Greek constitutional crisis of 1985

The Greek constitutional crisis of 1985 was the first constitutional dispute of the newly formed Third Hellenic Republic after the fall of the Greek Junta in 1974. It was initiated as a political gamble of Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou by suddenly declaring that he would not support the re-election of Constantine Karamanlis for a second term as President of the Republic. Papandreou also proposed constitutional amendments designed to further increase the power of his position by reducing the presidential powers, which were acting as checks and balances against the powerful executive branch.

Papandreou instead backed Supreme Court justice Christos Sartzetakis, who was popular with left-leaning voters for his investigation of the politically motivated murder of Grigoris Lambrakis in 1963.[1] Sartzetakis was elected president by the Hellenic Parliament in a tense and confrontational atmosphere due to constitutionally questionable procedures initiated by Papandreou.[2][3] The opposition, New Democracy led by Constantine Mitsotakis and Karamanlis' former party, deemed the vote illegal, with Mitsotakis threatening to remove Sartzetakis from the presidency if they won the upcoming elections, intensifying the constitutional crisis.[4] The confrontation dominated and polarized the election campaigns. However, Sartzetakis' election helped Papandreou and his socialist PASOK party to secure the 1985 Greek parliamentary election despite Papandreou's failure to address Greece's worsening economy. After the elections, all political parties accepted Sartzetakis as president, ending the constitutional crisis, and the constitutional amendments took effect in 1986. These amendments transformed the liberal democracy of Greece based on the constitution of 1975 into a 'populist democracy' with a majoritarian parliamentary system and a prime minister acting as a "parliamentary autocrat."[5][6]

Soon after the constitutional amendments took effect, Papandreou's premiership was engulfed by corruption scandals, with the Koskotas scandal standing out as the most significant. With no constitutional restraints, Papandreou abused his position to prevent the Koskotas case from advancing in the courts,[7] and his patronage reached new extremes as he promised to deplete the state's coffers to his loyal supporters.[8][9] After losing the 1989 elections, a collaborative government between conservative New Democracy and radical left Synaspismos parties, despite their ideological opposition and having fought against each other in the civil war, indicted Papandreou and four of his ministers, as well as breaking state's monopoly on the mass media and partially dismantling the state's surveillance capabilities, to prevent any future omnipotent prime minister from exploiting them for political advantage.[10][11] Since then, constitutional scholars have suggested partially reversing the removal of presidential powers to mitigate the negative effects of majoritarian politics while avoiding potential conflicts between the president and prime minister.[12]

Brief history of Constitutional crises in Greece

[edit]Kingdom versus republic

[edit]

Much of the history of modern Greece since its independence in 1821 from the Ottoman Empire has been turbulent. Upon the foundation of the First Hellenic Republic, the Greek political institutions and economy were underdeveloped and heavily indebted due to the liberation wars.[13] The lack of political conscience among the Greeks[i] led to friction between the local prominent families and the first Prime Minister Ioannis Kapodistrias, leading to his assassination.[14] The extensive borrowing made Greece subject to creditors, i.e., the European Great Powers, which imposed a foreign royal family[ii] as head of the Greek state, having absolute power.[15] This created tension between the Greek people, who sought more inclusive political participation to improve their living conditions, and the elites led by the king, who sought to please the foreign creditors and preserve their positions by actively intervening in political life. The tension eventually led to the military to intervene in politics; this lasted in the next century when Greece had eight military coups since World War I.[16] In early military movements, the military succeeded in securing a constitution from the king and a wide range of reforms, as in the case of 3 September 1843 Revolution and the Goudi coup in 1909, respectively.[17] From the Goudi coup, Eleftherios Venizelos became a prime minister with great popular appeal, modernized Greece, and greatly expanded the Greek territory in the Balkan Wars and World War I.[18] However, his policies brought him into conflict with King Constantine I regarding the entry of Greece in World War I with the Allies.[19] The disagreement between the two men resulted in the National Schism, dividing in half the society and the military, and the eventual expulsion of the king. The creation of the Second Hellenic Republic based on the Constitution of 1927 was, however, short-lived (1924–1935), and the king returned.[20] Later military movements tended to be in favor of the king, as happened with 4th of August Regime in 1936, led by General Ioannis Metaxas.[21]

Post World War II (1946–1952)

[edit]The Axis occupation in World War II and immediate 1944-49 civil war between the Communist-led uprising against the establishment led by the King, inflicted economic devastation and deepened cleavages in society.[22] After the lifting of martial law (1947–1950), post-civil-war governments were politically weak and heavily depended on the external patronage of the United States (Marshall Plan), and their primary focus was to contain communism amid Cold War.[23] The political dialogue of the following decades revolved around how power would shift from the Right (victors of the civil war) to the Center. However, the politicians delayed due to division on how to approach the necessary social reconciliation with the vanquished in the civil war, many of whom were either captured or exiled.[24] Another thorny issue was the control of the military by the elected government, i.e., politicians, instead of the king.[25]

Conservative rule (1952–1963)

[edit]The Constitution of 1952 was based on the Constitution of 1911, but it was effectively a new constitution since it violated the revision clause of the Constitution of 1911.[26] It established a parliamentary monarchy with the king as head of state and the army, based on the principle of the separation of powers.[26] However, the king maintained considerable powers, such as dissolving the government and parliament and calling new elections. Moreover, article 31[27] stated that the king hires and fires ministers (Greek: Ο βασιλεύς διορίζει και παύει τους υπουργούς αυτού). This created confusion as the prime minister was chosen by popular election, but the elected prime minister could not select the government's ministers without the king's approval. Two prime ministers in the 1950s had raised the question as to who governs the state, the king or the prime minister, echoing the disagreements between Venizelos and Constantine I during the National Schism.[28]

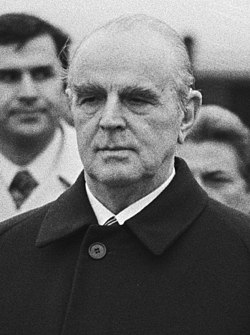

From 1955 to 1963, Greece was under the governorship of Constantine Karamanlis, who was widely acknowledged for bringing political and economic stability to Greece.[29] Karamanlis wanted to revise the Constitution of 1952 to reduce the king's prerogatives,[30] but failed to gain sufficient political capital to overcome the king's resistance. In the early 1960s, there was a growing awareness that the repressive measures taken due to civil war and its aftermath were no longer needed. This became clear with the death of a left-wing member of parliament (MP) Grigoris Lambrakis, where several high state officials were found to be involved either in the assassination or in its cover-up.[30] While no one, even from the severest of his left-wing critics, blamed Karamanlis for the incident, he resigned and self-exiled to France.[31]

Rise of Center-Left and friction with the king

[edit]Georgios Papandreou and his political party, Center Union, having a moderate reformist platform, gained considerable traction and rose to power in elections of 1963 and later in elections of 1964.[29][32] He advocated for the liberalization of Greek society, which was rapidly urbanizing, resulting in large salary increases for police, judges, and teachers. Papandreou's government also released all the political prisoners as a first step towards healing wounds from the civil war.[33] However, seeds of resentment towards Papandreou from the military grew as they were excluded from salary increases.[34] He also made a faint attempt to gain control of the military, which alarmed many officers without weakening them.[35][36] The latter created friction with the King Constantine II, who wanted to remain in command of the army and not the elected government.[33] In the meantime, the son of Georgios Papandreou, Andreas Papandreou, who had joined Greek politics after 23 years in the United States as a prominent academic,[37] was campaigning by having fierce anti-monarchy and anti-American rhetoric, destabilizing the fragile political equilibrium.[38][39] Andreas Papandreou's militant and uncompromising stance made him a target of conspiratorial accusations from ultra-rightists who feared that following any new elections, which the nearly 80-year-old Georgios Papandreou would likely win, his son would be the actual focus of power in the party.[40] These incidents caused a dispute between Georgios Papandreou and King Constantine II, leading to the resignation of the former.[41]

For the next twenty-two months, there was no elected government, and hundreds of demonstrations took place, with many being injured and killed in clashes with the police.[42] The king, potentially[iii] acting within his constitutional rights but politically dubious approach,[41] tried to bring members of the Center Union party to his side and form a government, leading to Apostasia of 1965.[43] He temporarily succeeded in getting 45 members, including Constantine Mitsotakis, to his side, who later were called 'apostates' by the side supporting Papandreous.[42][44] To end the political deadlock, Georgios Papandreou attempted a more moderate approach with the king, but Andreas Papandreou publicly rejected his father's effort and attacked the whole establishment, attracting the support of 41 members of the Center Union in an effort designed to gain the party's leadership and preventing any compromise.[38] The prolonged political instability between the politicians and the king in finding a solution led a group of Colonels to intervene and rule Greece for seven years. The junta regime expelled prominent political figures, including Andreas Papandreou, Constantine Mitsotakis, and the king. Nearly universally, the political world blamed Andreas Papandreou, even his father disowned him,[iv] as the person primarily responsible for the fall of Greek democracy.[39][45] In exile, Papandreou was a pariah, cut off from democratic and political forces working for the restoration of democracy in Greece. Moreover, he developed and spread to the public an anti-American conspiratorial[v] narrative of past events in which he was a victim of larger forces.[46] After the junta's fall due to its inability to handle the Turkish invasion of Cyprus,[47] the dominant political figure, Constantine Karamanlis, returned to restore democratic institutions in Greece.[48]

Restoration of democracy and Constitution of 1975

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Politics of Greece |

|---|

|

With the return of civilian rule under Karamanlis, the new government, acting under extraordinary circumstances, issued a "Constituting Act" which voided the junta's Constitution of 1973.[49] Pending a referendum on a new constitution, the 1952 constitution was temporarily restored, "except for the articles dealing with the form of the State"; the last phrase referred to whether the monarchy would be restored.[49] In the meantime, the functions of the king were to be discharged by the incumbent President Phaedon Gizikis, who was appointed by the junta's regime as a nominal figurehead.[50]

In November of 1974 Greek parliamentary election, Karamanlis received 56% of the vote and a mandate to set the foundations of the new state. In the December 1974 Greek republic referendum,[vi] 76% of voters chose a parliamentary republic with a president as head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces,[51] effectively voiding 150 years of tradition of monarchical rule.[52] This led to the foundation of the Third Hellenic Republic with the new Constitution of 1975, which reinforced the executive branch's power, represented by the prime minister, while the president would act as the head of state with sufficient reserve powers, the right to call elections, appoint a government, dissolve Parliament, and call referendums on important national questions. Moreover, the president could veto any legislation that did not reflect the popular will that could only be overcome with three fifth parliamentary majority.[51][53] The presidential powers, which overall exceeded those of the monarch under the 1952 Constitution, were drawn inspiration from the recent Gaullism reforms in the France where Karamanlis spent time (1963–1974).[51] Despite vocal resistance from the leftist parties, which wanted a purely parliamentary system with a ceremonial president, Karamanlis insisted that these powers would act as checks and balances to prevent an omnipotent prime minister who could accumulate executive and legislative powers without any restraint.[54] Parliament adopted the new constitution and it was promulgated on 11 June 1975. Andreas Papandreou, along with the communists, boycotted the promulgation of the constitution, and he publicly described it as "totalitarian," advocating instead for a "socialist" constitution without further elaborating on what he meant.[55][51]

From 1975 until 1980, Karamanlis and his close associate Konstantinos Tsatsos governed Greece as prime minister and president of Greece, respectively. The healing of the wounds caused by the civil war was pressing since the junta had only exacerbated them. Towards this direction, Karamanlis had legitimized the Communist Party (KKE),[vii][56] which was outlawed since November 1947 during the civil war, re-ratified the European Convention on Human Rights,[57] and opened the borders to exiled Greeks who had fled the junta and civil war to return home, including Melina Merkouri, Mikis Theodorakis, and Cornelius Castoriadis.[58] Approximately 25,000 returned after passing strict security screening from 1974 to 1981.[59] However, Karamanlis' governments maintained the post-civil war state's anticommunist stance, i.e., it was challenging to get a civil service job as a communist. Minister of Interior Konstantinos Stefanopoulos explained the conservative viewpoint as "Greeks would never forgive those who had taken up arms against the Nation."[60]

In the meantime, Papandreou and his newly formed political party (PASOK) rose in popularity due to the rising pressure from the 1973 and 1979 oil crisis on the Greek economy and Papandreou's radical rhetoric, mostly anti-American and anti-EEC. In 1980, after Karamanlis secured the entry of Greece into European Economic Community (EEC), he became president, handing over the premiership to Georgios Rallis, which created a power vacuum that contributed to Andreas Papandreou winning the 1981 Greek parliamentary election and becoming prime minister.[61] In the eyes of Greece's allies, Karamanlis, as president, would act as a restraining factor on radical departures in foreign and domestic affairs if Papandreou realized his campaign promises.[62][63] Papandreou took further steps in achieving social reconciliation by allowing the return of another potential 22,000 returnees by dropping the security screening; the most notable was Markos Vafiadis at age 77.[59] In 1985, Papandreou introduced a law for civil servants dismissed for political reasons to restore their pension.[59] All formal Civil War commemorations were abolished, including ceremonies commemorating Dekemvriana.[64] The first law recognizing the Greek Resistance was passed in 1949, which excluded left-leaning partisan groups that fought against the Greek State in the Greek Civil War. On 20 September 1982, Papandreou's government passed a law that abolished this exception, allowing EAM/ELAS members the war veteran status and pension rights.[59] However, Papandreou, unlike Karamanlis's inclusive approach, instrumentalized the painful and divided past by regularly invoking the memories of the civil war ("right the wrongs of the past") and "revenge of the losers [of the Civil War]" (Greek: "η ρεβάνς των ηττημένων") to maintain the support of the left-leaning faithful by demonstrating to them that PASOK remained true to its campaign promises and left-wing roots.[59][65] For Papandreou, polarization was necessary to distract his supporters from his mishandling of the chronic stagflation state of the Greek economy despite the influx of economic aid from EEC.[66] Nevertheless, the cohabitation of the two men in the 1981–1985 period was successful since Papandreou governed in a more pragmatic approach compared to his radical polarizing rhetoric, by reversing many of his campaign promises.[67]

Constitutional crisis

[edit]First stage

[edit]On 6 March 1985, New Democracy announced that they would support Karamanlis' second Presidency term, while on the same day, the KKE party declared that they would put forward their candidate. The press anticipated that Papandreou would also support Karamanlis,[68] since he had assured Karamanlis his support in person.[69] However, Papandreou changed his mind at the last moment, siding with the left wing of PASOK, which did not want Karamanlis, and instead backed Christos Sartzetakis (a Supreme Court of Greece judge known for his principled handling of the 1963 murder of left-wing deputy Grigoris Lambrakis and viewed favorably by the left, and a protagonist in Costas Gavras' 1969 movie "Z" based on the novel of Vassilis Vassilikos).[68][69] The announcement occurred at the Central Committee of PASOK on 9 March.[68] This move surprised some of Papanderou's ministers, much of his party's rank-and-file, and even Sartzetakis himself, who was not consulted in advance.[68] Later on, it was revealed that the supposedly spontaneous change of mind was to camouflage Papandreou's long-held constitutional designs since Sartzetakis not only knew about it well in advance but also that there had been two other judicial figures who rejected Papandreou's offer.[70] At the same time, Papandreou announced plans for a constitutional reform, which rekindled the debate about the form of the republic and further polarized the political environment by damaging the consensus between the two dominant political parties, PASOK and New Democracy, that existed between 1981 and 1985.[71]

Papandreou also argued that it would be illogical for Karamanlis to preside over any constitutional reform since much of the constitution of 1974 was heavily influenced by Karamanlis himself.[55] Mitsotakis accused Papandreou of creating a constitutional crisis to remove Karamanlis from office to establish a totalitarian constitution.[72] Papandreou informed Karamanlis of his decision via his deputy, Antonios Livanis, as he could not bring himself to do so in person.[73] In response, Karamanlis resigned from the Presidency on 10 March 1985, two weeks before the termination of his term, and was replaced by PASOK's Speaker of the Hellenic Parliament, Ioannis Alevras, as acting president.[55]

Vote eligibility of the acting president

[edit]The opposition raised the issue of whether Alevras could participate in the parliamentary vote for his successor, requesting to be precluded from the presidential vote and his deputy rights while acting president.[74] Specifically, the Constitution of 1975 states that the president's office is incompatible with any other office (Article 30). Constitutional scholars supported this viewpoint.[74] Specifically, academic Nikolaos Saripolos believed that only the Constituent Assembly could determine whether Alevras could vote.[74] PASOK argued that there was no explicit provision in the constitution, so this issue should be resolved in the Parliament; an opinion from Grigorios Kasimatis and friend of Papandreou.[74] Ultimately, the PASOK-dominated parliament decided to allow it, with New Democracy deputies leaving the chamber.[75] PASOK deputy Agamemnon Koutsogiorgas later argued in Parliament that the issue raised by constitutional scholars on Alevras' ineligibility to vote due to Article 30 in the Constitution applies only to elected presidents and therefore does not apply to Alevras.[75]

Parliamentary votes for president & colored ballots

[edit]According to the Constitution of 1975, up to three rounds of a parliamentary vote were permitted for presidential candidates; the first two rounds required more than 200 votes out of 300 members of parliament, and in the third round, 180 votes out of 300.[76] If all three rounds failed, then new elections would be held. Papandreou could only rely upon approximately 164 MPs (he had expelled six PASOK MPs for criticizing him since 1981), 13 MPs from the KKE, and five independent MPs (about 182).[3] The first two rounds failed to elect Sartzetakis as president, which took place on 17 and 23 March. The elections were carried out in conditions of high political tension; at one point, a New Democracy deputy momentarily grabbed the ballot box.[3]

Like in the previous rounds, in the third round on 29 March, colored ballots (in blue color for Sartzetakis) and semi-transparent envelopes were used.[2][3][77] New Democracy chairman Mitsotakis accused Papandreou of violating constitutional principle of secret ballot (Article 32),[76] by forcing his deputies to cast their vote with colored ballots.[viii][3][78] However, Mitsotakis' concern was dismissed because PASOK controlled the majority in the Parliament.[3] Mitsotakis and Papandreou ended up having a verbal confrontation. Mitsotakis claimed Papandreou had no respect for the Parliament, and Papandreou responded, with Mitsotakis' role in the Apostasia in mind, that the latter was the last person entitled to speak about respect.[ix][3] Despite vigorous protests from the opposition, PASOK members used colored ballots under strict surveillance to spot potential defectors.[79][78] Outside the building of the Parliament, PASOK supporters were chanting.[79]

Sartzetakis was voted president with a decisive vote from Alevras since Papandreou's party suffered the defection of two MPs, who Papandreou accused of taking bribes from Mitsotakis' party.[79] Mitsotakis considered the vote illegal and claimed that if New Democracy won the elections, Sartzetakis would not be president by bringing the legality of the process to Council of State (Greek: Συμβούλιο Επικρατείας), further deepening the constitutional crisis.[4][78]

Foreign policy dimension

[edit]Foreign observers were worried that Papandreou unleashed a high-stakes gamble with potentially dire consequences for Greece and its allies. McDonald asserts that a victory for Mitsotakis in the upcoming elections would destabilize Greece over the presidency question.[80] On the other hand, an electoral weakened Papandreou might lead to a collaboration with the communist party to form a government, which according to John C. Loulis, a conservative Greek political analyst, stated that such a coalition "raised a potential danger to the balance of power in the Mediterranean" due to the possibility of communists shaping Greece's foreign policy and disrupting the communications in North Atlantic Treaty Organization.[81]

Constitutional proposals & debate

[edit]With Sartzetakis as president, Papandreou could formally submit the proposals for constitutional amendments by adding to the previous one the removal of a secret ballot for president.[82] In contrast with constitution violations raised in Sartzetakis's election,[83] PASOK's procedure in proposing constitutional amendments was under the constitution.[70] However, the surprising announcement of constitutional reform under already tense political conditions and the limited input from constitutional scholars on the nature of amendments increased the possibility of the crisis becoming widespread.[84] Papandreou's proposals were designed to ease future changes to the constitution in Article 110 to require amendments to be approved by a parliamentary majority in one rather than two successive parliaments and reducing the powers of the President.[85] While the former proposal was eventually abandoned due to its controversial nature,[85] Papandreou was determined to eliminate the presidential powers. His argument was the hypothetical case of an activist president, mimicking the tendency of kings of Greece to intervene in the political life since the creation of the modern Greek state.[86] PASOK minister Anastasios Peponis introduced the constitutional amendment package to the Parliament with the following argument:

Invoking the lack of use of some provisions, their lack of implementation is by no means an argument to keep them in the current constitution. The question is what is our guiding principle? When provisions directly or indirectly contradict the principle of popular sovereignty, we object to them. [...] We support that the president is neither directly appointed by nor elected by the people. We are not a presidential, we are a parliamentary democracy. It is not the president who resorts to the people, so that the people deliver a verdict by majority voting. It is the legitimate government. It is the political parties. If the president resorts to the people, then he inevitably either sides with one party against others or attempts to substitute himself for the parties and impose his own solution. Nevertheless, as soon as he attempts to substitute himself for the parties and impose his own solution, then he embarks upon the formation of his own decisions of governmental nature. Then the government, directly or indirectly, fully or partially, is abolished.[87]

Scholars considered such constitutional changes "unnecessary" since no president had utilized these powers in the course of the Third Hellenic Republic until the time Papandreou raised the issue.[88][86] Moreover, Anna Benaki-Psarouda, New Democracy's rapporteur, presented in the parliament the following argument against the proposed reforms:

And this is the achievement of the 1975 Constitution: A miraculous balance between the Parliament, the Government and the President of the Republic, namely these state organs which express popular sovereignty and always pose the risk of de facto usurping it. [...] It is also interesting to see where these competencies of the President of the Republic are transferred. They are removed from him, but where do they go? To popular sovereignty and the Parliament, as the parliamentary majority claims? Dear colleagues, all of them go to the government, either directly or indirectly through the parliamentary majority controlled by it. Because the parliament is now subjugated to the parliamentary majority through party discipline. [...] Dear colleagues, the conclusion from the amendments suggested by the government or the parliamentary majority is the following: Power is transferred completely to the government. Hence, we have every reason to be afraid and suspect and mistrust about the future of Greece. [...] I want to stress the following, so that we, the Greek people, understand well: that with the suggested amendments you turn government and government majority into superpowers.[89]

Psarouda-Benaki effectively argued that this type of majoritarianism would damage the quality of Greek democracy.[89] Scholars also noted that the proposed changes would make the prime minister the most powerful ("autocratic") position in the Greek state since there would not be any constitutional restraints.[5][6]

Election campaign of 1985

[edit]

Both parties continued their confrontations in the campaigns for the June 1985 parliamentary election, where the political polarization reached new heights. Mitsotakis declared, "In voting, the Greek people will also be voting for a president"[82] and also warned that there is a danger of sliding towards an authoritarian one-party state.[90] The president's office responded, "The president of the republic will remain the vigilant guardian of the constitution."[91] From PASOK, Agamemnon Koutsogiorgas described what was at stake not as "oranges and tomatoes but the confrontation between two worlds." [92] Papandreou followed this by characterizing the upcoming elections as a fight between light and darkness in his rallies, implying that PASOK represented the "forces of light" since its logo was a rising sun.[92] Papandreou further argued that every vote against PASOK was a vote for the return of the Right with the slogan "Vote PASOK to prevent a return of the right."[93] The communists, persecuted by the Right in the 1950s, protested against Papandreou's dwelling on the past, pointing out that the 1980s were not the same as the 1950s.[93] The Economist magazine described Greece as a "country divided," tearing itself apart and opening the wounds of civil war.[94] Just before the elections, Karamanlis broke his silence and urged the Greeks to be cautious with their vote (without explicitly advising who to vote), commenting that PASOK had brought "confusion and uncertainty."[95] However, Karamanlis' statement was not broadcast on TV and radio, which were controlled by the state and governing party, i.e., PASOK.[95]

In the event, PASOK was re-elected with 45.82% of the vote, losing approximately 2.3% from 1981, while New Democracy increased its share of the vote by 4.98% to 40.84%.[96] Papandreou's gamble worked to his benefit because he gained from far-left voting blocks covering the losses from the centrist voters, and appealed to socialist voters who rejected Karamanlis's perceived hindrance of PASOK's policies.[97][70] Papandreou had the upper hand over Mitsotakis in which he argued that a vote for Mitsotakis is a vote for a constitutional anomaly,[98] convincing a significant fraction of Greek voters.[70][98] Richard Clogg states that the large-scale rally by Mitsotakis on 2 June at Syntagma Square may have panicked communists to vote for PASOK;[99] the communist parties lost a significant share of the vote.[100]

Aftermath

[edit]After the election results, Mitsotakis accepted Sartzetakis as president and the head of the state.[101] Papandreou's constitutional proposals took effect in 1986.[102]

Papandreou began his second administration with a comfortable majority in parliament and increased powers based on the amended constitution. However, his premiership was soon mired in numerous financial and corruption scandals; Koskotas scandal was an extensive corruption and money-laundering operation threatening the PASOK government since it implicated many senior PASOK ministers and Papandreou.[103] At the same time, the Greek economy rapidly deteriorated as Papandreou, shaken by PASOK's waning popularity, reversed the austerity measures imposed by the European Economic Community (EEC) for a loan to save the Greek economy from bankruptcy.[100][9][104] Moreover, choices made in the early 1980s on repealing anti-terrorism legislation and controversial foreign policy decisions led to a significant rise in terrorist incidents in Greece.[105][106]

Despite the rising public frustration with the state of affairs, Papandreou abused his position to remain in power since there were no constitutional restraints. Notable actions include but are not limited to the following:

- Papandreou changed the electoral law shortly before the June 1989 general elections, a move designed to prevent New Democracy from scoring an absolute majority.[x][107][108][109]

- Bestowing public appointments to about 90,000 people to gain additional votes six months before the 1989 elections; [110] Synaspismos political party decried this as a "recruitment orgy."[111] Papandreou's blatant patronage, which had been burdening the economy throughout the 1980s,[112] reached the point of giving in one of his rallies a public command to the Minister of Finance Dimitris Tsovolas to "give it all [to them]" (Greek: Τσοβόλα δώσ'τα όλα) and "Tsovolas, empty the coffers [of the state]," and the crowd chanted these back.[8][9]

- During the judicial inquiries of the Koskotas scandal, it was revealed that Papandreou used the Junta's surveillance infrastructure (filing and wiretapping) against any Greek citizen who was not loyal to him.[104][113][114] In the list of "suspected terrorists" according to Papandreou included prominent politicians across the political spectrum, his ministers, publishers, policy chiefs, and even PASOK's governmental spokesman.[115]

- Judicial independence was damaged when Papandreou passed a law via emergency procedures despite massive backlash from lawyers, judges, and clerks, to prevent the judicial investigation of the Koskotas scandal from advancing to Athens Appeals Court.[7]

Papandreou lost the June 1989 election, mainly due to the Koskotas scandal.[116] Mitsotakis' party got 43%, but it was insufficient to form a government; Papandreou's last-minute change of the electoral vote law required a party to win 50% of the vote to govern alone. Papandreou hoped that while PASOK might come second in electoral votes, it could form a government with the support of the other leftist parties, but he was rejected.[117] Instead, the right-wing New Democracy collaborated with the radical left Synaspismos party, led by Charilaos Florakis, to form a government. The two parties, while belonging to opposite ideological camps (as well as having battled one another in the Greek Civil War), both sought a "catharsis," i.e., an investigation and trial of PASOK's corruption.[103][110][118] The new government indicted Papandreou and four of his ministers. Moreover, to avoid political exploitation from any future omnipotent prime minister, they dismantled some of the junta's surveillance infrastructure and granted the first private television broadcast license to publishers critical to PASOK as a counterbalance to state media.[10][11]

In the elections of April 1990, Mitsotakis received sufficient (by one seat above the threshold) support to form a government, and Papandreou became the opposition leader,[103] marking the end of PASOK's political dominance in its first era.[119]

Scholars examined Greek electoral preferences during the catharsis era and found that the Greek people perceive political corruption differently from other Western countries, placing greater importance on personality and charisma over morality.[120] One scholar noted, "This refusal to distinguish between party loyalty on the one hand, and political corruption and constitutional violence on the other, is another sad reflection of contemporary Greek life."[120]

Constitutional crisis evaluation and political consensus

[edit]Contemporary constitutional scholar Aristovoulos Manesis provided in 1989 a detailed assessment of the constitutional crisis as follows.[121] While the constitutional revision of 1985 did not lead to or be the result of a violent confrontation as it happened in the revisions of 1911 with the Goudi coup, in 1952 after the civil war, and in 1975 after the Junta, the commonality between all these constitutional revisions was that they were imposed by the political party in power without the participation or consent of the minority.[xi][122] He also argued that the manner in which the presidential election was announced and conducted and the nature of the constitutional amendments had the potential of political rupture, while the latter also decreased the Constitution's democratic character due to the concentration of power in the prime minister's position along with the emerging statist bureaucracies and technologies aimed at controlling the popular will.[xii][121] At the end of his criticism, he advocated for strengthening individual rights and institutions as a counterweight to the executive branch led by the prime minister.[123] Nikos Alivizatos, a constitutional scholar, considered the methods employed by PASOK to elect Sartzetakis in 1985 as "unacceptable," and while he did not blame the change in the presidency in 1985 as the source of "corruption and moral crisis" that became apparent in the following years, he acknowledged that the removal of constitutional restraints caused PASOK "to neglect the rules of the parliamentary game,"[124] and signaled that it "would not hesitate to overcome any obstacle in its aim to retain power."[125] In similar lines, Stathis Kalyvas, a political scientist, and Richard Clogg, a historian, note that while the actions by Papandreou did not directly threaten the democratic form of the Constitution, however, they undermined its long-term legitimacy.[78][101] Political scientist Dimitrios Katsoudas wrote that the constitutional revision was unnecessary and damaged the established legality of the Constitution[126] and opined that Papandreou had long-term constitutional designs to reinforce his government party against an impotent parliament.[88]

Takis Pappas, a political scientist, stated that PASOK's general strategy in the 1980s involved three methods state grabbing, institution bending, and political polarization.[127] For Pappas, the events surrounding the constitutional crisis, as described above, are placed in one of these methods. Specifically, the constitutional reform was part of state grabbing, while the presidential election was part of bending or even disregarding liberal institutions to the will of popular sovereignty[127] that gradually transformed Greece from a liberal democracy based on the Constitution of 1975 into a "populist democracy."[128] Political polarization became most prominent during elections through political mobilization, which was aided by the press and state-controlled television and radio, creating divisions in social life.[129]

Historians John Koliopoulos and Thanos Veremis suggested that the crisis was motivated by Papandreou's desire to divert the Greek electorate's attention away from the worsening state of the Greek economy (unemployment increased under PASOK from 2.7% in 1980 to 7.8% in 1985,[130] annual inflation of the order of 20%,[131] widening trade deficits).[132] According to a public opinion survey by Eurobarometer, the number of Greeks who believed that the economic situation worsened increased from 37.7% in 1983 to 70.2% in 1985, while those who believed that the economy improved fall from 31.5% to 12.8% in the same period.[133] Kevin Featherstone, political scientist, also considers that the motive behind Papandreou's actions was to divert public attention from economic policies.[134] While Papandreou contended that Karamanlis' removal was necessary for the constitutional revision, Manesis argued the reverse: the constitutional revision was a pretext to justify the removal of Karamanlis, which would remind left-leaning voters as the elections were approaching that PASOK remained faithful to its revolutionary left-wing origins.[135] Manesis also points to PASOK's lack of preparation for the constitutional revision, noting that frequent changes to the proposed amendments were made even days before their submission, which he sees as a clear sign of partisan politics.[136]

Greek constitutional reformers commonly include in their proposals the return of some prerogatives taken back to the president to reduce the negative effects arising from majoritarian politics, i.e., 'winner takes all,' while avoiding conflicts between the president and prime minister in the executive branch.[12] In a collaboration headed by former Finance Minister Stefanos Manos involving Alivizatos and others, it was proposed for the president to have the right to dissolve Parliament as a way to counterbalance the omnipotent prime minister.[137] However, the president's term would be six years long and non-renewable.[138]

In 1990, New Democracy, having a slim majority in the Parliament, elected Karamanlis as (second term) president after five rounds of votes with PASOK and Synaspismos supporting their candidates.[139] After this, there has been political consensus that the governing party should choose a candidate for president who is acceptable by the opposition; the exception to this trend was with Konstantinos Tasoulas in 2025.[140][141]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The integration of the liberated Greek people into the newly formed state was slow, leaving parts of rural Greece outside state control. Of particular concern was the activity of irregular troops, some of whom acted as bandits, e.g., livestock rustling, robbery, and kidnapping of foreigners for ransom;[142] the most notable incident was the Dilessi murders of 1870, which inspired the 1980 movie Alexander the Great by Theo Angelopoulos.

- ^

- ^ Scholars are cautious in taking sides regarding the constitutionality of the king's actions. Of those who take a side, there are two schools of thought: the strict and legal interpretation of the Constitution (the letter of the law) and the emphasis on the constitutional conventions and principles (the spirit of the law). In the former school of thought, the king acted within his constitutional rights, while in the latter, the king's actions violated the Constitution of 1952.[144]

- ^

- ^ There is a long-standing debate on whether the Johnson administration gave the green light for the 1967 coup in Greece.[146] Andreas Papandreou and his academic colleagues frequently accused the US administration of being responsible for the coup, and since then, Andreas Papandreou and other Greek elites sold this to the masses as part of nurturing anti-American sentiment, making it a widespread belief among Greeks.[147][148][149] Others are more skeptical due to the lack of "smoking gun" evidence. Louis Klarevas, based on the declassified documents of the US government and extensive literature review, concluded that there was no official action for the coup, however, additional evidence is required to determine any unofficial activities.[146]

- ^

- ^ The legitimation of the communist party had far-reaching implications.[151] In the following years, a whole range of institutions that were founded for the persecution of Communists that existed since the 1920s disappeared.[151] Police, along with vigilante groups and spies whom they had employed, could no longer threaten everyone's civil rights or stigmatize them on ideological grounds.[151]

- ^ According to constitutional scholar Aristovoulos Manesis, the constitutional principle of the secret ballot was violated in three different ways: by PASOK's use of colored ballots, by the opposition refusing to vote but being present, and by the last ballot of Alevras.[83]

- ^ While Andreas Papandreou and Constantine Mitsotakis started from the same political party, and both competed for the leadership of the Center Union,[152] Andreas had vilified Mitsotakis for Apostasia of 1965 (siding with the king and in the view of Andreas betraying his father) as a "traitor" and a "nightmare" effectively stigmatizing the life-long career of Mitsotakis in Greek politics.[153][154] In 1984, Mitsotakis became the New Democracy party leader because he was the only active politician (Karamanlis was President at the time) who could rival Andreas Papandreou.[153] From 1984 until 1990, the political conflict between Papandreou and Mitsotakis was both personal and polarized.[152] After winning the elections of 1990, Mitsotakis lacked the political capital and sufficient majority to implement his policies despite his long-term ministerial experience, resulting in Mitsotakis's tenure being short.[155]

- ^ While it is frequent in Greek history for the governing party to change the electoral law for its purposes, Papandreou's electoral law change in 1989 was unique as it personally benefited him to avoid an indictment for the Koskotas scandal and be sentenced to life in prison if convicted.[156]

- ^ Manesis also made the following distinctions in this comparison. While all political parties were invited and participated in the creation of the Constitution of 1975, in the end, due to the disagreement on the extent of presidential powers, the minority political parties (PASOK and the communist parties) did not vote,[157] leaving Karamanlis, as he said, "debating with absentees."[158] In this narrow sense, Manesis argues, the Constitution 1975 was imposed by a single political party but asserts that Karamanlis had a sufficiently strong mandate.[157] The constitutional revision in 1985, apart from dubious constitutional procedures in the presidential election that were necessary for the revision to take place, also features characteristics of single-party imposition since the objections of the minority, this time Karamanlis' former party (New Democracy), were sidelined.[157]

- ^ Samatas highlighted PASOK's use of the junta's military surveillance for political gains.[11] This was accompanied by populist rhetoric and patronage networks aimed at mobilizing and controlling the masses, ultimately safeguarding Andreas Papandreou's position both within the party and as prime minister.[11]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Featherstone & Papadimitriou 2015, p. 87.

- ^ a b Alivizatos 2011, pp. 530–531.

- ^ a b c d e f g Clogg 1985, p. 109.

- ^ a b Clogg 1985, pp. 110–111.

- ^ a b Katsoudas 1987, p. 28.

- ^ a b Featherstone 1990, p. 183.

- ^ a b Magalhaes, Guarnieri & Kaminis 2006, p. 185.

- ^ a b Pappas 2019, p. 247.

- ^ a b c Siani-Davies 2017, p. 35.

- ^ a b Papathanassopoulos 1990, p. 394.

- ^ a b c d Samatas 1993, p. 47.

- ^ a b Alivizatos 2020, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Kofas 2005, p. 97.

- ^ Clogg 2013, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, p. 34.

- ^ Liakos & Doumanis 2023, p. 259.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, pp. 36-37 & 66-67.

- ^ Clogg 2013, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Curtis 1995, pp. 44–54.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, pp. 101–103.

- ^ Clogg 2013, p. 115.

- ^ Clogg 2013, p. 142.

- ^ Kofas 2005, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Clogg 2013, pp. 142–144.

- ^ Close 2014, pp. 107–108.

- ^ a b Spyropoulos & Fortsakis 2017, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Greek Constitution 1952, p. 6.

- ^ Dervitsiotis 2019, p. 240.

- ^ a b Clogg 1975, p. 334.

- ^ a b Clogg 1975, pp. 334–335.

- ^ Clogg 1975, p. 335.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, p. 137.

- ^ a b Curtis 1995, p. 70.

- ^ Lagos 2021, p. 47.

- ^ Tsarouhas 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Mouzelis 1978, p. 126.

- ^ Clive 1985, p. 491.

- ^ a b Close 2014, p. 109.

- ^ a b c Featherstone & Papadimitriou 2015, p. 84.

- ^ Clogg 1996, p. 383.

- ^ a b Clogg 2013, pp. 158–159.

- ^ a b Close 2014, p. 108.

- ^ Close 2014, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Hatzivassiliou 2006, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Miller 2009, pp. 136 & 144.

- ^ Miller 2009, pp. 144–146.

- ^ Clogg 1996, p. 384.

- ^ Close 2014, p. 123.

- ^ a b Karamouzi 2015.

- ^ Liakos & Doumanis 2023, p. 306.

- ^ a b c d Clive 1985, p. 492.

- ^ Kaloudis 2000, p. 48.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, p. 155.

- ^ Grigoriadis 2017, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c Clogg 1985, p. 106.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, p. 186.

- ^ Spyropoulos & Fortsakis 2017, p. 55.

- ^ Liakos & Doumanis 2023, p. 307.

- ^ a b c d e Siani-Davies & Katsikas 2009, p. 569.

- ^ Fytili, Avgeridis & Kouki 2023, p. 14.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Nafpliotis 2018, p. 517.

- ^ Larrabee 1981, p. 164.

- ^ Fytili, Avgeridis & Kouki 2023, p. 15.

- ^ Liakos & Doumanis 2023, p. 310.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, p. 169.

- ^ Curtis 1995, p. 219.

- ^ a b c d Clogg 1985, p. 105.

- ^ a b Featherstone & Papadimitriou 2015, p. 86.

- ^ a b c d McDonald 1985, p. 134.

- ^ Grigoriadis 2017, p. 43.

- ^ Clogg 1985, p. 107.

- ^ Featherstone & Papadimitriou 2015, p. 114.

- ^ a b c d Clogg 1985, p. 108.

- ^ a b Clogg 1985, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b Greek Constitution 1975, p. 631.

- ^ Pantelis 2007, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d Kalyvas 1997, p. 97.

- ^ a b c Clogg 1985, pp. 109–110.

- ^ McDonald 1985, p. 133.

- ^ Washington Post May 1985.

- ^ a b Clogg 1985, p. 110.

- ^ a b Manesis 1989, p. 66.

- ^ Manesis 1989, p. 7.

- ^ a b Clogg 1987, pp. 104–105.

- ^ a b Alivizatos 1993, p. 66.

- ^ Grigoriadis 2017, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Katsoudas 1987, pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b Grigoriadis 2017, p. 44.

- ^ Clogg 2013, p. 194.

- ^ Clogg 1987, p. 115.

- ^ a b Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, p. 166.

- ^ a b Clogg 1987, p. 108.

- ^ Close 2004, p. 267.

- ^ a b Clogg 1985, p. 111.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Clogg 1985, pp. 111–112.

- ^ a b Clogg 1987, p. 116.

- ^ Clogg 1987, p. 113.

- ^ a b Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, p. 167.

- ^ a b Clogg 1985, p. 112.

- ^ Greek Constitution 1986.

- ^ a b c Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, p. 170.

- ^ a b Close 2014, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Stergiou 2021, pp. 166–169.

- ^ Kassimeris 1993, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Magone 2003, p. 172.

- ^ Gallant 2016, p. 293.

- ^ Clogg 2013, p. 196.

- ^ a b Close 2014, p. 159.

- ^ Featherstone 1990, p. 112.

- ^ Liakos & Doumanis 2023, pp. 316–317.

- ^ Koutsoukis 2006, p. 131.

- ^ Samatas 1993, pp. 44–47.

- ^ Samatas 1993, pp. 44 & 68.

- ^ Dobratz & Whitfield 1992, pp. 167–180.

- ^ Clive 1990, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Clogg 2013, p. 197.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, p. 171.

- ^ a b Dobratz & Whitfield 1992, p. 172.

- ^ a b Manesis 1989, pp. 6–102.

- ^ Manesis 1989, pp. 11-12 & 17-18.

- ^ Manesis 1989, pp. 100–102.

- ^ Alivizatos 1993, p. 68.

- ^ Alivizatos 2020, p. 112.

- ^ Katsoudas 1987, pp. 26 & 28.

- ^ a b Pappas 2014, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Pappas 2014, p. 36.

- ^ Pappas 2014, p. 29.

- ^ IMF, Greece's unemployment.

- ^ IMF, Greece's inflation rate.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, pp. 164–166.

- ^ Pappas 2014, p. 32.

- ^ Featherstone 1990b, p. 108.

- ^ Manesis 1989, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Manesis 1989, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Alivizatos et al. 2016, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Alivizatos et al. 2016, p. 25.

- ^ Proto Thema Jan. 2025.

- ^ Naftemporiki Jan. 2025.

- ^ in.gr Jan. 2025.

- ^ Pappas 2018, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, pp. 42–45.

- ^ Anastasiadis 1981, p. 139.

- ^ Papandreou 1971, pp. 24 & 312.

- ^ a b Klarevas 2006, pp. 471–508.

- ^ Michas 2002, p. 94.

- ^ Larrabee 1981, p. 160.

- ^ Miller 2009, p. 114.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, p. 154.

- ^ a b c Close 2014, p. 142.

- ^ a b Clogg 2013, p. 190.

- ^ a b Curtis 1995, p. 232.

- ^ Washington Post Mar. 1985.

- ^ Liakos & Doumanis 2023, p. 345.

- ^ New York Times Jan. 1992.

- ^ a b c Manesis 1989, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Koliopoulos & Veremis 2009, p. 160.

Sources

[edit]- Constitutions of Greece

- "Greek Constitution of 1952". Government Gazette (Greece) ΦΕΚ A 1/1952 (in Greek). National Printing Office.

- "Greek Constitution of 1975". Government Gazette (Greece) ΦΕΚ A 111/1975 (in Greek). National Printing Office.

- "Greek Constitution of 1986". Government Gazette (Greece) ΦΕΚ A 23/1986 (in Greek). National Printing Office.

- Proposed Constitutions for Greece

- Alivizatos, Nicos C.; Vourloumis, Panagis; Gerapetritis, Georgios; Ktistakis, Yannis [in German]; Manos, Stefanos; Spyropoulos, Philippos (2016). Ένα Καινούργιο Σύνταγμα για την Ελλάδα: Κείμενα Εργασείας [An Innovative Constitution for Greece: Working Papers] (PDF). Athens: Μεταίχνιο.

- Books

- Alivizatos, Nikos (2011). Το Σύνταγμα και οι εχθροί του στη νεοελληνική ιστορία 1800-2010 (in Greek). Athens: ΠΟΛΙΣ. ISBN 9789604353064.

- Manesis, Aristovoulos (1989). Η συνταγματική αναθεώρηση του 1986 [Constitutional resivion of 1986] (in Greek). Athens: Παρατηρητής. ISBN 9789602603543.

- Anastasiadis, George (1981). Ο διορισμός και η παύση των κυβερνήσεων στην Ελλάδα: από την "αρχή της δεδηλωμένης" στο Σύνταγμα του 1975 [The appointment and dismissal of governments in Greece: From the 'principle of declared confidence' to the 1975 Constitution] (in Greek). Athens: University Studio Press. ISBN 9780001208902.

- Carabott, Philip; Sfikas, Thanassis D., eds. (2004). The Greek Civil War: essays on a conflict of exceptionalism and silences. Surrey: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754641322.

- Close, David. "The road to reconciliation". In Carabott & Sfikas (2004), pp. 257-278.

- Clogg, Richard (1987). Parties and elections in Greece: the search for legitimacy. North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 0822307944.

- ——————, ed. (1993). Greece, 1981–89: The Populist Decade. London & New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781349230563.

- Alivizatos, Nikos C. "The Presidency, Parliament and the Courts in the 1980s". In Clogg (1993), pp. 65-77.

- —————— (2013). A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107656444.

- Close, David H. (2014). Greece since 1945: Politics, Economy and Society. London & New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317880011.

- Curtis, Glenn E. (1995). Greece, A Country Study. Maryland: Library of Congress. ISBN 1490436235.

- Dervitsiotis, Alkis (2019). Η έννοια της Κυβέρνησης (in Greek). Athens: P.N. Sakkoulas SA. ISBN 9789604208005.

- Featherstone, Kevin; Katsoudas, Dimitrios K., eds. (1987). Political change in Greece: Before and after the colonels. London & New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000992144.

- Katsoudas, Dimitrios K. "The Constitutional framework". In Featherstone & Katsoudas (1987), pp. 14-33.

- ——————; Papadimitriou, Dimitris (2015). Prime Ministers in Greece, The Paradox of Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198717171.

- Featherstone, Kevin; Sotiropoulos, Dimitri A., eds. (2020). The Oxford Handbook of Modern Greek Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198825104.

- Alivizatos, Nikos C. "Greek constitutionalism and patterns of government". In Featherstone & Sotiropoulos (2020), pp. 103-116.

- Gallant, Thomas W. (2016). Modern Greece: From the war of independence to the present. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781350014510.

- Garrard, James; Newell, John, eds. (2006). Scandals in past and contemporary politics. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719065514.

- Koutsoukis, Kleomenis S. "Political scandals and crisis management in Greece, 1821-2001". In Garrard & Newell (2006), pp. 123-136.

- Grigoriadis, Ioannis N., ed. (2017). Democratic transition and the rise of Populist Majoritarianism: Constitutional Reform in Greece and Turkey. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9783319575551.

- Grigoriadis, Ioannis N. "The Rising Tide of Populist Majoritarianism in Greece". In Grigoriadis (2017), pp. 41-52.

- Gunther, Richard; Diamandouros, Nikiforos; Sotiropoulos, Dimitri, eds. (2006). Democracy and the state in the new southern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191513961.

- Magalhaes, Pedro C.; Guarnieri, Carlo; Kaminis, Yorgos. "Democratic consolidation, judicial reform, and the judicialization of politics in Southern Europe". In Gunther, Diamandouros & Sotiropoulos (2006), pp. 138-196.

- Hatzivassiliou, Evanthis [in Greek] (2006). Greece and the Cold War Front Line State, 1952-1967. London & New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781134154883.

- Koliopoulos, John S.; Veremis, Thanos M. [in Greek] (2009). Modern Greece A History Since 1821. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781444314830.

- Kofas, Jon V. (2005). Independence from America: global integration and inequality. Burlington: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754645085.

- Lagos, Katerina; Othon, Anastasakis, eds. (2021). The Greek Military Dictatorship Revisiting a Troubled Past, 1967-1974. New York & London: Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781800731752.

- Lagos, Katerina. "The political and ideological origins of the Ethosotitios Epanastasis". In Lagos & Othon (2021), pp. 34-72.

- Liakos, Antonis [in Greek]; Doumanis, Nicholas (2023). The Edinburgh History of the Greeks, 20th and Early 21st Centuries: Global Perspectives. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1474410847.

- Magone, José (2003). The Politics of Southern Europe Integration Into the European Union. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313051678.

- Miller, James (2009). The United States and the Making of Modern Greece. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1469622163.

- Mouzelis, Nicos P. (1978). Modern Greece: facets of underdevelopment. London: The Macmillan Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0333226155.

- Pappas, Takis (2014). Populism and crisis politics in Greece (in Greek). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137410580.

- —————— (2019). Populism and liberal democracy: A comparative and theoretical analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192574893.

- Pantelis, Antonis (2007). Εγχειρίδιο Συνταγματικού Δικαίου [Constitutional Law handbook] (PDF) (in Greek). Livanis Publications.

- Papandreou, Andreas (1971). Democracy at Gunpoint. New York: Deutsch. ISBN 9780233963013.

- Pridham, Geoffrey, ed. (1990). Securing Democracy, Political Parties and Democratic Consolidation in Southern Europe. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415023269.

- Featherstone, Kevin. "Political Parties and democratic consolidation in Greece". In Pridham (1990), pp. 179–202.

- Siani-Davies, Peter (2017). Crisis in Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190911539.

- Spyropoulos, Philippos C.; Fortsakis, Theodore P. (2017). Constitutional Law in Greece. Netherlands: Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 9789041192448.

- Stergiou, Andreas (2021). Greece's Ostpolitik Dealing With the 'Devil'. Cham: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 9783030611293.

- Journal

- Clive, Nigel (1985). "The 1985 Greek Election and its Background". Government and Opposition. 20 (4): 488–503. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.1985.tb01100.x. JSTOR 44483257.

- —————— (1990). "The Dilemmas of Democracy in Greece". Government and Opposition. 25 (1): 115–122. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.1990.tb00750.x. JSTOR 44482490.

- Clogg, Richard (1975). "Karamanlis's cautious success: the background". Government and Opposition. 10 (3): 332–255. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.1975.tb00644.x. JSTOR 44483305.

- —————— (1985). "The 1985 Constitutional Crisis in Greece". The Journal of Modern Hellenism. 2 (1): 103–112.

- —————— (1996). "Andreas Papandreou – A political profile". Mediterranean Politics. 1 (3): 382–387. doi:10.1080/13629399608414596.

- Dobratz, Betty A.; Whitfield, Stefanie (1992). "Does Scandal Influence Voters' Party Preference? The Case of Greece during the Papandreou Era". European Sociological Review. 8 (2): 167–180. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a036630. JSTOR 522295.

- Featherstone, Kevin (1990b). "The 'party‐state' in Greece and the fall of Papandreou". West European Politics. 13 (1): 101–115. doi:10.1080/01402389008424782.

- Fytili, Magdalini; Avgeridis, Manos; Kouki, Eleni (2023). "Heroes or Outcasts? The Long Saga of the State's Recognition of the Greek Resistance (1944–2006)". Contemporary European History: 1–19. doi:10.1017/S0960777323000395.

- Kaloudis, George (2000). "Transitional democratic politics in Greece". International Journal on World Peace. 17 (1): 35–39. JSTOR 20753241.

- Kalyvas, Stathis N. (1997). "Polarization in Greek Politics: PASOK's First Four Years, 1981-1985". Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora. 23 (1): 83–104.

- Klarevas, Louis (2006). "Were the eagle and the phoenix birds of a feather? The United States and the Greek coup of 1967". Diplomatic History. 30 (3): 471–508. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.2006.00562.x. JSTOR 24915022.

- Karamouzi, Eirini (2015). "A strategy for Greece: Democratization and European integration, 1974-1975". Cahiers de la Méditerranée. 90 (90): 11–24. doi:10.4000/cdlm.7858.

- Kassimeris, George (1993). "The Greek state response to terrorism". Terrorism and Political Violence. 5 (4): 288–310. doi:10.1080/09546559308427230.

- Larrabee, F. Stephen (1981). "Dateline Athens: Greece for the Greeks". Foreign Policy. 45 (45): 158–174. doi:10.2307/1148318. JSTOR 1148318.

- McDonald, Robert (1985). "Greece after PASOK's Victory". The World Today. 41 (7): 133–136. JSTOR 40395748.

- Michas, Takis (2002). "America the despised". The National Interest. 67 (67): 94–102. JSTOR 42897404.

- Nafpliotis, Alexandros (2018). "From radicalism to pragmatism via Europe: PASOK's stance vis-à-vis the EEC, 1977-1981". Southeast European and Black Sea Studies. 18 (4): 509–528. doi:10.1080/14683857.2018.1519686.

- Papathanassopoulos, Stylianos (1990). "Broadcasting, politics and the state in Socialist Greece". Media, Culture & Society. 12 (3): 387–397. doi:10.1177/016344390012003007.

- Pappas, Nicholas C. (2018). "Brigands and brigadiers: the problem of banditry and the military in nineteenth-century Greece". Journal of History. 4 (3): 179–183. doi:10.30958/AJHIS.4-3-2. S2CID 186900394.

- Samatas, Minas (1993). "The Populist Phase of an Underdeveloped Surveillance Society: Political Surveillance in Post-Dictatorial Greece". Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora. 19 (1): 31–70.

- Siani-Davies, Peter; Katsikas, Stefanos (2009). "National reconciliation after civil war: The case of Greece". Journal of Peace Research. 46 (4): 559–575. doi:10.1177/0022343309334611. JSTOR 25654436.

- Tsarouhas, Dimitris (2005). "Explaining an activist military: Greece until 1975" (PDF). Southeast European Politics. 6 (1): 1–13.

- Newspapers & magazines

- Jonathan C. Randal (13 March 1985). "Greek Opposition Leader Gladdened by Papandreou's Shift". The Washington Post.

- Jonathan C. Randal (29 May 1985). "Leader of Greek Communist Party Assails Ruling Socialists, Opposition". The Washington Post.

- Marlise Simons (17 January 1992). "Greek Ex-Premier Not Guilty in Bank Scandal". The New York Times.

- "Μητσοτάκης: Μία εξαετή θητεία για τον Πρόεδρο της Δημοκρατίας – Η πρόταση ενόψει συνταγματικής αναθεώρησης". in.gr (in Greek). 15 January 2025.

- "Αδ. Γεωργιάδης για ΠτΔ: Όταν ο Ανδρέας Παπανδρέου πρότεινε τον Χρήστο Σαρτζετάκη, ήταν από άλλη παράταξη;". Νaftemporiki (in Greek). 16 January 2025.

- Μιχάλης Στούκας (19 January 2025). "Από τον Μιχαήλ Στασινόπουλο στον Κωνσταντίνο Τασούλα - Όλοι οι ένοικοι του Προεδρικού Μεγάρου". Proto Thema (in Greek).

- Web and other sources

- "Greece's unemployment (%)". International Monetary Fund.

- "Greece's inflation rate (%)". International Monetary Fund.

Additional reading

[edit]- Nikos Alivizatos (29 January 2025). "How powerful a president does our political system want?". Kathimerini.