Federally recognized tribe

| Federally recognized tribe | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Category | Political divisions |

| Location | United States |

| Number | 574 |

| Government | |

| Subdivisions | |

A federally recognized tribe is a Native American tribe recognized by the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs as holding a government-to-government relationship with the US federal government.[1] In the United States, the Native American tribe is a fundamental unit of sovereign tribal government. As the Department of the Interior explains, "federally recognized tribes are recognized as possessing certain inherent rights of self-government (i.e., tribal sovereignty)...."[1] The constitution grants to the U.S. Congress the right to interact with tribes.

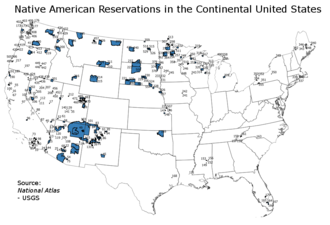

In the 1831 Supreme Court of the United States case Cherokee Nation v. Georgia Chief Justice of the United States John Marshall wrote that a Native American government is a "domestic dependent nation'" whose relationship to the United States is like that of a "ward to its guardian". The case was a landmark decision which led to the United States recognizing over 574 federally recognized tribal governments and 326 Indian reservations which are legally classified as domestic dependent nations with tribal sovereignty rights. The Supreme Court held in United States v. Sandoval[2] "that Congress may bring a community or body of people within range of this power by arbitrarily calling them an Indian tribe, but only that in respect of distinctly Indian communities the questions whether, to what extent, and for what time they shall be recognized and dealt with as dependent tribes" (at 46).[3] Federal tribal recognition grants to tribes the right to certain benefits, and is largely administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

While trying to determine which groups were eligible for federal recognition in the 1970s, government officials became aware of the need for consistent procedures. To illustrate, several federally unrecognized tribes encountered obstacles in bringing land claims; United States v. Washington (1974) was a court case that affirmed the fishing treaty rights of Washington tribes; and other tribes demanded that the U.S. government recognize aboriginal titles. All the above culminated in the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, which legitimized tribal entities by partially restoring Native American self-determination.

Native American sovereignty and the Constitution

[edit]The United States Constitution mentions Native American tribes three times:

- Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 states that "Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States ... excluding Indians not taxed."[4] According to Story's Commentaries on the U.S. Constitution, "There were Indians, also, in several, and probably in most, of the states at that period, who were not treated as citizens, and yet, who did not form a part of independent communities or tribes, exercising general sovereignty and powers of government within the boundaries of the states."

- Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution states that "Congress shall have the power to regulate Commerce with foreign nations and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes",[5] determining that Indian tribes were separate from the federal government, the states, and foreign nations;[6] and

- The Fourteenth Amendment, Section 2 amends the apportionment of representatives in Article I, Section 2 above.[7]

These constitutional provisions, and subsequent interpretations by the Supreme Court (see below), are today often summarized in three principles of U.S. Indian law:[8][9][10]

- Territorial sovereignty: Tribal authority on Indian land is organic and is not granted by the states in which Indian lands are located.

- Plenary power doctrine: Congress, and not the Executive Branch or Judicial Branch, has ultimate authority with regard to matters affecting the Indian tribes. Federal courts give greater deference to Congress on Indian matters than on other subjects.

- Trust relationship: The federal government has a "duty to protect" the tribes, implying (courts have found) the necessary legislative and executive authorities to effect that duty.[11]

History

[edit]Colonial and early U.S. history

[edit]From the beginning of the European colonization of the Americas, Europeans often removed Indigenous peoples from their homelands. The means varied, including treaties made under considerable duress, forceful ejection, violence, and in a few cases voluntary moves based on mutual agreement. The removal caused many problems such as tribes losing the means of livelihood by being restricted to a defined area, poor quality of land for agriculture, and hostility between tribes.[12]

Early English settlers in the Americas entered into treaties with Native American tribes as a method of legitimizing their conquests in the face of competing claims by the Spanish Empire and violent resistance from the tribes themselves.[13] Applying the term "treaty" to such unequal relationships may seem paradoxical from a modern perspective because in modern English, the word "treaty" usually connotes an agreement between two states of theoretically equal sovereignty, not an agreement between conquered people and a conqueror.[13] However, in premodern times, it was common for European princes to routinely enter into unequal treaties with lesser dependent powers.[13]

The first reservation was established by Easton Treaty with the colonial governments of New Jersey and Pennsylvania on August 29, 1758. Located in southern New Jersey, it was called Brotherton Indian Reservation[14] and also Edgepillock[15] or Edgepelick.[16] The area was 3,284 acres (13.29 km2).[15] Today it is called Indian Mills in Shamong Township.[15][16]

In 1764 the British government's Board of Trade proposed the "Plan for the Future Management of Indian Affairs".[17] Although never adopted formally, the plan established the British government's expectation that land would only be bought by colonial governments, not individuals, and that land would only be purchased at public meetings.[17] Additionally, this plan dictated that the Indians would be properly consulted when ascertaining and defining the boundaries of colonial settlement.[17]

The private contracts that once characterized the sale of Indian land to various individuals and groups—from farmers to towns—were replaced by treaties between sovereigns.[17] This protocol was adopted by the United States Government after the American Revolution.[17]

On March 11, 1824, U.S. Vice President John C. Calhoun founded the Office of Indian Affairs (now the Bureau of Indian Affairs) as a division of the United States Department of War (now the United States Department of Defense), to solve the land problem with 38 treaties with American Indian tribes.[18]

The Marshall Trilogy, 1823–1832

[edit]

The Marshall Trilogy is a set of three Supreme Court decisions in the early nineteenth century affirming the legal and political standing of Indian nations.

- Johnson v. McIntosh (1823), holding that private citizens could not purchase lands from Native Americans.

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), holding the Cherokee nation a "domestic dependent nation", with a relationship to the United States like that of a "ward to its guardian".

- Worcester v. Georgia (1832), which laid out the relationship between tribes and the state and federal governments, stating that the federal government was the sole authority to deal with Indian nations.[19]

Marshall’s phrasing "laid the groundwork for future protection of tribal sovereignty by Marshall and his immediate successors, but the characterization also created an opportunity for much later courts to discover limits to tribal sovereignty inherent in domestic dependent status. Marshall’s reference to tribes as 'wards' was to have an equally mixed history".[20]

Letters from the presidents of the United States on Indian reservations (1825–1837)

[edit]Indian Treaties, and Laws and Regulations Relating to Indian Affairs (1825) was a document signed by President Andrew Jackson[21] in which he states that "we have placed the land reserves in a better state for the benefit of society" with approval of Indigenous reservations before 1850.[22] The letter is signed by Isaac Shelby and Jackson. It discusses several regulations regarding the Native Americans and the approval of Indigenous segregation and the reservation system.

President Martin Van Buren negotiated a treaty with the Saginaw Chippewas in 1837 to build a lighthouse. The President of the United States of America was directly involved in the creation of new treaties regarding Indian Reservations before 1850. Van Buren stated that indigenous reservations are "all their reserves of land in the state of Michigan, on the principle of said reserves being sold at the public land offices for their benefit and the actual proceeds being paid to them."[23] The agreement dictated that the indigenous tribe sell their land to build a lighthouse.[23]

A treaty signed by John Forsyth, the Secretary of State on behalf of Van Buren, also dictates where indigenous peoples must live in terms of the reservation system in America between the Oneida People in 1838. This treaty allows the indigenous peoples five years on a specific reserve "the west shores of Saganaw bay".[24] The creation of reservations for indigenous people of America could be as little as a five-year approval before 1850. Article two of the treaty claims "the reserves on the river Angrais and at Rifle river, of which said Indians are to have the usufruct and occupancy for five years." Indigenous people had restraints pushed on them by the five-year allowance.

Early land sales in Virginia (1705–1713)

[edit]Scholarly author Buck Woodard used executive papers from Governor William H. Cabell in his article, "Indian Land sales and allotment in Antebellum Virginia" to discuss Indigenous reservations in America before 1705, specifically in Virginia.[25] He claims "the colonial government again recognized the Nottoway's land rights by treaty in 1713, at the conclusion of the Tuscaro War."[25] The indigenous peoples of America had land treaty agreements as early as 1713.[25]

The beginning of the Indigenous Reservation System in America (1763–1834)

[edit]

The American Indigenous Reservation system started with "the Royal Proclamation of 1763, where Great Britain set aside an enormous resource for Indians in the territory of the present United States."[26] The United States put forward another act when "Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830".[27] A third act pushed through was "the federal government relocated "portions of [the] 'Five Civilized Tribes' from the southeastern states in the Non-Intercourse Act of 1834."[28] All three of these laws set into motion the Indigenous Reservation system in the United States of America, resulting in the forceful removal of Indigenous peoples into specific land Reservations.[27]

Treaty between America and the Menominee Nation (1831)

[edit]Scholarly author James Oberly discusses "The Treaty of 1831 between the Menominee Nation and the United States"[29] in his article, "Decision on Duck Creek: Two Green Bay Reservations and Their Boundaries, 1816–1996", showing yet another treaty regarding Indigenous Reservations before 1850. There is a conflict between the Menomee Nation and the State of Wisconsin and "the 1831 Menomee Treaty … ran the boundary between the lands of the Oneida, known in the Treaty as the "New York Indians".[29] This Treaty from 1831 is the cause of conflicts and is disputed because the land was good hunting grounds.

1834 Trade and Intercourse Act (1834)

[edit]

The Trade and Intercourse Act of 1834 says "In the 1834 Indian Trade and Intercourse Act, the United States defined the boundaries of Indian County."[30] Also, "For Unrau, Indigenous Country is less on Indigenous homeland and more a place where the U.S. removed Indians from east of the Mississippi River and applied unique laws."[30] The United States of America applied laws on Indigenous Reservations depending on where they were located like the Mississippi River. This act came too, because "the federal government began to compress Indigenous lands because it needed to send troops to Texas during the Mexican-American War and protect American immigration traveling to Oregon and California."[31] The Federal Government of America had their own needs and desires for Indigenous Land Reservations. He says, "the reconnaissance of explorers and other American officials understood that Indigenous Country possessed good land, bountiful game, and potential mineral resources."[31] The American Government claimed Indigenous land for their own benefits with these creations of Indigenous Land Reservations .

Indigenous Reservation System in Texas (1845)

[edit]States such as Texas had their own policy when it came to Indian Reservations in America before 1850. Scholarly author George D. Harmon discusses Texas' own reservation system which "Prior to 1845, Texas had inaugurated and pursued her own Indian Policy of the U.S."[32] Texas was one of the States before 1850 that chose to create their own reservation system as seen in Harmon's article, "The United States Indian Policy in Texas, 1845–1860."[33] The State of "Texas had given only a few hundred acres of land in 1840, for the purpose of colonization".[32] However, "In March 1847, … [a] special agent [was sent] to Texas to manage the Indian affairs in the State until Congress should take some definite and final action."[34] The United States of America allowed its states to make up their own treaties such as this one in Texas for the purpose of colonization.

Rise of Indian removal policy (1830–1868)

[edit]The passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 marked the systematization of a U.S. federal government policy of moving Native populations away from European-populated areas, whether forcibly or voluntarily.

One example was the Five Civilized Tribes, who were removed from their historical homelands in the Southeastern United States and moved to Indian Territory, in a forced mass migration that came to be known as the Trail of Tears. Some of the lands these tribes were given to inhabit following the removals eventually became Indian reservations.

In 1851, the United States Congress passed the Indian Appropriations Act which authorized the creation of Indian reservations in Indian Territory (which became Oklahoma). Relations between white settlers and Natives had grown increasingly worse as the settlers encroached on territory and natural resources in the West.[35]

Forced assimilation (1868–1887)

[edit]

In 1868, President Ulysses S. Grant pursued a "Peace Policy" as an attempt to avoid violence.[36] The policy included a reorganization of the Indian Service, with the goal of relocating various tribes from their ancestral homes to parcels of lands established specifically for their inhabitation. The policy called for the replacement of government officials by religious men, nominated by churches, to oversee the Indian agencies on reservations in order to teach Christianity to the Native American tribes. The Quakers were especially active in this policy on reservations.[37]

The policy was controversial from the start. Reservations were generally established by executive order. In many cases, white settlers objected to the size of land parcels, which were subsequently reduced. A report submitted to Congress in 1868 found widespread corruption among the federal Native American agencies and generally poor conditions among the relocated tribes.

The Indian Appropriations Act of 1871 had two significant sections. First, the Act ended United States recognition of additional Native American tribes or independent nations and prohibited additional treaties. Thus, it required the federal government no longer interact with the various tribes through treaties, but rather through statutes:

That hereafter no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty: Provided, further, that nothing herein contained shall be construed to invalidate or impair the obligation of any treaty heretofore lawfully made and ratified with any such Indian nation or tribe.

The 1871 Act also made it a federal crime to commit murder, manslaughter, rape, assault with intent to kill, arson, burglary, and larceny within any Territory of the United States.[citation needed]

Many tribes ignored the relocation orders at first and were forced onto their limited land parcels. Enforcement of the policy required the United States Army to restrict the movements of various tribes. The pursuit of tribes in order to force them back onto reservations led to a number of wars with Native Americans which included some massacres. The most well-known conflict was the Sioux War on the northern Great Plains, between 1876 and 1881, which included the Battle of Little Bighorn. Other famous wars in this regard included the Nez Perce War and the Modoc War, which marked the last conflict officially declared a war.

By the late 1870s, the policy established by President Grant was regarded as a failure, primarily because it had resulted in some of the bloodiest wars between Native Americans and the United States. By 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes began phasing out the policy, and by 1882 all religious organizations had relinquished their authority to the federal Indian agency.

Plenary Power

[edit]The 1871 Act was affirmed in 1886 by the U.S. Supreme Court, in United States v. Kagama, which affirmed that the Congress has plenary power over all Native American tribes within its borders by rationalization that "The power of the general government over these remnants of a race once powerful ... is necessary to their protection as well as to the safety of those among whom they dwell".[40] The Supreme Court affirmed that the U.S. Government "has the right and authority, instead of controlling them by treaties, to govern them by acts of Congress, they being within the geographical limit of the United States. ... The Indians owe no allegiance to a State within which their reservation may be established, and the State gives them no protection."[41]

Allotment Era (1887–1934)

[edit]In 1887, Congress undertook a significant change in reservation policy by the passage of the Dawes Act, or General Allotment (Severalty) Act. The act ended the general policy of granting land parcels to tribes as-a-whole by granting small parcels of land to individual tribe members. In some cases, for example, the Umatilla Indian Reservation, after the individual parcels were granted out of reservation land, the reservation area was reduced by giving the "excess land" to white settlers. The individual allotment policy continued until 1934 when it was terminated by the Indian Reorganization Act.

Passed by Congress in 1887, the "Dawes Act" was named for Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, Chairman of the Senate's Indian Affairs Committee. It came as another crucial step in attacking the tribal aspect of the Indians of the time. In essence, the act broke up the land of most all tribes into modest parcels to be distributed to Indian families, and those remaining were auctioned off to white purchasers. Indians who accepted the farmland and became "civilized" were made American citizens. But the Act itself proved disastrous for Indians, as much tribal land was lost, and cultural traditions destroyed. Whites benefited the most; for example, when the government made 2 million acres (8,100 km2) of Indian lands available in Oklahoma, 50,000 white settlers poured in almost instantly to claim it all (in a period of one day, April 22, 1889).

Evolution of relationships: The evolution of the relationship between tribal governments and federal governments has been glued together through partnerships and agreements. Also running into problems of course such as finances which also led to not being able to have a stable social and political structure at the helm of these tribes or states.[42]

The Reorganization Era

[edit]The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, also known as the Howard-Wheeler Act, was sometimes called the Indian New Deal and was initiated by John Collier. It laid out new rights for Native Americans, reversed some of the earlier privatization of their common holdings, and encouraged tribal sovereignty and land management by tribes. The act slowed the assignment of tribal lands to individual members and reduced the assignment of "extra" holdings to nonmembers.

For the following 20 years, the U.S. government invested in infrastructure, health care, and education on the reservations. Likewise, over two million acres (8,000 km2) of land were returned to various tribes. Within a decade of Collier's retirement the government's position began to swing in the opposite direction. The new Indian Commissioners Myers and Emmons introduced the idea of the "withdrawal program" or "termination", which sought to end the government's responsibility and involvement with Indians and to force their assimilation.

The Indians would lose their lands but were to be compensated, although many were not. Even though discontent and social rejection killed the idea before it was fully implemented, five tribes were terminated—the Coushatta, Ute, Paiute, Menominee and Klamath—and 114 groups in California lost their federal recognition as tribes. Many individuals were also relocated to cities, but one-third returned to their tribal reservations in the decades that followed.

In 1934, the Indian Reorganization Act, codified as Title 25, Section 476 of the U.S. Code, allowed Indian nations to select from a catalogue of constitutional documents that enumerated powers for tribes and for tribal councils. Though the Act did not specifically recognize the Courts of Indian Offenses, 1934 is widely considered to be the year when tribal authority, rather than United States authority, gave the tribal courts legitimacy. John Collier and Nathan Margold wrote the solicitor's opinion, "Powers of Indian Tribes" which was issued October 25, 1934, and commented on the wording of the Indian Reorganization Act. This opinion stated that sovereign powers inhered in Indian tribes except for where they were restricted by Congress. The opinion stated that "Conquest has brought the Indian tribes under the control of Congress, but except as Congress has expressly restricted or limited the internal powers of sovereignty vested in the Indian tribes such powers are still vested in the respective tribes and may be exercised by their duly constituted organs of government."[43]

The Termination Era

[edit]In 1953, Congress enacted Public Law 280, which gave some states extensive jurisdiction over the criminal and civil controversies involving Indians on Indian lands. Many, especially Indians, continue to believe the law unfair because it imposed a system of laws on the tribal nations without their approval.

In 1965, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit concluded that no law had ever extended provisions of the U.S. Constitution, including the right of habeas corpus, to tribal members brought before tribal courts. Still, the court concluded, "it is pure fiction to say that the Indian courts functioning in the Fort Belknap Indian community are not in part, at least, arms of the federal government. Originally they were created by federal executive and imposed upon the Indian community, and to this day the federal government still maintains a partial control over them." In the end however, the Ninth Circuit limited its decision to the particular reservation in question and stated, "it does not follow from our decision that the tribal court must comply with every constitutional restriction that is applicable to federal or state courts."

The Self-Determination Era

[edit]

Richard Nixon took office as president in 1969. From 1969 to 1974, the Richard Nixon administration made important changes to United States policy towards Native Americans through legislation and executive action. President Richard Nixon advocated a reversal of the long-standing policy of "termination" that had characterized relations between the U.S. federal government and American Indians in favor of "self-determination." The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act restructured indigenous governance in Alaska, creating a unique structure of Native Corporations. Some of the most notable instances of American Indian activism occurred under the Nixon Administration, including the Occupation of Alcatraz and the Occupation of Wounded Knee.

It was under his administration that Washington state Senator Henry M. Jackson and Senate Subcommittee on Indian Affairs aide Forrest J. Gerard were most active in their reform efforts. The work of Jackson and Gerard mirrored the demands of Indians for "self-determination." Nixon called for an end to termination and provided a direct endorsement of "self-determination."

In a 1970 address to Congress, Nixon articulated his vision of self-determination. He explained, "The time has come to break decisively with the past and to create the conditions for a new era in which the Indian future is determined by Indian acts and Indian decisions."[44] Nixon continued, "This policy of forced termination is wrong, in my judgment, for a number of reasons. First, the premises on which it rests are wrong. Termination implies that the federal government has taken on a trusteeship responsibility for Indian communities as an act of generosity toward a disadvantaged people and that it can therefore discontinue this responsibility on a unilateral basis whenever it sees fit."[44] Nixon's overt renunciation of the long-standing termination policy was the first of any President in the post-World War II era. While many modern courts in Indian nations today have established full faith and credit with state courts, the nations still have no direct access to U.S. courts. When an Indian nation files suit against a state in U.S. court, they do so with the approval of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In the modern legal era, the courts and Congress have, however, further refined the often competing jurisdictions of tribal nations, states and the United States in regard to Indian law.

Today the United States recognizes 574 Tribal nations, 229 of which are in Alaska.[45][46] The National Congress of American Indians explains, "Native peoples and governments have inherent rights and a political relationship with the U.S. government that does not derive from race or ethnicity."[46]

In the 1978 case of Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, the Supreme Court, in a 6–2 opinion authored by Justice William Rehnquist, concluded that tribal courts do not have jurisdiction over non-Indians (the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court at that time, Warren Burger, and Justice Thurgood Marshall filed a dissenting opinion). But the case left unanswered some questions, including whether tribal courts could use criminal contempt powers against non-Indians to maintain decorum in the courtroom, or whether tribal courts could subpoena non-Indians.

A 1981 case, Montana v. United States, clarified that tribal nations possess inherent power over their internal affairs, and civil authority over non-members on fee-simple lands within its reservation when their "conduct threatens or has some direct effect on the political integrity, the economic security, or the health or welfare of the tribe."

Other cases of those years precluded states from interfering with tribal nations' sovereignty. Tribal sovereignty is dependent on, and subordinate to, only the federal government, not states, under Washington v. Confederated Tribes of Colville Indian Reservation (1980). Tribes are sovereign over tribal members and tribal land, under United States v. Mazurie (1975).[19]

In Duro v. Reina, 495 U.S. 676 (1990), the Supreme Court held that a tribal court does not have criminal jurisdiction over a non-member Indian, but that tribes "also possess their traditional and undisputed power to exclude persons who they deem to be undesirable from tribal lands. ... Tribal law enforcement authorities have the power if necessary, to eject them. Where jurisdiction to try and punish an offender rests outside the tribe, tribal officers may exercise their power to detain and transport him to the proper authorities." In response to this decision, Congress passed the 'Duro Fix', which recognizes the power of tribes to exercise criminal jurisdiction within their reservations over all Indians, including non-members. The Duro Fix was upheld by the Supreme Court in United States v. Lara, 541 U.S. 193 (2004).

Federal acknowledgment

[edit]Following the decisions made by the Indian Claims Commission in the 1950s, the BIA in 1978 published final rules with procedures that groups had to meet to secure federal tribal acknowledgment. There are seven criteria. Four have proven troublesome for most groups to prove: long-standing historical community, outside identification as Indians, political authority, and descent from a historical tribe. Tribes seeking recognition must submit detailed petitions to the BIA's Office of Federal Acknowledgment.

To be formally recognized as an Indian tribe, the US Congress can legislate recognition or a tribe can meet the seven criteria outlined by the Office of Federal Acknowledgment. These seven criteria are summarized as:

- 83.7(a): "Indian entity identification: The petitioner demonstrates that it has been identified as an American Indian entity on a substantially continuous basis since 1900."[47]

- 83.7(b): "Community: The petitioner demonstrates that it comprises a distinct community and existed as a community from 1900 until the present."[47]

- 83.7(c): "Political influence or authority: The petitioner demonstrates that it has maintained political influence or authority over its members as an autonomous entity from 1900 until the present."[47]

- 83.7(d): "Governing document: The petitioner provides a copy of the group's present governing document including its membership criteria. In the absence of a written document, the petitioner must provide a statement describing in full its membership criteria and current governing procedures."[47]

- 83.7(e): "Descent: The petitioner demonstrates that its membership consists of individuals who descend from a historical Indian tribe or from historical Indian tribes which combined and functioned as a single autonomous political entity."[47]

- 83.7(f): "Unique membership: The petitioner demonstrates that the membership of the petitioning group is composed principally of persons who are not members of any acknowledged North American Indian tribe."[47]

- 83.7(g): "Congressional termination: The Department demonstrates that neither the petitioner nor its members are the subject of congressional legislation that has expressly terminated or forbidden the Federal relationship."[47]

The federal acknowledgment process can take years, even decades; delays of 12 to 14 years have occurred. The Shinnecock Indian Nation formally petitioned for recognition in 1978 and was recognized 32 years later in 2010. At a Senate Committee on Indian Affairs hearing, witnesses testified that the process was "broken, long, expensive, burdensome, intrusive, unfair, arbitrary and capricious, less than transparent, unpredictable, and subject to undue political influence and manipulation."[48][49]

Recent additions

[edit]The number of tribes increased to 567 in May 2016 with the inclusion of the Pamunkey tribe in Virginia who received their federal recognition in July 2015.[50] The number of tribes increased to 573 with the addition of six tribes in Virginia under the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017, signed in January 2018 after the annual list had been published.[51] In July 2018 the United States' Federal Register issued an official list of 573 tribes that are Indian Entities Recognized and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs.[51] The Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana became the 574th tribe to gain federal recognition on December 20, 2019. The website USA.gov, the federal government's official web portal, also maintains an updated list of tribal governments. Ancillary information present in former versions of this list but no longer contained in the current listing has been included here in italic print.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit] This article incorporates public domain material from 85 FR 5462 - Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs. United States government.

This article incorporates public domain material from 85 FR 5462 - Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs. United States government.

- ^ a b "Why Tribes Exist Today in the United States". Frequently Asked Questions. Bureau of Indian Affairs, US Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on July 14, 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- ^ United States v. Sandoval, 231 U.S. 28 (1913)

- ^ Sheffield (1998) p. 56

- ^ Constitution of the United States of America: Article. I.

- ^ American Indian Policy Center. 2005. St. Paul, MN. 4 October 2008

- ^ Cherokee Nations v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831)

- ^ Additional amendments to the United States Constitution

- ^ Charles F. Wilkinson, Indian tribes as sovereign governments: a sourcebook on federal-tribal history, law, and policy, AIRI Press, 1988

- ^ Conference of Western Attorneys General, American Indian Law Deskbook, University Press of Colorado, 2004

- ^ N. Bruce Duthu, American Indians and the Law, Penguin/Viking, 2008

- ^ Robert J. McCarthy, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Federal Trust Obligation to American Indians, 19 BYU J. PUB. L. 1 (December, 2004)

- ^ "40d. Life on the Reservations". U.S. History. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Glover, Jeffrey (2014). Paper Sovereigns: Anglo-Native Treaties and the Law of Nations, 1604-1664. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 9–14. ISBN 9780812245967.

- ^ "This Day in Geographic History: First Indian Reservation". National Geographic Society. July 18, 2014. Archived from the original on July 12, 2018. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c Thomas, JD (August 29, 2013). "The Colonies' First and New Jersey's Only Indian Reservation". Accessible Archives Inc. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ a b Kephart, Bill & Mary (November 7, 2010). "The Kepharts: Cohawkin, Raccoon Creek, Narraticon all names left by Lenni-Lenape in Gloucester County". NJ.com. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

In 1758, the Colonial Legislature purchased land in Burlington County for a reservation. It was the first Indian Reservation in America and was called Edgepelick. Governor Francis Bernard called it Brotherton. Today the area is known as Indian Mills. In 1801, an act was passed directing the sale of Brotherton, with the proceeds used to send the remaining Lenape to the Stockbridge Reservation near Oneida, New York. There they formed a settlement called Statesburg.

November 7, 2010 - ^ a b c d e Remarks on the Plan for Regulating the Indian Trade, September 1766 – October 1766, Founders Online

- ^ Belko, William S. (2004). "John C. Calhoun and the Creation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs: an Essay on Political Rivalry, Ideology, and Policymaking in the Early Republic". South Carolina Historical Magazine. 105 (3): 170–97. JSTOR 27570693.

- ^ a b Miller, Robert J. (2021-03-18). "The Most Significant Indian Law Decision in a Century | The Regulatory Review". The Regulatory Review. University of Pennsylvania Law School. Retrieved 2022-12-01.

- ^ Canby Jr., William C. American Indian Law in a Nutshell (Nutshells). p. 20.>

- ^ Andrew Jackson, "A letter by Andrew Jackson, President of the United States of America, Indian Treaties and Laws and Regulations Relating to Indian Affairs: To Which Is Added, An Appendix. Way and Gideon, Printers", 1826.

- ^ Andrew Jackson, "A letter by Andrew Jackson, President of the United States of America, Indian Treaties and Laws and Regulations Relating to Indian Affairs: To Which Is Added, An Appendix. Way and Gideon, Printers", 1826, 580.

- ^ a b Martin Van Buren, President of the United States of America, "Treaties between the United States and the Saginaw tribe of Chippewas", 1837.

- ^ John Forsyth, the Secretary of State On behalf of, President Buren, Martin Van of the United States. Martin Van Buren, "Treaty Between: The United States of America and the First Christian and Orchard Parties of the Oneida Indians," 1838.

- ^ a b c Buck Woodard, "Indian Land sales and allotment in Antebellum Virginia: trustees, tribal agency, and the Nottoway Reservation", American Nineteenth Century History 17. no. 2 (2016): page number. 161-180.

- ^ James E Togerson "Indians against Immigrants: Old Rivals, New Rules: A Brief Review and Comparison of Indian Law in the Contiguous United States, Alaska, and Canada." American Indian Law Review 14, no. 1 (1988), 58.

- ^ a b James E Togerson "Indians against Immigrants: Old Rivals, New Rules: A Brief Review and Comparison of Indian Law in the Contiguous United States, Alaska, and Canada." American Indian Law Review 14, no. 1 (1988), 57–103.

- ^ James E Togerson "Indians against Immigrants: Old Rivals, New Rules: A Brief Review and Comparison of Indian Law in the Contiguous United States, Alaska, and Canada." American Indian Law Review 14, no. 1 (1988), 59.

- ^ a b James Oberly, ""Decision on Duck Creek: Two Green Bay Reservations and Their Boundaries, 1816–1996", American Indian Culture & Research Journal 24, no. 3 (2000): 39–76.

- ^ a b William J Bauer, "The Rise and Fall of Indian Country, 1825–1855", History: Reviews of New Books 36, no. 2 (Winter 2008): 50.

- ^ a b William J Bauer, "The Rise and Fall of Indian Country, 1825–1855", History: Reviews of New Books 36, no. 2 (Winter 2008): 51.

- ^ a b George D Harmon, "The United States Indian Policy in Texas, 1845–1860", The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 17, no. 3 (1930): 379.

- ^ George D Harmon, "The United States Indian Policy in Texas, 1845–1860", The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 17, no. 3 (1930)

- ^ George D Harmon, "The United States Indian Policy in Texas, 1845–1860", The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 17, no. 3 (1930): 380.

- ^ Bennett, Elmer (2008). Federal Indian Law. The Lawbook Exchange. pp. 201–203. ISBN 9781584777762.

- ^ "President Grant advances "Peace Policy" with tribes". US National Library of Medicine. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ Miller Center, University of Virginia Archived April 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ Onecle (November 8, 2005). "Indian Treaties". Retrieved 2009-03-31.

- ^ 25 U.S.C. § 71. Indian Appropriation Act of March 3, 1871, 16 Stat. 544, 566

- ^ "U.S. v Kagama, 118 U.S. 375 (1886), Filed May 10, 1886". FindLaw, a Thomson Reuters business. Retrieved 2012-04-29.

- ^ "United States v. Kagama – 118 U.S. 375 (1886)". Justia. Retrieved 2012-04-29.

- ^ "Historical Tribal Sovereignty & Relations | Native American Financial Services Association". August 7, 2012. Retrieved 2019-10-11.

- ^ Margold, Nathan R. "Powers of Indian Tribes". Solicitor's Opinions. University of Oklahoma College of Law. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Richard Nixon Special Message to Congress on Indian Affairs". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ "Native American Policies". U.S. Department of Justice. 2014-06-16. Retrieved 2019-07-07.

- ^ a b "Tribal Nations & the United States: An Introduction". National Congress of American Indians. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "25 CFR Part 83 – Procedures for Federal Acknowledgment of Indian Tribes" (PDF). Office of Federal Acknowledgment. Office of Indian Affairs, US Department of the Interior. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Toensing, Gale Courey (13 September 2018). "Federal Recognition Process: A Culture of Neglect". Indian Country Today. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Fixing the Federal Acknowledgment Process Archived November 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine (S. Hrg. 111-470), Hearing Before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate (Nov. 4, 2009). Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ Federal Acknowledgment of the Pamunkey Indian Tribe Archived 2015-07-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Bureau of Indian Affairs, Interior. (January 8, 2024). "Notice Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs". Federal Register. 89 (944): 944–48. Archived from the original on January 15, 2024. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

Further reading

- J. P. Allen and E. Turner, Changing Faces, Changing Places: Mapping Southern Californians (Northridge, CA: The Center for Geographical Studies, California State University, Northridge, 2002).

- George Pierre Castle and Robert L. Bee, eds., State and Reservation: New Perspectives on Federal Indian Policy (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1992)

- Richmond L. Clow and Imre Sutton, eds., Trusteeship in Change: Toward Tribal Autonomy in Resource Management (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2001).

- Wade Davies and Richmond L. Clow, American Indian Sovereignty and Law: An Annotated Bibliography (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2009).

- T. J. Ferguson and E. Richard Hart, A Zuni Atlas (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985)

- David H. Getches, Charles F. Wilkinson, and Robert A. Williams, Cases and Materials on Federal Indian Law, 4th ed. (St. Paul: West Group, 1998).

- Klaus Frantz, "Indian Reservations in the United States", Geography Research Paper 241 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

- James M. Goodman, The Navajo Atlas: Environments, Resources, People, and History of the Diné Bikeyah (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1982).

- J. P. Kinney, A Continent Lost: A Civilization Won: Indian Land Tenure in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1937)

- Francis Paul Prucha, Atlas of American Indian Affairs (Norman: University of Nebraska Press, 1990).

- C. C. Royce, comp., Indian Land Cessions in the United States, 18th Annual Report, 1896–97, pt. 2 (Wash., D. C.: Bureau of American Ethnology; GPO 1899)

- Imre Sutton, "Cartographic Review of Indian Land Tenure and Territoriality: A Schematic Approach", American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 26:2 (2002): 63–113.

- Imre Sutton, Indian Land Tenure: Bibliographical Essays and a Guide to the Literature (NY: Clearwater Publ. 1975).

- Imre Sutton, ed., "The Political Geography of Indian Country", American Indian Culture and Resource Journal, vol. 15, no. 2 (1991):1–169.

- Imre Sutton, "Sovereign States and the Changing Definition of the Indian Reservation", Geographical Review, vol. 66, no. 3 (1976): 281–95.

- Veronica E. Velarde Tiller, ed., Tiller's Guide to Indian Country: Economic Profiles of American Indian Reservations (Albuquerque: BowArrow Pub., 1996/2005)

- David J. Wishart and Oliver Froehling, "Land Ownership, Population and Jurisdiction: the Case of the 'Devils Lake Sioux Tribe v. North Dakota Public Service Commission'", American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 20(2): 33–58 (1996).

- Laura Woodward-Ney, Mapping Identity: The Coeur d'Alene Indian Reservation, 1803–1902 (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2004)

See also

[edit]- Indian country

- Tribal sovereignty in the United States

- Federal Indian Policy

- Domestic dependent nations

- Suzerainty

- Indian Claims Commission

- Indian colony

- Native Hawaiians

- Hawaiian home land

- Indian country

- List of historical Indian reservations in the United States

- List of Indian reservations in the United States

- List of federally recognized tribes by state

- List of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States

- List of Alaska Native tribal entities

- List of Indian reservations in the United States

- Native American reservation politics

External links

[edit]- BIA full-size Indian reservations in the continental United States – National Park Service

- U.S. Census tallies for Indian reservations

- Chapter 5: American Indian and Alaska Native Areas, U.S. Census Bureau, Geographic Areas Reference manual (PDF)

- Tribal Leaders Directory

- Native American Technical Corrections Act of 2003

- Gambling on the reservation April 2004 Christian Science Monitor article with links to other Monitor articles on the topic

- Henry Red Cloud of Oglala Lakota Tribe on the Recession's Toll on Reservations—video report by Democracy Now!

- Tribal Justice & Safety. at the U.S. Department of Justice

- "Public Law 280 and Law Enforcement in Indian Country – Research Priorities"

- Native American people

- Federally recognized tribes in the United States

- Contiguous United States

- First-level administrative divisions by country

- Administrative divisions in North America

- Political divisions of the United States

- Types of administrative division

- American Indian reservations

- Native American topics

- Aboriginal title in the United States

- Native American culture

- History of racial segregation in the United States

- United States Bureau of Indian Affairs