Eanna

Sumerian: 𒂍𒀭𒈾 | |

Part of the front of Inanna's temple | |

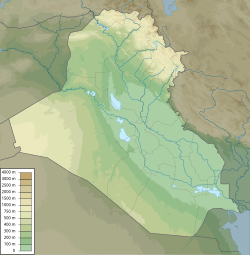

| Location | Uruk, Sumer (modern Warka, Muthanna Governorate, Iraq) |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 31°3′22″N 45°6′33″E / 31.05611°N 45.10917°E |

| Type | Temple |

| Part of | Eanna District |

| History | |

| Material | Mudbrick, Clay, Gypsum |

| Founded | c. 3400-3100 BCE |

| Abandoned | c. 200 BCE |

| Periods | Uruk period to Seleucid |

| Cultures | Sumerian, Akkadian |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | ruined |

E-anna (Sumerian: 𒂍𒀭𒈾 É-AN.NA, "House of Heaven"), also referred to as the Temple of Inanna, was monumental ancient Sumerian temple complex in Uruk. Considered the "residence" of Inanna, it was among the most prominent and influential religious institutions of ancient Mesopotamia. Mentioned throughout the Epic of Gilgamesh and various other texts, the evolution of the gods to whom the temple was dedicated to over time is also the subject of scholarly study.[1]

Temple complex and administration

[edit]Originally constructed during the Uruk period (c. 4000–3100 BCE), Eanna evolved into a major urban and administrative center.[2] As with other Mesopotamian temples, Eanna was a major economic hub where agricultural estates, trade networks, and a large labor force including artisans, scribes, herdsmen, and priests were managed and administered.[3]

The temple’s bureaucratic apparatus managed the redistribution of goods and offerings, with records inscribed in cuneiform tablets detailing transactions involving grain, textiles, oil, and livestock. These activities reflect Eanna’s dual function as a sacred sanctuary and an institutional authority within the city-state. Control of the temple meant access to both religious prestige and material wealth, further embedding Inanna’s cult into the socio-political fabric of Sumerian urban life.[4]

Cult of Inanna

[edit]Priestesses and gender roles

[edit]The cult of Inanna was distinguished by its inclusion of diverse gender roles and unique religious specialists. High-ranking priestesses such as the entu held authoritative liturgical roles and were often members of elite families, sometimes even of royal lineage. These women performed ritual functions and may have been central figures in the sacred marriage rites (hieros gamos), symbolizing the union between the goddess and the king.[5]

Inanna’s cult also notably included gala-priests, a gender-nonconforming clergy class who performed lamentations and musical rites, often in Sumerian dialects associated with feminine speech known as Emesal. The gala’s androgynous identity is reflected in lexical lists and administrative texts, where they are described using grammatically feminine forms or with references to altered sexuality.[6] Their ritual role was particularly significant during mourning ceremonies and transitional rites associated with death and rebirth—a thematic focus of Inanna’s mythos.[7]

Scholars have argued that the gender diversity in Inanna’s cult reflects the goddess’s own transgressive nature. Myths such as the Descent of Inanna into the Underworld dramatize her crossing of ontological boundaries, mirrored in the human roles that served her temple.[8]

Festivals and rituals

[edit]Festivals dedicated to Inanna were integral to the liturgical calendar and reinforced her authority within both religious and civic life. Chief among these was the Akitu festival, celebrated at the New Year, during which Inanna’s relationship to divine kingship and agricultural fertility was ritually dramatized. These events often included processions, hymns, and ceremonial performances aimed at renewing cosmic order.[9]

The most distinctive cultic event associated with Inanna was the sacred marriage rite (hieros gamos), wherein the king of Uruk would ritually unite with the entu (high priestess) acting as the embodiment of Inanna. This ritual was symbolic of divine favor and agricultural fecundity, believed to ensure the prosperity of the city and land. The rite is extensively described in Sumerian temple hymns, particularly those composed by the priestess Enheduanna, who linked the rite to the affirmation of royal and divine legitimacy.[10]

Other rituals involved symbolic re-enactments of Inanna’s descent into the underworld and return, representing themes of death, rebirth, and seasonal renewal. Such liturgies were public spectacles that reinforced communal identity and cosmological alignment through ritual drama and recitation.[11]

Texts

[edit]From Tablet One:[12]

He carved on a stone stela all of his toils,

and built the wall of Uruk-Haven,

the wall of the sacred Eanna Temple, the holy sanctuary.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jeffrey H. Tigay (1982). The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 9780865165465.

- ^ Leick, Gwendolyn (2002). Mesopotamia: the invention of the city. London: Penguin. pp. 42–48. ISBN 978-0-14-026574-3.

- ^ Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998). Daily life in ancient Mesopotamia. Internet Archive. Westport, Conn. : Greenwood Press. pp. 141–145. ISBN 978-0-313-29497-6.

- ^ Postgate, John N. (2009). Early Mesopotamia: society and economy at the dawn of history (Rev. 1994, repr. 2009 ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 98–103. ISBN 978-0-415-11032-7.

- ^ Asher-Greve, Julia M. (2013). Goddesses in context : on divine powers, roles, relationships and gender in Mesopotamian textual and visual sources. Internet Archive. Fribourg : Academic Press Fribourg ; Göttingen : Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 205–210. ISBN 978-3-7278-1738-0.

- ^ Leick, Gwendo (1994). Sex and Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature. Routledge. pp. 22–25. ISBN 0-415-06534-8.

- ^ Bahrani, Zainab (2001). Women of Babylon: Gender and Representation in Mesopotamia. Routledge. pp. 80–85. ISBN 0-415-21830-6.

- ^ Black, Jeremy A.; Green, Anthony; Rickards, Tessa (1992). Gods, demons, and symbols of ancient Mesopotamia: an illustrated dictionary. British Museum. London: Published by British Museum Press for the Trustees of the British Museum. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8.

- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild (1978). The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 55–60. ISBN 978-0-300-02291-9.

- ^ Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983). Inanna, queen of heaven and earth: her stories and hymns from Sumer. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 36–39. ISBN 978-0-06-014713-6.

- ^ Samet, Nili (2021). The Lamentation over the Destruction of Ur. Mesopotamian Civilizations. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-1-57506-883-1.

- ^ "Epic of Gilgamesh: Tablet I".