Hispanics and Latinos in Alaska

The 2020 Census reported that there were 49,824 Hispanics and Latinos in Alaska, 26,438 of whom lived in Anchorage, Alaska. The census also reported that 7.7% of Alaska's total population is of Hispanic or Latino origin.[1] In the late 18th century, the first known Hispanics and Latinos who came to Alaska were Spanish explorers. They traveled up to present day Valdez but didn't settle due to conflicts with England and the outcomes of the Nootka Conventions.[2] Since the purchase of Alaska in 1867, many Hispanics and Latinos moved to Alaska to work in mines, canneries, and on construction projects like the Trans-Alaska Pipeline.[3] These and other jobs drew individuals and families to Alaska and allowed many Hispanics and Latinos to contribute to the development of a unique culture.

History

[edit]

Early Spanish exploration in Alaska

[edit]The Spanish expeditions to the Pacific Northwest started in 1774 and lasted until 1794. The objectives of the expeditions were to search for Fonte's passage, a waterway to the Atlantic Ocean from the Pacific Ocean, and to find the Russians who were thought to be living in the area. Both would increase opportunities for economic growth and trade.[4]

The first expedition was led by Juan José Pérez Hernández, who turned back at present day Haida Gwaii due to sickness and lack of supplies. This expedition failed to reach Cape Muzon, the lowest point in Alaska (latitude of 54°40' N) or other waters in Southeast Alaska.[5]

One of the first Latinos to sail into Alaskan waters and to land on Alaska soil was Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra. Son of Tomás de la Bodega y de las Llanas, a Spanish-born deputy of the Spanish consulate in Cuzco, Juan was born in Peru.[6] He led two expeditions up the Northwest coast in 1775 and 1779. The furthest Bodega traveled up the coast was to 58° N, past what is now present day Sitka. Here he lost sight of land and had little hope of continuing before winter set in. He discovered no Russian settlements or Northwest passage.[4][7]

Other Spanish explorers led expeditions into Alaskan waters clear up to Valdez (61° 7' N).[2] During the Nootka Crisis (1789-1795), British and Spanish leaders sought control and sovereignty over what is now known as Vancouver Island and the surrounding areas. This conflict continued until the end of the Third Nootka Convention in 1794. British and Spanish explorers and traders decided to mutually abandon the ownership of Nootka Sound and only use it as a temporary but shared open port between both parties.[8] Shortly after, the Spanish completely withdrew from Alaska and the Nootka port. This allowed the British to expand their economic interests in the Pacific Northwest with little Spanish interference.[4][2]

Impact of Spanish exploration in Alaska

[edit]As a result of Spanish exploration in the Pacific Northwest, many names of Alaskan towns and cities have connections to the early Spanish influence and explorers.

Valdez was named after the Spanish naval officer Antonio Valdés. But as the Spanish explorers left and miners moved in, it became known as Copper City, due to the rich copper deposits in nearby mountains.[9] The name Copper City became less common after the post office changed its name to Valdez. Soon after, the town itself was renamed Valdez. Forty-five miles to the southeast of Valdez lies Cordova. The name Cordova was inspired by the bay that was formerly called Puerto Cordova, now called Orca Bay. Both Puerto Cordova and Valdez were named by Salvador Fidalgo, who explored this region in 1790.[10]

Much further south, close to Ketchikan, Alaska, is another testament of the Spanish northwestern coastal exploration, Revillagigedo Island. Captain George Vancouver named it after the viceroy of New Spain (1789-1794), Juan Vicente de Güemes, 2nd Count of Revilla Gigedo.[11] Many other geographical features have been named by Spanish explorers but have been changed or translated by Russian or North American immigrants over time.[2]

Early immigration and settlement of Hispanics and Latinos in Alaska

[edit]

Early Latino presence in Alaska

[edit]The Alaska Territory was bought by the United States on March 30, 1867, from Russia. The purchase was negotiated by Secretary of State William H. Seward.[13] It allowed thousands of people to explore and harvest the natural resources found there.

Mexicans were some of the first Latinos to permanently settle in Alaska worked in more labor intensive jobs.[14][15]

On 17 February 1931, The Daily Alaska Empire in Juneau, Alaska published a response to the claim that 5,000 "Mexicans in Alaska are held as slaves." This claim was denied by Territorial Governor George Alexander Parks.[16] Two days later, on 19 February 1931, a longer response was published in the same newspaper saying that Mexican slavery is "pure bunkum" and that "Nothing could be further from the truth." The newspaper goes on to say that "There are less than 500 Mexicans resident in Alaska. They came here because they could obtain profitable employment and remained from preference, very largely through a liking of conditions and the fact that they can earn here a better return for their labor than at home or in other lands."[12] This original newspaper publishing these false claims along with the newspapers that echoed across the American continent helped spread the idea that Mexicans were in Alaska.[17][18]

Latinos in Alaska post 1970

[edit]

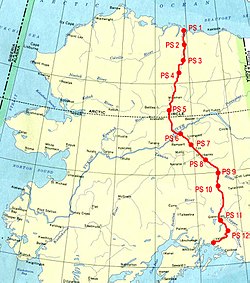

The discovery of oil in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska increased the number of Hispanics and Latinos in Alaska through the building of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. While the pipeline was being constructed from April 1974 to June 1977, more than 28,000 people worked on the 800-mile-long pipeline at its peak in construction in 1975.[19][20][21] High-paying jobs like the Trans-Alaska Pipeline attracted many immigrants and minorities seeking a better life.[3] One 1978 Alaskan newspaper told the story of Gume and Edmy Pena who came to Alaska because of the pipeline construction. While he was denied several jobs, moving to Alaska led Gume Pena to work for an oil company in Prudhoe Bay.

The Pena Family was originally from Zitácuaro, Michoacán, Mexico, and lived in Chicago for eight years before coming to Alaska.[22] Their story highlights the fact that for many Hispanics and Latinos, living in another part of United States for a time and then moving to Alaska was very common.[23]

Acuitzences in Alaska

[edit]Sara V. Komarnisky, a postdoctoral fellow in history at the University of Alberta, Edmonton has researched Mexicans in Alaska through the experiences of people from Acuitzio del Canje, Michoacán, Mexico (Acuitzences) and their migration to Anchorage, Alaska. In 2018, she published a book titled, Mexicans in Alaska: An Ethnography of Mobility, Place, and Transnational Life. Her book "examines how Acuitzences are living, working, and imagining their futures across North America" and analyzes the lives and experiences of three generations of migrants.[24]

Her work has been built upon her own previous research and the research of Raymond E. Wiest, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Manitoba, Canada.[25] Wiest's research highlights four reasons why the Acuitzences came to Alaska:

- The Acuitzences are not an indigenous community; they are a mestizo community, creating more opportunities over those who are indigenous.[26]

- Acuitzences who immigrated to Alaska were well-connected and economically stable in their hometown allowing them more social flexibility to be able to move to Alaska.

- “Acuitzio has long had an unusually high number of people with immigrant visas or ‘green cards.'" This makes it easier to overcome the legal obstacles of immigration.[27]

- “[There is] generational depth of migration to Alaska from Acuitzio,” meaning, that Acuitzences have gained entry because of their parents or grandparents.[28]

Legal impact of Hispanics and Latinos in Alaska

[edit]For those Hispanic or Latino immigrants (including the Acuitzences) in Alaska or the other states, the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 granted amnesty for those who entered the United States illegally before January 1, 1982 and applied for this protection.[23][29]

In addition, a change to a Mexican nationality law in 1998 allowed Mexicans to have dual citizenship. This legislation allowed Mexicans to gain citizenship of the United States and have protected rights in two countries.[30] Both of these legal changes made it easier for Mexicans to move between Alaska and Mexico.

People from other Latin and South American countries have benefited from other similar laws in Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua to name a few.[citation needed]

Demographics

[edit]The Demographics of Alaska are influenced by people with origins from all over the world.

The first major attempt to number the Hispanics in the United States took place with the 1970 Census. This census was completed by the individual person who answered a series of questions. These questions didn't work as hoped and the numbers were much different from previous estimations. The Federal Government didn't report each state's Hispanic estimates as the numbers weren't accurate.[31]

The 1980 Census clarified the questions and counted 14.6 million Hispanics.[31] The 1980 census in which it reported that 9,057 Hispanics and Latinos lived in Alaska.[32] The 2020 Census reported that there were 49,824 Hispanics and Latinos in Alaska. After 40 years, the number of Hispanics and Latinos increased 5.5%. This increase was evident through the immigration and births of many Hispanics and Latinos. In the 2020 U.S. Census, 7.7% of those living in Alaska were of Hispanic or Latino origin (of any race).[1]

The table below shows the reported numbers of Hispanics and Latinos in Alaska as a whole and in Anchorage, Alaska compared with the total population of the 1970 to 2020 U.S. Federal Censuses.

| Census Population Year | Total Alaska Population | Total Hispanics & Latinos in Alaska | Total Population in Anchorage | Hispanics & Latinos in Anchorage | Hispanics & Latinos outside Anchorage (Calculated) |

| 1970 Census[33] | 300,382 | Not reported for individual states | 124,542 | Not reported for individual cities | --- |

| 1980 Census[32] | 401,801 | 9,057 | 174,431 | Not reported | --- |

| 1990 Census[34] | 550,043 | 17,803 | 226,338 | 9,258 | 8,545 |

| 2000 Census[35] | 626,932 | 25,852 | 260,283 | 14,799 | 11,053 |

| 2010 Census[36] | 710,231 | 39,249 | 291,826 | 22,061 | 17,188 |

| 2020 Census[1] | 733,391 | 49,824 | 291,247 | 26,438 | 23,386 |

Cultural impact of Hispanics and Latinos in Anchorage, Alaska

[edit]More than half of all Hispanics and Latinos in Alaska live in Anchorage.[1]

Food

[edit]In 1977, Adan and Cecilia Galindo bought a tortilla factory after working there for five years. This factory, Taco Loco has sold "corn and flour tortillas, taco shells, and corn chips" for years.[37]

A PBS short documentary titled Sabor Ártico: Latinos En Alaska was created to showcase how Latinos in Alaska adapt and change to meet their cultural needs. One important cultural need is food. Alaska is so far away from many fresh ingredients that Latinos could get in easily in their ancestral counties. Because of the distance and cost of shipping, Latinos have adapted to eating more local Alaskan food while preserving elements of their ancestral homes and using what ingredients do get shipped to Alaska.[38]

Some Hispanic stores and restaurants in Anchorage, Alaska include:

- Salsas Oaxaqueñas: a Mexican restaurant that specializes in food and flavors originating from Oaxaca, Mexico. It opened in July 2024.[39]

- Ay Que Rico: a Puerto Rican food truck that opened in July 2024.[40]

- La Michoacana The Last Frontier: an ice cream shop that sells paletas, a frozen treat similar to that of a popsicle but made with fresh fruit.[41]

- Dominican Groceries: an authentic store for Latin American and Caribbean products.[42]

- Mexican Lindo Coffee Shop and Mini Market: a restaurant, store, and bakery that sells both American and Latin American dishes and ingredients.[43]

Religion

[edit]The Roman Catholic Our Lady of Guadalupe Cathedral is a prominent Cathedral in Anchorage, Alaska. The original parish was built in 1976 under the direction of Monseigneur John A. Lunney. The church was rebuilt in 2005 and serves as a spiritual, cultural, and community center for local Catholics and visitors.[44]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Alaska 2020, U.S. Census Bureau". data.census.gov. Retrieved 2025-03-28.

- ^ a b c d Overmyer-Velázquez, Mark, ed. (2008-10-30). Latino America: A State-by-State Encyclopedia. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 13–23. ISBN 978-1-57356-980-4.

- ^ a b García Castro, Ismael; Dayra L., Velázquez Verdugo (2013). "Mexico in its Newest Frontier: Mexican Immigrants in Anchorage (Alaska): Migratory Networks and Social Capital" (PDF). Mexico and the World. 18 (1).

- ^ a b c Bodega y Cuadra, Juan de la; Tovell, Freeman; Inglis, Robin; Engstrand, Iris Wilson (2012). Voyage to the Northwest Coast of America, 1792: Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra and the Nootka Sound controversy. Northwest historical series. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-87062-408-7.

- ^ Rodríguez-Sala, María Luisa (2006). De San Blas hasta la Alta California: los viajes y diarios de Juan Joseph Pérez Hernández (in Spanish). UNAM. ISBN 978-970-32-3474-5.

- ^ "BODEGA Y QUADRA (Cuadra), JUAN FRANCISCO DE LA". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved 2025-04-06.

- ^ Tovell, Freeman M. (2009-01-01). At the Far Reaches of Empire: The Life of Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-5836-6.

- ^ Calvo, Carlos (1862). Recueil complet des traités, conventions, capitulations, armistices et autres actes diplomatiques de tous les états de l'Amérique latine compris entre le golfe du Mexique et le cap de Horn, depuis l'année 1493 jusqu'à nos jours: précédé d'un mémoire sur l'état actuel de l'Amérique, de tableaux statistiques, d'un dictionnaire diplomatique, avec une notice historique sur chaque traité important (in Spanish). A. Durand.

- ^ "National Park Service: Golden Places: The History of Alaska-Yukon Mining (Preface: An Overview)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2025-04-06.

- ^ Phillips, James W. (2016-05-01). Alaska-Yukon Place Names. Epicenter Press. ISBN 978-1-941890-03-5.

- ^ Orth, Donald J. (1967). Dictionary of Alaska Place Names. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ a b "Mexican Slaves?". The Daily Alaska Empire. Juneau, Alaska, United States Of America. February 19, 1931. p. 4. Retrieved 2025-03-28.

- ^ Golder, Frank A. (1920). "The Purchase of Alaska". The American Historical Review. 25 (3): 411–425. doi:10.2307/1836879. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 1836879.

- ^ "The Death Of Agus-tine Browning Reported". Nogales Daily Morning Oasis. Nogales, Arizona, United States Of America. June 29, 1920. p. 1. Retrieved 2025-03-28.

- ^ ""The Local Field," Dec 15, 1915, page 3 - Douglas Island News". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2025-04-07.

- ^ "Says Mexicans In Alaska Are Held As Slaves". The Daily Alaska Empire. Juneau, Alaska, United States Of America. February 17, 1931. p. 1. Retrieved 2025-03-28.

- ^ "Soviets Are Given Blame, Report Mexicans Are Held Slaves in Alaska Re-sults in Charge". Lincoln (Nebraska) Journal Star. 24 February 1931. p. 1. Retrieved 2025-04-07.

- ^ "Conditions of Virtual Slaver, Claimed to Exist Concerning 5,000 Mexicans in Alaska". The Standard (St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada). 17 February 1931. p. 1. Retrieved 2025-04-07.

- ^ a b "Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS)". ConocoPhillips Alaska. Retrieved 2025-04-08.

- ^ Wells, Bruce (2024-06-16). "Trans-Alaska Pipeline History". American Oil & Gas Historical Society. Retrieved 2025-04-09.

- ^ Brusso, Barry C. (2018-04-11). "The 40-Year-Old Trans-Alaska Oil Pipeline [History]". IEEE Industry Applications Magazine. 24 (3): 8–76. doi:10.1109/MIAS.2018.2798019. ISSN 1558-0598.

- ^ Brennan, Marnie (17 July 1978). "Alaska Provides Realization of Mexican Family's Dreams". Anchorage (Alaska) Times. p. 27. Retrieved 2025-04-07.

- ^ a b Komarnisky, Sara V. (2012). "Reconnecting Alaska: Mexican Movements and the Last Frontier". Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics. 6 (1): 107–122.

- ^ "Mexicans in Alaska - Nebraska Press". University of Nebraska Press. Retrieved 2025-04-08.

- ^ "Faculty of Arts | University of Manitoba - Anthropology - Faculty and staff". Faculty of Arts | University of Manitoba. Retrieved 2025-04-08.

- ^ Wolf, Eric R. (1956). "Aspects of Group Relations in a Complex Society: Mexico". American Anthropologist. 58 (6): 1065–1078. doi:10.1525/aa.1956.58.6.02a00070. ISSN 0002-7294. JSTOR 666294.

- ^ Wiest, Raymond E. (1973). "Wage-Labor Migration and the Household in a Mexican Town". Journal of Anthropological Research. 29 (3): 180–209. doi:10.1086/jar.29.3.3629935. ISSN 0091-7710.

- ^ West, Raymond (2009). "Impressions of Transnational Mexican Life in Anchorage, Alaska: Acuitzences in the Far North" (PDF). Alaska Journal of Anthropology. 7 (1): 21–40.

- ^ Sen. Simpson, Alan K. [R-WY (1986-11-06). "S.1200 - 99th Congress (1985-1986): Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986". www.congress.gov. Retrieved 2025-04-08.

- ^ Exteriores, Secretaría de Relaciones. "Double Nationality". gob.mx (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-04-08.

- ^ a b Cohn, D’Vera (2010-03-03). "Census History: Counting Hispanics". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2025-04-08.

- ^ a b "Alaska 1980, Detailed Population Characteristics" (PDF). live.laborstats.alaska.gov. Retrieved 2025-03-28.

- ^ "Alaska 1970, Characteristics of the Population" (PDF). live.laborstats.alaska.gov. Retrieved 2025-03-28.

- ^ "Alaska 1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics" (PDF). census.gov. Retrieved 2025-03-28.

- ^ "Alaska: 2000, Summary Population and Housing Characteristics" (PDF). census.gov. Retrieved 2025-03-28.

- ^ "Alaska 2010, Summary Population and Housing Characteristics" (PDF). census.gov. Retrieved 2025-03-28.

- ^ Pounds, Nancy. "BUSINESS PROFILE: Taco Loco Products Inc." Alaska Journal of Commerce; Anchorage Vol. 26, Iss. 2, (Jan 13, 2002): 7.

- ^ VOCES | Sabor Ártico: Latinos En Alaska. Retrieved 2025-03-29 – via www.pbs.org.

- ^ "Salsa Oaxaqueña Mexican Restaurant – "Authentic Oaxacan Flavors, Freshly Crafted in the Heart of Anchorage."". Retrieved 2025-03-29.

- ^ "'Cooking is my passion'; new Kenai food truck serves Puerto Rican specialties". KDLL Public Radio for the Central Kenai Peninsula. 2024-07-25. Retrieved 2025-03-29.

- ^ "'Taste of home': New Latino- and Hispanic- owned restaurants serve up culture alongside cuisine". Alaska Public Media. 2024-08-30. Retrieved 2025-03-29.

- ^ "About Us – Dominican Groceries". Retrieved 2025-03-29.

- ^ "Restaurant review: With the spirit of an Anchorage mainstay, Mexico Lindo is serving up diner classics". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved 2025-03-29.

- ^ Guadalupe, Cathedral of Our Lady of. "PARISH HISTORY". olgak.org. Retrieved 2025-04-08.