Tongu do dia toinges mo thúath

Tongu do dia toinges mo thúath is an Old Irish oath which translates to "I swear by the god by whom my people (túath) swear". It is the standard oath in early Irish literature. Such formulae are common in early Irish literature, and especially in the heroic sagas, where they are sworn for emphasis when a characters declares they will perform some feat.

Some scholars have interpreted this oath as a relic of Irish Celtic paganism, preserved in Irish literature. Along these lines, Joseph Vendryes argued that the god behind this oath was the Celtic god Teutates, and Calvert Watkins that the oath had roots in proto-Indo-European. On the other hand, Ruairí Ó hUiginn has argued that the oath was a scholarly Christian invention, contrived to suit the pagan background of the Old Irish sagas. The aspect of taboo in this oath has also been discussed, with John T. Koch suggesting that it originated as a taboo deformation.

Tongu do dia in early Irish literature

[edit]Early Irish literature comprises the extensive literary productions of Ireland, in both Irish and Latin, dating between the 5th and 12th centuries CE. The Christianization of Ireland was in process by the 5th century CE, and the earliest written literature from Ireland is Christian in nature. However, the secular narrative literature of early medieval Ireland (and especially the prose sagas) is frequently set in a pagan, heroic past. These sagas were written down by monks and our earliest manuscripts of them are monastic in provenance. The degree to which early Irish literature was influenced by Christianity is vigorously debated, with "revisionists", who stress Christian influence, on one side and "nativists", who stress indigenous and pagan influences, on the other.[1][2][3]

Oath-taking was an important part of medieval Irish society, both Christian and pre-Christian. Oaths were a feature of legal processes, but were also made in everyday life to emphasise assertions.[4] In early Irish literature, and especially in the heroic sagas, characters are frequently made to swear formulaic oaths, preceding declarations that the character will perform some action or fulfil some threat. The Ulster Cycle contains a number of such scenes.[5][6] For example, in the the earliest recension of the Ulster Cycle saga Táin Bó Cúailnge, when the hero Cú Chulainn is told that to kill Fóill, son of Nechtain Scéne, he must kill him with the first blow, he says the following:

tongu do dia toinges mo thúath, nocon imbéra-som for Ultu a cles sin dorísse diano tárle mánaís mo phoba Conchobair as mo láim-sea

I swear by the god by whom my people swear, he shall not play that trick again on Ulstermen, if once the broad spear of my master Conchobar reach him from my hand.[7]

The oath in this passage, tongu do dia toinges mo thúath ("I swear by the god by whom my people swear"), is the standard oath in early Irish literature.[8] It appears in several forms in Irish literature (Ó hUiginn has listed 25), though the variation is more limited in the Old Irish period, only diversifying in the transition to Middle and Early Modern Irish. Aside from the form in the passage above, the commonest forms in the Old Irish period are tongu dia toinges mo thúath ("I swear by the god by whom my people swear"), tongu a toinges mo thiath immurgu ("I swear indeed by what my people swear") and tongu do dia a tonges mo thiath ("I swear to god what my people swear").[9] In later Irish texts, plural "gods" is commonly substituted for "god" in order to emphasise the pagan aspect of the oath.[10] The word thúath (a lenition of túath) is translated here as "people", but is occasionally also translated as "tribe".[11][12]

Interpretation

[edit]

Some have interpreted the oath as a genuine Celtic pagan formula, preserved in early Irish literature.[10] Joseph Vendryes suggested that the Celtic god Teutates, a tribal deity whose name has the same root as túath, was the pagan god behind this oath.[13] Vendryes has been followed in this proposal by Myles Dillon[14] and Proinsias Mac Cana.[12] Gearóid Mac Niocaill proposed that the function of the pagan god behind this oath was the tribe's ancestor god. Kenneth H. Jackson proposed that the god was the tribe's tutelary god.[10]

Against the identifications of the phrase as a remnant of pagan culture, Ó hUiginn has argued that the phrase "has every appearance of being a contrived learned phrase", an innovation in the early Irish epics dating to the Christian period rather than "an inherited pre-Christian archaism".[5] He argues that the archaic grammatical features in this phrase show a "syntactic imbalance", which would be unexpected in a genuine idiomatic expression. His proposal is that a Christian author attempted to contrive an archaic pagan oath (suitable to the pagan background of the Old Irish epics) out of the Christian formula toing do dia ("I swear to god").[15] Kim McCone and Tom Sjöblom have followed Ó hUiginn's analysis.[16][17]

Calvert Watkins, who points to "conservative nature of the [Irish] language and of oath-taking in general", has paralleled this oath with two others from Indo-European languages: (1) an oath of the Kievan Rus' from the Primary Chronicle, "May we be accursed of the god whom we worship",[a] and (2) an oath from a litany of the mysteries of Isis, "I swear by the gods whom I worship".[b] He suggests that these oaths, with the peculiar feature of invoking one's own gods in a restrictive relative clause, ultimately derive from an proto-Indo-European oath.[18] Watkins does not agree with Ó hUiginn that the phrase shows "syntactic imbalance". He considers Ó hUiginn's proposed explanation of the phrase "most unlikely", in view of the absence of documentation for this development, and the small number attestations of the Christian formula.[19]

The aspect of taboo in the oath (which avoids the name of the god being sworn by) has also been noted.[20][13] Vendryes argued that the suppression of the name of the god in an oath to that god was typical of Celtic religion. He compares it to Strabo's reference to a nameless god of the Celtiberians, and Lucan's poetic description in the Pharsalia of Gauls dreading gods whom they do not know.[13]

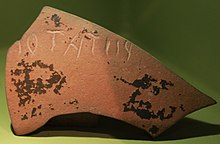

John T. Koch proposed that the formula, alongside the Welsh oath tyghaf tyghet ("I swear a destiny on you") and a Gaulish phrase from the Chamalières tablet,[c] originated as a "taboo deformation" of an oath sworn to Lugus (a god whose name, he argues, derives from a Celtic word for oath).[22] Stefan Schumacher and Thomas Charles-Edwards have argued that identifying the Welsh and Irish oaths poses difficulties, as the pun in the Welsh oath between tyngaf 'to swear' and tynghaf 'to destine' relies on phonological developments unique to Middle Welsh, not traceable to proto-Celtic, where the words are unconnected.[17]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Original Church Slavonic: "da iměemŭ kljatvŭ otŭ boga vů níže věruemů".[18]

- ^ Original Greek: "epómnumai dè kai hoùs proskunō theoús".[18] For more on this oath see Burkert 1987, p. 50.

- ^ The phrase in question is toncnaman toncsiiontio (lines 7-8), which is of uncertain meaning.[21] For discussion, see Schmidt 1981, pp. 266–267, Koch 1992, pp. 249–251, and Lambert 2002, pp. 278–279.

References

[edit]- ^ McCone 1991, pp. 1–7.

- ^ Ó Cathasaigh 2006, pp. 10–11, 24–26.

- ^ Johnston 2003, p. 342.

- ^ Ó Murchú 1992, pp. 330–331.

- ^ a b Ó hUiginn 1989, p. 340.

- ^ Watkins 1990, p. 48.

- ^ Ó hUiginn 1989, p. 332.

- ^ Sjöblom 2000, p. 97.

- ^ Ó hUiginn 1989, pp. 332–337.

- ^ a b c Ó hUiginn 1989, p. 338.

- ^ McCone 1991, p. 234.

- ^ a b Mac Cana 1970, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Vendryes 1948, p. 33.

- ^ Dillon 1964, p. 60.

- ^ Ó hUiginn 1989, pp. 338–339.

- ^ McCone 1991, pp. 234–235.

- ^ a b Sjöblom 2000, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Watkins 1989, p. 792.

- ^ Watkins 1990, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Sjöblom 2000, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Lambert 2002, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Koch 1992, pp. 252, 261.

Bibliography

[edit]- Burkert, Walter (1987). Ancient Mystery Cults. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03387-0.

- Dillon, Miles (1964). "Celtic religion and Celtic society". In Raftery, Joseph (ed.). The Celts. Cork / Dublin: The Mercier Press. pp. 59–71.

- Koch, John Thomas (1992). "Further to tongu do dia toinges mo thúath, &c". Études Celtiques. 29: 249–261. doi:10.3406/ecelt.1992.2008.

- Johnston, Elva (2003). "Early Irish History: The State of the Art". Irish Historical Studies. 33 (131): 342–348. JSTOR 30006933.

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves (2002). "L-100". Recueil des inscriptions gauloises. II, fasc. 2, Textes gallo-latins sur instrumentum. Paris: Éd. du CNRS. pp. 269–280.

- Mac Cana, Proinsias (1970). Celtic Mythology (1st ed.). Feltham: Hamlyn.

- McCone, Kim (1991). Pagan Past and Christian Present in Early Irish Literature. Maynooth Monographs. Vol. 3. Maynooth: An Sagart.

- Ó Cathasaigh, Tomás (2006). "The Literature of Medieval Ireland to c. 800: St Patrick to the Vikings". In Kelleher, Margaret; O’Leary, Philip (eds.). The Cambridge History of Irish Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–31.

- Ó Murchú, Liam P. (1992). "The literary asseveration in Irish". Études Celtiques. 29: 327–332. doi:10.3406/ecelt.1992.2015.

- Ó hUiginn, Ruairí (1989). "Tongu do dia toinges mo thúath and related expressions". In Ó Corráin, D.; Breatnach, L.; McCone, K. (eds.). Sages, Saints and Storytellers: Celtic Studies in Honour of Professor James Carney. Maynooth: An Sagart. pp. 332–341.

- Schmidt, K.-H. (1981). "The Gaulish inscription of Chamalières". Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies. 29: 256–268.

- Sjöblom, Tom (2000). Early Irish Taboos: A Study in Cognitive History. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. ISBN 978-951-45-9071-9.

- Vendryes, Joseph (1997) [1948]. La religion des Celtes. Spézet: Coop Breizh.

- Watkins, Calvert (1989). "New parameters in historical linguistics, philology, and culture history". Language. 65 (4): 783–799. JSTOR 414934.

- Watkins, Calvert (1990). "Some Celtic phrasal echoes". In Matonis, A. T. E.; Melia, D. F. (eds.). Celtic Language, Celtic Culture: A Festschrift for Eric P. Hamp. Van Nuys, CA: Ford & Bailie. pp. 47–56.

Further reading

[edit]- Breatnach, Liam (1980). "Some remarks on the relative in Old Irish". Ériu. 31: 1–9. JSTOR 30008209.

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas (1995). "Mi a dynghaf dynghed and related problems". In Eska, J. F.; Gruffydd, R. G.; Jacobs, N. (eds.). Hispano-Gallo-Brittonica: Essays in Honour of Prof. Ellis Evans. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. pp. 1–15.

- Dictionary of the Irish Language, s.v., "tongaid".

- Murray, Kevin (2003). "A reading from Scéla Moṡauluim". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie. 53 (1): 198–201. doi:10.1515/ZCPH.2003.198.

- Schumacher, Stefan (1995). "Old Irish *tucaid, tocad and Middle Welsh tynghaf tynghet re-examined". Ériu. 46: 49–57. JSTOR 30007873.