The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra

The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra is a book written and illustrated by H. S. M. Coxeter, P. Du Val, H. T. Flather and J. F. Petrie. It enumerates certain stellations of the regular convex or Platonic icosahedron, according to a set of rules put forward by J. C. P. Miller.

First published by the University of Toronto in 1938, a Second Edition reprint by Springer-Verlag followed in 1982. Tarquin's 1999 Third Edition included new reference material and photographs by K. and D. Crennell.

Stellating polyhedra

[edit]

|

|

|

A polyhedron is stellated by extending the face planes of a polyhedron until they meet again to form a new polyhedron or compound. The interior of the new polyhedron is divided by the face planes into a number of cells. When extended indefinitely, the face planes of a polyhedron may divide space into a great many such cells. Different cell sets then yield different stellations.

For a symmetrical polyhedron, these cells will fall into groups, or sets, of congruent cells – we say that the cells in such a congruent set are of the same type. This can still lead to a large number of possible forms, so further criteria are often imposed to reduce the set to those stellations that are significant and unique in some way.

A set of cells forming a closed layer around its core is called a shell. A shell may be made up of one or more cell types.

Among the Platonic solids, the tetrahedron and cube have no stellations, the octahedron has one (stella octangula), the dodecahedron has three (stellated dodecahedron, great dodecahedron and great stellated dodecahedron) and the icosahedron has a much larger number.

Antecedents

[edit]The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra is not the first work about stellated icosahedra.

In 1809 Louis Poinsot discovered the first recognised examples, the great icosahedron (G in the list below) and the great dodecahedron, completing the set of what are nowadays known as the regular star or Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra.[1]

In 1876 Edmund Hess used stellation diagrams and discovered the remaining mainline stellated icosahedra. (B to F and H in the list below) [2][3]

In 1900 Max Brückner described and photographed many stellated icosahedra in his book Vielecke und Vielflache: Theorie und Geschichte (Polygons and polyhedra: Theory and History, Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, 1900).[4]

In 1924 A. Harry Wheeler gave a talk as an Invited Speaker of the ICM in 1924 at Toronto.[5] In his talk he presented the method of selecting regions of the stellation diagram and combining their cells to form new polyhedral figures. Wheeler included hollow polyhedra and sets of discrete (non connected) cells. Wheeler was initially to be a co-author of The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra, but he objected to Coxeter's approach, which he found so “involved and clumsy that I did not want to have anything to do with it. ... Coxeter has a way of taking a subject and tying it up into knots in such a way that I find it quite difficult to follow him and some times to even make sense.”[6]

Authors' contributions

[edit]Miller's rules

[edit]Although Miller did not contribute to the book directly, he was a close colleague of Coxeter and Petrie. His contribution is immortalised in his set of rules for defining which stellation forms should be considered "properly significant and distinct":

(i) The faces must lie in twenty planes, viz., the bounding planes of the regular icosahedron.

(ii) All parts composing the faces must be the same in each plane, although they may be quite disconnected.

(iii) The parts included in any one plane must have trigonal symmetry, without or with reflection. This secures icosahedral symmetry for the whole solid.

(iv) The parts included in any plane must all be "accessible" in the completed solid (i.e. they must be on the "outside". In certain cases we should require models of enormous size in order to see all the outside. With a model of ordinary size, some parts of the "outside" could only be explored by a crawling insect).

(v) We exclude from consideration cases where the parts can be divided into two sets, each giving a solid with as much symmetry as the whole figure. But we allow the combination of an enantiomorphous pair having no common part (which actually occurs in just one case).[7]

Rules (i) to (iii) are symmetry requirements for the face planes. Rule (iv) excludes buried holes, to ensure that no two stellations look outwardly identical. Rule (v) prevents any disconnected compound of simpler stellations.

Coxeter

[edit]Coxeter was the main driving force behind the work. He carried out the original analysis based on Miller's rules, adopting a number of techniques such as combinatorics and abstract graph theory whose use in a geometrical context was then novel.

He observed that the stellation diagram comprised many line segments. He then developed procedures for manipulating combinations of the adjacent plane regions, to formally enumerate the combinations allowed under Miller's rules.

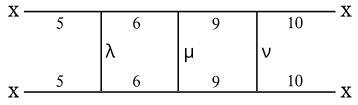

His graph, reproduced here, shows the connectivity of the various faces identified in the stellation diagram (see below). The Greek symbols represent sets of possible alternatives:

- λ may be 3 or 4

- μ may be 7 or 8

- ν may be 11 or 12

Du Val

[edit]Du Val devised a symbolic notation for identifying sets of congruent cells, based on the observation that they lie in "shells" around the original icosahedron. Based on this he tested all possible combinations against Miller's rules, confirming the result of Coxeter's more analytical approach.

Flather

[edit]Flather's contribution was indirect: he made card models of all 59. When he first met Coxeter he had already made many stellations, including some "non-Miller" examples. He went on to complete the series of fifty-nine, which are preserved in the mathematics library of Cambridge University, England. The library also holds some non-Miller models, but it is not known whether these were made by Flather or by Miller's later students.[8]

Petrie

[edit]John Flinders Petrie was a lifelong friend of Coxeter and had a remarkable ability to visualise four-dimensional geometry. He and Coxeter had worked together on many mathematical problems. His direct contribution to the fifty-nine icosahedra was the exquisite set of three-dimensional drawings which provide much of the fascination of the published work.

The Crennells

[edit]For the Third Edition, Kate and David Crennell reset the text and redrew the diagrams. They also added a reference section containing tables, diagrams, and photographs of some of the Cambridge models (which at that time were all thought to be Flather's). Corrections to this edition have been published online.[9]

List of the fifty-nine icosahedra

[edit]

Before Coxeter, only Brückner and Wheeler had recorded any significant sets of stellations, although a few such as the great icosahedron had been known for longer. Since publication of The 59, Wenninger published instructions on making models of some; the numbering scheme used in his book has become widely referenced, although he only recorded a few stellations.

Notes on the list

[edit]Index numbers are the Crennells' unless otherwise stated:

Index

- In the index numbering added to the Third Edition by the Crennells, the first 32 forms (indices 1–32) are reflective models, and the last 27 (indices 33–59) are chiral with only the right-handed forms listed. This follows the order in which the stellations are depicted in the book.

Cells

- In Du Val's notation, each shell is identified in bold type, working outwards, as a, b, c, ..., h with a being the original icosahedron. Some shells subdivide into two types of cell, for example e comprises e1 and e2. The set f1 further subdivides into right- and left-handed forms, respectively f1 (plain type) and f1 (italic). Where a stellation has all cells present within an outer shell, the outer shell is capitalised and the inner omitted, for example a + b + c + e1 is written as Ce1.

Faces

- All of the stellations can be specified by a stellation diagram. In the diagram shown here, the numbered colors indicate the regions of the stellation diagram which must occur together as a set, if full icosahedral symmetry is to be maintained. The diagram has 13 such sets. Some of these subdivide into chiral pairs (not shown), allowing stellations with rotational but not reflexive symmetry. In the table, faces which are seen from underneath are indicated by an apostrophe, for example 3'.

Wenninger

- The index numbers and the numbered names were allocated arbitrarily by Wenninger's publisher according to their occurrence in his book Polyhedron models and bear no relation to any mathematical sequence. Only a few of his models were of icosahedra. His names are given in shortened form, with "... of the icosahedron" left off.

Wheeler

- Wheeler was planned to be one of the coauthors. However, in 1938 Wheeler objected to Coxeter's expository style which he found “involved and clumsy that I did not want to have anything to do with it. ... Coxeter has a way of taking a subject and tying it up into knots in such a way that I find it quite difficult to follow him and some times to even make sense”.[5]

- The numbers and names of Wheeler's icosahedra (which by no means were to be a compete enumeration) are from the talk he gave as an Invited Speaker of the ICM in 1924 at Toronto.[5]

Brückner

- Max Brückner made and photographed models of many polyhedra, only a few of which were icosahedra. Taf. is an abbreviation of Tafel, German for plate.

Remarks

- No. 8 is sometimes called the echidnahedron after an imagined similarity to the spiny anteater or echidna. This usage is independent of Kepler's description of his regular star polyhedra as his echidnae.

Table of the fifty-nine icosahedra

[edit]Some images illustrate the mirror-image icosahedron with the f1 rather than the f1 cell.

| Index | Cells | Faces | Wenninger | Wheeler | Brückner | Remarks | Face diagram | 3D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | 0 | 4 Icosahedron |

1 Regular convex triangular |

Regular icosahedron, a Platonic solid |

|

| |

| 2 | B | 1 | 26 Triakis icosahedron |

2 Hexagonal |

Taf. VIII, Fig. 2 |

First stellation of the icosahedron, small triambic icosahedron, or triakisicosahedron |

|

|

| 3 | C | 2 | 23 Compound of five octahedra |

3 Five intersecting octahedra |

Taf. IX, Fig. 6 |

Regular compound of five octahedra |

|

|

| 4 | D | 3 4 | 4 Nonagonal |

Taf. IX, Fig. 17 |

|

| ||

| 5 | E | 5 6 7 |

|

| ||||

| 6 | F | 8 9 10 | 27 Second stellation |

19 triple 13+6+7 |

Second stellation of icosahedron |

|

| |

| 7 | G | 11 12 | 41 Great icosahedron |

11 Regular star Poinsot |

Taf. XI, Fig. 24 |

Great icosahedron |

|

|

| 8 | H | 13 | 42 Final stellation |

12 Complete |

Taf. XI, Fig. 14 |

Final stellation of the icosahedron or echidnahedron |

|

|

| 9 | e1 | 3' 5 | 37 Twelfth stellation |

Twelfth stellation of icosahedron |

|

| ||

| 10 | f1 | 5' 6' 9 10 |

|

| ||||

| 11 | g1 | 10' 12 | 29 Fourth stellation |

21 Discrete skeleton |

Fourth stellation of icosahedron |

|

| |

| 12 | e1f1 | 3' 6' 9 10 |  |

| ||||

| 13 | e1f1g1 | 3' 6' 9 12 | 20 Hollow, labyrinth |

|

| |||

| 14 | f1g1 | 5' 6' 9 12 |  |

| ||||

| 15 | e2 | 4' 6 7 |  |

| ||||

| 16 | f2 | 7' 8 | 22 Discrete twelve-pointed, crown-rimmed group |

|

| |||

| 17 | g2 | 8' 9'11 |  |

| ||||

| 18 | e2f2 | 4' 6 8 |  |

| ||||

| 19 | e2f2g2 | 4' 6 9' 11 |  |

| ||||

| 20 | f2g2 | 7' 9' 11 | 30 Fifth stellation |

Fifth stellation of icosahedron |

|

| ||

| 21 | De1 | 4 5 | 32 Seventh stellation |

10 Twenty-pointed, six-edged |

Seventh stellation of icosahedron |

|

| |

| 22 | Ef1 | 7 9 10 | 25 Compound of ten tetrahedra |

8 Ten intersecting tetrahedra |

Taf. IX, Fig. 3 |

Regular compound of ten tetrahedra |

|

|

| 23 | Fg1 | 8 9 12 | 31 Sixth stellation |

17 Double 13+ 9 |

Taf. X, Fig. 3 |

Sixth stellation of icosahedron |

|

|

| 24 | De1f1 | 4 6' 9 10 |  |

| ||||

| 25 | De1f1g1 | 4 6' 9 12 |  |

| ||||

| 26 | Ef1g1 | 7 9 12 | 28 Third stellation |

9 Mobius (concave) |

Taf. VIII, Fig. 26 |

Excavated dodecahedron |

|

|

| 27 | De2 | 3 6 7 | 5 Archimedian variety of no 13 |

|

| |||

| 28 | Ef2 | 5 6 8 | 18 Double 13 + 10 |

Taf.IX, Fig. 20 |

|

| ||

| 29 | Fg2 | 10 11 | 33 Eighth stellation |

14 Archimedian variety 11 |

Eighth stellation of icosahedron |

|

| |

| 30 | De2f2 | 3 6 8 | 34 Ninth stellation |

13 Kite archimedian variety no 11 |

Medial triambic icosahedron or Great triambic icosahedron |

|

| |

| 31 | De2f2g2 | 3 6 9' 11 |  |

| ||||

| 32 | Ef2g2 | 5 6 9' 11 |  |

| ||||

| 33 | f1 | 5' 6' 9 10 | 35 Tenth stellation |

Tenth stellation of icosahedron |

|

| ||

| 34 | e1f1 | 3' 5 6' 9 10 | 36 Eleventh stellation |

Eleventh stellation of icosahedron |

|

| ||

| 35 | De1f1 | 4 5 6' 9 10 |  |

| ||||

| 36 | f1g1 | 5' 6' 9 10' 12 |  |

| ||||

| 37 | e1f1g1 | 3' 5 6' 9 10' 12 | 39 Fourteenth stellation |

Fourteenth stellation of icosahedron |

|

| ||

| 38 | De1f1g1 | 4 5 6' 9 10' 12 |  |

| ||||

| 39 | f1g2 | 5' 6' 8' 9' 10 11 |  |

| ||||

| 40 | e1f1g2 | 3' 5 6' 8' 9' 10 11 |  |

| ||||

| 41 | De1f1g2 | 4 5 6' 8' 9' 10 11 |  |

| ||||

| 42 | f1f2g2 | 5' 6' 7' 9' 10 11 |  |

| ||||

| 43 | e1f1f2g2 | 3' 5 6' 7' 9' 10 11 |  |

| ||||

| 44 | De1f1f2g2 | 4 5 6' 7' 9' 10 11 |  |

| ||||

| 45 | e2f1 | 4' 5' 6 7 9 10 | 40 Fifteenth stellation |

Fifteenth stellation of icosahedron |

|

| ||

| 46 | De2f1 | 3 5' 6 7 9 10 |  |

| ||||

| 47 | Ef1 | 5 6 7 9 10 | 24 Compound of five tetrahedra |

7: right handed 6: left handed Five intersecting Tetrahedra |

Taf. IX, Fig. 11 |

Regular Compound of five tetrahedra (right handed) |

|

|

| 48 | e2f1g1 | 4' 5' 6 7 9 10' 12 |  |

| ||||

| 49 | De2f1g1 | 3 5' 6 7 9 10' 12 |  |

| ||||

| 50 | Ef1g1 | 5 6 7 9 10' 12 |  |

| ||||

| 51 | e2f1f2 | 4' 5' 6 8 9 10 | 38 Thirteenth stellation |

Thirteenth stellation of icosahedron |

|

| ||

| 52 | De2f1f2 | 3 5' 6 8 9 10 |  |

| ||||

| 53 | Ef1f2 | 5 6 8 9 10 | 15: right handed 16: left handed Double 13+7 |

|

| |||

| 54 | e2f1f2g1 | 4' 5' 6 8 9 10' 12 |  |

| ||||

| 55 | De2f1f2g1 | 3 5' 6 8 9 10' 12 |  |

| ||||

| 56 | Ef1f2g1 | 5 6 8 9 10' 12 |  |

| ||||

| 57 | e2f1f2g2 | 4' 5' 6 9' 10 11 |  |

| ||||

| 58 | De2f1f2g2 | 3 5' 6 9' 10 11 |  |

| ||||

| 59 | Ef1f2g2 | 5 6 9' 10 11 |  |

|

Subsequent debate

[edit]There has subsequently been some debate on Miller's rules, with some writers questioning them. Flather himself made and exhibited models which were "non-Miller".[10] Bridge (1974) obtained stellations of the icosahedron by dualising facettings of the dodecahedron, noting the significance of internal structure in distinguishing between stellations which Miller's rules treat as identical.[11] Hudson and Kingston (1988) adopted a reduced rule set.[12] Inchbald noted two non-Miller stellations, and went on to discuss various related issues.[13][14]

See also

[edit]- List of Wenninger polyhedron models – Wenninger's book Polyhedron models included 21 of these stellations.

- Solids with icosahedral symmetry

Notes

[edit]- ^ Cromwell (1997)

- ^ Über die zugleich gleicheckigen und gleichflächigen Polyeder. In: Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft zur Beförderung der gesamten Naturwissenschaften zu Marburg (1876).

- ^ Hess, Edmund (1883). Einleitung in die Lehre von der Kugelteilung mit besonderer Berücksichtigung ihrer Anwendung auf die Theorie der Gleichflächigen und der gleicheckigen Polyeder (in German). Teubner.

- ^ Brückner (1900)

- ^ a b c Wheeler (1924)

- ^ Roberts, David L. (1996). "(1873–1950): A Case Study in the Stratification of American Mathematical Activity" (PDF). Historia Mathematica. 23: 269–287. doi:10.1006/hmat.1996.0028.

- ^ Coxeter, du Val, et al (Third Edition 1999) Pages 15-16.

- ^ Inchbald, G.; Some lost stellations of the icosahedron, steelpillow.com, 11 July 2006. [1] (retrieved 14 September 2017)]

- ^ K. and D. Crennell; The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra, Fortran Friends, [2] (retrieved 14 September 2017).

- ^ Tarquin Edition (1999), p.9.

- ^ Bridge, James; "Facetting the Dodecahedron", Acta Crystallographica. Vol A30 (1974). pp.548-552.

- ^ Hudson, J.L. and Kingston, J.G.; "Stellating Polyhedra", Mathematical Intelligencer, Vol 10, No 3, 1988. pp.50-61.

- ^ Inchbald, G. "In Search of the Lost Icosahedra", The Mathematical Gazette, Vol 86, No 506, July 2002. pp.208-215.

- ^ Inchbald, G. "Towards Stellating the Icosahedron and Facetting the Dodecahedron", Symmetry: Culture and Science, Vol 11, Nos 1-4, 2000. pp.269-291.

References

[edit]- Brückner, Max (1900). Vielecke und Vielflache: Theorie und Geschichte [Polygons and Polyhedra: Theory and History]. Leipzig: B.G. Treubner. (in German). OCLC 25080888. (Plate scans at the Internet Archive, at bulatov.org. Reprinted 2004: Michigan Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4181-6590-1.)

- H. S. M. Coxeter, P. Du Val, H. T. Flather, J. F. Petrie (1938) The Fifty-nine Icosahedra, University of Toronto studies, mathematical series 6: 1–26.

- Third edition (1999) Tarquin ISBN 978-1-899618-32-3 MR 0676126

- Cromwell, Peter R. (1997). "Stars, Stellations and Skeletons". Polyhedra . Cambridge University Press. Ch. 7, pp. 249–287. ISBN 0-521-55432-2.

- Wenninger, Magnus J. (1983) Polyhedron models; Cambridge University Press, Paperback edition (2003). ISBN 978-0-521-09859-5.

- Wheeler, Albert Harry (1924) "Certain forms of the icosahedron and a method for deriving and designating higher polyhedra." Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback Machine In Proceedings of the International Mathematical Congress, Toronto, vol. 1, pp. 701–708.

External links

[edit]- Vladimir Bulatov (2001). "An Interactive Creation of Polyhedra Stellations with Various Symmetries" VisMath. Vol. 3, No. 2.

- The fifty nine stellations of the regular icosahedron

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Fifty nine icosahedron stellations". MathWorld.

- Stellations of the icosahedron

- George Hart, 59 Stellations of the Icosahedron - VRML 3D files.

- John L. Hudson (1987). "Set of 70 polyhedron models showing the icosahedron and its 58 stellations". Science Museum, London.

- A. Harry Wheeler. Models at the National Museum of American History. Collection search for "Harry Wheeler icosahedron"