Ozzy Osbourne

Ozzy Osbourne | |

|---|---|

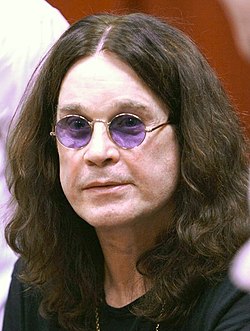

Osbourne in 2010 | |

| Born | John Michael Osbourne 3 December 1948 Marston Green, Warwickshire, England |

| Died | 22 July 2025 (aged 76) Jordans, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Resting place | Welders House, Jordans, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Other names |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Spouses | |

| Children | 6, including Aimee, Kelly and Jack |

| Musical career | |

| Origin | Aston, Birmingham, England |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1967–2025 |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | Black Sabbath |

| Website | ozzy |

| Signature | |

| |

John Michael "Ozzy" Osbourne (3 December 1948 – 22 July 2025) was an English singer, songwriter, and media personality. He co-founded the pioneering heavy metal band Black Sabbath in 1968, and rose to prominence in the 1970s as their lead vocalist. During this time, he adopted the title "Prince of Darkness".[3][4] He performed on the band's first eight albums, most notably including Black Sabbath, Paranoid (both 1970) and Master of Reality (1971), before he was fired in 1979 due to his problems with alcohol and other drugs.

Osbourne began a solo career in the 1980s and formed his band with Randy Rhoads and Bob Daisley, with whom he recorded the albums Blizzard of Ozz (1980) and Diary of a Madman (1981). Throughout the decade, he drew controversy for his antics both onstage and offstage, and was accused of promoting Satanism by the Christian right. Overall, Osbourne released thirteen solo studio albums, the first seven of which were certified multi-platinum in the United States. He reunited with Black Sabbath on several occasions. He rejoined from 1997 to 2005, and again in 2012; during this second reunion he sang on the band's last studio album, 13 (2013), before they embarked on a farewell tour that ended in 2017. On 5 July 2025, Osbourne performed his final show at the Back to the Beginning concert in Birmingham, having announced that it would be his last due to health issues. Although he intended to continue recording music, he died 17 days later, on 22 July.

Osbourne sold more than 100 million albums, including his solo work and Black Sabbath releases.[5][6] He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of Black Sabbath in 2006[7] and as a solo artist in 2024.[8] He was also inducted into the UK Music Hall of Fame both solo and with Black Sabbath in 2005. He was honoured with stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame[9] on 12 April 2002 and Birmingham Walk of Stars on 6 July 2007. At the 2014 MTV Europe Music Awards, he received the Global Icon Award. In 2015, he received the Ivor Novello Award for Lifetime Achievement from the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors.

Osbourne's wife and manager Sharon founded the heavy metal touring festival Ozzfest, which was held yearly from 1996 to 2010. In the early 2000s, he became a reality television star when he appeared in the MTV reality show The Osbournes (2002–2005) alongside Sharon and two of their children, Kelly and Jack. He co-starred with some of his family in the television series Ozzy & Jack's World Detour (2016–2018) as well as The Osbournes Want to Believe (2020–2021).

Early life

John Michael Osbourne was born at the maternity hospital in Marston Green (then in Warwickshire) on 3 December 1948,[10] and grew up in the Aston area of Birmingham.[11][12] His mother, Lilian (née Unitt; 1916–2001), was a non-observant Catholic who worked at a Lucas factory.[13][14][15] His father, John Thomas "Jack" Osbourne (1915–1977), worked night shifts as a toolmaker at the General Electric Company.[16][17] Osbourne had three older sisters named Jean, Iris and Gillian, and two younger brothers named Paul and Tony.[18] The family lived in a small two-bedroom home at 14 Lodge Road in Aston. Osbourne gained the nickname "Ozzy" as a child.[19] He dealt with dyslexia at school.[20] His accent was described as "hesitant Brummie".[21]

At the age of 11, Osbourne suffered sexual abuse from school bullies.[22] He said he attempted suicide multiple times as a teenager.[23][24] He participated in school plays, including Gilbert and Sullivan's The Mikado and H.M.S. Pinafore.[25] Upon hearing the first hit single of the Beatles at age 14, he became a fan of the band and credited their 1963 song "She Loves You" with inspiring him to become a musician.[17][26] In the 2011 documentary God Bless Ozzy Osbourne, Osbourne said that the Beatles made him realise that "[he] was going to be a rock star the rest of [his] life".[27]

Osbourne left school at the age of 15 and was employed as a construction site labourer, trainee plumber, apprentice toolmaker, car factory horn-tuner and slaughterhouse worker. At the age of 17, he was convicted of robbing a clothes shop, but was unable to pay the fine; his father also refused to pay it to teach him a lesson, resulting in Osbourne spending six weeks in Winson Green Prison.[16][28]

Musical career

Black Sabbath

In late 1967, Geezer Butler formed his first band, Rare Breed, and recruited Osbourne to be the singer.[19] The band played two shows and broke up. Osbourne and Butler reunited in another band, Polka Tulk Blues, which included guitarist Tony Iommi and drummer Bill Ward, whose band Mythology had recently broken up. They renamed the band Earth, but after being accidentally booked for a show instead of a different band with the same name, they decided to change the band's name again, settling on the name Black Sabbath in August 1969. The band's name was inspired by the film of the same title.[29] Black Sabbath noticed how people enjoyed being frightened during their appearances, which inspired their decision to play a heavy blues style of music laced with gloomy sounds and lyrics.[11] While recording their first album, Butler read an occult book and woke up seeing a dark figure at the end of his bed. Butler told Osbourne about it, and together they wrote the lyrics to "Black Sabbath", their first song in a darker vein.[30][31]

The band's US record label, Warner Bros. Records, invested only modestly in it, but Black Sabbath achieved swift and enduring success. Built around Tony Iommi's guitar riffs, Geezer Butler's lyrics, Bill Ward's dark tempo drumbeats, and topped by Osbourne's eerie vocals, their debut album, Black Sabbath, and second, Paranoid, were commercially successful and also gained considerable radio airplay. Osbourne recalled, however, that, "in those days, the band wasn't very popular with the women".[19] At about this time, Osbourne first met his future wife, Sharon Arden.[19] After the unexpected success of their first album, Black Sabbath were considering her father, Don Arden, as their new manager, and Sharon was at that time working as Don's receptionist.[19] Osbourne admitted he was attracted to her immediately but assumed that "she probably thought I was a lunatic".[19] Osbourne later recalled that the best thing about eventually choosing Don Arden as manager was that he got to see Sharon regularly, though their relationship was strictly professional at that point.[19]

Just five months after the release of Paranoid, the band released Master of Reality. The album reached the top ten in both the United States and UK, and was certified gold in less than two months.[32] In the 1980s, it received platinum certification[32] and went Double Platinum in the early 21st century.[32] Reviews of the album were unfavourable. Lester Bangs of Rolling Stone famously dismissed Master of Reality as "naïve, simplistic, repetitive, absolute doggerel", although the very same magazine would later place the album at number 298 on their 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list, compiled in 2003.[33]

In September 1972, Black Sabbath released Black Sabbath Vol. 4. Critics were dismissive of the album; however, it reached gold status in less than a month and was the band's fourth consecutive album to sell more than one million copies in the United States.[31][34][35] In November 1973, Black Sabbath released the critically acclaimed Sabbath Bloody Sabbath. For the first time, the band received favourable reviews in the mainstream press. Gordon Fletcher of Rolling Stone called the album "an extraordinarily gripping affair" and "nothing less than a complete success".[36] Decades later, AllMusic's Eduardo Rivadavia called the album a "masterpiece, essential to any heavy metal collection", while also claiming the band displayed "a newfound sense of finesse and maturity".[37] The album marked the band's fifth consecutive platinum selling album in the United States.[38] Sabotage was released in July 1975. Again, there were favourable reviews. Rolling Stone stated, "Sabotage is not only Black Sabbath's best record since Paranoid, it might be their best ever."[39] In a retrospective review, AllMusic was less favourable, noting that "the magical chemistry that made such albums as Paranoid and Volume 4 so special was beginning to disintegrate".[40] Technical Ecstasy, released on 25 September 1976, was also met with mixed reviews. AllMusic gives the album two stars, and notes that the band was "unravelling at an alarming rate".[41]

Dismissal

Between late 1977 and early 1978,[42] Osbourne left the band for three months to pursue a solo project called Blizzard of Ozz,[43] a title which had been suggested by his father.[44] Three members of the band Necromandus, who had supported Sabbath in Birmingham when they were called Earth, backed Osbourne in the studio and briefly became the first incarnation of his solo band.[45]

At the request of the other band members, Osbourne rejoined Sabbath.[46] The band spent five months at Sounds Interchange Studios in Toronto, where they wrote and recorded their next album, Never Say Die! "It took quite a long time", Iommi said of Never Say Die! "We were getting really drugged out, doing a lot of dope. We'd go down to the sessions, and have to pack up because we were too stoned; we'd have to stop. Nobody could get anything right; we were all over the place, and everybody was playing a different thing. We'd go back and sleep it off, and try again the next day."[47]

In May 1978, Black Sabbath began the Never Say Die! Tour with Van Halen as an opening act. Reviewers called Sabbath's performance "tired and uninspired" in stark contrast to the "youthful" performance of Van Halen, who were touring the world for the first time.[48] The band recorded their concert at Hammersmith Odeon in June 1978, which was released on video as Never Say Die. The final show of the tour and Osbourne's last appearance with Black Sabbath for another seven years, until 1985, was in Albuquerque, New Mexico on 11 December.[49]

In 1979, Black Sabbath returned to the studio, but tension and conflict arose between band members. Osbourne recalled being asked to record his vocals over and over, and tracks were manipulated endlessly by Iommi.[50] The relationship between Osbourne and Iommi became contentious. On 27 April 1979, at Iommi's insistence but with the support of Butler and Ward, Osbourne was ejected from Black Sabbath.[19] The reasons provided to him were that he was unreliable and had excessive substance abuse issues compared to the other members. Osbourne maintained that his use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs at that time was similar to that of the other members.[51]

The band replaced Osbourne with former Rainbow singer Ronnie James Dio.[31] In a 21 August 1987 interview with Tommy Vance on BBC Radio 1's Friday Rock Show, Dio said, "I was not, and never will be, Ozzy Osbourne. He was the vocalist and songwriter in that era who helped create that band and make it what it was, and what it is in its classic form."[52]

The conflict between Iommi and Osbourne commenced almost immediately in their working collaboration. Responding to a flyer that read, "Ozzy Zig Needs Gig- has own PA",[53] which was posted by Osbourne in a record store, Iommi and Ward arrived at the listed address to speak with Ozzy Zig, as he then called himself. When Iommi saw Osbourne emerge from another room of the house, he recalled that he knew him as a "pest" from their school days.[19] Iommi recalls one incident in the early 1970s in which Osbourne and Butler were fighting in a hotel room. Iommi pulled Osbourne off Butler in an attempt to break up the drunken fight, and the vocalist proceeded to turn around and take a wild swing at him. Iommi responded by knocking Osbourne unconscious with one punch to the jaw.[54]

Black Sabbath reunions

Following two brief, short-set reunions for Live Aid in 1985 and at an Ozzy Osbourne show in Costa Mesa, California, on 15 November 1992, Osbourne, Iommi and Butler formally reunited as Black Sabbath in 1997 for the 1997 Ozzfest shows.[55] Ward was absent due to health issues.[55] In December 1997, all four members of the band reunited to record the album Reunion, with Osbourne also touring with the band again from 1997 to 1999 for the album's concert tour.[31][56][57][58] The album proved to be a commercial success upon its release in October 1998.[57]

The original Black Sabbath line-up of Ozzy, Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler, and Bill Ward reunited in November 2011 for a world tour and new album.[59] Ward had to drop out for contractual reasons, so the project continued with Rage Against the Machine's Brad Wilk stepping in for Ward on drums. They played their first reunion concert in May 2012, at the O2 Academy in their hometown Birmingham.[60] The album, entitled 13, was released on 11 June 2013,[61] and topped both the UK Albums Chart and the US Billboard 200.[62][63]

In January 2016, the band began a farewell tour, titled "The End", supposedly signifying the final performances of Black Sabbath.[64][65] The final shows of The End tour took place at the Genting Arena in their home city of Birmingham on 2 and 4 February 2017, with Tommy Clufetos replacing Bill Ward as the drummer for the final show.[66][67]

On 8 August 2022, Osbourne and Iommi made a surprise appearance during the closing ceremony of the 2022 Commonwealth Games in Birmingham. This marked Osbourne's first live performance in three years, following a period of ill health.[68][69]

Osbourne played his final show, billed as "Back to the Beginning", alongside the original line-up of Black Sabbath, at Villa Park in Birmingham on 5 July 2025.[70] The band and Osbourne each played a short set, watched by a crowd of more than 40,000 spectators and a peak livestream audience of 5.8 million. Having been rendered unable to stand from Parkinson's disease, Osbourne performed seated on a black throne.[71] All proceeds from the event will be donated equally to The Cure Parkinson's Trust, Birmingham Children's Hospital, and Acorn Children's Hospice.[72]

Solo career

Signing to Jet records

After leaving Black Sabbath, Osbourne recalled, "I'd got £96,000 for my share of the name, so I'd just locked myself away and spent three months doing coke and booze. My thinking was, 'This is my last party, because after this I'm going back to Birmingham and the dole."[73] However, Don Arden signed him to Jet Records with the aim of recording new material. Arden dispatched his daughter Sharon to Los Angeles to "look after Ozzy's needs, whatever they were", to protect his investment.[74] Arden initially hoped Osbourne would return to Sabbath, who he was personally managing at that time, and later attempted to convince the singer to name his new band "Son of Sabbath", which Osbourne hated.[19] Sharon attempted to convince Osbourne to form a supergroup with guitarist Gary Moore.[19] "When I lived in Los Angeles", Moore recalled, "[Moore's band] G-Force helped him to audition musicians. If drummers were trying out, I played guitar, and if a bassist came along, my drummer would help out. We felt sorry for him, basically. He was always hovering around trying to get me to join, and I wasn't having any of it."[75]

Blizzard of Ozz

In late 1979, under the management of the Ardens, Osbourne formed the Blizzard of Ozz,[76] featuring bassist-lyricist Bob Daisley (of Rainbow and, later, Uriah Heep), guitarist Randy Rhoads (of Quiet Riot), drummer Lee Kerslake (of Uriah Heep), and keyboardist Don Airey (of Rainbow and, later, Deep Purple) as a session musician. The record company eventually titled the group's debut album Blizzard of Ozz, credited simply to Osbourne, thus commencing his solo career. Co-written with Daisley and Rhoads, it brought Osbourne considerable success on his first solo effort. Though it is generally accepted that Osbourne and Rhoads started the band, Daisley later claimed that he and Osbourne formed the band in England before Rhoads officially joined.[77]

Blizzard of Ozz is one of the few albums among the 100 best-sellers of the 1980s to have achieved multi-platinum status without the benefit of a top-40 single. As of August 1997, it had achieved quadruple platinum status, according to RIAA.[78] "I envied Ozzy's career..." remarked former Sabbath drummer Bill Ward. "He seemed to be coming around from whatever it was that he'd gone through, and he seemed to be on his way again; making records and stuff... I envied it because I wanted that... I was bitter. And I had a thoroughly miserable time."[79]

Diary of a Madman

Osbourne's second album, Diary of a Madman, featured more songs co-written with Lee Kerslake. For his work on this album and Blizzard of Ozz, Rhoads[29] was ranked the 85th-greatest guitarist of all time by Rolling Stone magazine in 2003.[80] This album is known for the singles "Over the Mountain" and "Flying High Again" and, as Osbourne explained in his autobiography, was his personal favourite.[19] Tommy Aldridge and Rudy Sarzo soon replaced Kerslake and Daisley. Aldridge had been Osbourne's original choice for drummer, but a commitment to Gary Moore had made him unavailable.[74]

On 19 March 1982, the band was in Florida for its Diary of a Madman tour, a week away from playing Madison Square Garden in New York City. A light aircraft piloted by Andrew Aycock, the band's tour bus driver, carrying Rhoads and Rachel Youngblood, the band's costume and make-up designer, crashed while performing low passes over the band's tour bus. The left wing of the aircraft clipped the bus, causing the plane to graze a tree and crash into the garage of a nearby mansion, killing Rhoads, Aycock, and Youngblood. The crash was ruled the result of "poor judgement by the pilot in buzzing the bus and misjudging clearance of obstacles".[81] Experiencing first-hand the horrific death of his close friend and bandmate, Osbourne fell into a deep depression. The tour was cancelled for two weeks while Osbourne, Sharon, and Aldridge returned to Los Angeles to take stock while Sarzo remained in Florida with family.[82]

Gary Moore was the first to be approached to replace Rhoads, but refused.[82] With a two-week deadline to find a new guitarist and resume the tour, Robert Sarzo, brother of the band's bassist Rudy Sarzo, was chosen to replace Rhoads. Former Gillan guitarist Bernie Tormé, however, flew to California from England with the promise from Jet Records that he had the job. Once Sharon realised that Jet Records had already paid Tormé an advance, he was reluctantly hired instead of Sarzo. The tour resumed on 1 April 1982, but Tormé's blues-based style was unpopular with fans. After a handful of shows he informed Sharon that he would be returning to England to continue work on a solo album he had begun before coming to the United States.[83] At an audition in a hotel room, Osbourne selected Night Ranger's Brad Gillis to finish the tour. The tour culminated in the release of the 1982 live album Speak of the Devil, recorded at The Ritz in New York City.[84][85] A live tribute album for Rhoads was also later released. Despite the difficulties, Osbourne moved on after Rhoads's death. Speak of the Devil, known in the United Kingdom as Talk of the Devil, was originally planned to consist of live recordings from 1981, primarily from Osbourne's solo work. Under contract to produce a live album, it ended up consisting entirely of Sabbath covers recorded with Gillis, Sarzo and Tommy Aldridge.[86]

In 1982, Osbourne appeared as lead vocalist on the Was (Not Was) pop dance track "Shake Your Head (Let's Go to Bed)". Remixed and rereleased in the early 1990s for a Was (Not Was) hits album in Europe, it reached number four on the UK Singles Chart.[87] In 1983, Jake E. Lee, formerly of Ratt and Rough Cutt, joined Osbourne to record Bark at the Moon. The album, cowritten with Daisley, featured Aldridge and former Rainbow keyboard player Don Airey. The album's title track, whose video was partially filmed at Holloway Sanitorium outside London, became a fan favourite. Within weeks the album became certified gold. It has sold three million copies in the United States.[88] 1986's The Ultimate Sin followed (with bassist Phil Soussan[89] and drummer Randy Castillo), and touring behind both albums with former Uriah Heep keyboardist John Sinclair joining prior to the Ultimate Sin tour. At the time of its release, The Ultimate Sin was Osbourne's highest-charting studio album. The RIAA awarded the album Platinum status on 14 May 1986, soon after its release; it was awarded Double Platinum status on 26 October 1994.[90]

Jake E. Lee and Osbourne parted ways in 1987. Osbourne continued to struggle with chemical dependency. That year, he commemorated the fifth anniversary of Rhoads's death with Tribute, a collection of live recordings from 1981. In 1988, Osbourne appeared in The Decline of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal Years and told the director Penelope Spheeris that "sobriety fucking sucks". Meanwhile, Osbourne found Zakk Wylde, who was the most enduring replacement for Rhoads to date.[91] Together, they recorded No Rest for the Wicked with Castillo on drums, Sinclair on keyboards, and Daisley co-writing lyrics and playing bass. The subsequent tour saw Osbourne reunited with erstwhile Black Sabbath bandmate Geezer Butler on bass. A live EP (entitled Just Say Ozzy) featuring Geezer was released two years later. In 1988, Osbourne performed on the rock ballad "Close My Eyes Forever", a duet with Lita Ford, reaching No. 8 on the Billboard Hot 100.[92] In 1989, Osbourne performed at the Moscow Music Peace Festival.[93]

No More Tears and Ozzmosis

Osbourne's commercial success of the 1980s continued with 1991's No More Tears, featuring "Mama, I'm Coming Home". The album enjoyed much radio and MTV exposure. It also initiated a practice of bringing in outsiders (in this case Lemmy Kilmister of Motorhead) to help write Osbourne's material, instead of relying on his recording ensemble. The album was mixed by veteran rock producer Michael Wagener. Osbourne was awarded a 1994 Grammy for the track "I Don't Want to Change the World" from Live & Loud, for Best Metal Performance.[94] Wagener also mixed the live album Live & Loud released on 28 June 1993. Intended to be Osbourne's final album, it went platinum four times over,[95] and had a peak ranking of number 22 on the Billboard 200 chart.[96]. In 1992, Osbourne expressed his fatigue with touring, and proclaimed his "retirement tour" (the retirement was to be short-lived), called "No More Tours", a pun on No More Tears.[97] Alice in Chains's Mike Inez took over on bass and Kevin Jones played keyboards as Sinclair was touring with the Cult.[98]

Osbourne's entire CD catalogue was remastered and reissued in 1995. The same year, Osbourne released Ozzmosis and resumed touring, dubbing his concert performances "The Retirement Sucks Tour". The album reached number 4 on the US Billboard 200. The RIAA certified the album gold and platinum in that same year, and double platinum in April 1999.[99]

The line-up on Ozzmosis was Wylde, Butler (who had just quit Black Sabbath again), Steve Vai, and Hardline drummer Deen Castronovo, who later joined Journey. Keyboards were played by Rick Wakeman and producer Michael Beinhorn.[100] The tour maintained Butler and Castronovo and saw Sinclair return, but a major line-up change was the introduction of former David Lee Roth guitarist Joe Holmes. Wylde was considering an offer to join Guns N' Roses. Unable to wait for a decision on Wylde's departure, Osbourne replaced him.[101] In early 1996, Butler and Castronovo left. Inez and Randy Castillo (Lita Ford, Mötley Crüe) filled in.[102] Ultimately, Faith No More's Mike Bordin and former Suicidal Tendencies and future Metallica bassist Robert Trujillo joined on drums and bass respectively. A greatest hits package, The Ozzman Cometh, was issued in 1997.[103]

Down to Earth

Down to Earth, Osbourne's first album of new studio material in six years, was released on 16 October 2001. A live album, Live at Budokan, followed in 2002. Down to Earth, which achieved platinum status in 2003, featured the single "Dreamer", a song which peaked at number 10 on Billboard's Mainstream Rock Tracks.[104] In June 2002, Osbourne was invited to participate in the Golden Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II, performing the Black Sabbath anthem "Paranoid" at the Party at the Palace concert in the grounds of Buckingham Palace.[105] In 2003, Osbourne recruited former Metallica bassist Jason Newsted, though his time with Osbourne would be short. Osbourne's former bassist Robert Trujillo replaced Newsted in Metallica during this same period.[106]

On 8 December 2003, Osbourne was rushed into emergency surgery at Slough's Wexham Park Hospital following an accident with his quad bike on his estate in Jordans, Buckinghamshire.[107] Osbourne broke his collar bone, eight ribs, and a neck vertebra.[107] An operation was performed to lift the collarbone, which was believed to be resting on a major artery and interrupting blood flow to one of Osbourne's arms. Sharon later revealed that Osbourne had stopped breathing following the crash and was resuscitated by Osbourne's then personal bodyguard, Sam Ruston. While in hospital, Osbourne achieved his first ever UK number one single, a duet of the Black Sabbath ballad, "Changes" with daughter Kelly.[108] In doing so, he broke the record of the longest period between an artist's first UK chart appearance (with Black Sabbath's "Paranoid", number four in August 1970) and their first number one hit: a gap of 33 years.[108] He recovered from the quad accident and went on to headline the 2004 Ozzfest, with the reunited Black Sabbath.[109]

Box set release and Black Rain

In March 2005, Osbourne released a box set called Prince of Darkness. The first and second discs are collections of live performances, B-sides, demos and singles. The third disc contained duets and other odd tracks with other artists, including "Born to Be Wild" with Miss Piggy. The fourth disc, is entirely new material where Osbourne covers his favourite songs by his biggest influences and favourite bands, including the Beatles, John Lennon, David Bowie and others.[110] In November 2005, Osbourne released the covers album Under Cover, featuring 10 songs from the fourth disc of Prince of Darkness and 3 more songs.[111] Osbourne's band for this album included Alice in Chains guitarist Jerry Cantrell,[112] bassist Chris Wyse[112] and Faith No More drummer Mike Bordin.[112]

Osbourne also helped judge the 2005 UK series of the X-Factor where his wife Sharon was one of the main judges.[113] In March 2006, he said that he hoped to release a new studio album soon with longtime on-off guitarist, Zakk Wylde of Black Label Society.[114] In October 2006, it was announced that Tony Iommi, Ronnie James Dio, Bill Ward, and Geezer Butler would be touring together again, though not as Black Sabbath but under the moniker "Heaven & Hell", the title of Dio's first Black Sabbath album.[115]

Osbourne's next album, titled Black Rain, was released on 22 May 2007. His first new studio album in almost six years, it featured a more serious tone than previous albums. "I thought I'd never write again without any stimulation... But you know what? Instead of picking up the bottle I just got honest and said, 'I don't want life to go [to pieces]'", Osbourne stated to Billboard magazine.[116]

Band changes and Scream

Osbourne revealed in July 2009 that he was currently seeking a new guitar player. While he stated that he had not fallen out with Zakk Wylde, he said he felt his songs were beginning to sound like Black Label Society and fancied a change.[117] In August 2009, Osbourne performed at the gaming festival BlizzCon with a new guitarist in his line-up, Gus G.[118] Osbourne also provided his voice and likeness to the video game Brütal Legend character The Guardian of Metal.[119] In November, Slash featured Osbourne on vocals in his single "Crucify the Dead",[120] and Osbourne with wife Sharon were guest hosts on WWE Raw.[121] In December, Osbourne announced he would be releasing a new album titled Soul Sucka with Gus G, Tommy Clufetos on drums, and Blasko on bass.[122] Negative fan feedback was brought to Osbourne's attention regarding the album title. In respect of fan opinion, on 29 March Osbourne announced his album would be renamed Scream.[123]

On 13 April 2010, Osbourne announced the release date for Scream would be 15 June 2010.[124] The release date was later changed to a week later. A single from the album, "Let Me Hear You Scream", debuted on 14 April 2010 episode of CSI: NY.[125]

On 9 August 2010, Osbourne announced that the second single from the album would be "Life Won't Wait" and the video for the song would be directed by his son Jack.[126] When asked of his opinions on Scream in an interview, Osbourne announced that he was "already thinking about the next album". Osbourne's current drummer, Tommy Clufetos, has reflected this sentiment, saying that "We are already coming up with new ideas backstage, in the hotel rooms and at soundcheck and have a bunch of ideas recorded".[127] In October 2014, Osbourne released Memoirs of a Madman, a collection celebrating his entire solo career. A CD version contained 17 singles from across his career, never before compiled together. The DVD version contained music videos, live performances, and interviews.[128]

New music and touring

In August 2015, Epic Records president Sylvia Rhone confirmed with Billboard that Osbourne was working on another studio album;[129][130][131][132] in September 2019, Osbourne announced he had finished the album in four weeks following his collaboration with Post Malone.[133][134] In April 2017, it was announced that guitarist Zakk Wylde would reunite with Osbourne for a summer tour to mark the 30th anniversary of their first collaboration on 1988's No Rest for the Wicked.[135] The first show of the tour took place on 14 July at the Rock USA Festival in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.[136]

On 6 November 2017, Osbourne was announced as the headline act for the Sunday of the 2018 Download Festival held annually at Donington Park in Leicestershire, England. Having previously graced the main stage in previous years fronting Black Sabbath, this would be his first-ever Download headline solo appearance. The Download Festival set came as part of Osbourne's final world tour announcement that morning.[137]

On 6 February 2018, Osbourne announced that he would embark on his final world tour dubbed No More Tours II, a reference to his 1992 tour of the same name, with support from Stone Sour on the North American portion of the tour.[138] He later insisted that he would not retire, "It's 'No More Tours', so I'm just not doing world tours anymore. I'm still going to be doing gigs, but I'm not going on tour for six months at a time anymore. I'd like to spend some time at home."[139]

On 6 September 2019, Osbourne featured on the song "Take What You Want" by Post Malone. The song peaked on the Billboard Hot 100 charts at number 8, making it Osbourne's first US Top 10 single in 30 years since he was featured on Lita Ford's "Close My Eyes Forever".[140]

Ordinary Man and Patient Number 9

On 21 February 2020, Osbourne released his first solo album in almost ten years, Ordinary Man, which received positive reviews from music critics and debuted at number three on the UK Albums Chart.[141][142] A few days after the release, Osbourne told iHeartRadio that he wanted to make another album with Andrew Watt, the main producer of Ordinary Man.[143][144] One week after the release of the album, an 8-bit video game dedicated to Osbourne was released, called Legend of Ozzy.[145] Following the release Osbourne then started working on his follow up album, once again with Andrew Watt.[146] In November 2021, Sony announced that Osbourne's album would be released within six months;[147] it was also announced that Zakk Wylde will have full involvement in the album following his absence on Ordinary Man.[148]

On 24 June 2022, Osbourne announced his thirteenth album would be titled Patient Number 9 and released the title track alongside an accompanying music video that same day. The album was released on 9 September 2022.[149] Osbourne then had his first live performances in three years with two brief concerts at sporting events: on 30 August, he performed "Iron Man" and "Paranoid" at the 2022 Commonwealth Games closing ceremony in Birmingham, joined by Iommi and former touring members of Black Sabbath Tommy Clufetos and Adam Wakeman;[150][151] and on 8 September, at the 2022 NFL Kickoff held at Inglewood's SoFi Stadium, Osbourne performed both "Patient Number 9" and "Crazy Train", with his backing band being Zakk Wylde, Tommy Clufetos, Chris Chaney and the album's producer Andrew Watt.[152]

No More Tours II tour

In January 2023, Osbourne announced that the European leg of the No More Tours II would be cancelled after almost two years of being postponed. Osbourne effectively retired from touring, citing his accident in 2019 which resulted in the singer suffering spinal damage, while affirming his plan to continue smaller-scale live performances as his health permitted.[153][154] In September 2023, he revealed that he was working on a new album with a planned 2024 release while also preparing to go on the road following a successful spinal surgery earlier that month.[155]

In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked Osbourne at number 112 on its list of the 200 Greatest Singers of All Time.[156]

Other work

Ozzfest

Osbourne's biggest financial success of the 1990s was a venture named Ozzfest, created and overseen by his wife and manager Sharon and assisted by his son Jack, after Ozzy was turned down by the organisers of the Lollapalooza festival.[157][158] The first Ozzfest was held in York, Pennsylvania, on 20 September 1996.[159] Ozzfest was an instant hit with metal fans, helping many up-and-coming groups who were featured there to broad exposure and commercial success.[160] Some acts shared the bill with a reformed Black Sabbath during the 1997 Ozzfest tour, with the first two shows in Bristow, Virginia and West Palm Beach, Florida.[161][162]

From its inception to 2005, more than four million people attended Ozzfest, and it grossed more than US$170 million over the same period.[163] The festival helped promote many new hard rock and heavy metal acts of the late 1990s and early 2000s.[164] Ozzfest helped Osbourne to become the first hard rock and heavy metal star to hit $50 million in merchandise sales.[165] In 2005, Osbourne and his wife Sharon starred in an MTV competition reality show entitled Battle for Ozzfest. A number of yet unsigned bands send one member to compete in a challenge to win a spot on the 2005 Ozzfest and a possible recording contract.[166][167] During Ozzfest 2005, after having missed several shows due to ill health, Osbourne announced that he was retiring from the event.[168] He did in fact return to Ozzfest in 2006, but with a reduced schedule, leaving many of the concerts to be closed by System of a Down instead of himself.[169]

Tickets for the 2007 tour were offered to fans free of charge, which led to some controversy.[clarification needed][170] In 2008, Ozzfest was reduced to a one-day event in Dallas, where Osbourne played, alongside Metallica and King Diamond.[171] In 2010, the tour opened with a Jersey Shore spoof skit starring Osbourne.[172] Osbourne appeared as the headliner closing the show after opening acts Halford and Mötley Crüe. The tour, though small (only six US venues and one UK venue were played), generated rave reviews.[173][174][175][176]

Television

Osbourne achieved greater celebrity status through the MTV reality television series The Osbournes. Created by his wife Sharon, the show follows the home life of Ozzy Osbourne and his family (wife Sharon, children Jack and Kelly, occasional appearances from his son Louis, but eldest daughter Aimee did not participate). The programme became one of MTV's greatest hits. It premiered on 5 March 2002, and the final episode aired on 21 March 2005.[177]

The success of The Osbournes led Osbourne and the rest of his family to host the 30th Annual American Music Awards in January 2003.[178][179] The night was marked with constant "bleeping" due to some of the lewd and raunchy remarks made by Ozzy and Sharon Osbourne. Presenter Patricia Heaton walked out midway in disgust.[180] On 20 February 2008, Ozzy, Sharon, Kelly and Jack Osbourne hosted the 2008 BRIT Awards held at Earls Court, London.[181] Ozzy appeared in a TV commercial for I Can't Believe It's Not Butter! which began airing in the UK in February 2006.[182]

Osbourne appears in a commercial for the online video game World of Warcraft.[183] He was also featured in the music video game Guitar Hero World Tour as a playable character. He becomes unlocked upon completing "Mr. Crowley" and "Crazy Train" in the vocalist career. The 2002 dark fantasy combat flight simulator Savage Skies was initially developed under the title Ozzy's Black Skies and was to feature his likeness as well as songs from both his stint in Black Sabbath as well as his solo career,[184][185] but licensing issues forced developer iRock Interactive to re-tool the game and release it without the Osbourne branding.[186]

In October 2009, Osbourne published I Am Ozzy, his autobiography.[187] He said ghost writer Chris Ayres told him he had enough material for a second book. A film adaptation of I Am Ozzy is also in the works,[needs update] and Osbourne said he hoped "an unknown guy from England" will get the role over an established actor, while Sharon stated she would choose established English actress Carey Mulligan to play her.[188]

A documentary film about Osbourne's life and career, entitled God Bless Ozzy Osbourne, premiered in April 2011 at the Tribeca Film Festival and was released on DVD in November 2011.[189] The film was produced by Osbourne's son Jack.[190] On 15 May 2013 Osbourne, alongside the current members of Black Sabbath, appeared in an episode of CSI: Crime Scene Investigation titled "Skin in the Game". The History Channel premiered a comedy reality television series starring Ozzy Osbourne and his son Jack Osbourne on 24 July 2016, named Ozzy & Jack's World Detour.[191] During each episode Ozzy and Jack visit one or more sites to learn about history from experts, and explore unusual or quirky aspects of their background.

Osbourne appeared in a November 2017 episode of Gogglebox alongside other UK celebrities such as Ed Sheeran, former Oasis frontman Liam Gallagher, and Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn as part of Channel 4 and Cancer Research UK's Stand Up to Cancer fundraising campaign.[192] In November 2017, Osbourne signed on as an ambassador of the rock-themed online Metal Casino, founded by metal music fans in August 2017.[193] In February 2019, Osbourne's merchandising partner announced that Ozzy would have his own branded, online slots game as part of the NetEnt Rocks music-themed portfolio.[194]

In 2020, Osbourne voiced King Thrash, king of the rock trolls, for the animated movie Trolls World Tour.[195]

Controversies

Ozzy Osbourne courted controversy throughout his career. He adopted the title "Prince of Darkness", took on a demonic stage persona, and portrayed himself as the "Madman of Rock".[196] Many Christian religious groups accused Osbourne of being a Devil worshipper, of promoting Satanism, and of being a harmful influence on teenagers.[196] He was demonised by Protestant fundamentalists such as Jeff Godwin,[196] and by Catholics such as Cardinal John O'Connor, who called his music "a help to the devil".[197] Osbourne denied being a Satanist and "responded with defiance by simply absorbing the charges into his stage persona".[196] He also struck back by mocking the Christian right in his lyrics, such as the song "Miracle Man".[196] Scholar Christopher M. Moreman compared the controversy to those levelled against the occultist Aleister Crowley. Both were demonised by the media and Christian groups. Osbourne tempted the comparison with his 1980 song "Mr. Crowley".[196][198]

In 1981, after signing his first solo record deal, Osbourne bit the head off a dove during a meeting with CBS Records executives in Los Angeles.[199] Apparently, he had planned to release doves into the air as a sign of peace, but due to intoxication, he instead grabbed a dove and bit its head off. He then spat the head out,[199][200] with blood still dripping from his lips. As security was escorting Osbourne out of the building, he grabbed a second dove and also bit its head off. Due to its controversy, the head-biting act has been parodied and alluded to several times throughout his career and is part of what made Osbourne famous.[201]

"I'm like the Dennis the Menace kind of crazy. Fun crazy, I hope."

On 20 January 1982, Osbourne bit the head off a bat[203] that he thought was rubber while performing at the Veterans Memorial Auditorium in Des Moines, Iowa. According to a 2004 Rolling Stone article, the bat was alive at the time;[204] however, 17-year-old Mark Neal, who threw it onto the stage, said it was brought to the show dead.[199] According to Osbourne in the booklet to the 2002 edition of Diary of a Madman, the bat was not only alive but managed to bite him, resulting in Osbourne being vaccinated against rabies. On 20 January 2019, Osbourne commemorated the 37th anniversary of the bat incident by offering an "Ozzy Plush Bat" toy "with detachable head" for sale on his personal web-store. The site claimed the first batch of toys sold out within hours.[205]

On New Year's Eve 1983, Canadian teenager James Jollimore murdered a woman and her two sons in Halifax, Nova Scotia, reportedly after listening to "Bark at the Moon". A friend of Jollimore told the court: "Jimmy said that every time he listened to the song, he felt strange inside ... He said when he heard it on New Year's Eve, he went out and stabbed someone".[206]

In 1984, California teenager John McCollum committed suicide while listening to Osbourne's "Suicide Solution". His parents sued Osbourne (McCollum v. CBS),[207] alleging that the song encouraged their son to kill himself. The prosecutors highlighted the lyrics "Where to hide, suicide is the only way out", and claimed that the song also contained subliminal and backmasked messages encouraging suicide. The courts ruled in Osbourne's favour, saying there was no connection between the song and McCollum's suicide. In 1990, Osbourne was similarly sued over the suicides of two other young Americans, Michael Waller (1986) and Harold Hamilton (1988), who allegedly were listening to the song when they ended their lives.[208] The courts once again ruled in Osbourne's favour.[209] The lyrics of "Suicide Solution" were written by bandmate Bob Daisley. Osbourne said that the song was about the alcohol-related death of singer Bon Scott and was a warning against the slow suicide of alcoholism.[210]

On 18 February 1982, while wearing his future wife Sharon's dress for a photoshoot near the Alamo, Osbourne drunkenly urinated on the Alamo Cenotaph erected in honour of those who died at the Battle of the Alamo in Texas, across the street from the actual building.[211] A police officer arrested Osbourne,[201] and he was subsequently banned from the city of San Antonio for a decade.[212]

In lawsuits filed in 2000 and 2002 which were dismissed by the courts in 2003, former band members Bob Daisley, Lee Kerslake, and Phil Soussan stated that Osbourne was delinquent in paying them royalties and had denied them due credit on albums they played on.[213][214] In November 2003, a Federal Appeals Court unanimously upheld the dismissal by the US District Court for the Central District of California of the lawsuit brought by Daisley and Kerslake. The US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that Osbourne did not owe any royalties or credit to the former band members, who were let go in 1981.[215] To resolve further issues, Ozzy's manager and wife Sharon chose to replace Daisley and Kerslake's contributions on the original masters, replacing them with Robert Trujillo on bass and Mike Bordin on drums. The albums were then reissued.[216] The original tracks were restored for the 30th anniversary of the albums.

In July 2010, Osbourne and Tony Iommi decided to discontinue court proceedings over ownership of the Black Sabbath trademark. As reported to Blabbermouth, "Both parties are glad to put this behind them and to cooperate for the future and would like it to be known that the issue was never personal, it was always business."[217]

Osbourne admitted to shooting 17 of his own pet cats during a drug-fuelled rampage in the 1980s.[218][219]

Personal life

Osbourne had more than 15 tattoos, the earliest of which were the letters O-Z-Z-Y across the knuckles of his left hand. He created this himself as a teenager with a sewing needle and pencil lead.[16]

A longtime fan of the comedy troupe Monty Python, in a 2010 interview with Us Weekly Osbourne stated, "My favourite movie is Monty Python's Life of Brian".[220]

Osbourne suffered minor burns after a small house fire at his family home in Beverly Hills in January 2013.[221]

On his 65th birthday on 3 December 2013, he asked fans to celebrate his birthday by donating to the Royal Marsden cancer charity in London.[222]

In 2002, Osbourne and wife Sharon were invited to the White House Correspondents' Association dinner by Fox News Channel correspondent Greta Van Susteren for that year's event. President George W. Bush noted Osbourne's presence by joking, "The thing about Ozzy is, he's made a lot of big hit recordings – 'Party with the Animals', 'Sabbath Bloody Sabbath', 'Facing Hell', 'Black Skies' and 'Bloodbath in Paradise'. Ozzy, Mom loves your stuff."[223]

Relationships

Osbourne had six children; three from his first marriage and three from his marriage to Sharon Osbourne.[224][225]

In 1971, Osbourne met his first wife Thelma Riley at the Rum Runner, the Birmingham nightclub where she worked.[19] They were married later that year and children Jessica and Louis were soon born. Osbourne also adopted Riley's five-year-old son Elliot from a previous relationship.[226] Osbourne later referred to his first marriage as "a terrible mistake".[19] His use of alcohol and other drugs, coupled with his frequent absences while touring with Black Sabbath, took their toll on his family life; his children later complained that he was not a good father. In the 2011 documentary film God Bless Ozzy Osbourne, produced by his son Jack, Osbourne admitted that he could not even remember when Louis and Jessica were born.[227] Louis later made cameo appearances in The Osbournes.[224] He and Jessica are both actors.[224]

Osbourne began to date his manager Sharon Arden. Guitarist Randy Rhoads predicted in 1981 that the couple would "probably get married someday" despite their constant bickering and the fact that Osbourne was still married to Thelma at the time.[83] Ozzy and Sharon married on 4 July 1982. He later confessed that the Independence Day date was chosen so that he would never forget his anniversary. The couple had three children together: Aimee (born 2 September 1983), Kelly (born 27 October 1984), and Jack (born 8 November 1985).[224] After Jack's birth, Osbourne had a vasectomy.[228] Osbourne had many grandchildren.[229]

Osbourne wrote a song for his daughter Aimee, which appeared as a B-side on his seventh studio album Ozzmosis (1995). At the end of the song, she can be heard saying "I'll always be your angel", referring to the song's chorus lyrics. The song "My Little Man", which appears on Ozzmosis, was written about his son Jack. He and his family divided time between homes in Buckinghamshire[230] and Los Angeles.[231]

Religion

Osbourne said in 2018, "I never talk religion. I don't understand organised religion. But I strive to be good, although it feels good to be bad, sometimes".[232] Certain Christian groups and ministers long denounced Osbourne as an immoral Satanist, which he always dismissed. He responded by mocking the Christian right in some of his lyrics, and parodied Christian evangelists in the film Trick or Treat.[196] In 2022, Osbourne said he felt like he had a "symbiotic" relationship with evangelists: "I've kept them in jobs".[232] He recalled that he once jokingly joined Christians who were protesting outside his gig: "I joined them at the end of the line with a broomstick, and stapled on 'Have a Nice Day' and a smiley face on it. They didn't know I was there".[232]

Osbourne said in a 1986 interview, "I'm a Christian. I was christened as a Christian. I used to go to Sunday school. I never took much interest in it because...I didn't". In a later 1992 interview, he said "I believe in God. I don't go to church, but I don't think you have to go to church to believe in God."[233] The New York Times reported in 1992 that he was a member of the Church of England and prayed before each show.[234]

Political views

Osbourne wrote in his 2009 autobiography, "I'm not so comfortable with politicians". He recalled meeting former British Prime Minister Tony Blair at an awards show: "I couldn't get over the fact that our young soldiers were dying out in the Middle East and he could still find the time to hang around with pop stars".[235] Osbourne was critical of Donald Trump. He said the US president was "acting like a fool" with his response to COVID-19.[235] He added "If I was running for president, I would try and find out a little bit about politics. Because the fucking guy you've got in there now doesn't know that much about it".[235] In 2020, after Trump used Osbourne's song in his campaign, he issued a statement forbidding Trump, or any other campaign, from using his music without approval.[235] In 2024, Osbourne said "Donald Trump is a felon, right? Correct me if I'm wrong, felons can't own a gun. He can't own a gun, but he could start World War III on his own".[236]

Jacob Held said that Osbourne's viewpoint was anti war in general, but that he didn't object to using proportionate means in just wars. As an example, Held shows that in the song "War Pigs", Osbourne sang against the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as excessive, but in the song "Thank God for the Bomb" he supports the policy of nuclear deterrence in the Cold War.[237]

In 2022, Osbourne expressed his support for Ukraine following Russia's full-scale invasion of the country. That year, he dedicated his album Patient Number 9 to Ukraine, and pledged to donate all proceeds to the Third Wave Volunteers organisation.[238] Ozzy and his wife Sharon announced they planned to host two families of Ukrainian refugees at their Buckinghamshire estate.[239]

Ozzy's wife Sharon, who identifies as Jewish, said shortly after the October 7 attacks on Israel, "Ozzy is so confused by it all and just keeps asking me to explain why there is so much hatred of Jews".[240] Around this time, Osbourne said he did not want any association with Kanye West, due to his antisemitism.[241] In 2024, following calls for a cultural boycott of Israeli artists, Ozzy and Sharon were among those who signed an open letter by Creative Community For Peace, in "support of freedom of expression and against discriminatory boycotts".[242] In 2025, Ozzy and Sharon were among those who signed an open letter calling for an investigation into alleged anti-Israel bias in the BBC's coverage of the Gaza war.[243][244][245]

Views on the LGBTQ+ community

Osbourne has been publicly supportive of the LGBTQ+ community, having been friends with prominent LGBTQ musicians such as Elton John and Yungblud.[246] In 1989 he personally apologised for homophobic remarks made by Zakk Wylde at a concert in Long Beach, Los Angeles and reportedly donated to AIDS Walk Long Beach, a fundraising event dedicated to HIV/AIDS research.[247][246]

In 2010 Osbourne expressed disgust at the Westboro Baptist Church when they sang a parody of the song "Crazy Train" for a picket they held during the Snyder v. Phelps Supreme Court hearing with lyrics promoting their ideology, stating “I am sickened and disgusted by the use of ‘Crazy Train’ to promote messages of hate and evil by a ‘church.'”[246]

Drug use

Osbourne used tobacco, alcohol, street drugs such as cocaine, and prescription drugs for most of his adult life. He admitted to Sounds in 1978, "I get high, I get fucked up ... what the hell's wrong with getting fucked up? There must be something wrong with the system if so many people have to get fucked up ... I never take dope or anything before I go on stage. I'll smoke a joint or whatever afterwards."[248] Black Sabbath bandmate Tony Iommi said that while all the band drank alcohol and took other illicit drugs in the 1970s, Osbourne had the unhealthiest lifestyle of them all. Despite this, said Iommi, he was typically the only one left standing when the others were "out for the count".[54] Upon being fired from Black Sabbath in 1979, Osbourne spent the next three months locked in his hotel room drinking alcohol and taking vast amounts of drugs "all day, every day."[249][23][24]

Osbourne later commented on his former wild lifestyle, expressing bewilderment at his own survival through 40 years of misusing tobacco, alcohol, street drugs, and prescription drugs.[250] Longtime guitarist Zakk Wylde has attributed Osbourne's longevity in spite of decades of substance abuse to "a very special kind of fortitude that's bigger than King Kong and Godzilla combined... seriously, he's hard as nails, man!"[251]

Osbourne's first experience with cocaine was in early 1971 at a hotel in Denver, Colorado, after a show Black Sabbath had done with Mountain.[19] He states that Mountain's guitarist, Leslie West, introduced him to the drug.[19] Though West was reluctant to take credit for introducing Osbourne to cocaine, Osbourne remembered the experience quite clearly: "When you come from Aston and you fall in love with cocaine, you remember when you started. It's like having your first fuck!"[19] Osbourne said that upon first trying the drug, "The world went a bit fuzzy after that."[19]

Osbourne's substance abuse, at times, caused friction within his band. Don Airey, keyboardist for Osbourne during his early solo career, said that these issues were what ultimately caused him to leave the band.[252] In his memoir Off the Rails, former bassist Rudy Sarzo detailed the frustrations felt by him and his bandmates as they coped with life on the road with Osbourne, who was in a state of near-constant inebriation and was often so hungover that he would refuse to perform. When he was able to perform, his voice was often so damaged from his smoking, drinking, and drug abuse that the performance suffered. Many shows on the American leg of the 1981–82 Diary of a Madman tour were simply cancelled, and the members of his band quickly began to tire of the unpredictability, coupled with the often violent mood swings he was prone to when either drunk or high.[83]

Osbourne claimed that he would have died if Sharon had not offered to manage him as a solo artist.[253]

Osbourne claimed in his autobiography that he was invited in 1981 to a meeting with the head of CBS Europe in Germany. Intoxicated, he decided to lighten the mood by performing a striptease on the table and then kissing the record executive on the lips. According to his wife Sharon, he had actually performed a goose-step up and down the table and urinated in the executive's wine, but was too drunk to remember.[51]

In February 1982, Osbourne drunkenly fired his entire band, including Randy Rhoads, after they had informed him that they would not participate in a planned live album of Black Sabbath songs. He also physically attacked Rhoads and Rudy Sarzo in a hotel bar that morning, and Sharon informed the band that she feared he had "finally snapped". Osbourne later had no memory of firing his band and the tour continued, though his relationship with Rhoads never fully recovered due to Rhoads's death in a plane crash a month later.[83] In May 1984, Osbourne was arrested in Memphis, Tennessee, again for public intoxication.[254] The most notorious incident came in August 1989, when Sharon claimed that Ozzy had tried to strangle her after returning home from the Moscow Music Peace Festival, in a haze of alcohol and other drugs.[255] The incident led Ozzy to six months in rehabilitation, after which time, Sharon regained her faith in her husband and did not press charges.[256]

In 2003, Osbourne told the Los Angeles Times how he was nearly incapacitated by medication prescribed by a Beverly Hills doctor.[257] The doctor was alleged to have prescribed 13,000 doses of 32 drugs in one year.[258] However, after a nine-year investigation by the Medical Board of California, the Beverly Hills physician was exonerated of all charges of excessive prescribing.[259]

Osbourne managed to remain clean and sober for extended periods in the late 2000s.[260]

In 2010, during an interview on The Howard Stern Show, Ozzy said that it took him 19 attempts to get his driving licence because of his alcohol use.[261]

At the TEDMED Conference in October 2010, scientists from Knome, a Massachusetts human genome interpretation company, joined Osbourne on stage to discuss their analysis of Osbourne's whole genome, which shed light on how the famously hard-living rocker had survived decades of misusing alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs.[262]

In April 2013, Osbourne revealed through Facebook that he had resumed smoking, drinking, and doing drugs for the past year and a half, stating he "was in a very dark place" but said he had been sober again since early March. He also apologised to Sharon, his family, friends, bandmates and his fans for his "insane" behaviour during that period.[263] In a February 2021 interview with Variety, Ozzy and his son Jack (who has been sober for 17 years) opened up about their recovery. Ozzy revealed he had been sober for about seven years.[264]

Health issues

Osbourne was dyslexic,[265] and suggested he may have had ADHD.[265][266]

Osbourne experienced tremors for some years and linked them to his continuous drug abuse. In 2003, he found out it was a genetic form of Parkinson's disease. Osbourne had to take daily medication for the rest of his life to combat the involuntary shudders associated with the condition.[267] He publicly revealed the Parkinson's diagnosis in January 2020, saying, "I'm not dying from Parkinson's. I've been working with it most of my life."[268] Osbourne also showed symptoms of mild hearing loss, as depicted in the television show, The Osbournes, where he often asked his family to repeat what they say.

On 6 February 2019, Osbourne was hospitalised in an undisclosed location on his doctor's advice due to flu complications, postponing the European leg of his "No More Tours II" tour. The issue was described as a "severe upper-respiratory infection" following a bout with the flu which his doctor feared could develop into pneumonia, given the physicality of the live performances and an extensive travel schedule throughout Europe in winter conditions.[269]

By 12 February 2019, Osbourne had been moved to intensive care. Tour promoters Live Nation said that they were hopeful that Osbourne would be "fit and healthy" and able to honour tour dates in both Australia and New Zealand in March.[270] Osbourne later cancelled the tour entirely, and ultimately all shows scheduled for 2019, after sustaining serious injuries from a fall in his Los Angeles home while still recovering from pneumonia.[271] In February 2020, Osbourne cancelled the 2020 North American tour, seeking treatment in Switzerland until April.[272] In 2020, Osbourne also revealed that he had emphysema.[273]

By 2025, he had lost his ability to walk due to Parkinson's disease.[274]

Death and funeral

Osbourne died at his home in Buckinghamshire on the morning of 22 July 2025, aged 76, surrounded by his family,[275][276] just 17 days after the Back to the Beginning farewell concert.[277] His primary cause of death was ruled as acute myocardial infarction (heart attack) and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, with coronary artery disease and Parkinson's disease with autonomic dysfunction listed as associated factors.[278]

A number of public figures and musicians shared tributes. Elton John referred to him as "a dear friend and a huge trailblazer who secured his place in the pantheon of rock gods – a true legend."[279]

On 30 July, his funeral cortege left Villa Park, passing Osbourne's childhood home on Lodge Road, and proceeded to Broad Street, which was closed to traffic.[280][281] It stopped at the Black Sabbath Bridge where Osbourne's family viewed flowers and messages left by fans, and met with the Lord Mayor.[280][282] The cortege then passed by the Black Sabbath mural on Navigation Street and The Crown where Black Sabbath played their first concert.[280] Tens of thousands of people gathered along the route to observe.[280] That same day, the Band of the Coldstream Guards performed Black Sabbath's "Paranoid" during the Changing of the Guard ceremony at Buckingham Palace. The performance was widely interpreted as a tribute and noted for its departure from the event's traditional repertoire.[283] A private funeral was held the following day,[284] attended only by his family and a select gathering of rock stars, including Marilyn Manson, Rob Zombie, Zakk Wylde, James Hetfield, and his Black Sabbath bandmates. In accordance with his wishes, Osbourne was interred on the grounds of Welders House near a "beautiful" lake.[285][286]

Legacy

Osbourne is considered an icon of hard rock music, and one of the founders of heavy metal music through his work with Black Sabbath. He has been referred to as the "Godfather of Heavy Metal"[4] and the "Madman of Rock".[196] He disliked being categorised as metal, stating that while his band "plays heavy", other bands that are considered metal are "really heavy". "When you get pigeonholed with a certain [genre], it can be very difficult to do something a bit lighter or an acoustic track or whatever you want to do. Back in the day, it was always just rock music. It's still just rock music."[287][288]

Outside of music, Osbourne and his family's show The Osbournes is regarded as a pioneering reality television programme which ushered in an era of shows focusing on celebrity family life.[289]

Band members

Final members:

- Ozzy Osbourne – vocals (1979–1992, 1994–2025)

- Zakk Wylde – lead guitar, backing vocals (1987–1992, 1995, 1998, 2001–2004, 2006–2009, 2017–2025)

- Mike Inez – bass (1989–1992, 1996, 1998, 2025)

- Adam Wakeman – keyboards, rhythm guitar (2004–2025)

- Tommy Clufetos – drums (2010–2025)

Awards

Osbourne received several awards for his contributions to the music community. In 1994, he was awarded a Grammy Award for the track "I Don't Want to Change the World" from Live & Loud for Best Metal Performance of 1994.[94] At the 2004 NME Awards in London, Osbourne received the award for Godlike Genius.[290] In 2005 Osbourne was inducted into the UK Music Hall of Fame both as a solo artist and as a member of Black Sabbath.[291] In 2006, he was inducted into the US Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with Black Sabbath bandmates Tony Iommi, Bill Ward, and Geezer Butler.[292] In 2024, Osbourne was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame for his solo career.[293][294]

In 2007, Osbourne was honoured at the second annual VH1 Rock Honors, alongside Genesis, Heart, and ZZ Top. In addition, that year a bronze star honouring Osbourne was placed in the Birmingham Walk of Stars on Broad Street in the city centre.[295] He was presented the award by the Lord Mayor of Birmingham on 6 July.[295] "I am really honoured", he said, "All my family is here and I thank everyone for this reception—I'm absolutely knocked out".[295]

In 2008, Osbourne was crowned with the prestigious Living Legend award in the Classic Rock Roll of Honour Awards. Past recipients include Alice Cooper, Lemmy, and Jimmy Page. Slash, the former Guns N' Roses guitarist, presented the award.[296] In 2010 Osbourne won the "Literary Achievement" honour for his memoir, I Am Ozzy, at the Guys Choice Awards at Sony Pictures Studio in Culver City, California. Osbourne was presented with the award by Ben Kingsley. The book debuted at No. 2 on the New York Times's hardcover non-fiction best-seller list.[297] Osbourne was also a judge for the 6th,[298] 10th and 11th[299] annual Independent Music Awards to support independent artists' careers. In May 2015, Osbourne received the Ivor Novello Award for Lifetime Achievement from the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors at a ceremony held at the Grosvenor House Hotel, London.[300] In 2016, Osbourne attended the naming of a Midland Metro tram after him in Birmingham.[301]

In April 2021, Osbourne was inducted into the celebrity wing of the WWE Hall of Fame for his various appearances, notably for his appearance at WrestleMania 2 in 1986 when he and Lou Albano managed The British Bulldogs (Davey Boy Smith and The Dynamite Kid) in their WWF Tag Team Championship win over The Dream Team (Greg Valentine and Brutus Beefcake).[302]

On 30 June 2025, one week before their farewell "Back to the Beginning" concert, Osbourne and the other original members of Black Sabbath were each made Freemen of the City of Birmingham.[303]

Discography

|

Solo studio albums

|

Black Sabbath studio albums

|

Tours

- Polka Tulk Blues/Earth Tour 1968–1969 – with Black Sabbath

- Black Sabbath Tour 1970 – with Black Sabbath

- Paranoid Tour 1970–1971 – with Black Sabbath

- Master of Reality Tour 1971–1972 – with Black Sabbath

- Vol. 4 Tour 1972–1973 – with Black Sabbath

- Sabbath Bloody Sabbath Tour 1973–1974 – with Black Sabbath

- Sabotage Tour 1975–1976 – with Black Sabbath

- Technical Ecstasy Tour 1976–1977 – with Black Sabbath

- Never Say Die! Tour 1978 – with Black Sabbath

- Blizzard of Ozz Tour (1980–1981) – as solo artist

- Diary of a Madman Tour (1981–1982) – as solo artist

- Speak of the Devil Tour (1982–1983) – as solo artist

- Bark at the Moon Tour (1983–1985) – as solo artist

- The Ultimate Sin Tour (1986) – as solo artist

- No Rest for the Wicked Tour (1988–1989) – as solo artist

- Theatre of Madness Tour (1991–1992) – as solo artist

- No More Tours Tour (1992) – as solo artist

- Retirement Sucks Tour (1995–1996) – as solo artist

- Ozzfest Tour 1997 – with Black Sabbath

- The Ozzman Cometh Tour (1998) – as solo artist

- European Tour 1998 – with Black Sabbath

- Reunion Tour 1998–1999 – with Black Sabbath

- Ozzfest Tour 1999 – with Black Sabbath

- US Tour 1999 – with Black Sabbath

- European Tour 1999 – with Black Sabbath

- Ozzfest Tour 2001 – with Black Sabbath

- Ozzfest Tour 2004 – with Black Sabbath

- Merry Mayhem Tour (2001) – as solo artist[304]

- Down to Earth Tour (2002) – as solo artist

- European Tour 2005 – with Black Sabbath

- Ozzfest Tour 2005 – with Black Sabbath

- Black Rain Tour (2008) – as solo artist

- Scream World Tour (2010–2011) – as solo artist

- Black Sabbath Reunion Tour, 2012–2014 – with Black Sabbath[305]

- Ozzy and Friends Tour (2012; 2015) – as solo artist

- The End Tour – with Black Sabbath 2016–2017

- No More Tours II (2018) – as solo artist[306]

- Back to the Beginning (2025) – as solo artist and with Black Sabbath

References

- ^ "Black Sabbath". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 16 August 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ "Ozzy Osbourne Stares Down His Demons with a Smile on 'Ordinary Man'". Rolling Stone. 21 February 2020.

- ^ Von Bader, David (30 July 2013). "Ozzy Osbourne, the Prince of Darkness, on His Nickname: "It's Better Than Being Called an Asshole"". Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ a b E. B. Christian, ed., Rock Brands: Selling Sound in a Media Saturated Culture (Lexington Books, 2010), ISBN 0-7391-4636-X, p. 45.

- ^ Wall, Mick (1986). Diary of a Madman – The Official Biography. Zomba Books.

- ^ Ozzy Osbourne To Receive Billboard's Legend Of Live Award Billboard; retrieved 8 December 2010

- ^ "Black Sabbath". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ "Ozzy Osbourne". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ Chad (25 October 2019). "Ozzy Osbourne". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ Queenborough, Marcus (29 July 2023). "Ozzy Osbourne in Birmingham - looking back at the Brummie behind the bull". Birmingham Mail. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ a b Weber, Barry (2007). "Ozzy Osbourne Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ Cannon, Matt (7 August 2018). "Ozzy Osbourne's birth certificate reveals his first home in Birmingham - and it's not in Aston". Birmingham Mail. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ I Am Ozzy, page 6

- ^ Oseary, Guy (2004). On the Record: Over 150 of the Most Talented People in Music Share the Secrets of Their Success. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-200304-6.

- ^ "Time and place: Ozzy Osbourne". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Sue Crawford (2003), "Ozzy Unauthorized"; ISBN 978-1-84317-016-7

- ^ a b Johnson, Ross (January 2005). "What I've Learned: Ozzy Osbourne". Esquire. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ "Sisters reveal the real Ozzy Osbourne". Birmingham Live. 12 October 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Osbourne, Ozzy; Ayres, Chris (2010). I Am Ozzy. Grand Central Publishing. pp. 14, 84. ISBN 978-0-446-56989-7.

- ^ "Profiles of Ozzy Osbourne, Elvis Costello, David Bowie, Norah Jones". CNN. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Why is the Birmingham accent so difficult to mimic?". BBC. 12 December 2016.

- ^ Susman, Gary (1 December 2003). "Ozzy Osbourne reveals childhood sexual abuse". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ a b The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll (3rd, rev. and updated for the 21st century ed.). New York: Fireside. 2001. ISBN 9780743201209.

- ^ a b "Ozzy Osbourne, superstar -- again". CNN.com. CNN. 12 April 2002. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ GQ interview

- ^ "Cynthia Ellis: Q&A With Jack Osbourne for God Bless Ozzy Osbourne". Huffingtonpost.com. 26 May 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ Lynch, Joseph Brannigan (25 April 2011). "'God Bless Ozzy Osbourne': New documentary presents the life, art, and addiction of the metal madman". The Music Mix. Entertainment Weekly/CNN. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ Osbourne, Ozzy (2009). I Am Ozzy. p. 41.

- ^ a b Ankeny, Jason. "Biography-Geezer Butler". Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ^ Osbourne, Ozzy (2010). I Am Ozzy.

- ^ a b c d Ruhlmann, William. "AMG Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ a b c "RIAA Gold & Platinum database-"Master of Reality"". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on 8 August 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ "Master of Reality Rolling Stone Review". Rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ "Black Sabbath "Vol. 4" - An Observation Of Rarity -". honormusicawards.com. 18 August 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum - Black Sabbath Vol. 4". RIAA.

- ^ Fletcher, Gordon. "Sabbath, Bloody Sabbath Album Review". 14 February 1974. Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Sabbath, Bloody Sabbath AMG Review". AllMusic. Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- ^ "RIAA Gold & Platinum database-Sabbath Bloody Sabbath". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ Altman, Billy (25 September 1975). "Sabotage Album Review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 31 December 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "Sabotage AMG Album Review". AllMusic. Retrieved 20 March 2008.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "Technical Ecstasy AMG Review". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- ^ Everley, Dave (12 January 2025). ""We really weren't compatible. It was kind of cool, but there was a lot left to be desired": The singer who briefly replaced Ozzy Osbourne in Black Sabbath in 1977 – and then was forgotten". Louder. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ Sarfas, Pete (March 2005). "Necromandus". alexgitlin.com.

- ^ "Bob Daisley's History with the Osbournes". Bobdaisley.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ Everley, Dave (24 March 2024). "The story of Ozzy's forgotten 1970s "prog rock" solo band". Louder. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ "Cumbrian Bands of the Seventies: Necromandus". Btinternet.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Hoskyns, Barney (2009). "Into the Void: Ozzy Osbourne and Black Sabbath". Omnibus Press.

- ^ Sharpe-Young, Garry. "MusicMight.com Black Sabbath Biography". MusicMight.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "1978 Tour — Black Sabbath Online". Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Osbourne, Ozzy; Ayres, Chris (2010). I Am Ozzy. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-56989-7.

- ^ a b Osbourne, Ozzy (2011). I Am Ozzy. I Am Ozzy. ISBN 9780446573139. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ Ronnie James Dio interview with Tommy Vance for BBC Radio 1's Friday Rock Show; broadcast 21 August 1987; transcribed by editor Peter Scott for Sabbath fanzine Southern Cross No. 11, October 1996, p27

- ^ ""Heavy Metal"". Seven Ages of Rock. 5 March 2009. 8 minutes in. Yesterday.

- ^ a b Iommi, Tony (2011). Iron Man: My Journey Through Heaven and Hell With Black Sabbath. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306819551.

- ^ a b Elliott, Paul (February 1998). "Paranoid? Who's asking?". Q #137. p. 27.

- ^ "Black Sabbath Reunion Tour". ozzy.com. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Black Sabbath – Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ "Black Sabbath – Biography". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ "Black Sabbath announce new album, world tour". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 November 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "Reunited Black Sabbath play Birmingham gig". BBC News. 21 May 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ "Black Sabbath: New Album Title Announced; Recording Drummer Revealed". Blabbermouth.Net. 12 January 2013. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (19 June 2013). "Black Sabbath Earns First No. 1 Album on Billboard 200 Chart". Billboard. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ Lane, Daniel (16 June 2013). "Black Sabbath make chart history with first Number 1 album in nearly 43 years". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ "Black Sabbath Set Last U.S. Show". Rolling Stone. 9 June 2016. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Accomazzo, David (22 September 2016). "Black Sabbath's Final Tour Ended In Rare Form in Phoenix Last Night". Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Ozzy expects to 'shed a few tears' at Black Sabbath farewell show". BBC. 10 December 2017.

- ^ "Black Sabbath To Bring 'The End' Tour To The UK And Ireland". Stereoboard.com. 10 June 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "Commonwealth Games: Ozzy Osbourne surprise appearance headlines Birmingham 2022 closing ceremony". BBC News. 8 August 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "Black Sabbath's Ozzy Osbourne, Tony Iommi Reunite for Commonwealth Games". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ "Sharon Osbourne announces Ozzy's final show: 'This is his full stop'". BBC. 5 February 2025. Retrieved 5 February 2025.

- ^ Hann, Michael (5 July 2025). "Black Sabbath and Ozzy Osbourne: Back to the Beginning review – all-star farewell to the gods of metal is epic and emotional". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 July 2025.

- ^ Peplow, Gemma (6 July 2025). "Ozzy Osbourne reunites with Black Sabbath for 'final bow' in emotional metal goodbye". Sky News. Retrieved 6 July 2025.

- ^ Wilding, Philip (January 2002). "Return to Ozz". Classic Rock #36. p. 52.

- ^ a b Daisley, Robert (July 2010). "Bob Daisley's History with the Osbournes". bobdaisley.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ^ Ling, Dave (July 2006). "Gimme More". Classic Rock. No. 94. p. 68.

- ^ "Unheard Randy Rhoads recordings to be released". Classic Rock Magazine. 20 March 2014. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^ "Former Ozzy Bassist Has An Axe To Grind with the Osbournes". Rockcellarmagazine.com. 13 June 2013. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ "RIAA Searchable Database-Search: Ozzy Osbourne". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ Schroer, Ron (October 1996). "Bill Ward and the Hand of Doom – Part III: Disturbing the Peace". Southern Cross (Sabbath fanzine) #18. p. 20.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time". Rolling Stone. 27 August 2003. Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ "NTSB Accident Report for Rhoads' plane crash". Planecrashinfo.com. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ a b Osbourne, Sharon (11 October 2006). "Sharon Osbourne Extreme: My Autobiography". Little Brown. ISBN 9780759568945. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d Sarzo, Rudy (2017). Off the Rails (third edition). CreateSpace Publishing. ISBN 1-53743-746-1