Paleobiota of the Posidonia Shale

| Part of a series on |

| Paleontology |

|---|

|

|

Paleontology Portal Category |

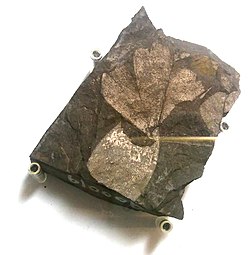

The Sachrang Formation or "Posidonienschiefer" Formation (common name the "Posidonia Shale") is a geological formation of southwestern Germany, northern Switzerland, northwestern Austria, southeast Luxembourg and the Netherlands, that spans about 3 million years during the Early Jurassic period (early Toarcian stage). It is known for its detailed fossils, especially marine biota, listed below.[1] Composed mostly of black shale, the formation is a Lagerstätte, where fossils show exceptional preservation (including exquisite soft tissues), with a thickness that varies from about 1 m to about 40 m on the Rhine level, being on the main quarry at Holzmaden between 5 and 14 m.[1] Some of the preserved material has been transformed into the fossil hydrocarbon jet which, especially jet derived from wood remains, is used for jewelry.[2] The exceptional preservation seen in the Posidonia Shale has been studied since the late 1800s, finding that a cocktail of chemical and environmental factors led to such an impressive preservation of the marine fauna.[2] The most common theory is that changes in the oxygen level, where the different anoxic events of the Toarcian left oxygen-depleted bottom waters, stopped scavengers from consuming the dead bodies.[3]

Biological interactions

[edit]

- The "Monotis"-Dactylioceras bed shows an accumulation of the bivalves Meleagrinella substriata and the ammonite Dactylioceras, that were the most abundant representatives of its group on the Altdorf region, and were probably washed to near epicontinental waters by a rapid event, or as result of a large succession of events.[4] This assemblage has been compared with modern Brazilian coastal mangroves and also linked to tsunami events.[5]

- Several empty ammonite shells from Holzmaden have been found with associated decapods inside.[6] This includes a possible member of the genus Paleastacus inside a chamber of a Harpoceras.[6] This decapod is related to the family Erymidae, which are considered to be possible bottom-dweller carnivores or carrion feeders.[6] The associated fossil has several spherical structures that had been interpreted as decapod coprolites, implying that the animal lived for a long period within the shell.[6] More recent studies had recovered new data about the inquilinism of decapods inside ammonites, this time, however, recovering three eryonoids together within a body chamber.[7] The eryonoids most likely used the ammonoid as some kind of shelter, possibly due to the shell being an ideal location to molt, protection against predators, a source of food or that the shell was used as a long-term shelter.[7] One key aspect found was that the muddy bottom was not suitable for burrowing, implying that the decapods inhabited a different shelter due to being unable to make their own.[7] Other biota are found related to the decayed ammonite shells, such as serpulid annelids and bivalves, creating what was denominated as "benthic islands".[6]

- Beyond trace fossils, several vertebrate specimens show associations with crustacean exoskeletal remains such as GPIT-PV-31586 and SMNS 58389 (Pachycormus macropterus) with necrophagous interaction as well SMNS 55934 (Stenopterygius quadriscissus) or SMNS 95401 (Metopacanthus sp.).[8]

- The genus Clarkeiteuthis and its predatory behaviour, found associated with fishes of the genus Leptolepis.[9] Based on the position of prey and predator, it was suggested that the cephalopods caught and killed the fishes while the schools were still in well-oxygenated waters and then descended into oxygen-depleted water layers where the cephalopod suffocated and died attached to its prey.[9] The cephalopods’ arms were contracted over the fish, likely killing it quickly by cutting its spine.[9]

- Several Geotheutis have been reported with eumelanin preserved along with their ink sacs.[10]

- A specimen of Jeletzkyteuthis found in Ohmden has appeared predating a Parabelopeltis. The association of these 2 genera shows the predatory behaviour of this group when its members lived in epicontinental seas, which is rather different than extant Vampyromorphs.[11]

- A pabulite (fossilized meal which never entered the digestive tract) was recovered from Holzmaden, being composed of an associated Passaloteuthis laevigata with its arms embracing an exuvia of a crustacean.[12] The belemnnite itself can be seen as the remnant of a failed predation attempt from a Hybodus, corroborating a possible tropic chain.[12]

- One of the most complex organism interactions on the Posidonia Shale were the crinoid megarafts that grouped a wide variety of animals, creating large floating ecosystems.[13] The largest megaraft found measured 18 metres (59 ft), and is based on an Agathoxylon trunk, where different animals were attached.[13] The first attached animals would have been the growing community of oysters, bivalves and crinoids, that would add a small weight to the raft (about 800 kilograms (1,800 lb)).[13] The presence of these megarafts were in part possible due to the absence of marine wood worms which destroy tree logs in less than 3 years along with the absence of modern raft wood predators (that appeared on the Bathonian). These rafts could last up to 5 years, which is the main reason the crinoids attached were able to reach huge sizes.[13] These rafts were likely also essential to distribute animals along sea basins.[13] Seirocrinus & Pentacrinites were some of the main crinoid colonizers of the floating rafts.[14] Seirocrinus is the main representative of the pelagic crinoids, being among the longest animals known, reaching 26 m long in the largest documented specimen.[14] The ecology of the genus is widely known, with it being known that the smallest stems were among the first animals to colonize the rafts, with at least 2 generations of crinoids found per raft, where the hydrodynamic changes of the log influenced the settlement of the crinoids.[14] It is believed that Seirocrinus underwent seasonal reproduction linked to monsoonal conditions that sent new logs to the sea.[14] The large crinoids would have feed on pelagic micronutrients, and after the log fell to the bottom, all of the colony would have died.[14]

- Thoracic barnacles of the genus Toarcolepas became the oldest epiplanktonic barnacle known in the fossil record, probably motivated by the appearance of the giant crinoid rafts. It has been found in situ associated with fossil wood.[15]

- The shark Hybodus includes specimens with gastric contents full of belemnnite fragments.[16] This implies active predatory behaviour by the genus towards several kinds of belemnnites, such as Youngibelus.[16]

- A speiballen (a regurgitated mass composed of indigestible stomach contents) had been found in the Holzmaden quarry.[17] The speiballen measures 285 mm in length with a diameter of 160 mm, and consists of 4 members of the genus Dapedium (Dapediidae) and a jaw identified as Lepidotes (Semionotidae).[17] The maker of this speiballen has been suggested to be a shark like Hybodus, an actinopterygian or a marine reptile.[17]

- A specimen of Pachycormus has been found with stomach contents that include hooks similar to the ones found on genera like Clarkeiteuthis.[18]

- Another specimen of Pachycormus macropterus preserves an ammonite inside its gut, likely swallowed by accident and directly responsible for the fish’s death.[19]

- SMNS 51144 (Saurostomus esocinus) was found with Chondrites sp. burrows in the abdominal cavity, what indicates a possible opportunistic scavenger. Other Chondrites sp. includes SMNS 17500 and MHH 1981/25 (Stenopterygius uniter) that either suggest the ichthyosaurs were preserved immediately below one such bioturbation horizon or scavenger association.[8]

- The known specimens of Toarcocephalus are evidence of successful predation events, as the head of one was isolated, likely as product of a decapitation, with another preserved within a regurgitated mass.[20]

- One of the most emblematic finds of the formation is that of a mother Stenopterygius giving birth to live young. While specimens have been found with embryos, the bones of these embryos are scattered partly beyond the body limits of the mother.[21] There have been various theories about this scenario: either the bones of embryos had been deposited before the body of the adult went to the sea floor, or in the ichthyosaurs’ last moments where it sank to the bottom and may have given untimely birth to some of the foetuses, and finally another option follows post mortem hydrostatic pressure being too high to be prevented by the body, exploding or expelling its embryos.[22]

- The specimen SMNS 53363 (Eurhinosaurus?) from Aichelberg was found with two encrusted large oysters (Liostrea) on the right pterygoid, considered to be part of a reef stage over bones.[8]

- SMNS 80234 (Stenopterygius quadriscissus) represents another female with embryos, yet also shows ribs broken perimortem that may represent either intraspecific aggression or a predation attempt. This specimen has several taxa associated: ammonite aptychi, two ophiuroids (Sinosura brodiei) and a articulated echinoid (Diademopsis crinifera) indicate a short-lived deadfall community.[8]

- SMNS 81841 (Stenopterygius quadriscissus) represents one of the clearest examples of deadfall communities described in the formation: the skeleton is associated with serpulids surrounded by a mass of disarticulated ophiuroid remains, indeterminate echinoid tests, an isolated crinoid ossicle, the byssate bivalve Oxytoma inaequivalvis, the pectinid Propeamussium pumilus, Eopecten strionatis, Plagiostoma sp., Meleagrinella sp., "Cucullaea" muensteri, with the genera Parainoceramya dubia and Liostrea associated with the carcass.[23] As many of these bivalves show overgrowth the community likely persisted for some time.[23] Fossil traces of Gastrochaenolites isp. attributed to mechanical bivalve borers are abundant implicating prolonged exposure of the skeleton on the seafloor.[23]

- SMNS 81719 (Stenopterygius uniter) includes Liostrea, Propeamussium pumilus, Plagiostoma sp. and Parainoceramya dubia, with other invertebrates found (?) not being part of the deadfall community, such as several ammonites and Parainoceramya valves, being stratigraphically below the specimen.[8] This specimen includes also traces of scavenging activity, possibly by crustaceans.[8]

- SMNS 80113, (Stenopterygius triscissus) was found populated by Parainoceramya, a specimen of Eopecten strionatis and an unexpected specimen of the small infaunal lucinid Mesomiltha pumila, equivocal evidence for the sulfophilic stage.[8]

- Local ichthyosaur soft tissues include skin enough well preserved to infer coloration and appearance on the living animal, as well evidence for homeothermy and crypsis.[24]

- Gut contents of the local pterosaurs are known: Campylognathoides preserves hooks of the coleoid Clarkeiteuthis (therefore being the one of the few teuthophagous pterosaurs), while Dorygnathus preserves remains of Leptolepis.[25]

Microbial activity

[edit]Non-fenestrate stromatolite crusts formed in aphotic deep-water environments during intervals of very low sedimentation are recovered in places such as Teufelsgraben, Hetzles.[26] The stromatolites of this region have evidence of live on a deeper shelf environment with a quietwater deposit which suffered repeated phases of stagnant bottom waters, where a depth water habitat developed, probably at more than 100 meters depth.[26] There is a thin, southern widespread stromatolite crust on the top of the Sachrang Formation, called "Wittelshofener Bank", that has made researchers rethink the depth of the major southern basin of the formation, where the absence of phototrophic calcareous benthic organisms (probably due to the lack of light) shows the depth of the basin.[26] On the "Wittelshofener Bank" there is also the only occurrence of ooids, presumably formed in the same deep-water environment.[26]

Color key

|

Notes Uncertain or tentative taxa are in small text; |

| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Possible traces of Microbial Activity |

Probably related with archaeal activity.[26] Although Frutexites is a cryptic microfossil and an important element of many deep water stromatolites, with an inorganic origin proposed it was interpreted as dendritic shrubs of purely inorganic growth of aragonitic crystals, but it also resembles shrubs of the cyanobacteria Angulocellularia.[26] In the Posidonia Shale a cryptoendopelitic mode of life is assumed, being only possible for heterotrophic bacteria or fungi.[26] As seen in the stromatolites of the Posidonia Shale, Frutexites acted mainly as a dweller or secondary binder of the deep-water stromatolites, not as their major constructor.[26] |

Cyanobacteria

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Crypt laminites |

A cyanobacteria, member of the family Oscillatoriales. Girvanella is almost rock-forming in the lower and upper levels, and is very common, but can only rarely be detected in the bituminous clay marl slate due to preservation reasons.[27] |

Rhizaria

[edit]Foraminifera

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, type member of the family Ammodiscinae inside Ammodiscina. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of Psammosphaerinae inside the family Psammosphaeridae. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of Vaginulinidae inside the family Vaginulinida (Lagenina). |

| |

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of Vaginulinidae inside the family Vaginulinida (Lagenina). |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, type member of Cornuspiridae inside the family Cornuspirida (Lagenina). Round-spiral shell morphology |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of the family Cornuspirinae inside Cornuspiridae. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of Nodosariidae inside the family Nodosariacea (Lagenina). |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of Vaginulinidae inside the family Vaginulinida (Lagenina). |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, type member of Frondiculariinae inside the family Nodosariidae (Lagenina). |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of the family Usbekistaniinae inside Ammodiscidae. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, type member of Ichthyolariidae inside the family Lagenina. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of the family Involutinidae inside Involutinae. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of Vaginulinidae inside the family Vaginulinida (Lagenina). |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, type member of Lingulininae inside the family Nodosariidae (Lagenina). |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of Marginulininae inside the family Vaginulinida (Lagenina). |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of Nodosariidae inside the family Nodosariacea (Lagenina). |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of Vaginulinidae inside the family Vaginulinida (Lagenina). |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of Nodosariidae inside the family Nodosariacea (Lagenina). |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of Ceratobuliminidae inside the family Robertinida. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of Lenticulininae inside the family Vaginulinida (Lagenina). |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of the family Spiroplectammininae inside Spiroplectamminidae. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, member of the family Involutinidae inside Involutinae. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A benthic foraminiferan, type member of Vaginulinidae inside the family Vaginulinida (Lagenina). |

Dinoflagellata

[edit]Dinoflagellate cysts

[edit]The evolutionary burst of the Toarcian dinoflagellates led the first appearance and rapid radiation of the Phallocystaceae (Susainium, Parvocysta, Phallocysta, Moesiodinium and related forms).[30] This occurred at the time of a widespread Lower Toarcian bituminous anoxia-derived shale, which is recovered from the Posidonienschiefer, Pozzale, Italy, Asturias, Spain, Bornholm, Denmark, the Lusitanian Basin of Portugal, the Jet Rock Formation in Yorkshire and to the "Schistes Carton" in northern France. Whether there is a causal connection in this co-occurrence of Phallocystaceae and bituminous facies is a problem still to be resolved. This family has its acme in diversity and quantity in the latest Toarcian and became less important in the Aalenian.[30]

| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst from the family Apodiniaceae. An ectoparasitic dinoflagellate, whose hosts are normally tunicates |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst from the family Scriniocassiaceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst from the family Scriniocassiaceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst from the family Comparodiniaceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst from the family Scriniocassiaceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst, type member of Luehndeoideae. Luehndea spinosa is common in the middle layers of the lower Sachrang Formation, while restricted to certain areas in younger ones.[34] |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst, type member of Mancodiniaceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst, member of Dinophyceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst, member of Dollidiniaceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst from the family Heterocapsaceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst from the family Heterocapsaceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst, member of Dinophyceae of the family Nannoceratopsiaceae. In the Lias Epsilon Interval (Lowermost Toarcian), most of the assemblages are dominated by Nannoceratopsis gracilis. Nannoceratopsis senex becomes highly abundant until the uppermost Tenuicostatum.[34] |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst from the family Scriniocassiaceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst from the family Gonyaulacaceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst from the family Heterocapsaceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst from the family Heterocapsaceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst from the family Phallocysteae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A dinoflagellate cyst from the family Comparodiniaceae. |

Algae

[edit]The Posidonia Shale preserves an abundant variety of algae, such as the genus of colonial green algae Botryococcus, or the unicellular algal bodies Tasmanites, and other small examples. Algae are a good reference for changes on the oxygen conditions along the Toarcian.[37]

Algal acritarchs

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Cysts |

An acritarch probably of algal origin. Related to open shelf deposits |

||

|

|

Cysts |

An acritarch probably of algal origin. Its fossils indicate nearshore or estuarine to shallow lagoon and/or slightly brackish-water environments. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

An acritarch probably of algal origin. Related to open shelf deposits |

||

|

|

Cysts |

An acritarch probably of algal origin. It is abundant in most of the samples studied from the Sachrang Formation, being nearly the 50% of the acritarch fraction on some locations. |

Haptophyta

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Coccoliths |

Type member of the family Biscutaceae inside Parhabdolithaceae. |

||

|

|

Coccoliths |

A member of the family Watznaueriaceae inside Watznaueriales. |

||

|

|

Coccoliths |

Member of the family Calyculaceae inside Parhabdolithaceae. |

||

|

|

Coccoliths |

A member of the family Chiastozygaceae inside Eiffellithales. |

||

|

|

Coccoliths |

Member of the family Parhabdolithaceae inside Stephanolithiales. |

||

|

|

Coccoliths |

Member of the family Biscutaceae inside Parhabdolithaceae. |

||

|

|

Coccoliths |

A member of the family Watznaueriaceae inside Watznaueriales. |

||

|

|

Coccoliths |

A member of the family Parhabdolithaceae inside Stephanolithiales. The abundance drop of M. jansae further characterises the T-OAE perturbation, where it becomes the dominant genus in most of the Saxony Basin. |

||

|

|

Coccoliths |

Member of the family Parhabdolithaceae inside Stephanolithiales. |

||

|

|

Coccoliths |

incertae Sedis |

||

|

|

Coccoliths |

Type member of the family Schizosphaerellaceae inside Parhabdolithaceae. Towards the Pliensbachian-Toarcian extincion this genus decreases in abundance and size. |

||

|

|

Coccoliths |

Member of the family Biscutaceae inside Podorhabdales. |

||

|

|

Coccoliths |

Member of the family Biscutaceae inside Podorhabdales. |

||

|

|

Coccoliths |

A member of the family Chiastozygaceae inside Eiffellithales. |

Chlorophyta

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Cysts |

Type member of the family Botryococcaceae inside Trebouxiales. This genus usually inhabits freshwater or deltaic environments. |

| |

|

|

Cysts |

A member of Prasinophyceae. A genus common in green clays and other upper strata of the formation. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A member of the family Pyramimonadales inside Prasinophyceae. Often found in basinal deposits. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A member of Gonyaulacaceae inside Dinophyceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A member of the Prasinophyceae. Often found in basinal deposits. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A member of the family Halosphaeraceae inside Chlorodendrales. Often found in basinal deposits. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A member of the Prasinophyceae. Often found in basinal deposits. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A member of the Prasinophyceae. Often found in basinal deposits |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A member of the Prasinophyceae. Often found in basinal deposits |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A member of Peridiniaceae inside Dinophyceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A member of Prasinophyceae. It is the main genus present within silt and sand horizons, tending to be absent in shale layers. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A member of Dinophyceae. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A member of Prasinophyceae. A genus common in green clays and other upper strata of the formation. |

||

|

|

Cysts |

A member of the Prasinophyceae. Often found in basinal deposits |

Fungi

[edit]Fungal spores, hyphae and indeterminate remains are a rare element of the otherwise open marine deposits of the Posidonienschiefer formation, but were recovered at Dormettingen.[46] These fungal remains are composed mostly of indeterminate spores and indicate oxygenated environments and suitable transportation by rivers.[46]

Incertae sedis

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Fungal patches in ammonite shells and belemnite rostra |

A marine parasitoid fungus of uncertain relationship, linked with shells of marine invertebrates. The extant Ostracoblabe implexa is usually found associated with bivalve shells as an external parasitoid. Beyond this genus, other fungal remains include indeterminate endolithic fungi linked with microbial mats. |

Ichnofossils

[edit]The major ichnological analyses of the Posidonian Shale come from Dotternhausen/Dormettingen, where the ichnogenus Phymatoderma formed the so-called Tafelfleins and Seegrasschiefer.[48] The Tafelflein bed was deposited under anoxic bottom and pore water, where a recover of oxygen allow the Phymatoderma-producers return.[48] The two organic-rich layers (Tafelfleins and Seegrasschiefer) are characterized by the dense occurrence of trace fossils such as Chondrites and Phymatoderma, done episodically due to the fall of the oxygen levels.[48] The coeval more nearshore Swiss deposits referred Posidonian Shale (Rietheim Member) hosted similar trace fossils to those recovered on SW Germany.[48] Ichnofossils in this setting apparently evolved faster to more oxic-to-dysoxic bottom waters.[48] At Unken, laminated deposits of red limestone suggest well oxygenated active waters (as they lack shale), where high amounts of Chondrites are found.[40]

| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Made By | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Burrowing and track ichnofossils |

|

| |

|

|

Borings on bones |

|

| |

|

|

Burrowing and track ichnofossils. |

|

| |

|

|

Burrowing and track ichnofossils. |

|||

|

|

Burrowing and track ichnofossils |

|

| |

|

|

Burrowing and track ichnofossils |

|

| |

|

|

Burrowing and track ichnofossils. |

|

|

Invertebrata

[edit]Porifera

[edit]In the non-bituminous facies located on Obereggenen im Breisgau (Shore of the Black Forest High), especially the lower semicelatum subzone, pyritized individual needles of silica sponges (Demospongiae and Hexactinellida) are found, rarely on pelagic layers to very often on the low depth marine deposits.[27] They are usually associated with radiolarian stone cores. In Dusslingen and Reutlingen, these sponge needles are sometimes barytized in phosphorites of the Haskerense subzone and are much more common here than in any other zone of the Lower Toarcian. These needles are absent in the bituminous horizons of the entire Lower Toarcian.[27] Increased amounts of sponge needles (dominated by Hexactinellida) are also found on the arenaceous facies of the nearshore unit that is the Unken member, being the only section if its region hosts them, probably due to be an active and well oxygenated bottom.[40] The location of this member as a possible bay on the south of the vindelician land probably allow to the development of more pre-Toarcian AOE conditions, hence the presence of biota otherwise rare on bituminous layers.[40]

Annelida

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Isolated Tubes |

A sessile, marine annelid tube worm of the family Serpulidae. Presumably these specimens have fallen from their growth areas.[27] |

| |

|

|

Scolecodonts |

A polychaete of the family Dorvilleidae inside Eunicida. Eunicidan species with prionognath jaws, absent in bituminous layers |

Lophophorata

[edit]Bryozoa

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Colonial imprints |

A Bereniceidae Stenolaematan. The colonies’ form is extremely characteristic, forming curved fans |

||

|

|

Colonial imprints |

A Oncousoeciidae Stenolaematan. Colonies consists of bands that are the same width throughout their entire extent and can branch. |

|

Brachiopoda

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

A Lingulidae rhynchonellatan. Associations of bioturbating infauna are dominated in certain sections by Palaeonucula/Lingula aggregations, developed under longer-term oxygenated conditions within the substrate and bottom waters.[57] |

||

|

|

Shells |

A Discinidae rhynchonellatan. This genus was found to have a planktotrophic larval stage that adapted while growing to the local redox boundary. When this fluctuated near the sediment–water interface and oxygen availability prevailed, it allowed benthic colonization. It is found in associations with Grammatodon and Pseudomytiloides.[57] |

||

|

|

Shells |

A Rhynchonellidae rhynchonellatan. Found associated with Plicatula in long-term well-oxygenated conditions within the substrate and bottom waters.[57] |

||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

Mollusca

[edit]Bivalvia

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dotternhausen |

Shells |

|||

|

All the Formation |

Shells |

A posidoniid ostreoidan. It is the type fossil of the Sachrang Formation. Originally it was named "Posidonia bronni", thought to be a new genus, and the strata were denominated the Posidonia layers after it. Years later it turned out to be a junior synonym of Bositra, and thus it was reassigned. However, the name of the layers was retained. The habitat and mode of life of Bositra has been debated for more than a century. There have been different interpretations, such as a pseudoplanktonic organism,[59] a benthic organism living on the open marine floor, where it was the main inhabitant of the basinal settings, and a hybrid mode, where it had a life cycle with holopelagic reproduction controlled by changes in oxygen levels, and even a chemosymbiotic lifestyle with the large crinoid rafts being the main “safe havens” to evade anoxic events. Various hypotheses along the years led to a large study in 1998, where the size/frequency distribution, the density of growth through lines related to the shell size and the position of the redox boundary by total organic carbon diagrams revealed that Bositra probably had a benthic mode of life.[60] |

| |

|

|

Shells |

A pectinoid scallop. The presence of this genus along endobenthic and epibenthic bivalves, which are absent farther up the section, suggest a delayed overstepping of anoxic bottom waters on the Altdorf High.[61] |

||

|

|

Shells |

| ||

|

|

Shells |

A cucullaeid clam. |

||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

A bakevelliid mud oyster. |

||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

A Grammatodontinae clam. This genus had a lecithotrophic and planktotrophic larval development.[57] |

||

|

|

Shells |

| ||

|

|

Shells |

| ||

|

|

Shells |

| ||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

An inoceramid clam. |

||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

An inoceramid clam. |

| |

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

| ||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

A plicatulid mud scallop. |

||

|

|

Shells |

An oxytomid scallop. Found mostly in the "Dactylioceras-Monotis-Bank", a deposit derived from large scale tectonic events on the Bohemian coastline |

||

|

|

Shells |

A propeamussiid mud scallop. |

| |

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

An inoceramid clam. Being the second most common genus of bivalve in the Formation, it has been subject to several studies in regards to its ecological niche, similar to Bositra. Several opinions include a pseudoplanktonic-only organism able to live in the open sea, or a benthic-only organism. Within the 1998 evaluation with Bositra, was found that this genus probably had a benthic juvenile stage that transitioned to a faculatively pseudoplanktonic adult.[60] |

| |

|

|

Shells |

A Pteriidaeoid wing-oyster. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A Clam, type member of the family Solemyidae inside Solemyida. |

| |

|

|

Shells |

A "posidoniid" ostreoidan. Another Genera mistaken with "Posidonia bronni". |

| |

|

|

Shells |

A mactromyid clam. |

Gastropoda

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Shells |

A Eucyclidae sea snail. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A coelodiscid sea snail. Is the oldest known holoplanktonic gastropod and the most abundant snail in the formation, thanks to a bilaterally symmetrical shell as an adaption to active swimming.[67] |

| |

|

|

Shells |

A Eucyclidae sea snail. |

| |

|

|

Shells |

| ||

|

|

Shells |

A Pleurotomariidae sea snail. |

| |

|

|

Shells |

A possible pterotracheid sea Slug. Dubious affinity.[68] |

| |

|

|

Shells |

A Procerithiidae sea snail. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A snail of uncertain placement. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A coelodiscid sea snail. Possible holoplanktonic gastropod.[67] |

||

|

|

Shells |

A zygopleurid sea snail. |

|

Cephalopoda

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Aptychi |

Ammonite internal moulds of uncertain affinity. |

||

|

|

Phragmocones |

|||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A diplobelid coleoid. Some specimens instead belong to Clarkeiteuthis (=Phragmoteuthis) conocauda. |

||

|

|

Pyritized fragments |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

A nautilid. Two referred specimens, identified as Nautilus spp. from Holzmaden were found encrusted with Serpulids and Bryozoans.[79] |

| |

|

|

Phragmocones |

A belemnotheutid belemnite. Chitinobelus rostrum was composed of aragonite with organic material, while normal belemnites had calcite. |

||

|

|

Phragmocones |

|||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

| ||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

Type genus of Coeloceratidae. |

||

|

|

Shells |

A dactylioceratid ammonite. It is common within the bituminous marls (incorrectly designated as "Wilder Schiefer"). |

||

|

|

Aptychi |

Ammonite internal moulds of uncertain affinity. |

| |

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

| ||

|

|

Phragmocones |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

A hildoceratid ammonite. The co-occurrence in Altdorf of boreal (Pseudolioceras) and Tethyan faunal elements (Frechiella) is striking, suggesting clear connection with both regions.[86] |

||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A geopeltid loligosepiid (Vampyromorpha). Related to the modern vampire squid. Gladius with weakly arcuated hyperbolar zones. |

| |

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A possible early Cuttlefish. It is one of the most important cephalopod fossils in the Sachrang Formation, due to having some of the earliest examples of pigments found on any species, also one of the first historically.[90] The pigments are preserved on various specimens with Eumelanin related to its ink sacs and including even phosphatized musculature.[10] |

||

|

|

Shells |

| ||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

Shells |

| |||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A loligosepiid loligosepiidan (Vampyromorpha). Related to the modern vampire squid. Gladii of Loligosepia can be distinguished from Jeletzkyteuthis by the transition lateral field/hyperbolar zone. |

||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Single specimen with tissue |

Type genus of Lioteuthididae inside Vampyromorphida. The taxonomic position of Lioteuthis is uncertain, although the fins reaching the proximal gladius section and the smooth median field suggest affinity to the Prototeuthididae[92] |

||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A loligosepiid loligosepiidan (Vampyromorpha).[94] The Loligosepiidae are believed to be ancestral to the modern vampire squid, Vampyroteuthis infernalis.[87] Hooklets in food residues in the posterior mantle indicate that Loligosepia preyed upon belemnites.[93] |

| |

|

|

Shells |

A lytoceratid ammonite. Lytoceras is relatively big, reaching nearly 50 cm in diameter. |

||

|

|

Shells |

| ||

|

|

Phragmocones |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A diplobelid coleoid. Has been confused with Acrocoelites tripartitus, hence the species name. |

||

|

|

Hooks |

Incertae sedis belemnites. |

||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A geopeltid loligosepiidan (Vampyromorpha). Related to the modern vampire squid. It is distinguished from Geoteuthis and Loligosepia by its median rib: this rib forms a narrow ridge between two narrow grooves. Probably bore fins similar to modern Vampyroteuthis.[11] |

||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Partial specimens with tissue |

A plesioteuthidid prototeuthidinan (Vampyromorpha). was originally described as "Geoteuthis" sagittata. |

||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

| ||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

A phylloceratid ammonite. The largest ammonite found in the Posidonienschiefer comes from the Ohmden quarry, and is a specimen of Phylloceras heterophyllum with a diameter of 87 cm.[71] |

| |

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Shells |

|||

|

|

Phragmocones |

| ||

|

|

MNHNL TI024, complete specimen |

|||

|

|

Phragmocones |

|||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A sueviteuthidid coleoid. Sueviteuthis had at least six arms with rather simple hooks, similar to the present of the genus Phragmoteuthis. |

||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

| ||

|

|

Shells |

| ||

|

|

Shell |

|||

|

|

Phragmocones |

A megateuthidid belemnite. Includes very large specimens |

| |

|

|

Shells |

Crustacea

[edit]Cycloidea

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Incomplete carapace |

The first cycloid arthropod from the Jurassic, from the family Halicynidae inside Cycloidea.[102] |

Ostracoda

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod of the family Bairdiidae inside Bairdioidea. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod of the family Bairdiidae inside Bairdioidea. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod of the family Cytherellidae inside Platycopida. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod of the family Cytherellidae inside Platycopida. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod of the family Cytheruridae inside Podocopida. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod of the family Healdiidae inside Podocopida. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod of the family Protostomia. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod of the family Protocytheridae inside Podocopida. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod, member of the family Pontocyprididae inside Podocopida. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod, member of the family Macrocyprididae inside Podocopida. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod of the family Bythocytheridae inside Cladocopina. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod, member of the family Healdiidae inside Podocopida. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod of the family Healdiidae inside Podocopida. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod of the family Polycopidae inside Cladocopina. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod of the family Praeschuleridea inside Podocopida. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod of the family Healdiidae inside Podocopida. |

||

|

|

Valves |

A marine ostracod, incertae sedis inside Podocopida. |

Malacostraca

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

An aegerid decapod. |

||

|

Single complete specimen in late larval stage |

The specimen reported represents the oldest fossil record of an achelate larva, and the first representative of achelates in the Posidonia Shale. This larva shares similarities with the late Jurassic genus Cancrinos. It is also among the oldest examples of crustaceans which possibly could have lived as part of the plankton.[109] |

| ||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A penaeid decapod. |

| |

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

An erymid decapod. |

||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

Type genus of the family Erymidae. Originally was placed within Glyphea as G. amalthei, informally used by Quenstedt and housed in the Museum Naturkunde in Württemberg. A series of later revisions proved it was a different genus.[113] |

| |

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A coleiid decapod. Was confussed with Proeryon hartmanni specimens. Specimens from Gomaringen are the first known with preserved ommatidia.[115] |

||

|

|

Isolated Chelae |

A decapod of the family Glypheidae. |

||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A decapod of the family Mecochiridae. |

||

|

|

Partial specimens. |

A penaeid decapod. |

||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

An erymid decapod. |

| |

|

|

Single specimen inside an ammonite shell. |

A hermit crab of the family Paguridae. This specimen was found inside an ammonite shell, probably looking to evade anoxic conditions or predators. |

||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A spiny lobster of the family Palinuridae |

||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A coleiid decapod. The second largest decapod from the formation, P. giganteus, reaches a larger size than most other polychelidans, growing up to 15 cm.[121] |

| |

|

|

Single Chela |

An erymid decapod. It was erroneously reported from the Late Toarcian. |

||

|

|

Single Incomplete specimen |

A possible mantis shrimp. |

| |

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

A gregarious polychelidan Lobster. specimens of Tonneleryon schweigerti were recovered generally in clusters of several individuals, due to that and the disposition of the specimens these probably represent mass-mortality assemblages and suggest this species was gregarious.[111] |

||

| Uncina[123] |

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens |

An astacidean decapod of the family Uncinidae. Uncina posidoniae is among the largest known Jurassic crustaceans andis also the largest representative of the genus.[123] |

|

Thoracica

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Numerous disarticulated individuals, associated with fossil wood.[15] |

A phosphatic-shelled barnacle of the family Eolepadidae.[15] Toarcolepas is provisionally interpreted as the oldest epiplanktonic barnacle known, and is thought to have lived attached to floating driftwood.[15] |

|

Arachnida

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Single incomplete specimen. |

The type genus of the family Liassoscorpionididae, probably related to Mesophonoidea.[125] |

|

Insecta

[edit]Incertae sedis

[edit]Insects are common terrestrial animals that were probably washed into the sea due to monsoon conditions present on the Sachrang Formation.[126]

| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Multiple specimens |

Incertae sedis |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens | |||

|

|

Multiple specimens | |||

|

|

Multiple specimens | |||

|

|

Multiple specimens | |||

|

|

Multiple specimens | |||

|

|

Multiple specimens | |||

|

|

Multiple specimens | |||

|

|

Multiple specimens | |||

|

|

Multiple specimens | |||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

Notoptera

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Multiple specimens |

Grylloblattidans of the family Geinitziidae. |

| |

|

|

Multiple specimens |

Eoblattida

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Multiple specimens |

An Eoblattidan of the family Blattogryllidae. |

Odonatoptera

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Multiple specimens |

An Odonatopteran (ancient winged insects) from the family Protomyrmeleontidae. |

Odonata

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campterophlebia[127][131] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Campterophlebiidae. The largest Early Jurassic insect known, with a wingspan up to 20 cm.[132] | |

| Elattogomphus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Liassogomphidae. | |

| Ensphingophlebia[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Sphenophlebiidae. | |

| Gallodorsettia[133] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Campterophlebiidae. | |

| Henrotayia[134] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Henrotayiidae. | |

| Heterothemis[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Heterophlebiidae. | |

| Heterophlebia[127][136] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Heterophlebiidae. | |

| Liassostenophlebia[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Mesoepiophlebia[137] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Sphenophlebiidae. | |

| Myopophlebia[127][137] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Myopophlebiidae. | |

| Necrogomphus[127][131] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Liassogomphidae. | |

| Paraheterophlebia[127][137] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Myopophlebiidae. | |

| Paraplagiophlebia[137] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Myopophlebiidae. | |

| Phthitogomphus[127][137] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Liassogomphidae. | |

| Plagiophlebia[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Heterophlebiidae. | |

| Proinogomphus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Liassogomphidae. | |

| Sphenophlebia[127][139] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Sphenophlebiidae.[140] | |

| Strongylogomphus[127][137] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A dragonfly of the family Myopophlebiidae. | |

| Syrrhoe[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis |

Orthoptera

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acridiopsis[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A short-horned grasshopper of the family Acrididae. |  |

| Chresmodella[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A stick insect of the family Aerophasmidae. | |

| Elcana[141] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A grasshopper of the family Elcanidae. | |

| Liadolocusta[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Grasshoppers of the family Locustopsidae. | |

| Liassogrylloides[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Locustopsis[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Grasshoppers of the family Locustopsidae. | |

| Panorpidium[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A grasshopper of the family Elcanidae. |  |

| Prophilaenites[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Protogryllus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A grasshopper of the family Protogryllidae. | |

| Schesslitziella[142][143] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A stick insect of the family Aerophasmidae. |

Dictyoptera

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blattula[127][144] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A cockroach of the family Blattulidae. | |

| Caloblattina[127][144] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A cockroach of the family Caloblattinidae. | |

| Liadoblattina[144] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A cockroach of the family Raphidiomimidae. | |

| Mesoblattina[144] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A cockroach of the family Mesoblattinidae. | |

| Ptyctoblattina[127][144] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A cockroach of the family Raphidiomimidae. |

Hemiptera

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archijassus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A Planthopper of the family Archijassidae. | |

| Compactofulgoridium[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Planthoppers of the family Fulgoridiidae. | |

| Corynecoris[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A shore bug (Saldidae) of the family Archegocimicidae. | |

| Deraiocoris[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A shore bug (Saldidae) of the family Archegocimicidae. | |

| Elasmoscelidium[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Ensphingocoris[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A shore bug (Saldidae) of the family Archegocimicidae. |  |

| Entomecoris[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | ||

| Eogerridium[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | ||

| Engynabis[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | ||

| Eurynotis[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | ||

| Fulgoridium[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Planthoppers of the family Fulgoridiidae. |  |

| Fulgoridulum[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Planthoppers of the family Fulgoridiidae. | |

| Indutionomarus[145] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A coleorrhynchan of the family Progonocimicidae. | |

| Macropterocoris[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A Shore bug (Saldidae) of the family Archegocimicidae. | |

| Margaroptilon[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Planthoppers of the family Fulgoridiidae. | |

| Megalocoris[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Saldidae Incertae sedis | |

| Metafulgoridium[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Planthoppers of the family Fulgoridiidae. | |

| Ophthalmocoris[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A shore bug (Saldidae) of the family Archegocimicidae. | |

| Procercopis[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A froghopper of the family Procercopidae. | |

| Procerofulgoridium[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Planthoppers of the family Fulgoridiidae. | |

| Productofulgoridium[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Planthoppers of the family Fulgoridiidae. | |

| Pronabis[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A shore bug (Saldidae) of the family Archegocimicidae. | |

| Somatocoris[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A shore bug (Saldidae) of the family Archegocimicidae. | |

| Tetrafulgoria[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Planthoppers of the family Fulgoridiidae. | |

| Xulsigia[146] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A sternorrhynchan of the family Pincombeomorpha. Has been proposed to be within its own family, Xulsigiidae. |

Hymenoptera

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liadobracona[147] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A wasp of the family Ephialtitidae. | |

| Pseudoxyelocerus[148] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A wood wasp of the family Xyelotomidae. |

|

| Symphytopterus[149] |

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A wasp of the family Ephialtitidae. |

|

| Thilopterus[150] |

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A wasp of the family Ephialtitidae. |

|

| Xyelula[150] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A cephoidean of the family Sepulcidae. |

|

Neuroptera

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinophlebia[151] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A lacewing of the family Prohemerobiidae. | |

| Actinoptilon[151] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A silky lacewing of the family Psychopsidae. |  |

| Epipanfilovia[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A lacewing of the family Panfiloviidae. | |

| Glottopteryx[127][151] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A lacewing of uncertain placement. | |

| Liassopsychops[127][152] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A giant lacewing of the family Kalligrammatidae. It is one of the oldest known representatives of the giant pollinator lacewings.[153] | |

| Mesosmylina[151] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Lance lacewings of the family Osmylidae. |  |

| Mesopsychopsis[151] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A lance lacewing of the family Osmylopsychopidae. | |

| Ophtalmogramma[152] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A giant lacewing of the family Kalligrammatidae. | |

| Panfilovia[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A lacewing of the family Panfiloviidae. A large genus with wings around 50 mm. | |

| Paractinophlebia[151] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A lacewing of the family Prohemerobiidae. | |

| Parhemerobius[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A lacewing of the family Prohemerobiidae. | |

| Prohemerobius[127][151] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A lacewing of the family Prohemerobiidae. | |

| Protoaristenymphes[154] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A lance lacewing of the family Mesochrysopidae. | |

| Stenoteleuta[151] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A lacewing of the family Prohemerobiidae. | |

| Tetanoptilon[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Lance lacewings of the family Osmylidae. Tetanoptilon is the largest non-kalligrammatid lacewing of the Jurassic.[153] |

Hemiptera

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adelocoris[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Pentatomomorphans of the family Pachymeridiidae. Related with the group Lygaeoidea, possibly being ancestral to them. |  |

| Engerrophorus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | ||

| Euraspidium[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | ||

| Ischnocoris[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | ||

| Liassocicada[127][142][155] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A Hairy Cicada of the family Tettigarctidae. |  |

| Liassotettigarcta[142] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | ||

| Mesomphalocoris[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Pentatomomorphans of the family Pachymeridiidae. | |

| Stiphroschema[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Pentatomomorphans of the family Pachymeridiidae. | |

| Trachycoris[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Pentatomomorphans of the family Pachymeridiidae. |

Coleoptera

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amblycephalonius[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Beetles of the family Coptoclavidae. | |

| Amphoxyne[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Aposphinctus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A water scavenger beetle of the family Hydrophilidae. |  |

| Apicasia[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Apiopyrenides[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Aptilotitus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Auchenophorites[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Brachylaimon[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Brachytrachelites[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Camaricopterus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A beetle of the family Phoroschizidae. | |

| Coreoeicos[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | False ground beetles of the family Trachypachidae. | |

| Diatrypamene[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Dicyphelus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Diphymation[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Diplocelides[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Diplothece[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Entomocantharus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Episcepes[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Eurynotellus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Eurysphinctus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Eusarcantarus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Grasselites[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Gastrodelus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Gastroratus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Hydroicetes[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Laimocenos[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Leptomites[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Leptosolenophorus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Loxocamarotus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Macrotrachelites[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Megachorites[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Melanocantharis[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Metanastes[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Mesoncus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Mesotylites[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Omogongylus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Ooidellus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Ooperiglyptus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Ooperioristus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Beetles of the family Coptoclavidae. | |

| Opiselleipon[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Oxycephalites[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Palaeotrachys[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Parnosoma[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Peridosoma[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Pholipheron[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Proheuristes[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Prosynactus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | False ground beetles of the family Trachypachidae. |  |

| Pleuralocista[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Rhomaleus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Rhysopsalis[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Sphaericites[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Tetragonides[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Trichelepturgetes[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Trochmalus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Scalopoides[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Sideriosemion[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Sphaerocantharis[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Syntomopterus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Tripsalis[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Trochiscites[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Tolype[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Zetemenos[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis |

Amphiesmenoptera

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necrotaulius[142][127][126][156] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | An Amphiesmenopteran of the family Necrotauliidae. The ovipositor terminalia of female N. parvulus indicate that these insects laid their eggs in soil rather than in water. | |

| Micropterygidae[156] | Indeterminate |

|

Multiple specimens | Lepidopterans probably related with the family Micropterygidae. Compared with their record in Grimmen, in Lower Saxony lepidopterans are rather scarce and badly preserved. |  |

Miscellaneous (incl. Diptera)

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amblylexis[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Amianta[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Amphipromeca[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Apistogrypotes[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Archipleciomima[157] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Architipula[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A crane fly of the family Limoniidae. |  |

| Bodephora[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Culiciscolex[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Cyrtomides[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Ellipibodus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Eoptychoptera[142][158] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A phantom crane fly of the family Eoptychopterinae. | |

| Empidocampe[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Geisfeldiella[159] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Mayfly of the family Protereismatidae. | |

| Haplobittacus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A hangingfly of the family Bittacidae. | |

| Haplotipula[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A crane fly of the family Limoniidae. | |

| Heterorhyphus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A fly of the family Heterorhyphidae. | |

| Homoeoptychopteris[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Hondelagia[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A snakefly of the family Priscaenigmatidae. | |

| Liassonympha[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Leptotipuloides[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A crane fly of the family Limoniidae. | |

| Mikrotipula[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A crane fly of the family Limoniidae. | |

| Mesobittacus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A hangingfly of the family Bittacidae. | |

| Mesopanorpa[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A scorpionfly of the family Orthophlebiidae. | |

| Metaraphidia[147] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A snakefly of the family Metaraphidiidae. | |

| Mesorhyphus[157] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A wood gnat of the family Anisopodidae. |  |

| Metatrichopteridium[160] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A fly of the family Hennigmatidae. It represents the oldest known genus of this primitive family. | |

| Nannotanyderus[142][161] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A primitive crane fly of the family Tanyderidae. Extant members of the family are nectar feeder while the diets of extinct members cannot be determined precisely.[162] |  |

| Neorthophlebia[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A hangingfly of the family Bittacidae. | |

| Orthophlebia[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A scorpionfly of the family Orthophlebiidae. | |

| Ozotipula[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A crane fly of the family Limoniidae. | |

| Parabittacus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A hangingfly of the family Bittacidae. | |

| Parorthophlebia[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Scorpionflies of the family Orthophlebiidae. | |

| Pleobittacus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A hangingfly of the family Bittacidae. | |

| Praemacrochile[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A primitive crane fly of the family Tanyderidae. | |

| Propexis[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Protobittacus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A hangingfly of the family Bittacidae. |  |

| Protorthophlebia[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Scorpionflies of the family Protorthophlebiidae. | |

| Protoplecia[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A fly of the family Protopleciidae. | |

| Protorhyphus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | A fly of the family Protorhyphidae. | |

| Pseudopolycentropus[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Scorpionflies of the family Pseudopolycentropodidae. | |

| Reprehensa[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Scorpionflies of the family Orthophlebiidae. | |

| Rhopaloscolex[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis | |

| Sphallonymphites[127] |

|

|

Multiple specimens | Incertae sedis |

Echinodermata

[edit]Echinoderm debris is relatively abundant in the shale-free Unken and Salzburg members, including crinoid and brittle star skeletal elements; sea urchins take their place later in the formation, with them having especially diversified at that time, leading to pedicellaria being observed very often.[40]

Asterozoa

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star within the family Ophiomusina. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in incertae sedis family in the order Ophionereididae. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in the family Ophiolepididae. |

| |

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in incertae sedis family in the order Ophiodermatina. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in the family Euryophiurida. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in the family Ophioscolecidae. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star un the family Ophiacanthida. Very common, related to non anoxic water sedimentation. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in the family Ophiomusaidae. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in the family Ophiotomidae. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

An Ophiuridan in the family Ophiuridae. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in the family Ophiohelidae. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in the family Ophiomusaidae. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in the family Astrophiuridae. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in the family Ophiactidae. Very rare in the layers. |

| |

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in the family Ophiopyrgidae. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in the family Ophiopyrgidae. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in the family Ophioleucidae. The dominant asterozoan taxon in the formation. |

| |

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A brittle star in the family Ophiomusina. |

Echinoidea

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A sea urchin in the family Cidaridae. |

| |

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A sea urchin in the family Pedinidae. It is the most common sea urchin found in the formation |

| |

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A sea urchin in the family Diadematidae |

| |

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A sea urchin in the family Pedinidae |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A sea urchin in the family Miocidaridae |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A sea urchin in the family Pseudodiadematidae |

Holothuroidea

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A sea cucumber in the family Achistridae inside Apodida. |

| |

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A sea cucumber in the family Calclamnidae inside Dendrochirotida. |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A sea cucumber in the family Stichopitidae. Occurs sporadically in non-bituminous sediments in the upper bifrons zone |

||

|

|

Multiple specimens |

A sea cucumber in the family Chiridotidae. It is the only major genus of sea cucumber reported locally in the Posidonienschiefer. |

Crinoidea

[edit]| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens, some associated with rafts. |

Type genus of the family Pentacrinitidae. Like Seirocrinus, Pentacrinites formed colonies in rafting wood. Was a small genus, with multiple specimens no more than 1 meter long, usually measuring 40–70 cm. |

| |

|

|

Isolated Stems |

A crinoid in the family Plicatocrinidae. |

||

|

|

Exceptionally well preserved individual with the arms, pinnules and cirri largely intact |

A crinoid in the family Isocrinida. This benthic crinoid clearly represents an exotic element in the typical Posidonia fauna, likely moved from coastal settings. |

||

|

|

Various complete and nearly complete specimens, some associated with rafts |