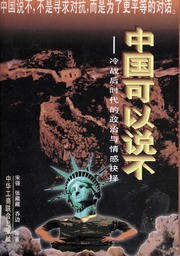

China Can Say No

First edition | |

| Author |

|

|---|---|

| Published | 1996 |

| Publisher | China Federation of Literary and Art Circles Publishing (中国文联出版社) |

| Publication place | China |

| ISBN | 7505925458 |

| OCLC | 953046578 |

| Chinese name | |

| Simplified Chinese | 《中国可以说不:冷战后时代的政治与情感抉择》 |

| Traditional Chinese | 《中國可以說不:冷戰後時代的政治與情感抉擇》 |

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhōngguó kěyǐ shuō bù: Lěngzhànhòu shídài de zhèngzhì yǔ qínggǎn juézé |

China Can Say No (中国可以说不) is a 1996 Chinese language non-fiction manifesto written and edited by Song Qiang, Zhang Zangzang (whose original name is Zhang Xiaobo), Qiao Bian, Tang Zhengyu, and Gu Qingsheng. It was published in China and strongly expresses Chinese nationalism. Its full title is often translated as The China That Can Say No: Political and Emotional Choices in the post Cold-War era. It became an overnight bestseller, as the authors called on the Beijing government to stand up against the United States in a new era of global competition. In addition the book bashes Japan for defection from Asia in favor of an American connection. The popularity indicates the growth of anti-American and anti-Japanese sentiment in the Chinese public. It indicates disillusionment among many younger and better educated Chinese as the nation searches for a major role in the global economic and political systems. The Beijing government originally endorsed the general thesis, but after sharp criticism from the United States and Asia, the government condemned the book as an irresponsible source of confusion, and banned it from circulation.[1]

Background

[edit]Context

[edit]At the time the book was published, the Chinese government, intellectuals, and the general public were becoming increasingly hostile towards what they viewed as unfair treatment by the United States and efforts by the US to isolate China.[2]: 212 Factors contributing to this dissatisfaction included trade friction between the US and China, US complaints about human rights in China, and continued US support for Taiwan.[2]: 212

In the early 1990s, a trend in Chinese publishing was increased demand for political treatises and commentaries, including on foreign policy issues.[2]: 226

China Can Say No is inspired by Japanese Nationalist politician Shintaro Isihara's 1989 essay, The Japan That Can Say No.[2]: 240

Authors

[edit]Publisher Zhang recruited four co-authors to write a book that would appeal to growing nationalist sentiment.[2]: 227 These were Song Qiang (a college friend of Zhang's who was working as an advertising manager in Chongqing), Qiao Bian (a gardener at the Beijing Gardening and Greening Bureau), Gu Qingsheng (a Beijing-based freelance writer), and Tang Zhengyu (a reporter from the China Business Times).[2]: 227

Zhang is a former student radical and "uncritical admirer of all things American". His disillusionment with foreign countries' treatment of China, and particularly that by America, reflects the experience of about a quarter of Chinese students studying in the United States, who, despite their initial Americophilia, undergo a surge of Chinese patriotism upon their return. Contributing factors to this transformation in the United States include racial discrimination, denial of cultural legitimacy, and negative media portrayal.[3]

Most of the authors came from modest backgrounds and had no connection to either the Chinese government or its liberal opponents.[2]: 225 The authors described themselves as "wild-grass intellectuals" who represented the common people.[2]: 227

Contents

[edit]The book argues that many fourth-generation Chinese embraced Western values too strongly in the 1980s and disregarded their heritage and background.

The book specifically criticizes a number of activists such as physicist Fang Lizhi and journalist Liu Binyan.[citation needed]

Describing a disenchantment among Chinese with the US starting in the 1990s, especially after it adopted a supposed containment policy, rejected China's bid for the World Trade Organization, and worked against China's bid for the 2000 Summer Olympics, the authors criticize US foreign policy (in particular, support for Taiwan) and American individualism. The authors contend that China is surrounded by hostile forces and that the United States seeks to undermine China through cultural and political means, such as through Voice of America, and through American espionage in China.[2]: 230 The authors regard the Third Taiwan Strait crisis as reflecting the hypocrisy of the United States, characterizing US foreign policy as mendacious and veiled with the language of universal human rights.[2]: 212

The book deplores unfair treatment of China by the US (as symbolized by the Yinhe incident of 1993). It claims that China is used as a scapegoat for American problems and voices support for such governments as that of Fidel Castro's Cuba which openly declare their opposition to the US. The book advocates for the Chinese people to say no to unjust demands.[2]: 212

The book also focuses on Japan. It describes Japan of being a client state of the US, contends that Japan should not get a seat on the United Nations Security Council, and supports a renewed call for war reparations to China from Japan for its actions in the Second Sino-Japanese War.[citation needed]

Song Qiang's section of the book, The Death of Heaven's Mandate and the Coming of a New Order, is an autobiographical account of Song's development from a naïve pro-American student to a Chinese patriot.[2]: 228

The next section, Be a Chinese: The Emotional and Political Choices in the Post-Cold War Era, characterizes the US as carrying out a "cultural invasion" of China to destroy it through peaceful evolution theory.[2]: 228–229

In the section Abandon Fantasy and Prepare for Future Struggle, the authors seek to create a sense of national preservation in the reader by imagining a future in which a disintegrating China consists of central areas in Hebei and Henan, surrounded by independent regional powers in the form of a Kingdom of Tibet, an East Turkestan state, a Greater Mongolian Nation, a reinstalled Manchukuo regime, and an expanded and independent Taiwan.[2]: 230–232

Impact

[edit]The first 50,000 copies sold out on the day of release and an additional 100,000 copies sold within one month.[2]: 212 The book resulted in a public Say No enthusiasm and a number of domestic media outlets described it as a triumph of the people.[2]: 242–243 Outlets praising the book often used the term minjian (which can be variously translated in English, including as "among the people" and "folk") to characterize the authors as anti-establishment figures motivated by a genuine patriotic sentiment.[2]: 243

China Can Say No inspired the state-run Chinese Academy of Social Science to publish the book Behind the Demonization of China.[2]: 245 In Behind the Demonization of China, Chinese scholars and journalists wrote about their experiences with Sinophobia during their time in the United States.[2]: 245

Several official media outlets criticized the book in an effort to dampen public Say No enthusiasm.[2]: 242 Beijing Legal News carried a front-page article Dialogue is Better than Confrontation, which opposed the confrontational nature of Say No rhetoric and cited Jiang Zemin's advocacy for peaceful and rational dialogue with the United States.[2]: 242 Chinese Academy of Social Science fellow Shen Jiru published a book length response to China Can Say No contending that the Say No authors had a "Red Guard mentality" and disregarded the norms of mutual understanding and strategic cooperation in the age of multilateralism.[2]: 242–243

Chinese liberals regarded the book as a scandal.[2]: 244 For example, essayist Wang Xiaobo wrote a satirical review of the book.[2]: 244

Total sales are estimated at one million to two million copies.[2]: 212 A best-seller in China, the book became a benchmark for 1990s nationalist sentiment.[4] It has been translated into eight languages.[2]: 212 A Japanese translation by Mo Bangfu and Suzuki Kaori was published in 1996 by Nikkei.[5]

Sequel

[edit]A series of Say No sequels followed, including How China can Say No, Why China Can Say No, and China Can Still Say No.[2]: 212–213

In 2009, Unhappy China, a follow-up version, was published.

References

[edit]- ^ Yuwu Song, ed., Encyclopedia of Chinese-American Relations (McFarland, 2009) pp 56-57.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Tu, Hang (2025). Sentimental Republic: Chinese Intellectuals and the Maoist Past. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 9780674297579.

- ^ Guo, Xiaoqin (2003). State and Society in Chinas Democratic Transition: Confucianism, Leninism, and Economic Development. Psychology Press. pp. 87–88. doi:10.4324/9780203497357. ISBN 978-1-135-94418-6.

- ^ Wang, Frances Yaping (2024). The Art of State Persuasion: China's Strategic Use of Media in Interstate Disputes. Oxford University Press. p. 69. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197757505.001.0001. ISBN 9780197757512.

- ^ 『ノーと言える中国』. 日本経済新聞社. 1996. ISBN 4532145198. OCLC 43464914.