Parallelohedron

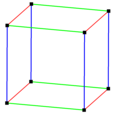

Cube |

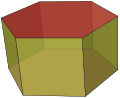

Hexagonal prism |

Rhombic dodecahedron |

Elongated dodecahedron |

Truncated octahedron |

In geometry, a parallelohedron or Fedorov polyhedron[1] is a convex polyhedron that can be translated without rotations to fill Euclidean space, producing a honeycomb in which all copies of the polyhedron meet face-to-face. Evgraf Fedorov identified the five types of parallelohedron in 1885 in his studies of crystallographic systems. They are the cube, hexagonal prism, rhombic dodecahedron, elongated dodecahedron, and truncated octahedron.

Each parallelohedron is centrally symmetric with symmetric faces, making it a special case of a zonohedron. Each parallelohedron is also a stereohedron, a polyhedron that tiles space so that all tiles are symmetric. The centers of the tiles in a tiling of space by parallelohedra form a Bravais lattice, and every Bravais lattice can be formed in this way. Adjusting the lengths of parallel edges in a parallelohedron, or performing an affine transformation of the parallelohedron, results in another parallelohedron of the same combinatorial type. It is possible to choose this adjustment so that the tiling by parallelohedra is the Voronoi diagram of its Bravais lattice, and so that the resulting parallelohedra become special cases of the plesiohedra.

The three-dimensional parallelohedra are analogous to two-dimensional parallelogons and higher-dimensional parallelotopes.

Definition and construction

[edit]A parallelohedron is defined to be a polyhedron whose translated copies meet face-to-face to fill space, forming a honeycomb.[2] The resulting honeycomb must be periodic, having a three-dimensional system of global symmetries, because each translation from a copy of the polyhedron to an adjoining copy must apply to all copies, forming a symmetry of the whole tiling.[3] For the same reason, the honeycomb is uniquely determined by the position of any one parallelohedron in it.[4] In order to meet face-to-face with another copy, each face of the polyhedron must correspond to a parallel face with the same shape but the opposite orientation. By a result of Hermann Minkowski, the shape of a parallelohedron is uniquely determined by the normal vectors and areas of these opposite face pairs. This implies that a parallelohedron must be centrally symmetric, because otherwise a point reflection of the polyhedron would produce a different shape with the same normal vectors and face areas, contradicting Minkowski's uniqueness theorem. Each face of a parallelohedron must also be centrally symmetric, to match its symmetric copy in the adjoining copy of the parallelohedron.[2]

These two properties of parallelohedra, having central symmetry and centrally symmetric faces, characterize a broader class of polyhedra, the zonohedra, so every parallelohedron is a zonohedron. In any zonohedron, the edges can be grouped into zones, systems of parallel edges of equal length. If one edge is selected from each zone, the Minkowski sum of the selected edges gives a translated copy of the zonohedron itself. All Minkowski sums of finite sets of line segments produce zonohedra; the segments forming a zonohedron in this way are called its generators. Unlike some other zonohedra, the parallelohedra can only have from three to six zones and, correspondingly, from three to six generators.[5]

Any zonohedron whose faces have the same combinatorial structure as one of the five parallelohedron is itself a parallelohedron. Any affine transformation of a parallelohedron will produce another parallelohedron of the same type.[2] One way to characterize the parallelohedra among all zonohedra is using belts. Senechal & Taylor (2023) define a belt of a zonohedron to be the cycle of faces that contain all parallel copies of one edge. The number of faces in any belt of any zonohedron must be even, and can be any even number greater than two. As Federov and many others showed, the parallelohedra are exactly the zonohedra all of whose belts consist of only four or six faces.[6]

Classification

[edit]By combinatorial structure

[edit]The five types of parallelohedron, and their most symmetric forms, are as follows.[2]

- A parallelepiped is generated from three line segments that are not all parallel to a common plane. Its most symmetric form is the cube, generated by three perpendicular unit-length line segments.[2] The tiling of space by the cube is the cubic honeycomb.[7]

- A hexagonal prism is generated from four line segments, three of them parallel to a common plane and the fourth not. Its most symmetric form is the right prism over a regular hexagon.[2] It tiles space to form the hexagonal prismatic honeycomb.[8]

- The rhombic dodecahedron is generated from four line segments, no two of which are parallel to a common plane. Its most symmetric form is generated by the four long diagonals of a cube.[2] It tiles space to form the rhombic dodecahedral honeycomb.[9] The Bilinski dodecahedron, another less-symmetric form of the rhombic dodecahedron, is notable for (like the symmetric rhombic dodecahedron) having all of its faces congruent; its faces are golden rhombi.[10]

- The elongated dodecahedron is generated from five line segments, with two triples of coplanar segments. It can be generated by using an edge of the cube and its four long diagonals as generators.[2]

- The truncated octahedron is generated from six line segments with four triples of coplanar segments. It can be embedded in four-dimensional space as the 4-permutahedron, whose vertices are all permutations of the counting numbers (1,2,3,4). In three-dimensional space, its most symmetric form is generated from six line segments parallel to the face diagonals of a cube.[2] The tiling of space generated by its translations has been called the bitruncated cubic honeycomb.[11]

| Name | Cube (parallelepiped) |

Hexagonal prism Elongated cube |

Rhombic dodecahedron | Elongated dodecahedron | Truncated octahedron |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

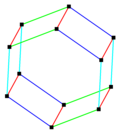

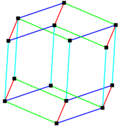

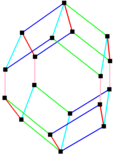

| Images (colors indicate parallel edges) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Number of generators | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Vertices | 8 | 12 | 14 | 18 | 24 |

| Edges | 12 | 18 | 24 | 28 | 36 |

| Faces | 6 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 14 |

| Tiling |

|

|

|

|

|

| Tiling name and Coxeter–Dynkin diagram | Cubic |

Hexagonal prismatic |

Rhombic dodecahedral |

Elongated dodecahedral | Bitruncated cubic |

By symmetries and Bravais lattices

[edit]The lengths of the segments within each zone can be adjusted arbitrarily, independently of the other zones. Doing so extends or shrinks the corresponding edges of the parallelohedron, without changing its combinatorial type or its property of tiling space. As a limiting case, for a parallelohedron with more than three parallel classes of edges, the length of one of these classes can be adjusted to zero, producing a different parallelohedron of a simpler form, with one fewer zone. Beyond the central symmetry common to all zonohedra and all parallelohedra, additional symmetries are possible with an appropriate choice of the generating segments.[12]

When further subdivided according to their symmetry groups, there are 22 forms of the parallelohedra. For each form, the centers of its copies in its honeycomb form the points of one of the 14 Bravais lattices. Because there are fewer Bravais lattices than symmetric forms of parallelohedra, certain pairs of parallelohedra map to the same Bravais lattice.[12]

By placing one endpoint of each generating line segment of a parallelohedron at the origin of three-dimensional space, the generators may be represented as three-dimensional vectors, the positions of their opposite endpoints. For this placement of the segments, one vertex of the parallelohedron will itself be at the origin, and the rest will be at positions given by sums of certain subsets of these vectors. A parallelohedron with vectors can in this way be parameterized by coordinates, three for each vector, but only some of these combinations are valid (because of the requirement that certain triples of segments lie in parallel planes, or equivalently that certain triples of vectors are coplanar) and different combinations may lead to parallelohedra that differ only by a rotation, scaling transformation, or more generally by an affine transformation. When affine transformations are factored out, the number of free parameters that describe the shape of a parallelohedron is zero for a parallelepiped (all parallelepipeds are equivalent to each other under affine transformations), two for a hexagonal prism, three for a rhombic dodecahedron, four for an elongated dodecahedron, and five for a truncated octahedron.[13]

History

[edit]The classification of parallelohedra into five types was first made by Russian crystallographer Evgraf Fedorov, as chapter 13 of a Russian-language book first published in 1885, whose title has been translated into English as An Introduction to the Theory of Figures.[14] Federov was working under an incorrect theory of the structure of crystals, according to which every crystal has a repeating structure in the shape of a parallelohedron, which in turn is formed from one or more molecules that all take the same shape (a stereohedron). This theory was falsified by the 1913 discovery of the structure of halite (table salt) which is not partitioned into separate molecules, and more strongly by the much later discovery of quasicrystals.[6]

Some of the mathematics in Federov's book is faulty; for instance it includes an incorrect proof of a lemma stating that every monohedral tiling of the plane is periodic,[15] proven to be false in 2023 as part of the solution to the einstein problem.[16] In the case of parallelohedra, Fedorov assumed without proof that every parallelohedron is centrally symmetric, and used this assumption to prove his classification. The classification of parallelohedra was later placed on a firmer footing by Hermann Minkowski, who used his uniqueness theorem for polyhedra with given face normals and areas to prove that parallelohedra are centrally symmetric.[2]

Related shapes

[edit]In two dimensions the analogous figure to a parallelohedron is a parallelogon, a polygon that can tile the plane edge-to-edge by translation. There are two kinds of parallelogons: the parallelograms and the hexagons in which each pair of opposite sides is parallel and of equal length.[17]

There are multiple non-convex polyhedra that tile space by translation, beyond the five Federov parallelohedra.[6][18] These are not zonohedra and need not be centrally symmetric. For instance, some of these can be obtained from a rhombic triacontahedron by replacing certain triples of faces by indentations. According to a conjecture of Branko Grünbaum, for every polyhedron that is topologically a sphere and can tile space by translation, it is possible to group its faces into patches (unions of connected subsets of faces) so that the combinatorial structure of these patches is the same as the combinatorial structure of the faces of one of the five Federov parallelohedra. This conjecture remains unproven.[6]

In higher dimensions a convex polytope that tiles space by translation is called a parallelotope. There are 52 different four-dimensional parallelotopes, first enumerated by Boris Delaunay (with one missing parallelotope, later discovered by Mikhail Shtogrin),[19] and exactly 110,244 types in five dimensions.[20] Unlike the case for three dimensions, not all of them are zonotopes. 17 of the four-dimensional parallelotopes are zonotopes, one is the regular 24-cell, and the remaining 34 of these shapes are Minkowski sums of zonotopes with the 24-cell.[21] A -dimensional parallelotope can have at most facets, with the permutohedron achieving this maximum.[5]

Every parallelohedron is a stereohedron, a convex polyhedron that tiles space in such a way that there exist symmetries of the tiling that take any tile to any other tile. A plesiohedron is a related class of three-dimensional space-filling polyhedra, formed from the Voronoi diagrams of periodic sets of points (of a more general type than the lattices).[17] The Voronoi diagram of a lattice produces a tiling of space by parallelohedra,[20] but not every parallelohedron and its tiling can be generated in this way: for a parallelohedron to be a plesiohedron, it is required that each vector from the center of the parallelohedron to the center of a face be perpendicular to the face.[2] However, as Boris Delaunay proved in 1929,[22] every parallelohedron can be made into a plesiohedron by an affine transformation.[2] He also proved the same fact for four-dimensional parallelohedra,[17] and it has been proven as well for five dimensions,[20] but this remains open in higher dimensions.[5][17][20] Some other three-dimensional plesiohedra are not parallelohedra. The tilings of space by plesiohedra have symmetries taking any cell to any other cell, but unlike for the parallelohedra, these symmetries may involve rotations, not just translations.[17]

See also

[edit]- Keller's conjecture, on tilings by translated copies of cubes and hypercubes that are not required to be face-to-face

References

[edit]- ^ Hargittai, Istvan (November 1998). "Symmetry in crystallography" (PDF). Acta Crystallographica, Section A. 54 (6): 697–706. Bibcode:1998AcCrA..54..697H. doi:10.1107/s0108767398006709.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Alexandrov, A. D. (2005). "8.1 Parallelohedra". Convex Polyhedra. Springer. pp. 349–359.

- ^ Engel, P. (December 2015). "On Fedorov's parallelohedra – a review and new results". Crystal Research and Technology. 50 (12): 929–943. Bibcode:2015CryRT..50..929E. doi:10.1002/crat.201500257.

- ^ Dolbilin, N. P. (2012). "Parallelohedra: a retrospective and new results". Transactions of the Moscow Mathematical Society. 73. Translated by Khukhro, E.: 207–220. doi:10.1090/s0077-1554-2013-00208-3. MR 3184976.

- ^ a b c Dienst, Thilo. "Fedorov's five parallelohedra in R3". University of Dortmund. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ^ a b c d Senechal, Marjorie; Taylor, Jean E. (March 2023). "Parallelohedra, old and new". Acta Crystallographica Section A. 79 (3): 273–279. doi:10.1107/S2053273323001444. PMID 36999623.

- ^ Coxeter, H. S. M. (1958). "Close-packing and froth". Illinois Journal of Mathematics. 2 (4B): 746–758. doi:10.1215/ijm/1255448337. MR 0102053.

- ^ Delaney, Gary W.; Khoury, David (February 2013). "Onset of rigidity in 3D stretched string networks". The European Physical Journal B. 86 (2): 44. Bibcode:2013EPJB...86...44D. doi:10.1140/epjb/e2012-30445-y.

- ^ Matteo, Nicholas (2016). "Two-orbit convex polytopes and tilings". Discrete & Computational Geometry. 55 (2): 296–313. arXiv:1403.2125. doi:10.1007/s00454-015-9754-2. MR 3458600.

- ^ Grünbaum, Branko (2010). "The Bilinski dodecahedron and assorted parallelohedra, zonohedra, monohedra, isozonohedra, and otherhedra". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 32 (4): 5–15. doi:10.1007/s00283-010-9138-7. hdl:1773/15593. MR 2747698. S2CID 120403108.

- ^ Thuswaldner, Jörg; Zhang, Shu-qin (2020). "On self-affine tiles whose boundary is a sphere". Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. 373 (1): 491–527. arXiv:1811.06718. doi:10.1090/tran/7930. MR 4042883.

- ^ a b Tutton, A. E. H. (1922). Crystallography and Practical Crystal Measurement, Vol. I: Form and Structure. Macmillan. p. 567.

- ^ Dolbilin, Nikolai P.; Itoh, Jin-ichi; Nara, Chie (2012). "Affine classes of 3-dimensional parallelohedra – their parametrization". In Akiyama, Jin; Kano, Mikio; Sakai, Toshinori (eds.). Computational Geometry and Graphs - Thailand-Japan Joint Conference, TJJCCGG 2012, Bangkok, Thailand, December 6-8, 2012, Revised Selected Papers. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 8296. Springer. pp. 64–72. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-45281-9_6. ISBN 978-3-642-45280-2.

- ^ Fedorov, E. S. (1885). Начала учения о фигурах [Introduction to the Theory of Figures] (in Russian).

- ^ Senechal, Marjorie; Galiulin, R. V. (1984). "An introduction to the theory of figures: the geometry of E. S. Fedorov". Structural Topology (in English and French) (10): 5–22. hdl:2099/1195. MR 0768703.

- ^ Roberts, Siobhan (March 29, 2023). "Elusive 'Einstein' solves a longstanding math problem". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e Grünbaum, Branko; Shephard, G. C. (1980). "Tilings with congruent tiles". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. New Series. 3 (3): 951–973. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-1980-14827-2. MR 0585178.

- ^ Ranganathan, S.; Lord, E. A. (September 2008). "Parallelohedra and topological transitions in cellular structures". Philosophical Magazine Letters. 88 (9–10): 703–713. Bibcode:2008PMagL..88..703R. doi:10.1080/09500830802112173.

- ^ Engel, P. (1988). Hargittai, I.; Vainshtein, B. K. (eds.). "Mathematical problems in modern crystallography". Crystal Symmetries: Shubnikov Centennial Papers. Computers & Mathematics with Applications. 16 (5–8): 425–436. doi:10.1016/0898-1221(88)90232-5. MR 0991578. See in particular p. 435.

- ^ a b c d Garber, Alexey (February 2025). "Voronoi conjecture for five-dimensional parallelohedra". Inventiones Mathematicae. arXiv:1906.05193. doi:10.1007/s00222-025-01325-0.

- ^ Deza, Michel; Grishukhin, Viacheslav P. (2008). "More about the 52 four-dimensional parallelotopes". Taiwanese Journal of Mathematics. 12 (4): 901–916. arXiv:math/0307171. doi:10.11650/twjm/1500404985. MR 2426535.

- ^ Austin, David (November 2013). "Fedorov's five parallelohedra". AMS Feature Column. American Mathematical Society.