective. 16 (4): 461–479. doi:10.1007/s00016-014-0146-4. ISSN 1422-6944.

- Rhodes, Richard (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-44133-7. OCLC 13793436.

- Ruhoff, John; Fain, Pat (June 1962). "The First Fifty Critical days" (PDF). Mallinckrodt Uranium Division News. 7 (3 and 4): 3–9. Retrieved 18 February 2025.

- Smyth, Henry DeWolf (1945). Atomic Energy for Military Purposes: the Official Report on the Development of the Atomic Bomb under the Auspices of the United States Government, 1940–1945. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. OCLC 770285.

- Villa, Brian L. (1981). "Chapter 11: Alliance Politics and Atomic Collaboration, 1941–1943". In Sidney, Aster (ed.). The Second World War as a National Experience: Canada. The Canadian Committee for the History of the Second World War, Department of National Defence. OCLC 11646807. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

Category:History of the Manhattan Project Category:Uranium mining