Discriminant of an algebraic number field

In mathematics, the discriminant of an algebraic number field is a numerical invariant that, loosely speaking, measures the size of the (ring of integers of the) algebraic number field. More specifically, it is proportional to the squared volume of the fundamental domain of the ring of integers, and it regulates which primes are ramified.

The discriminant is one of the most basic invariants of a number field, and occurs in several important analytic formulas such as the functional equation of the Dedekind zeta function of , and the analytic class number formula for . A theorem of Hermite states that there are only finitely many number fields of bounded discriminant, however determining this quantity is still an open problem, and the subject of current research.[1]

The discriminant of can be referred to as the absolute discriminant of to distinguish it from the relative discriminant of an extension of number fields. The latter is an ideal in the ring of integers of , and like the absolute discriminant it indicates which primes are ramified in . It is a generalization of the absolute discriminant allowing for to be bigger than ; in fact, when , the relative discriminant of is the principal ideal of generated by the absolute discriminant of .

Definition

[edit]Let be an algebraic number field, and let be its ring of integers. Let be an integral basis of (i.e. a basis as a -module), and let be the set of embeddings of into the complex numbers (i.e. injective ring homomorphisms ). The discriminant of is the square of the determinant of the matrix whose -entry is . Symbolically,

Equivalently, the trace from to can be used. Specifically, define the trace form to be the matrix whose -entry is . This matrix equals , so the square of the discriminant of is the determinant of this matrix.

The discriminant of an order in with integral basis is defined in the same way.

Examples

[edit]- Quadratic number fields: let be a square-free integer; then the discriminant of is[2]

- An integer that occurs as the discriminant of a quadratic number field is called a fundamental discriminant.[3]

- Cyclotomic fields: let be an integer, let be a primitive n-th root of unity, and let be the -th cyclotomic field. The discriminant of is given by[2][4]

- where is Euler's totient function, and the product in the denominator is over primes dividing .

- Power bases: In the case where the ring of algebraic integers has a power integral basis, that is, can be written as , the discriminant of is equal to the discriminant of the minimal polynomial of . To see this, one can choose the integral basis of to be

- .

- Then, the matrix in the definition is the Vandermonde matrix associated to , whose squared determinant is

- ,

- which is exactly the definition of the discriminant of the minimal polynomial.

- Let be the number field obtained by adjoining a root of the polynomial . This is Richard Dedekind's original example of a number field whose ring of integers does not possess a power basis. An integral basis is given by

- Repeated discriminants: the discriminant of a quadratic field uniquely identifies it, but this is not true, in general, for higher-degree number fields. For example, there are two non-isomorphic cubic fields of discriminant 3969. They are obtained by adjoining a root of the polynomial or , respectively.[7]

Basic results

[edit]- Brill's theorem:[8] The sign of the discriminant is where is the number of complex places of .[9]

- A prime ramifies in if and only if divides .[10][11]

- Stickelberger's theorem:[12]

- Minkowski's bound:[13] Let denote the degree of the extension and the number of complex places of , then

- Minkowski's theorem:[14] If is not , then (this follows directly from the Minkowski bound).

- Hermite–Minkowski theorem:[15] Let be a positive integer. There are only finitely many (up to isomorphisms) algebraic number fields with . Again, this follows from the Minkowski bound together with Hermite's theorem (that there are only finitely many algebraic number fields with prescribed discriminant).

History

[edit]

The definition of the discriminant of a general algebraic number field, K, was given by Dedekind in 1871.[16] At this point, he already knew the relationship between the discriminant and ramification.[17]

Hermite's theorem predates the general definition of the discriminant with Charles Hermite publishing a proof of it in 1857.[18] In 1877, Alexander von Brill determined the sign of the discriminant.[19] Leopold Kronecker first stated Minkowski's theorem in 1882,[20] though the first proof was given by Hermann Minkowski in 1891.[21] In the same year, Minkowski published his bound on the discriminant.[22] Near the end of the nineteenth century, Ludwig Stickelberger obtained his theorem on the residue of the discriminant modulo four.[23][24]

Relative discriminant

[edit]The discriminant defined above is sometimes referred to as the absolute discriminant of K to distinguish it from the relative discriminant ΔK/L of an extension of number fields K/L, which is an ideal in OL. The relative discriminant is defined in a fashion similar to the absolute discriminant, but must take into account that ideals in OL may not be principal and that there may not be an OL basis of OK. Let {σ1, ..., σn} be the set of embeddings of K into C which are the identity on L. If b1, ..., bn is any basis of K over L, let d(b1, ..., bn) be the square of the determinant of the n by n matrix whose (i,j)-entry is σi(bj). Then, the relative discriminant of K/L is the ideal generated by the d(b1, ..., bn) as {b1, ..., bn} varies over all integral bases of K/L. (i.e. bases with the property that bi ∈ OK for all i.) Alternatively, the relative discriminant of K/L is the norm of the different of K/L.[25] When L = Q, the relative discriminant ΔK/Q is the principal ideal of Z generated by the absolute discriminant ΔK . In a tower of fields K/L/F the relative discriminants are related by

where denotes relative norm.[26]

Ramification

[edit]The relative discriminant regulates the ramification data of the field extension K/L. A prime ideal p of L ramifies in K if, and only if, it divides the relative discriminant ΔK/L. An extension is unramified if, and only if, the discriminant is the unit ideal.[25] The Minkowski bound above shows that there are no non-trivial unramified extensions of Q. Fields larger than Q may have unramified extensions: for example, for any field with class number greater than one, its Hilbert class field is a non-trivial unramified extension.

Root discriminant

[edit]The root discriminant of a degree n number field K is defined by the formula

The relation between relative discriminants in a tower of fields shows that the root discriminant does not change in an unramified extension.

Asymptotic lower bounds

[edit]Given nonnegative rational numbers ρ and σ, not both 0, and a positive integer n such that the pair (r,2s) = (ρn,σn) is in Z × 2Z, let αn(ρ, σ) be the infimum of rdK as K ranges over degree n number fields with r real embeddings and 2s complex embeddings, and let α(ρ, σ) = liminfn→∞ αn(ρ, σ). Then

- ,

and the generalized Riemann hypothesis implies the stronger bound

There is also a lower bound that holds in all degrees, not just asymptotically: For totally real fields, the root discriminant is > 14, with 1229 exceptions.[29]

Asymptotic upper bounds

[edit]On the other hand, the existence of an infinite class field tower can give upper bounds on the values of α(ρ, σ). For example, the infinite class field tower over Q(√-m) with m = 3·5·7·11·19 produces fields of arbitrarily large degree with root discriminant 2√m ≈ 296.276,[28] so α(0,1) < 296.276. Using tamely ramified towers, Hajir and Maire have shown that α(1,0) < 954.3 and α(0,1) < 82.2,[27] improving upon earlier bounds of Martinet.[28][30]

Relation to other quantities

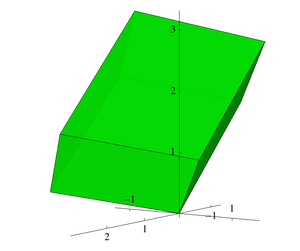

[edit]- When embedded into , the volume of the fundamental domain of OK is (sometimes a different measure is used and the volume obtained is , where r2 is the number of complex places of K).

- Due to its appearance in this volume, the discriminant also appears in the functional equation of the Dedekind zeta function of K, and hence in the analytic class number formula, and the Brauer–Siegel theorem.

- The relative discriminant of K/L is the Artin conductor of the regular representation of the Galois group of K/L. This provides a relation to the Artin conductors of the characters of the Galois group of K/L, called the conductor-discriminant formula.[31]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Cohen, Diaz y Diaz & Olivier 2002

- ^ a b Manin, Yu. I.; Panchishkin, A. A. (2007), Introduction to Modern Number Theory, Encyclopaedia of Mathematical Sciences, vol. 49 (Second ed.), p. 130, ISBN 978-3-540-20364-3, ISSN 0938-0396, Zbl 1079.11002

- ^ Definition 5.1.2 of Cohen 1993

- ^ Proposition 2.7 of Washington 1997

- ^ Dedekind 1878, pp. 30–31

- ^ Narkiewicz 2004, p. 64

- ^ Cohen 1993, Theorem 6.4.6

- ^ Koch 1997, p. 11

- ^ Lemma 2.2 of Washington 1997

- ^ Corollary III.2.12 of Neukirch 1999

- ^ Conrad, Keith. "Discriminants and ramified primes" (PDF).

Theorem 1.3 (Dedekind). For a number field K, a prime p ramifies in K if and only if p divides the integer discZ(OK)

- ^ Exercise I.2.7 of Neukirch 1999

- ^ Proposition III.2.14 of Neukirch 1999

- ^ Theorem III.2.17 of Neukirch 1999

- ^ Theorem III.2.16 of Neukirch 1999

- ^ a b Dedekind's supplement X of the second edition of Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet's Vorlesungen über Zahlentheorie (Dedekind 1871)

- ^ Bourbaki 1994

- ^ Hermite 1857.

- ^ Brill 1877.

- ^ Kronecker 1882.

- ^ Minkowski 1891a.

- ^ Minkowski 1891b.

- ^ Stickelberger 1897.

- ^ All facts in this paragraph can be found in Narkiewicz 2004, pp. 59, 81

- ^ a b Neukirch 1999, §III.2

- ^ Corollary III.2.10 of Neukirch 1999 or Proposition III.2.15 of Fröhlich & Taylor 1993

- ^ a b Hajir, Farshid; Maire, Christian (2002). "Tamely ramified towers and discriminant bounds for number fields. II". J. Symbolic Comput. 33: 415–423. doi:10.1023/A:1017537415688.

- ^ a b c Koch 1997, pp. 181–182

- ^ Voight 2008

- ^ Martinet, Jacques (1978). "Tours de corps de classes et estimations de discriminants". Inventiones Mathematicae (in French). 44: 65–73. Bibcode:1978InMat..44...65M. doi:10.1007/bf01389902. S2CID 122278145. Zbl 0369.12007.

- ^ Section 4.4 of Serre 1967

References

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Brill, Alexander von (1877), "Ueber die Discriminante", Mathematische Annalen, 12 (1): 87–89, doi:10.1007/BF01442468, JFM 09.0059.02, MR 1509928, S2CID 120947279, retrieved 2009-08-22

- Dedekind, Richard (1871), Vorlesungen über Zahlentheorie von P.G. Lejeune Dirichlet (2 ed.), Vieweg, retrieved 2009-08-05

- Dedekind, Richard (1878), "Über den Zusammenhang zwischen der Theorie der Ideale und der Theorie der höheren Congruenzen", Abhandlungen der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, 23 (1), retrieved 2009-08-20

- Hermite, Charles (1857), "Extrait d'une lettre de M. C. Hermite à M. Borchardt sur le nombre limité d'irrationalités auxquelles se réduisent les racines des équations à coefficients entiers complexes d'un degré et d'un discriminant donnés", Crelle's Journal, 1857 (53): 182–192, doi:10.1515/crll.1857.53.182, S2CID 120694650, retrieved 2009-08-20

- Kronecker, Leopold (1882), "Grundzüge einer arithmetischen Theorie der algebraischen Grössen", Crelle's Journal, 92: 1–122, JFM 14.0038.02, retrieved 2009-08-20

- Minkowski, Hermann (1891a), "Ueber die positiven quadratischen Formen und über kettenbruchähnliche Algorithmen", Crelle's Journal, 1891 (107): 278–297, doi:10.1515/crll.1891.107.278, JFM 23.0212.01, retrieved 2009-08-20

- Minkowski, Hermann (1891b), "Théorèmes d'arithmétiques", Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences, 112: 209–212, JFM 23.0214.01

- Stickelberger, Ludwig (1897), "Über eine neue Eigenschaft der Diskriminanten algebraischer Zahlkörper", Proceedings of the First International Congress of Mathematicians, Zürich, pp. 182–193, JFM 29.0172.03

Secondary sources

[edit]- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1994). Elements of the history of mathematics. Translated by Meldrum, John. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-64767-6. MR 1290116.

- Cohen, Henri (1993), A Course in Computational Algebraic Number Theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 138, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-55640-4, MR 1228206

- Cohen, Henri; Diaz y Diaz, Francisco; Olivier, Michel (2002), "A Survey of Discriminant Counting", in Fieker, Claus; Kohel, David R. (eds.), Algorithmic Number Theory, Proceedings, 5th International Syposium, ANTS-V, University of Sydney, July 2002, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 2369, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, pp. 80–94, doi:10.1007/3-540-45455-1_7, ISBN 978-3-540-43863-2, ISSN 0302-9743, MR 2041075

- Fröhlich, Albrecht; Taylor, Martin (1993), Algebraic number theory, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, vol. 27, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-43834-6, MR 1215934

- Koch, Helmut (1997), Algebraic Number Theory, Encycl. Math. Sci., vol. 62 (2nd printing of 1st ed.), Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-63003-1, Zbl 0819.11044

- Narkiewicz, Władysław (2004), Elementary and analytic theory of algebraic numbers, Springer Monographs in Mathematics (3 ed.), Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-21902-6, MR 2078267

- Neukirch, Jürgen (1999). Algebraische Zahlentheorie. Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften. Vol. 322. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-65399-8. MR 1697859. Zbl 0956.11021.

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (1967), "Local class field theory", in Cassels, J. W. S.; Fröhlich, Albrecht (eds.), Algebraic Number Theory, Proceedings of an instructional conference at the University of Sussex, Brighton, 1965, London: Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-163251-2, MR 0220701

- Voight, John (2008), "Enumeration of totally real number fields of bounded root discriminant", in van der Poorten, Alfred J.; Stein, Andreas (eds.), Algorithmic number theory. Proceedings, 8th International Symposium, ANTS-VIII, Banff, Canada, May 2008, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 5011, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, pp. 268–281, arXiv:0802.0194, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-79456-1_18, ISBN 978-3-540-79455-4, MR 2467853, S2CID 30036220, Zbl 1205.11125

- Washington, Lawrence (1997), Introduction to Cyclotomic Fields, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 83 (2 nd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-94762-4, MR 1421575, Zbl 0966.11047

Further reading

[edit]- Milne, James S. (1998), Algebraic Number Theory, retrieved 2008-08-20

![{\displaystyle {\mathcal {O}}_{K}=\mathbb {Z} [\alpha ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/31005efc0de497a687d765cbf9805b49763adcc1)

![{\displaystyle \Delta _{K/F}={\mathcal {N}}_{L/F}\left({\Delta _{K/L}}\right)\Delta _{L/F}^{[K:L]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7f9f1950d56e6b263c691d3bb2178876560680aa)