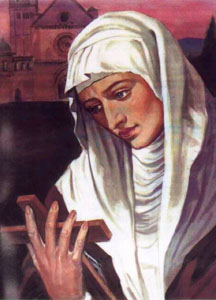

Agnes of Assisi

Agnes of Assisi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Virgin | |

| Born | 1197 or 1198 Assisi, Italy |

| Died | 16 November 1253 Assisi, Italy |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholicism Order of St. Clare |

| Canonized | cultus confirmed 1753 by Pope Benedict XIV |

| Major shrine | Basilica of St. Clare Assisi, Italy |

| Feast | 16 November |

| Attributes | Poor Clare nun holding a book |

Agnes of Assisi was born between 1197-1198 in Assisi, Italy, and was one of the founding members of the Order of the Poor Ladies (The Poor Clares). Agnes eventually established the convent of Monticelli near Florence in 1219, then went on to Verona, Padua, Venice, and Mantua between 1224 and 1238.

Life

[edit]Agnes (born Caterina) and her sisters, Clare and Beatrix, were daughters of a nobleman, Count Favorino Scifi. Agnes's childhood was spent between her father's home in the city as well as his castle of Sasso Rosso on Mount Subasio with her sisters and her mother, Blessed Hortulana.

On 18 March 1212, Agnes’s eldest sister Clare, inspired by the example of Francis of Assisi, left their father's home in secret to become a follower of Francis. Sixteen days later, moved by her desire to live like Christ, Agnes ran off to the Church of St. Angelo di Panzo where Francis had brought her sister, resolved to share Clare's life of poverty and penance.

Angry at the loss of two of his daughters to the convent, their father sent his brother Monaldo and eleven other relatives and armed followers to the monastery to attempt to bring Agnes home and be wed. Agnes refused their demands, and the men began to ambush her, attempting to drag her from the church while striking and kicking her repeatedly. Her body suddenly became so heavy that the men could not lift her from the ground. This infuriated her uncle, Monaldo, who drew his sword to strike his niece. At that moment, his arm allegedly dropped to his side, withered and useless. Agnes's relatives, realizing that something divine protected her, allowed her to remain with Clare and live a life of celibacy.

Francis later established a cloister for Clare and Agnes at the rural chapel of San Damiano. They were soon joined by other noblewomen of the city, and the Order of Poor Ladies, later known as the Poor Clares, began, with Clare as its abbess. In 1221, a group of Benedictine nuns in Monticelli near Florence asked to become Poor Ladies. Despite being young, Agnes was chosen to lead the new community. As an abbess, Agnes was extremely loving, kind, and clever. Agnes knew how to make the practice of virtue bright and attractive to her subjects. Although life in the Florentine convent was harmonious and without faction, she missed her sister greatly.

In 1253, Agnes returned to Assisi to nurse her sister Clare during the latter's illness. Shortly thereafter Agnes died, on 16 November 1253. Her remains were interred with those of her sister at the Basilica of St. Clare at Assisi.

Agnes's feast day is the anniversary of her death, 16 November. She was canonized in 1753, 500 years later, by Pope Benedict XIV.

Historiography

[edit]Not much scholarship exists detailing the life of Agnes of Assisi. There are many reasons why this happened, but historians are slowly writing more about nuns in the thirteenth century.

In early scholarship, Clare, Agnes, and other Franciscan nuns are missing. The arguments of historians before 1953 say little to nothing about these women and instead focus on the power that Francis himself had in reforming the church. Victor G. Green’s journal article about Franciscans, published in 1939, includes almost nothing about Clare, let alone her lesser known sister. When he does mention Clare, she is only named for her order and as a simple follower of Francis, not the profoundly spiritual individual she was. Although this is a history of the Franciscan movement in England, far away from Italy where Clare and Francis both lived, Green does get into the history of church reform. He hails the monumental leaders of church reform as Francis and Dominic. Clare’s order is mentioned only briefly in a few places within the 172-page article. His argument about how significant the Franciscan movement is almost entirely leaves out the women that were involved. Other sources from this time are similar, only examining the Franciscan movement with regard to monks and brotherhoods.

Living most of her life in Assisi, Italy, Gemma Fortini was an accomplished journalist and historian. In 1982, she published “The Noble Family of St. Clare of Assisi” with the help of Finbarr Conroy in translating the work to English. Fortini argues that Saint Clare of Assisi was mainly influential due to her familial connections, her socio-economic status, and the popularity of Saint Francis. As the political landscape evolved, the noble families desired a change, one which they found in the teachings of Saint Francis, as his teachings encouraged all to give up worldly possessions in favor of Christ-like poverty. Saint Clare’s following consisted primarily of women of nobility, including her two sisters, her mother, and two of her nieces, all of whom sought out a holy escape from the social upheaval sweeping through the nobility. According to Fortini, the Order of the Poor Ladies that Saint Clare founded was merely the female version of the Franciscan Order and would not have existed without the work of and general respect toward Saint Francis. Saint Clare used her family connections to other nobility and the papacy to gain respect for her teachings, these connections helped her avoid accusations of heresy and spread her message to a greater population than would have otherwise been possible for a woman at the time.

Jacques Dalarun, a French historian and author, published “Francis and Clare of Assisi: Differing Perspectives on Gender and Power” in 2005. In this article, he rejects the notion that there was any love story involved in Saint Clare of Assisi’s development of the Poor Ladies of San Damiano. The idea of a romantic relationship growing between Saint Clare and Saint Francis has previously been used to diminish the role of Saint Clare, Saint Agnes of Assisi, and the other important women involved in the development of the Franciscan Order. Dalarun argues that due to the chivalrous nature of the society surrounding him, Saint Francis likely viewed women as more like prey than men and therefore not his equals; however, he points out that this view of women appears to shift as Saint Francis digs deeper into his faith. Although it does not seem that Saint Francis ever adopts an egalitarian view of women, as he states a belief that the greatest threat to the religious life of men is interaction with women. As a woman with her own teachings on Christianity, Saint Clare was both admired and detested by the papacy as she did not fit into the assigned box she was supposed to adhere to as a woman, but at same time she served as a good role model for those women pursuing religious livelihoods of their own. Saint Clare did not desire closeness with Francis or the Pope but rather with Christ himself. It was this desire that drove her to form and share her teachings, and it was this desire for Christ that pulled other women in to follow her teachings. Saint Clare chose to ignore gender in her religious rules, choosing to see Christ in everyone around her, especially the poor as she viewed poverty as the only way to truly imitate the life of Christ.

In Cristina Andenna’s “Female Religious Life in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries”, there is no mention of Agnes and her contributions. The text states how Clare of Assisi was an excellent example of how women had problems when it came to women attempting to enter a community of religious faith. Clare was apparently fascinated by Saint Francis's message and the work that he was doing through his faith. Clare eventually settled with a small group of women in the monastery of San Damiano near Assisi, who lived in the Franciscan ideal of poverty with the support of Francis and his several male followers. According to the text, “The Franciscan concept of evangelical radical poverty, considered dangerous by the Roman Curia, was particularly controversial for female communities. It was thus not long before San Damiano was steered in a more traditional direction and Clare was made abbess of her community”(1051).

While this source is extremely useful and depicts Clare’s journey, there is no mention of her sister, despite Agnes being a prominent member of the faith and the spread of Franciscans throughout Italy. Agnes is once again overshadowed by her sister despite having similar roles and experiences as members of the Franciscans and eventually the Order of the Poor Ladies. It is almost as if Agnes did not even exist or was not prominent enough to report.

Another secondary source, “Catholic Encyclopedia” proves this point within the first sentence of Agnes of Assisi’s biography. The text states, “Younger sister of St. Clare and Abbess of the Poor Ladies, born at Assisi, 1197, or 1198; died 1253. She was the younger daughter of Count Favorino Scifi. Her saintly mother, Blessed Hortulana, belonged to the noble family of the Fiumi, and her cousin Rufino was one of the celebrated "Three Companions" of St. Francis”(Robinson). While it can be inferred that this is important for context, it once again insinuates that she was only recognizable through her lineage and their accomplishments. The text goes on to explain that Agnes's childhood was spent between her father's home in the city as well as his castle of Sasso Rosso on Mount Subasio. According to the text, “On 18 March 1212, her eldest sister Clare, moved by the preaching and example of St. Francis, left her father's home to follow the way of life taught by the Saint. Sixteen days later, Agnes repaired to the monastery of St. Angelo in Panso, where the Benedictine nuns had afforded Clare temporary shelter, and resolved to share her sister's life of poverty and penance”. Once again, turning the focus back to Clare.

The text goes on to state how as an abbess, Agnes was extremely loving, kind, and clever. Agnes knew how to make the practice of virtue bright and attractive to her subjects. Despite being young at the time Agnes was chosen by St. Francis to found and govern a community of the Poor Ladies at Monticelli, near Florence, which over time became turned into The Order of the Poor Ladies after several women were moved by the work of Agnes and Clare. A letter written by St. Agnes to Clare after this separation is still extant, touchingly beautiful in its simplicity and affection. However, the text also states, “Nothing perhaps in Agnes's character is more striking and attractive than her loving fidelity to Clare's ideals and her undying loyalty to upholding the latter in her lifelong and arduous struggle for Seraphic Poverty”. Again, this is important for understanding the historical context and who Agnes was as an individual, but it seems that this source like the others circles back to Clare.

The most recent scholarship devoted to Franciscans has shifted in opinion. Instead of followers devoted to Francis and nothing more, historians have begun to give Clare credit for starting a movement. They include the women that became a part of her order and see them as equal members of the movement. Although I could not find a way to access the document, Jaques Dalarun, in his 2005 article gives credit to Ignatius Brady starting this shift through both writing and speaking. Different sources have different opinions on when this shift exactly started, but it has, and it is seeping into current texts. Dalarun, for example, acknowledges that Clare and Agnes, along with their impact on the Franciscan movement, have been missing from scholarship for so long. Dalarun argues that Francis turned social and gender norms over, while Clare ignored them. He also argues that their thoughts on poverty were different! After so many authors marked Clare as only a follower of Francis, Dalarun claims that for Francis, poverty was a pathway to God, while for Clare it was a way to live in God’s nature.

Notes

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Robinson, Paschal (1907). "St. Agnes of Assisi". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Robinson, Paschal (1907). "St. Agnes of Assisi". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

References

[edit]- Andenna, Cristina. 2020. "Female Religious Life in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries." In The Cambridge History of Medieval Monasticism in the Latin West, edited by Allison I. Beach and Isabelle Cochelin.

- Arnald of Sarrant. 1374. Chronicle of the Twenty Four-Generals of The Order of Friars Minor. Translated by Noel Muscat.

- Bartoli, Marco. Chiara d'Assisi. Rome 1989: Instituto Storico dei Cappucini.

- Conroy, Finbarr, and Gemma Fortini. 1982. "The Noble Family of St. Clare of Assisi." Franciscan Studies 42: 48-67.

- Dalarun, Jaques. 2005. "Frances and Clare of Assisi: Differing Perspectives on Gender and Power." Franciscan Studies 63: 11-25.

- Green, Victor G. 1939. "The Franciscans in Medieval English Life (1224 - 1348)." Franciscan Studies 20: V-XI, 1-164.

- Robinson, Paschal. 1907. "St. Agnes of Assisi." In The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

- "Agnes of Assisi", Saints Resource, RCL Benziger

- Foley, Leonard. "St. Agnes of Assisi", Saint of the Day, Franciscan Media

- People from Assisi

- 1190s births

- 1253 deaths

- 13th-century Christian saints

- 13th-century Italian Roman Catholic religious sisters and nuns

- Medieval Italian saints

- Poor Clare abbesses

- Franciscan saints

- Italian Roman Catholic abbesses

- Italian Roman Catholic saints

- Female saints of medieval Italy

- Canonizations by Pope Benedict XIV