History of ice hockey

Ice hockey is believed to have evolved from simple stick and ball games played in the 18th and 19th centuries in Britain, Ireland, and elsewhere, primarily bandy, hurling, and shinty. The North American sport of lacrosse was also influential. These games were brought to North America and several similar winter games using informal rules developed, such as shinny and ice polo, but were later absorbed into a new organized game with codified rules which today is ice hockey.

In 2024, it was noted that the post-internet discoveries of other hockey-like games have buried modern ice hockey’s true “lineal” origins.[1] Mark Grant noted that Montreal inherited a singular version of hockey on ice that was transferred from Halifax in 1872 or 1873. This version of hockey led to the extinction of all other hockey-like games, for being based on a superior stick, the Kjipuktuk Mi'kmaw's “flat thin-blade” stick, which "tamed the puck," and Dartmouth-Canada's Acme skate, "which leveraged the skater and weaponized turning." Grant argued that all other ‘hockey’ games should not be confused with the “Halifax-Montreal” game and were “non-lineal” games that are ancillary to modern ice hockey’s true narrative. He wrote that "these other games were all "background performers in an epic story of conquest that co-starred Halifax and Montreal." "[2] [3]

Name

[edit]In England, field hockey has historically been called simply hockey and was what was referenced by first appearances in print. The first known mention spelled as hockey occurred in the 1772 book Juvenile Sports and Pastimes, to Which Are Prefixed, Memoirs of the Author: Including a New Mode of Infant Education, by Richard Johnson (Pseud. Master Michel Angelo), whose chapter XI was titled "New Improvements on the Game of Hockey".[4] The 1527 Statute of Galway banned a sport called "'hokie'—the hurling of a little ball with sticks or staves". A form of this word was thus being used in the 16th century, though much removed from its current usage.

The belief that hockey was mentioned in a 1363 proclamation by King Edward III of England[5] is based on modern translations of the proclamation, which was originally in Latin and explicitly forbade the games Pilam Manualem, Pedivam, & Bacularem: & ad Canibucam & Gallorum Pugnam.[6][7]

According to the Austin Hockey Association, the word puck derives from the Scottish Gaelic puc or the Irish poc ('to poke, punch or deliver a blow'). "...The blow given by a hurler to the ball with his camán or hurley is always called a puck."[8]

Precursors

[edit]

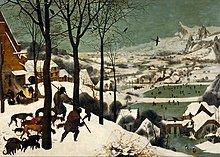

Stick-and-ball games themselves are very ancient. Games such as polo are known to have taken place in the pre-Christian era in Persia.[9] In Europe, these games included the Irish game of hurling, the closely related Scottish game of shinty and versions of field hockey (including bandy ball, played in England). IJscolf, a game resembling colf on an ice-covered surface, was popular in the Low Countries between the Middle Ages and the Dutch Golden Age. It was played with a wooden curved bat (called a colf or kolf), a wooden or leather ball and two poles (or nearby landmarks), with the objective to hit the chosen point using the fewest strokes. A similar game (knattleikr) had been played for a thousand years or more by the Scandinavian peoples, as documented in the Icelandic sagas. Polo has been referred to as "hockey on horseback".[10] In England, field hockey developed in the late 17th century, and there is evidence that some games of field hockey took place on the ice.[10] These games of "hockey on ice" were sometimes played with a bung (a plug of cork or oak used as a stopper on a barrel). William Pierre Le Cocq stated, in a 1799 letter written in Chesham, England:[11]

I must now describe to you the game of Hockey; we have each a stick turning up at the end. We get a bung. There are two sides one of them knocks one way and the other side the other way. If any one of the sides makes the bung reach that end of the churchyard it is victorious.

A 1797 engraving unearthed by Swedish sport historians Carl Gidén and Patrick Houda shows a person on skates with a stick and bung on the River Thames, probably in December 1796.[12]

According to Kenth Hansen, one precursor was bandy:

The origin of ice hockey was bandy, a game that has its roots in the Middle Ages. Just as for practically all other sports, the game of bandy achieved its modern form during the 19th century in England, more exactly in the Fen district on the East coast. From the Fen district the game was spread to London and from London to the Continent during the second half of the 19th century.[13]

British soldiers and immigrants to Canada and the United States brought their stick-and-ball games with them and played them on the ice and snow of winter.

To Roch Carrier, ice hockey is the synthesis of all of these precursors:

To while away their boredom and to stay in shape they [European colonial soldiers in North America] would play on the frozen rivers and lakes. The British [English] played bandy, the Scots played shinty and golf, the Irish, hurling, while the Dutch soldiers probably pursued ken jaegen. Curiosity led some to try lacrosse. Each group learned the game from the others. The most daring ventured to play on skates. All these contributions nourished a game that was evolving. Hockey was invented by all these people, all these cultures, all these individuals. Hockey is the conclusion of all these beginnings.[14]

In 1825, John Franklin wrote "The game of hockey played on the ice was the morning sport" on Great Bear Lake near the town of Délı̨nę during one of his Arctic expeditions.[citation needed] A mid-1830s watercolour portrays New Brunswick lieutenant-governor Archibald Campbell and his family with British soldiers on skates playing a stick-on-ice sport. Captain R.G.A. Levinge, a British Army officer in New Brunswick during Campbell's time, wrote about "hockey on ice" on Chippewa Creek (a tributary of the Niagara River) in 1839.[citation needed] In 1843 another British Army officer in Kingston, Ontario, wrote, "Began to skate this year, improved quickly and had great fun at hockey on the ice." An 1859 Boston Evening Gazette article referred to an early game of hockey on ice in Halifax that year.[15] An 1835 painting by John O'Toole depicts skaters with sticks and bung on a frozen stream in the American state of West Virginia, at that time still part of Virginia.[12]

In that same era, the Mi'kmaq, a First Nations people of the Canadian Maritimes, also had a stick-and-ball game. Canadian oral histories describe a traditional stick-and-ball game played by the Mi'kmaq, and Silas Tertius Rand (in his 1894 Legends of the Micmacs) describes a Mi'kmaq ball game known as tooadijik. Rand also describes a game played (probably after European contact) with hurleys, known as wolchamaadijik.[16][17] Oochamkunutk was the name used by the Mi'kmaq to describe their own stick and ball game which they played on the ice while alchamadyk was what the Mi'kmaq called the new the game of "hurley on ice" which was played by others around the province during the same period. Of particular note among influential Mi'kmaqs is Joe Cope ("Old Joe"), a Mi'kmaq elder known for his talent for carving what became one of the earliest types of ice hockey sticks used. Cope once stated, "Long before the pale faces strayed to this country, the Mi'kmaqs were playing two ball games, a field game and an ice game."[18] Sticks made by the Mi'kmaq were used by the British for their games.

In December of 2021, Mark Grant nominated the Mi'kmaq First Nation to the Hockey Hall of Fame for their development of an ice-adapted stick that was already in use in Halifax prior to the arrival of British colonists on June 21, 1749.[19] Grant notes that the Mi'kmaw have traditionally been described as mere craftsmen of hockey sticks, when in fact their contribution is much greater, as they introduced the ice hockey stick’s prototypical "flat thin blade." At the same time, he reached out to Canada's Governor General, whose office was involved in the introductions of the Stanley Cup and Campbell Cup. In his email to the Governor General, he noted that the Mi'kmaw's epic contributions to Canadian ice hockey have been known since 1872, yet no Canadian institution has formally recognized them for this well-known legacy. In 2023, Grant also sent group emails to Halifax's city council and the mayor's office, suggesting that they formally recognize the local Kjipuktuk Mi'kmaw and their partners, the settlers of Halifax and Dartmouth, for their immense contributions to Canadian and Nova Scotia culture through ice hockey.

Early 19th-century paintings depict shinny, an early form of hockey with no standard rules which was played in Nova Scotia.[20] Many of these early games absorbed the physical aggression of what the Onondaga called dehuntshigwa'es (lacrosse).[21] Shinny was played on the St. Lawrence River at Montreal and Quebec City, and in Kingston and Ottawa. The number of players was often large. To this day, shinny (derived from the Scottish game of shinty) is a popular Canadian[22] term for an informal type of hockey, either ice or street hockey.

Thomas Chandler Haliburton, in The Attache: Second Series (published in 1844) imagined a dialogue, between two of the novel's characters, which mentions playing "hurly on the long pond on the ice". This has been interpreted by some historians from Windsor, Nova Scotia as reminiscent of the days when the author was a student at King's College School in that town in 1810 and earlier.[15][16] Based on Haliburton's quote, claims were made that modern hockey was invented in Windsor, Nova Scotia, by King's College students and perhaps named after an individual ("Colonel Hockey's game").[23] Others claim that the origins of hockey come from games played in the area of Dartmouth and Halifax in Nova Scotia. However, several references have been found to hurling and shinty being played on the ice long before the earliest references from both Windsor and Dartmouth/Halifax,[24] and the word "hockey" was used to designate a stick-and-ball game at least as far back as 1773, as it was mentioned in the book Juvenile Sports and Pastimes, to Which Are Prefixed, Memoirs of the Author: Including a New Mode of Infant Education by Richard Johnson (Pseud. Master Michel Angelo), whose chapter XI was titled "New Improvements on the Game of Hockey".[25]

Initial development

[edit]

The city of Montreal, Quebec, Canada, became the center of the development of contemporary ice hockey, and is recognized as the birthplace of organized ice hockey.[26] On March 3, 1875, the first organized indoor game was played at Montreal's Victoria Skating Rink between two nine-player teams, including James Creighton and several McGill University students. Instead of a ball or bung, the game featured a "flat circular piece of wood"[27] (to keep it in the rink and to protect spectators). The goal posts were 8 feet (2.4 m) apart[27] (today's goals are 6 ft [1.8 m] wide). Some observers of the game at McGill made quick note of its surprisingly aggressive and violent nature.

Shins and heads were battered, benches smashed and the lady spectators fled in confusion.

— The Daily British Whig[28]

In 2023, Mark Grant challenged all suggestions that "organized" hockey began at the Victoria Skating Rink on March 3,1875. Grant pointed out that the actual birth of hockey in Montreal occurred two years before the Victoria Skating Rink match, while emphasizing that this is well known to informed historians. He refers to the actual birth of Montreal hockey "the least discussed most important episode in hockey history," adding that it solves many "unnecessary mysteries" of modern Ice Hockey's true origins, by confining earlier lineal historian to one location alone, Halifax.[29]

Grant says that the implications of the under considered Halifax-Montreal connection are paradigm altering, as the connection proves that 'the stick game' that became modern hockey was born in two nations at once, Canada and the Mi'kmaq First Nation, and no earlier than when those two parties first met on Halifax ice, no earlier than in the winter of 1749-50. The unambiguous nature of the Halifax-Montreal connection answers all suggestions that the origins of early ice hockey are a mystery, as is commonly believed.[30]

Grant also noted the rules of Halifax hockey were also described in 1943, twice, by Joe Cope, a Mi'kmaw player and Byron Weston, a former mayor of Dartmouth and a Nova Scotia Supreme Court judge. The most significant point about Cope's and Weston's testimonies, he says, is that they played with James Creighton who transferred the Halifax game to Montreal. "Cope and Weston have literally described 'the' version of Ice Hockey that Montreal inherited. Yet both have been squeezed out of the story of "organized" hockey for more than eighty years.[31]

Grant argues that much confusion has arisen as a result of the birth of Montreal being ignored in favor of what he calls the 1875 Victoria Skating Rink "mythologies." For example, it is often said or inferred that the March 3, VSR match introduced even-sided teams and goals. In his 1943 letter Joe Cope described their goals as "forts" and confirmed that he and Weston played a ten-man game.[32]

Weston said prohibited high sticking while requiring the puck, a flat block of wood, to remain on ice. (Grant says this was likely because the British stick games all involved raised sticks: Irish hurling (or rickets), Scottish shinty and English 'grass' hockey. Known for more than eighty years now, Weston'd description very clearly falsifies the often repeated claim that a wooden puck was first introduced at the March 3rd 1875 match in Montreal.[33] Other claims that rely on the VSR myths are easily corrected, if and when Halifax is considered. William Gill, for example, noted that the rubber puck was already in use in Halifax around 1872. Nor is it clear if "organized indoor" ice hockey was introduced in Montreal, as per the March 3, 1875 claim. Also lost to the general public, is the fact the Halifax Skating Rink opened a full twelve years earlier, in January of 1863. In 2023, Grant noted about a quarter to a third of the Halifax newspapers have been examined that pertain to the crucial 1863-to-1873 "pre Montreal" era. As such, it is far too early to even suggest that the Victoria Skating Rink was indeed the birthplace of indoor hockey.

In 1876, games played in Montreal were "conducted under the 'Hockey Association' rules";[34] the Hockey Association was England's field hockey organization. In 1877, The Gazette (Montreal) published a list of seven rules, six of which were largely based on six of the Hockey Association's twelve rules, with only minor differences (even the word "ball" was kept); the one added rule explained how disputes should be settled.[35] The McGill University Hockey Club, the first ice hockey club, was founded in 1877[36] (followed by the Quebec Hockey Club in 1878 and the Montreal Victorias in 1881).[37] In 1880, the number of players per side was reduced from nine to seven.[4]

The number of teams grew, enough to hold the first "world championship" of ice hockey at Montreal's annual Winter Carnival in 1883. The McGill team won the tournament and was awarded the Carnival Cup.[38] The game was divided into thirty-minute halves. The positions were now named: left and right wing, centre, rover, point and cover-point, and goaltender. In 1886, the teams competing at the Winter Carnival organized the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada (AHAC), and played a season comprising "challenges" to the existing champion.[39]

In 2024, Mark Grant argued that "world-class" hockey was introduced twenty years before Montreal's first Winter Carnival. This happened in Halifax around 1863, through the pairing of Canada's and Dartmouth revolutionary Acme skate and the Halifax-Kjipuktuk Mi'kmaw's flat thin-bladed stick. These superior technologies allowed hockey on ice to evolve rapidly, but only in Halifax. He notes that this occurred during a decade when players in other communities thought that 'hockey' on ice could be used with "any" kind of skate and stick, as per today's definition of what he calls "non-lineal" ice hockey.

Grant says that the spread of Montreal hockey was largely as series of technological demonstrations based on Halifax's superior skates and sticks. By the time of the first Winter Carnival, the most experienced players in Montreal had acquired the same level of experience that the best players in Halifax had already acquired by 1872 or 1873 - when James Creighton introduced Halifax hockey to Montreal. He argued that "world-class" hockey was introduced in Halifax starting in 1863, through the pairing of the Mi'kmaq stick and Dartmouth's Acme skate. Grant envisions a technological takeover of frontier Canada, where Halifax's prototypical gear spread by mass imitation, first by settlers and then at the commercial level, across Canada and then into the United States and Europe. Elsewhere he said, paraphrase: everywhere the Acme skate went, it skated cirles around the competition, while the Mi'kmaq stick had their competitors turned into 19th-century presto logs. One of Grant's main theses is that there is simply no way to understand Montreal ice hockey's rise without considering Halifax's earlier contributions, rather than ignoring it altogether, which has become the common practise. From the time of Montreal's introduction in 1872-73, to the Montreal game's 1893 conquest of the Stanley Cup and the professional game soon afterward, the rise and standardization of early modern ice hockey was a Halifax-Montreal game from start to finish. He says that while Montreal grabbed all of the glory, Halifax worked behind the scenes, feeding Canada's insatiable demand for its local technologies. [40] [41]

In Europe, it was previously believed that in 1885 the Oxford University Ice Hockey Club was formed to play the first Ice Hockey Varsity Match against traditional rival Cambridge in St. Moritz, Switzerland; however, this is now considered to have been a game of bandy.[42][43] A similar claim which turned out to be accurate is that the oldest rivalry in ice hockey history is between Queen's University at Kingston and Royal Military College of Kingston, Ontario, with the first known match taking place in 1886.[44]

In 1888, the Governor General of Canada, The Lord Stanley of Preston, first attended the Montreal Winter Carnival tournament and was impressed with the game. His sons and his daughter, Isobel Stanley, were hockey enthusiasts. In 1892, realizing that there was no recognition for the best team in Canada (although a number of leagues had championship trophies), he purchased a silver bowl for use as a trophy. The Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup (which later became known as the Stanley Cup) was first awarded in 1893 to the Montreal Hockey Club, champions of the AHAC; it continues to be awarded annually to the National Hockey League's championship team.[45] Stanley's son Arthur helped organize the Ontario Hockey Association, and Stanley's daughter Isobel was one of the first women to play ice hockey.

By 1893, there were almost a hundred teams in Montreal alone; in addition, there were leagues throughout Canada. Winnipeg hockey players used cricket pads to better protect the goaltender's legs; they also introduced the "scoop" shot, or what is now known as the wrist shot. William Fairbrother, from Ontario, Canada, is credited with inventing the ice hockey net in the 1890s.[46] Goal nets became a standard feature of the Canadian Amateur Hockey League in 1900. Left and right defence began to replace the point and cover-point positions in the OHA in 1906.[47]

American financier Malcolm Greene Chace is credited with being the father of hockey in the United States.[48] In 1892, Chace put together a team of men from Yale, Brown, and Harvard, and toured across Canada as captain of this team.[48] The first collegiate hockey match in the United States was played between Yale and Johns Hopkins in Baltimore in 1893.[49] In 1896, the first ice hockey league in the US was formed. The US Amateur Hockey League was founded in New York City, shortly after the opening of the artificial-ice St. Nicholas Rink.

By 1898 the following leagues had already formed: the Amateur Hockey League of New York, the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada, and the Ontario Hockey Association. The 1898 Spalding Athletic Library book includes rules and results for each league.[50]

Stanley's five sons were instrumental in bringing ice hockey to Europe, defeating a court team (which included the future Edward VII and George V) at Buckingham Palace in 1895.[51] By 1903, a five-team league had been founded. The Ligue Internationale de Hockey sur Glace was founded in 1908 to govern international competition, and the first European championship was won by Great Britain in 1910. The sport grew further in Europe in the 1920s, after ice hockey became an Olympic sport. Many bandy players switched to hockey to be able to compete in the Olympics.[52][53] In the mid-20th century, the Ligue became the International Ice Hockey Federation.[54]

As the popularity of ice hockey as a spectator sport grew, earlier rinks were replaced by larger rinks. Most of the early indoor ice rinks have been demolished; Montreal's Victoria Rink, built in 1862, was demolished in 1925.[55] Many older rinks succumbed to fire, such as Denman Arena, Dey's Arena, Quebec Skating Rink and Montreal Arena, a hazard of the buildings' wood construction. The Stannus Street Rink in Windsor, Nova Scotia (built in 1897) may be the oldest still in existence; however, it is no longer used for hockey. The Aberdeen Pavilion (built in 1898) in Ottawa was used for hockey in 1904 and is the oldest existing facility that has hosted Stanley Cup games.

The oldest indoor ice hockey arena still in use today for hockey is Boston's Matthews Arena, which was built in 1910. It has been modified extensively several times in its history and is used today by Northeastern University for hockey and other sports. It was the original home rink of the Boston Bruins professional team,[56] itself the oldest United States-based team in the NHL, starting play in the league in what was then called Boston Arena on December 1, 1924. Princeton University's Hobey Baker Memorial Rink was built in 1923 and is the second-oldest indoor hockey arena still in use and in Division I hockey behind Matthews Arena, but Princeton has the distinction of being the school that has played in its current rink the longest.[57] Madison Square Garden in New York City, built in 1968, is the oldest continuously-operating arena in the NHL.[58]

Professional era

[edit]

While scattered incidents of players taking pay to play hockey occurred as early as the 1890s,[59][60] those found to have done so were banned from playing in the amateur leagues which dominated the sport. By 1902, the Western Pennsylvania Hockey League (WPHL) was the first to employ professionals. The league joined with teams in Michigan and Ontario to form the first fully professional league—the International Professional Hockey League (IPHL)—in 1904. The WPHL and IPHL hired players from Canada; in response, Canadian leagues began to pay players (who played with amateurs). The IPHL, cut off from its largest source of players, disbanded in 1907. By then, several professional hockey leagues were operating in Canada (with leagues in Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec).

In 1910, the National Hockey Association (NHA) was formed in Montreal. The NHA further refined the rules: dropping the rover position, dividing the game into three 20-minute periods and introducing minor and major penalties. After re-organizing as the National Hockey League in 1917, the league expanded into the United States, starting with the Boston Bruins in 1924.

Professional hockey leagues developed later in Europe, but amateur leagues leading to national championships were in place. One of the first was the Swiss National League A, founded in 1916. Today, professional leagues have been introduced in most countries of Europe. Top European leagues include the Kontinental Hockey League, the Czech Extraliga, the Finnish SM-liiga and the Swedish Hockey League.

References

[edit]- ^ https://hockey-stars.ca/

- ^ https://hockey-stars.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/the-four-stars-of-early-ice-hockey-the-final-edition-february-11-2025-mark-grant-of-hockey-stars.ca_.pdf

- ^ https://www.abc27.com/business/press-releases/ein-presswire/717398595/81-year-old-article-solves-major-mysteries-about-ice-hockeys-origins/

- ^ a b Gidén, Carl; Houda, Patrick; Martel, Jean-Patrice (2014). On the Origin of Hockey.

- ^ Guinness World Records 2015. Guinness World Records. 2014. p. 218. ISBN 9781908843821. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Rymer, Thomas (1740). Foedera, conventiones, literae, et cujuscumque generis acta publica, inter reges Angliae, et alios quosvis imperatores, reges, pontifices ab anno 1101. Book 3, part 2, p. 79. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ Scott, Sir James Sibbald David (1868). The British Army: Its Origin, Progress, and Equipment. Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Company. p. 86. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ Joyce, Patrick Weston (1910). English As We Speak It in Ireland.

- ^ Latham, Richard C. "Polo". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ a b "History of Hockey". England Hockey. Archived from the original on May 9, 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ Gidén, Carl; Houda, Patrick (2010). "Stick and Ball Game Timeline" (PDF). Society for International Hockey Research. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2011.

- ^ a b "Hockey researchers rag the puck back to 1796 for earliest-known portrait of a player". Canada.com. May 17, 2012. Archived from the original on July 11, 2014. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- ^ Hansen, Kenth (May 1996). "The Birth of Swedish Ice Hockey – Antwerp 1920" (PDF). Citius, Altius, Fortius. 4 (2). International Society of Olympic Historians: 5–27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ^ Roch Carrier, "Hockey: Canada's Game", in Vancouver 2010 Official Souvenir Program, pg 42.

- ^ a b Vaughan, Garth (1999). "Quotes Prove Ice Hockey's Origin". Birthplace of Hockey. Archived from the original on August 6, 2001. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Dalhousie University (2000). Thomas Raddall Selected Correspondence: An Electronic Edition Archived August 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. From Thomas Raddall to Douglas M. Fisher, January 25, 1954. MS-2-202 41.14.

- ^ Thomas Raddall (25 January 1954). "Thomas Raddall Selected Correspondence: An Electronic Edition". library.dal.ca. Dalhousie University. Archived from the original on 2003-08-28. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ Garth Vaughan (1999). "Mi'kmaq Story Tellers: Nova Scotia Mi'kmaq Story Tellers". birthplaceofhockey.com. The Birthplace of Hockey. Archived from the original on November 20, 2022. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ https://hockey-stars.ca/hockey-hall-of-fame-nomination-essay-for-mikmaq-first-nation-2021/

- ^ "Provincial Sport Act: An Act to Declare Ice Hockey to be the Provincial Sport of Nova Scotia". Nova Scotia Legislature. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ Vennum, Thomas Jr. "The History of Lacrosse". USLacrosse.org. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ "About Shinny USA". Shinny USA. Archived from the original on August 19, 2011. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ Vaughan, Garth (1996). The Puck Starts Here: The Origin of Canada's Great Winter Game, Ice Hockey. Fredericton, NB, Canada: Goose Lane Editions. p. 23. ISBN 0864922124.

- ^ Gidén, Carl; Houda, Patrick (2016). "The Birthplace or Origin of Hockey". Society for International Hockey Research. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ Gidén, Carl; Houda, Patrick; Martel, Jean-Patrice (2014). On the Origin of Hockey. Hockey Origin Publishing. ISBN 9780993799808.

- ^ "IIHF to recognize Montreal's Victoria Rink as birthplace of hockey". IIHF. July 2, 2002. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- ^ a b "Victoria Rink". The Gazette. Montreal, Quebec. March 3, 1875.

- ^ "Ice hockey | History, Rules, Equipment, Players, & Facts". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on November 3, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ https://hockey-stars.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/henry-joseph-birth-montreal-ice-hockey-nov-27-1943-hockey-stars.ca_.png

- ^ https://hockey-stars.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/the-four-stars-of-early-ice-hockey-timeline-mark-grant-2024-1.png

- ^ https://hockey-stars.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/the-joe-cope-byron-weston-james-creighton-connection.png

- ^ https://hockey-stars.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/joe-cope-10-man-hockey-weston.jpg

- ^ https://hockey-stars.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/halifax-herald-westons-and-creightons-rules-mar-26-1943.pdf

- ^ "Hockey on the ice". The Gazette. Montreal, Quebec. February 7, 1876.

- ^ Fyffe, Iain (2014). On His Own Side of the Puck. pp. 50–55.

- ^ Zukerman, Earl (March 17, 2005). "McGill's contribution to the origins of ice hockey". Archived from the original on October 4, 2006. Retrieved October 11, 2006.

- ^ Farrell, Arthur (1899). Hockey: Canada's Royal Winter Game (PDF). Corneil. p. 27.

- ^ The trophy for this tournament is on display at the McCord Stewart Museum in Montreal. A picture of this trophy can be seen at McCord. "Carnival Cup". McCord Museum. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ "Sports and Pastimes, hockey, Formation of a Dominion Hockey Association". The Gazette. Montreal, Quebec. December 9, 1889. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ https://hockey-stars.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/essay-the-history-of-early-ice-hockey-mark-grant.pdf

- ^ https://hockey-stars.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/the-four-stars-of-early-ice-hockey-the-final-edition-february-11-2025-mark-grant-of-hockey-stars.ca_.pdf

- ^ Talbot, Michael (March 5, 2001). "On Frozen Ponds". Maclean's. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016.

- ^ Cambridge Evening News, "Sporting Heritage is Found", July 26, 2003.

- ^ "Carr-Harris Cup: Queen's vs. RMC Hockey". Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ Podnieks, Andrew; Hockey Hall of Fame (2004). Lord Stanley's Cup. Triumph Books. ISBN 1-55168-261-3.

- ^ Buckingham, Shane. "Lincoln touted as birthplace of the hockey net". St. Catharines Standard. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ Selke, Frank (1962). Behind the Cheering. Toronto, Ontario: McClelland and Stewart Ltd. p. 21.

- ^ a b "Malcolm G. Chace, 80, Industrial Leader, Dies", The Providence Sunday Journal, vol. LXXL, no. 3, Providence, Rhode Island, p. 24, July 17, 1955

- ^ "Position as Malcolm G. Chace Hockey Coach Inaugurated at Yale's Ingalls Rink in Honor of U.S. Hockey Founder" (Press release). Yale University. March 12, 1998. Archived from the original on November 1, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ US Archive, Spalding Athletic Library 1898 Ice Hockey and Ice Polo. [1] Retrieved January 8, 2021

- ^ "Murky Beginnings: The Establishment of the Oxford University Ice Hockey Club ca. 1885". Archived from the original on March 20, 2002. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ Converse, Eric (May 17, 2013). "Bandy: The Other Ice Hockey". The Hockey Writers. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ E.g. in the Netherlands, see Janmaat, Arnout (March 7, 2013). "120 jaar bandygeschiedenis in Nederland (1891–2011)" (PDF) (in Dutch). p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ^ International Ice Hockey Federation. "History of Ice Hockey". Archived from the original on July 19, 2006. Retrieved October 11, 2006.

- ^ "Victoria Skating Rink Property Sold". The Gazette. Montreal. September 5, 1925. p. 4.

- ^ "Northeastern University Athletics Official Website". Gonu.com. Archived from the original on January 2, 2010. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ^ Klein, Christopher (4 January 2010). "100 years on ice: What the puck?". ESPN.com. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ^ "Key Dates in The Madison Square Garden Company History". The Madison Square Garden Company. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ "Playing Hockey Here Is A Serious Offense...Bert Morrison Hauled Over the Coals in Montreal for Participating in Western Pennsylvania League Games-Hearing Is In Progress". The Pittsburgh Press. November 10, 1902. p. 12.

The London club alleged that [Bert] Morrison was an amateur under suspension by the O.H.A. when he played [against the London club in a game on November 8, 1902]: also that he received money directly or indirectly for playing hockey [in 1901] in Pittsburg (sic) and competed with and against [Harry] Peel and [goaltender] Hern, who have been professionalized by the O.H.A.

- ^ "Professional Hockey". The Ottawa Journal. February 8, 1898. p. 6.

The athletes in the city who are under the ban of professionalism think that they could organize a hockey team that would beat anything in the city in a practice game.