The Oceanic Languages

First-edition hardcover | |

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Series | Routledge Language Family Series |

Release number | 4 |

| Subject | Oceanic languages |

| Genre | Reference work |

| Publisher | Curzon Press |

Publication date | 2002 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Pages | 924 |

| ISBN | 978-0-7007-1128-4 (Original hardback) |

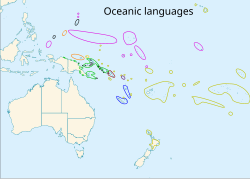

The Oceanic Languages is a 2002 reference work by John Lynch, Malcolm Ross, and Terry Crowley, about the Oceanic family of languages, the largest subgroup of the Austronesian phylum. It is the only formal survey of the field and a standard reference work for scholars of the Oceanic languages. The book's ubiquity among Oceanic linguists has led to its being referred to simply as "the blue book".

The book contains five introductory chapters which describe the history of the languages, their structure, the sociolinguistic considerations, and the relationship the languages have with each other, as well as a look at their reconstructed common ancestor, Proto-Oceanic. These five chapters are then followed by a sample of sketches for forty-three languages. The book was written in part to expand on the previous works of Robert Henry Codrington and Sidney Herbert Ray whose work was then outdated and constrained mostly to Melanesian languages. Although it contains a substantial number of typos and some reviewers criticized some editorial choices, the book was well-received and remains in use as a standard reference for linguists.

Content

[edit]

The Oceanic Languages is a 924-page survey of the field which describes in detail the Oceanic subgroup of the larger Austronesian language family, its largest subfamily.[1][2] The book is the first and, as of 2017, only survey of its kind on the Oceanic languages, intending in part to displace Robert Henry Codrington's 1861 book The Melanesian Languages and Sidney Herbert Ray's 1926 book A Comparative Study of the Melanesian Island Languages, which only covered central and southern Melanesia.[3] Published by Curzon Press in 2002, it was coauthored and co-edited by John Lynch, Malcolm Ross, and Terry Crowley.[1][2] Unlike Lynch's 1998 textbook The Pacific Languages, the book is designed as a documentational resource for experts in the field rather than as an introduction for undergraduate students.[1] The book contains five introductory chapters: an overview of the language family, the sociolinguistic considerations, the linguistic typology, an outline of the most recent common ancestor Proto-Oceanic, and an analysis of the linguistic phylogeny, or how the languages are related to one another.[1]

Following the introductory chapters, the book contains individual sketches for forty-three languages as a sample of the 466 Oceanic languages listed by the authors, which makes up the majority of the book.[1][4] The authors largely provide their own expertise on each of the languages either alone or together with one of the other coauthors, such as Banoni, which was cowritten by Lynch and Crowley; twelve of the analyses, however, are written by other experts and several others are adapted from other sources, including unpublished grammars.[1][5] Only one of the contributing authors was a native speaker of the sketch languages – Rex Horoi, an Arosi speaker – but twenty-four of the sketches are based on original fieldwork by fifteen of the contributing authors, principal among them being Ross.[5] Several of the languages found in the book had never before had their grammars examined in print.[6]

Reception

[edit]The ubiquity of The Oceanic Languages among scholars in the field, and the color of its cover, have led to its being known simply as "the blue book".[7] The linguists Paul Geraghty and Andrew Pawley have described the work as "a standard reference book" for use in the field.[7] The American linguist Robert Blust wrote that the volume is "no ordinary book" and that "in every respect it reflects the tremendous advances in factual knowledge and theory" following Ray's 1926 work.[1] Blust took particular issue with what he saw as editorial laziness, "idiosyncratic" word choices, and the questionable exclusion of some topics. For example, he finds several prominent typos throughout and expresses annoyance at what appears to be Crowley's insistence on using the word "copying" for the more conventional term "borrowing".[8] He remarks that discussion of nominal derivation from locatives – a poorly understood but typologically common derivative process among Austronesian languages – and the historical relationship between the passive and imperative grammatical functions are notable absences from the discussion.[9]

René van den Berg, a linguist at SIL, praised the book in 2004, predicting it "will be the major reference work on the area for many years".[10] Van den Berg called the decision to shy away from jargon a remarkably "wise decision", as it will make the book accessible to a wider audience. His review was not completely laudatory, however; he criticized the book for its sparse analysis of language preservation in the Pacific and the lack of attention paid to Proto-Oceanic vocabulary, for which a significant body of work exists.[11] Van den Berg took a middle approach to the authors' deliberate exclusion of more well-known Oceanic languages from the sketch section of the book, arguing that it was somewhat unreasonable to exclude particular languages which were influential to other Oceanic languages, as Tolai was to Tok Pisin, or culturally important languages to a region, such as Māori.[5]

The German linguist Gunter Senft writes that the book's writers achieve its "ambitious goals" of improving on the work of Codrington and Ray "in an admirable way".[12] He praises the authors' "bonanza" of useful and interesting information and applauds the phylogeny found after the forty-three sketches conclude.[13] Besides echoing Blust's irritation at the numerous typos, he also points out a number of editorial oversights, including not quoting sources in the bibliography section and a logical inconsistency between its typology and Proto-Oceanic sections.[13] Nevertheless, Senft describes the book as "a must not only for Austronesianists, but also for typologists and comparativists" and opines that the book "will be one of the most helpful, central, and basic reference tools" for them.[14]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Blust 2005, p. 544.

- ^ a b Senft 2004, p. 515.

- ^

- For the book being the first of its kind, see Blust 2005, p. 544.

- For its being the only, see Ross 2017, p. d.

- For its replacing Ray (1926), see Geraghty & Pawley 2021, p. 493 and Senft 2004, pp. 515–516.

- For its replacing Codrington (1861), see Senft 2004, pp. 515–516.

- ^ Van den Berg 2004, p. 130.

- ^ a b c Van den Berg 2004, p. 132.

- ^ Senft 2004, p. 518.

- ^ a b Geraghty & Pawley 2021, p. 493.

- ^ Blust 2005, pp. 544, 549.

- ^ Blust 2005, pp. 545–546.

- ^ Van den Berg 2004, p. 133.

- ^ Van den Berg 2004, p. 131.

- ^ Senft 2004, p. 516.

- ^ a b Senft 2004, pp. 518–519.

- ^ Senft 2004, p. 519.

Sources

[edit]- Blust, R. A. (2005). "The Oceanic languages (review)". Oceanic Linguistics. 44 (2): 544–558. doi:10.1353/ol.2005.0030. ISSN 1527-9421.

- Geraghty, Paul; Pawley, Andrew (2021). "John Dominic Lynch (1946–2021)". Oceanic Linguistics. 60 (2): 489–502. doi:10.1353/ol.2021.0016. ISSN 1527-9421.

- Ross, Malcolm (27 September 2017). Oceanic Languages (Report). doi:10.1093/obo/9780199772810-0172. Retrieved 12 May 2025.

- Senft, Gunter [in German] (25 January 2004). "[Review of the book The Oceanic Languages by John Lynch, Malcolm Ross and Terry Crowley]" (PDF). Linguistics. 42 (2): 515–520. doi:10.1515/ling.2004.016. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-1BFD-2. ISSN 0024-3949.

- Van den Berg, René (2004). "John Lynch, Malcolm Ross and Terry Crowley (eds), The Oceanic languages. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 2002, xvii + 924 pp. ISBN 0.7007.1128.7. Price: GBP 165 (hardback)". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 160 (1). Brill: 130–133. ISSN 0006-2294. JSTOR 27868107.