Draft:Phaéton (Saint-Saëns)

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take 3 months or more, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 2,400 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

| Phaéton | |

|---|---|

| by Camille Saint-Saëns | |

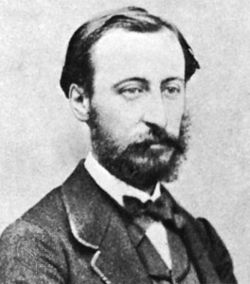

Saint-Saëns circa 1875 | |

| English | Phaethon |

| Key | C Major |

| Catalogue | R170 |

| Opus | 39 |

| Period | Romanticism |

| Genre | Symphonic Poem |

| Composed | 1873 |

| Dedication | Madame Berthe Pochet |

| Published | 1875 |

| Publisher | Éditions Durand-Schönewerk & Cie |

| Duration | 8-10 minutes |

| Movements | 1 |

| Scoring | Symphony Orchestra |

| Premiere | |

| Date | December 7, 1873 |

| Location | Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris |

| Conductor | Édouard Colonne |

| Performers | Concert National |

Phaéton (Phaethon), Op. 39, is a symphonic poem for orchestra, composed by Camille Saint-Saëns in 1873. It is the second in his genre's tetralogy, preceded by Le Rouet d'Omphale and followed by Danse macabre and La jeunesse d'Hercule. The work was premiered at the Théâtre du Châtelet in 7 December 1873, performed by the Concert National conducted by Édouard Colonne. Despite its cool reception, the work has managed to remain in the borders of the repertoire, but is largely overshadowed in popularity by Danse Macabre.

Background

[edit]Hector Berlioz was an early influence of Camille Saint-Saëns, and his four programmatic symphonies paved the way for the introduction of the symphonic poem by Franz Liszt.[1] While César Franck was the first French composer to write a symphonic poem between 1845–46, titled Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne,[2] it was neither performed nor published during the composer's lifetime.[3] Unaware of Franck's work, Saint-Saëns was an early admirer of the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt.[4]

je n’avais pas subi sa fascination personnelle, je ne l’avais encore ni vu ni entendu quand je me suis épris à la lecture de ses premiers Poèmes symphoniques, quand ils m’ont indiqué le chemin où je devais rencontrer plus tard la Danse macabre, le Rouet d’Omphale et autres œuvres de même nature

I had not experienced his personal fascination, I had not yet seen or heard him when I fell in love with his first symphonic poems, when they showed me the path on which I was later to meet Danse macabre, Le Rouet d’Omphale op.31 and other works of the same nature

— Portraits et Souvenirs, "Franz Liszt" (1900)

A meeting with the Hungarian composer was the inspiration behind Saint-Saëns's Le Rouet d'Omphale,[5] but their approach to the genre were quite different. In Liszt's conception of program music, musical form always took precedence over the extra-musical source.[6] Saint-Saëns's instead began with details that were worked into large, more abstract forms. According to musicologist Timothy Flynn, "This approach would suggest that Saint-Saéns was thinking more symphonically and less programmatically."[7]

Like Liszt, Saint-Saëns made use of the thematic transformation technique, in which a theme is continuously transformed to suit different moods or scenes of a story, while bringing formal unity and structure to the music.[8] Saint-Saëns would employ this technique in other works, such as in his Symphony No. 3 in C minor.[9]

Saint-Saëns had several interests beyond music, and ancient history was one of them. This interest reflects not only in three of the four symphonic poems, but in the chosen texts of several hymns and opera libretti. Later he would even write an essay titled "Note on the Theater Sets of Roman Antiquity"[10] It is possible the piece may have been inspired by Jean-Baptiste Lully's opera Phaëton[11]

Composition

[edit]

The manuscript was completed on 12 March 1873, being dedicated to Berthe Bochet, a close pupil of the composer. Saint-Saëns own mother later transcribed and corrected the score.[12] It was written during a period of failing health due to an exhausting workload comprised of composition, teaching, as well as concert and organ performances at La Madeleine.[13] It was played in a two-piano reduction on 4 March 1874, performed by Marie and Alfred Jaëll. After its premiere, it was published by Éditions Durand-Schönewerk & Cie in July 1785.[14]

Musicologist Daniel Fallon remarks the technical similarity between Le Rouet d'Omphale and Phaéton, both featuring a rhythmic motive that plays throughout the piece, while at the same time they are opposites in character. Le Rouet d'Omphale is sensuous and delicate in nature, while Phaéton is bold and dramatic.[15] Saint-Saëns himself drew comparison between the works with the following comment: "The central idea of 'Phaéton' is pride, as the central idea of 'Le Rouet d’Omphale' is lust."[16]

Program

[edit]

The work depicts the ancient Greek myth of Phaethon as narrated by Ovid in Books I–II of the Metamorphoses. In it Phaethon is the son of Helios who, out of a desire to have his parentage confirmed, travels to the sun god's palace in the east. He is recognised by his father and asks for the privilege of driving his chariot for a single day. Despite Helios' fervent warnings and attempts to dissuade him, counting the numerous dangers he would face in his celestial journey and reminding Phaethon that only he can control the horses, the boy is not dissuaded and does not change his mind.

He is then allowed to take the chariot's reins; his ride is disastrous, as he cannot keep a firm grip on the horses. As a result, he drives the chariot too close to the Earth, burning it, and too far from it, freezing it. In the end, after many complaints, from the stars in the sky to the Earth itself, Zeus strikes Phaethon with one of his lightning bolts, killing him instantly. His dead body falls into the river Eridanus, and his sisters, the Heliades, cry tears of amber and are turned to black poplar as they mourn him.[17]

The score is preceded by a program note, which is absent in the manuscript. It was written by Saint-Saëns himself.[18]

Phaéton a obtenu de conduire dans le Ciel le char du Soleil, son père. Mais ses mains inhabiles égarent les coursiers. Le char flamboyant, jeté hors de sa route, s'approche des régions terrestres. Tout l'univers va périr embrasé, lorsque Jupiter frappe de sa foudre l'imprudent Phaéton.

Phaethon has been granted permission to drive the chariot of his father, the Sun, across the sky. But his clumsy hands lead the steeds astray. The flaming chariot, thrown off course, approaches the earthly regions. The entire universe is about to perish in flames, when Jupiter strikes the imprudent Phaethon with his thunderbolt.

— Program note for the 1875 publication

Instrumentation

[edit]The piece is scored for symphony orchestra.[19]

- 1 piccolo

- 2 flutes (doubling piccolos)

- 2 oboes

- 2 clarinets

- 2 bassoons

- 1 contrabassoon (ad libitum)

- 4 horns (2 being natural horns)

- 2 trumpets

- 2 trombones

- 1 tubas

Arrangements

[edit]The piece has been extensively arranged, here is a list in chronological order.[20]

- Two pianos (December 1874) by Camille Saint-Saëns.

- Piano four-hand (September 1883) by Ernest Guiraud.

- Military Band (1898) by P. Lançon.

- Two pianos, violin, and optional violoncello (March 1900) by Léon Roques.

- Solo piano (December 1906) by A. Benfeld.

- Chamber orchestra (June 1910) by Hubert Mouton.

- Orchestra and harmonium (May 1914) by Hubert Mouton.

- Piano trio; piano, violin and violoncello (February 1928) by Roger Branga.

- Alternative version for piano, flute and violin.

- Alternative version for piano, flute, violoncello, with optional contrabassoon and clarinet.

Form

[edit]The piece is written in a single movement structured in several sections. Vincent d'Indy formally described the piece in two major sections, further subdivided in three each. On the other hand, Fallon claims it to be closer to a rondo.[21]

- I. Maestoso (𝅘𝅥 = 72) − Allº animato (𝅘𝅥 = 160) − (𝅘𝅥 = 168) - Le double plus lent (𝅘𝅥 = 80)

It begins with a brief maestoso introduction, with brass chords answered by rushing ascending scales from strings and woods. Fallon points the similarity between the opening with those from Liszt's Prometheus and Mazeppa.[22]. The allegro then starts with a rhythmic main theme in C major, presented by strings and harp and built on a nearly omnipresent ostinato figure, which is basis of the entire piece. It could be interpreted as Phaethon riding through the sky.[23] According to Fallon, this programmatic depiction of galloping horses through triplet rhythm brings comparisons not only with Liszt's Mazeppa, but also with Hector Berlioz's "The ride to the Abyss" from La Damnation de Faust, as well as Franz Schubert's lied Erlkönig. The same rhythmic pattern is found in Saint-Saëns La Chase du Burgrave from 1854.[24]

The theme modulates through several keys and more instruments are added. A crescendo leads to a solemn and expansive second theme in G major, presented by trumpets and trombones over violin ostinato figures. It possibly represents Phaethon himself. Violins then take it in piano with abundant thrills, before woodwinds take the material.[25] A kind of development section takes place with the return of the main theme, followed by a shortened version of the second while ascending through several keys. A transition then leads to a lyrical and cantabile third theme in E-flat major, scored for horns and clarinets while violins resume their accompaniment role.[26] It is then repeated as the rest of woodwinds join in. Fallon describes that the meaning of this piece has puzzled commentators, variously called "a song of bliss foreshadowing Phaethon's destiny", "the rising sun", "the splendour of the sun" and "a smiling view of terrestrial regions." Fallon himself claimed its purpose was to introduce lyrical contrast.[27]

After a chromatic descent of the theme on strings, the galloping motive returns in a tonally unstable way, possibly representing Phaethon's anxiety that will lead to his demise. The music modulates upwards from D to G major, before a fragment of the second theme returns on trombones between G major/minor, in canon with woodwinds. Fallon notes that the following chromatic ascension of violins and violas is a device Saint-Saëns would reuse in Danse Macabre.[28]. After several dissonant chords, an ominous motive appears on bassoon, contrabassoon, tuba, cellos and basses, which in turn leads to a chromatic ascension. A thunderous climax is achieved on full orchestra with an E-flat major chord, followed by a descending motive derived from the second theme. This fortisissimo climax represents Zeus killing Phaethon with his lightning bolt.[29]

The music then slows down, the third theme reappears on cellos in a funeral tone, which ccording to Fallon, is reminiscent of Liszt's Les Préludes. It is followed by the second theme on woodwinds. This is a clear example of thematic transformation, the material being transformed in a dirge to Phatheon. After a series of alternations between dominant and tonic, the work ends quietly.[30]

Performances and reception

[edit]The work was premiered at the Théâtre du Châtelet in 7 December 1873, performed by the Concert National conducted by Édouard Colonne. The parisian audience received the work with coldness, and critics dismissed the piece and program music in general, considered as unworthy of a serious musician.[31] A critic maintained that the chariot from mount Olympus was simply "the noise of a hack coming down from Montmartre" rather than the galloping fiery horses of Greek legend that inspired the piece.[32] Saint-Saëns was unaffected by critic's opinions, stating that music must be judged by itself instead of what it claims to represent.[33] The piece was better received in the ensuing performance in 12 December.[31]

It was then performed in Berlin on February 1876, played by Benjamin Bilse's Orchestra. Further performances took place in France and Germany.[20] In the United States, the work was first performed in Boston's Music Hall on 2 March 1876, performed by the Harvard Musical Association conducted by Carl Zerrahn. In the ensuing three years it was played in New York, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Baltimore, Pittsburg, St. Louis and Milwaukee. With the exception of the latter, these performances were played by the Theodore Thomas Orchestra led by Carl Zerrahn.[34]

In England, the work was first performed in London on 31 March 1898, played by the Royal Philharmonic Society of London directed by Sir Alexander Mackenzie. Saint-Saëns himself conducted the work in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on 25 June 1899.[35] The piece was performed during the Brussels International Exposition of 1910, alongside works by Dukas, Debussy, Franck, Fauré, and Berlioz.[36] Another noteworthy performance occasion was on 2 April 1913 during the inauguration of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, also conducted by the composer.[33]

Legacy

[edit]Despite its cool reception, the work has managed to remain in the borders of the repertoire, but is largely overshadowed in popularity by Danse Macabre. Several composers have praised the piece, such as Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky,[37] and Maurice Ravel.[38]

Brian Rees rated the work as the finest of the symphonic poems, praising the composer's melodic gift.[31] On the other hand, Saint-Saëns biographer Stephen Studd described the work as a failure, anti-climactic and the most disappointing of the symphonic poems.[13] Joseph Stevenson gave his appraisal as follows; "As is the case with all of the tone poems Saint-Saëns wrote in the 1870s, Phaéton is concise, dramatic, skillfully drawn, and very entertaining pictorial music. It deserves to be heard in concert much more often."[39] Fallon considered it to be one of the most successful of Saint-Saëns's symphonic poems.[40]

Recordings

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Laurence, Elliot Libin (2022). "Berlioz and Liszt". Symphony: The Romantic Era. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved March 28, 2025.

- ^ Ulrich, Homer (1952). Symphonic Music: Its Evolution since the Renaissance. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 228. Retrieved March 30, 2025.

- ^ Corleonis, Adrian. Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne (Franck) at AllMusic. Retrieved 27 March 2025.

- ^ Saint-Saëns, Camille (2012). Soret, Marie-Gabrielle (ed.). Écrits sur la musique et les musiciens 1870–1921 (in French). Vrin. p. 459. ISBN 978-2711624485.

- ^ Rees 2012, p. 165.

- ^ Johnston, Blair. Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne (Liszt) at AllMusic. Retrieved 27 March 2025.

- ^ Flynn, Timothy (2003). Camille Saint-Saëns: A Guide to Research. Routledge music bibliographies. New York: Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 9780815336198.

- ^ Cooper, Martin (1946). "The Symphonies". In Abraham, Gerald (ed.). The music of Tchaikovsky. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 25. Retrieved March 30, 2025.

- ^ Service, Tom (2014). "Symphony guide: Saint-Saëns's Third (the Organ symphony)". The Guardian. Retrieved March 30, 2025.

- ^ Saint-Saëns, Camille (1886). Note sur les décors de théâtre dans l'antiquité romaine [Note on the Theater Sets of Roman Antiquity] (in French). Paris: L. Baschet.

- ^ Fallon 1973, p. 256.

- ^ Rees 2012, p. 176.

- ^ a b Studd 1999, p. 97.

- ^ Ratner 2002, pp. 288–89.

- ^ Fallon 1973, p. 254.

- ^ Phaéton op. 39 R 170

- ^ Coolidge, Olivia E. (2001). Greek Myths. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 12–17. ISBN 978-0-61815426-5.

- ^ Tranchefort, François-René (1998). "Camille Saint-Saëns". Guide de la musique symphonique (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 9782213016382. Retrieved March 27, 2025.

- ^ Ratner 2002, p. 288.

- ^ a b Ratner 2002, p. 289.

- ^ Fallon 1973, pp. 277–78.

- ^ Fallon 1973, p. 260.

- ^ Fallon 1973, pp. 260–61.

- ^ Fallon 1973, pp. 262–63.

- ^ Fallon 1973, pp. 263–66.

- ^ Fallon 1973, pp. 266–69.

- ^ Fallon 1973, pp. 269–71.

- ^ Fallon 1973, pp. 271–72.

- ^ Fallon 1973, pp. 273–75.

- ^ Fallon 1973, pp. 277–76.

- ^ a b c Rees 2012, p. 177.

- ^ Fallon 1973, p. 255.

- ^ a b Ratner 2002, p. 290.

- ^ Johnson, Harold Earle (1979). First Performances in America to 1900: Works With Orchestra. Vol. 4 of Bibliographies in American Music. Boston, Michigan: College Music Society. p. 307. ISBN 9780911772944. Retrieved March 28, 2025.

- ^ Ratner 2002, pp. 289–90.

- ^ Holoman, Kern (2012). "Saint-Saëns at the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire de Paris (1903–1904)". In Pasler, Jann (ed.). Camille Saint-Saëns and His World. Bard Music Festival series. Princeton University Press. p. 130. ISBN 9780691155555.

- ^ Rees 2012, p. 303.

- ^ Flynn, Timothy (2003). Camille Saint-Saëns: A Guide to Research. Routledge music bibliographies. New York: Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 9780815336198.

- ^ Stevenson, Joseph. Phaéton, symphonic poem in C major, Op. 39 at AllMusic. Retrieved 31 March 2025.

- ^ Fallon 1973, p. 286.

Sources

[edit]- Studd, Stephen (1999). Saint-Saëns: A critical biography. London: Cygnus Arts. ISBN 978-1900541657.

- Rees, Brian (2012). Camille Saint-Saëns – A Life. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-57128-705-5.

- Fallon, Daniel (1973). The Symphonies and Symphonic Poems of Camille Saint-Saëns. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Xerox University Microfilms.

- Ratner, Sabina Teller (2002). Camille Saint-Saëns, 1835-1921: A Thematic Catalogue of His Complete Works. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198163206.

External links

[edit]- Phaéton: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project