Pinchas Lapide

Pinchas Lapide | |

|---|---|

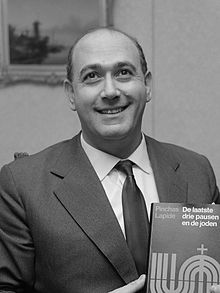

Lapide in 1967 | |

| Born | 28 November 1922 |

| Died | 23 October 1997 (aged 74) |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse | Ruth Lapide |

Pinchas Lapide[pronunciation?] (28 November 1922 – 23 October 1997) was a Jewish theologian, historian, and diplomat.[1]

From 1951 to 1969, he served as an Israeli diplomat, including a tenure as Israel's Consul to Milan. He played a key role in securing diplomatic recognition for the young State of Israel.

Lapide was the author of more than 35 books, focusing on Jewish-Christian relations, theology, and history. He was married to Ruth Lapide, with whom he shared intellectual and scholarly pursuits.

Early life

[edit]Lapide was born in Vienna to a Jewish family as Erwin Pinchas Spitzer. During the Second World War, he managed to escape from Europe and reached Palestine. After the war, he studied Romance philology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Three Popes and the Jews

[edit]In 1967, Lapide published his book Three Popes and the Jews, which aimed to address the criticisms raised in Rolf Hochhuth's play The Deputy. The play accused Pope Pius XII of failing to respond adequately to the Holocaust during World War II.[2]

Lapide credited Pope Pius XII with leading efforts that saved hundreds of thousands of Jewish lives:

...the Catholic Church, under the pontificate of Pius XII was instrumental in saving at least 700,000, but probably as many as 860,000, Jews from certain death at Nazi hands.... These figures, small as they are in comparison with our six million martyrs whose fate is beyond consolation, exceed by far those saved by all other churches, religious institutions and rescue organizations combined.[3]

After analyzing the available evidence, he concluded:

Were I a Catholic, perhaps I should have expected the Pope, as the avowed representative of Christ on earth, to speak out for justice and against murder - irrespective of the consequences. But as a Jew, I view the Church and the Papacy as human institutions, as frail and fallible as all the rest of us. Frail and fallible, Pius had choices thrust upon him time and time again, which would have made a lesser man falter. The 261st Pope was, after all, merely the First Catholic, heir to many prejudices of his predecessors and shortcomings of his 500 million fellow believers. The primary guilt for the slaughter of a third of my people is that of the Nazis who perpetrated the holocaust. But the secondary guilt lies in the universal failure of Christendom to try and avert or, at least, mitigate the disaster; to live up to its own ethical and moral principles, when conscience cried out Save! whilst expediency counselled aloofness. Accomplices are all those countless millions who knew my brothers were dying, but yet chose not to see, refused to help and kept their peace. Only against the background of such monumental egotism, within the context of millennial Christian anti-Judaism, can one begin to appraise the Pope's wartime record. When armed force ruled well-nigh omnipotent, and morality was at its lowest ebb, Pius XII commanded none of the former and could only appeal to the latter, in confronting, with bare hands, the full might of evil. A sounding protest, which might turn out to be self-thwarting - or quiet, piecemeal rescue? Loud words - or prudent deeds? The dilemma must have been sheer agony, for which ever course he chose, horrible consequences were inevitable. Unable to cure the sickness of an entire civilization, and unwilling to bear the brunt of Hitler's fury, the Pope, unlike many far mightier than he, alleviated, relieved, retrieved, appealed, petitioned - and saved as best he could by his own lights. Who, but a prophet or a martyr could have done much more?[4]

Lapide also quoted Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s observation:

"He who begins by loving Christianity better than truth will proceed by loving his own sect or church better than Christianity, and end by loving himself better than all."[5]

Jesus and Lapide

[edit]In his dialogue with German Reformed theologian Jürgen Moltmann, Lapide states:

"On page 139 of his book The Church in the Power of the Spirit (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1977) it says: Through his crucifixion Christ has become the Saviour of the Gentiles. But in his parousia he will also manifest himself as Israel's Messiah.

I find this sentence an acceptable formula of reconciliation."[6]

Moltmann responds:

"Christendom can gain salvation only together with Israel. The Christians will one day be asked, Where are your Jewish brothers and sisters? The church will one day be asked, Where have you left Israel? For the sake of the Jew Jesus there is no ultimate separation between church and Israel. For the sake of the gospel there is provisionally, before the eschatological future, also no fusion. But there is the communal way of the hoping ones."[7]

In their joint declaration, Lapide and Moltmann acknowledge that the historical divergence between Christianity and Judaism is largely a result of artificial barriers that hinder reconciliation. Both affirm that Christianity and Judaism are parallel pilgrim paths leading to the same God.[8]

In another debate on the messianic interpretation of Isaiah 53 with Walter C. Kaiser Jr., Lapide argues that the people of Israel, collectively, serve as the expiatory lamb for humankind. He posits that God allows Israel to bear the burden of suffering, thereby enabling guilty humankind to survive. Kaiser, while recognizing the sacrificial theme in Lapide’s interpretation, notes that it bears similarities to the traditional evangelical Christian reading of Isaiah 53. However, he questions whether Israel as a collective guilt offering aligns with the text, especially when comparing Isaiah 29:13 with Isaiah 53:9:

He was assigned a grave with the wicked,

and with the rich in his death,

though he had done no violence,

nor was any deceit in his mouth

(Isaiah 53:9 NIV)

“These people come near to me with their mouth

and honor me with their lips,

but their hearts are far from me.

(Isaiah 29:13 NIV)

In response, Lapide contends that the selfless sacrifice of the Jewish prophets mirrors Israel’s role as a suffering servant, made acceptable through the imputed righteousness of God. He interprets Jesus’ suffering in the context of Isaiah 53 as a microcosm of Israel’s collective suffering.[9]

Ultimately, Lapide acknowledges Jesus as the Messiah of the Gentiles, a position he articulates more explicitly in his book The Resurrection of Jesus: A Jewish Perspective. Furthermore, he suggests that Jesus’ return in the parousia will reveal him as Israel’s Messiah. Lapide’s interfaith approach shapes his portrayal of Jesus and, similarly, informs his relatively nuanced and non-confrontational perspective on Paul.[10]

Works

[edit]- Der Prophet von San Nicandro. Vogt, Berlin 1963, Matthias-Grünewald-Verlag, Mainz 1986. ISBN 3-7867-1249-2

- Rom und die Juden. Gerhard Hess, Ulm 1967, 1997, 2005 (3.verb.Aufl.). ISBN 3-87336-241-4

- Three Popes and the Jews. 1967.

- Nach der Gottesfinsternis. Schriftenmissions-Verl., Gladbeck 1970.

- Auferstehung. Calwer, Stuttgart 1977, 1991 (6.Aufl.). ISBN 3-7668-0545-2

- Die Verwendung des Hebräischen in den christlichen Religionsgemeinschaften mit besonderer Berücksichtigung des Landes Israel. Diss. Kleikamp, Köln 1971.

- Er predigte in ihren Synagogen. Mohn, Gütersloh 1980, 2004 (8.Aufl.). ISBN 3-579-01400-5

- Am Scheitern hoffen lernen. Mohn, Gütersloh 1985, 1988. ISBN 3-579-01413-7

- Wer war schuld an Jesu Tod? Mohn, Gütersloh 1987, 1989, 2000 (4.Aufl.). ISBN 3-579-01419-6

- Ist das nicht Josephs Sohn? Jesus im heutigen Judentum. Mohn, Gütersloh 1988 . ISBN 3-579-01408-0

- Ist die Bibel richtig übersetzt? 2 Bd. Mohn, Gütersloh 2004. ISBN 3-579-05460-0

- Der Jude Jesus. Patmos, Düsseldorf 1979, 2003 (3.Aufl.). ISBN 3-491-69405-1

- Paulus zwischen Damaskus und Qumran. Mohn, Gütersloh 1993, 1995, 2001. ISBN 3-579-01425-0

- The Resurrection of Jesus: A Jewish Perspective [Paperback] Pinchas Lapide, Wipf & Stock Pub, 2002. ISBN 978-1579109080

- Jewish monotheism and Christian trinitarian doctrine: A dialogue [Paperback] Pinchas Lapide, Fortress Press (1981), ISBN 978-0800614058

Bibliography

[edit]- In the Spirit of Humanity, a portrait of Pinchas Lapide. In: German Comments. review of politics and culture. Fromm, Osnabrück 32.1993,10 (Oktober). ISSN 0722-883X

- Juden und Christen im Dialog. Pinchas Lapide zum 70. Geburtstag. Kleine Hohenheimer Reihe. Bd 25. Akad. der Diözese, Rottenburg-Stuttgart 1993. ISBN 3-926297-52-2

- Christoph Möhl: Sein grosses Thema: Die Juden und die Christen. In: Reformierte Presse. Fischer, Zürich 1997, 47.

- In memoriam Pinchas Lapide (1922–1997) - Stimme der Versöhnung. Ansprachen, Reden, Einreden. Bd 8. Kath. Akad., Hamburg 1999. ISBN 3-928750-56-9

- Ruth Lapide: Pinchas Lapide - Leben und Werk. In: Viktor E. Frankl: Gottsuche und Sinnfrage. Mohn, Gütersloher 2005, S.23. ISBN 3-579-05428-7

References

[edit]- ^ Deák, István (2001). Essays on Hitler's Europe. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803266308.

- ^ Three Popes and the Jews, Pinchas Lapide, Hawthorn, 1967

- ^ Three Popes and the Jews, Pinchas Lapide, Hawthorn, 1967, pp. 214-15

- ^ Three Popes and the Jews, Pinchas Lapide, p. 266-267, Hawthorn, 1967

- ^ Three Popes and the Jews, Hawthorn, 1967, p. 14

- ^ Pinchas Lapide, Jewish Monotheism and Christian Trinitarian Doctrine, p. 79, 1979 WIPF and STOCK Publishers

- ^ Pinchas Lapide, Jewish Monotheism and Christian Trinitarian Doctrine, p. 90, 1979 WIPF and STOCK Publishers

- ^ Pinchas Lapide, Jewish Monotheism and Christian Trinitarian Doctrine, pp. 91-93, 1979, WIPF and STOCK Publishers.

- ^ "Do The Messianic Prophecies of the Old Testament Point to Jesus or to Someone Else? - Part 5," by Dr. John Ankerberg, Dr. Walter Kaiser, and Dr. Pinchas Lapide.

- ^ Langton, Daniel (2010). The Apostle Paul in the Jewish Imagination. Cambridge University Press. pp. 86–89. ISBN 9780521517409.

- 20th-century Israeli philosophers

- 20th-century Jewish theologians

- 1922 births

- Diplomats from Vienna

- Jewish emigrants from Austria after the Anschluss to Mandatory Palestine

- 1997 deaths

- Commanders Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Israeli consuls

- Israeli diplomats

- Israeli male writers

- Israeli historians of religion

- Christian and Jewish interfaith dialogue