Acetamiprid

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

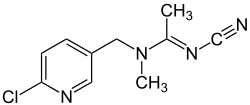

| IUPAC name

N-[(6-chloro-3-pyridyl)methyl]-N'-cyano-N-methyl-acetamidine

| |

| Other names

(1E)-N-[(6-Chlor-3-pyridinyl)methyl]-N'-cyan-N-methylethanimidamid;

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.111.622 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | acetamiprid |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H11ClN4 | |

| Molar mass | 222.678 |

| Appearance | white powder |

| Density | 1.17 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 98.9 °C (210.0 °F; 372.0 K) |

| Hazards | |

| Flash point | 166.9 °C (332.4 °F; 440.0 K) |

| Pharmacology | |

| Legal status |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Acetamiprid is an organic compound with the chemical formula C10H11ClN4. It is an odorless neonicotinoid insecticide produced under the trade names Assail, and Chipco by Aventis CropSciences. It is systemic and intended to kill sucking insects (Thysanoptera, Hemiptera, mainly aphids[1]) on crops such as leafy vegetables, citrus fruits, pome fruits, grapes, cotton, cole crops, and ornamental plants. It is also a key pesticide in commercial cherry farming due to its effectiveness against the larvae of the cherry fruit fly.

Acetamiprid belongs to the family of chloropyridinyl neonicotinoid insecticides introduced in the early 1990s.[2] It is also used for controlling domestic pests (such as fleas on cats and dogs).

Structure and reactivity

[edit]Acetamiprid is an α-chloro-N-heteroaromatic compound. It is a neonicotinoid with a chloropyridinyl group and it is comparable to other neonicotinoids such as imidacloprid, nitenpyram and thiacloprid. These substances all have a 6-chloro-3-pyridine methyl group but differ in the nitroguanidine, nitromethylene, or cyanoamidine substituent on an acyclic or cyclic moiety.[3]

There are two isomeric forms in acetamiprid with E and Z-configurations of the cyanoimino group. There are also a variety of stable conformers due to the rotation of single bonds in the N-pyridylmethylamino group. The E-conformer is more stable than the Z-conformer and assumed to be the active form. In solution, two different E-conformers exist which slowly change into each other.[4]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Acetamiprid is a nicotine-like substance and reacts to the body in a similar way as nicotine.[5]

Metabolism

[edit]The metabolism of acetamiprid has been primarily studied in plants and soil. However, a recent study (2005) focussed on the metabolism of acetamiprid in honey bees. The honey bees in this study were fed a sucrose solution that contained acetamiprid. Seven different metabolites were discovered, of which two could not be identified. The five most abundant of these metabolites were found in the abdomen of the bee. Within the first hour of ingestion, acetamiprid concentrations were highest in tissues with a high nicotinic acetylcholine receptor density such as the abdomen, thorax and head.[2]

Acetamiprid was rapidly distributed throughout the bee's body, but also rapidly metabolised into the seven compounds. The substance is not just broken down in the gut, but in the entire body of the bee. This is mainly done by Type I enzymes such as mixed function oxidases. These enzymes use O2 to catalyze a reaction and convert acetamiprid into more polar metabolites. This makes it easier to excrete the compounds because the compounds become more hydrophilic.[2] Phase I enzymes form the first step in metabolizing the compound. Phase I metabolites can be bioactive.[6]

Three metabolic pathways exist, based on the kinetics of the metabolites that were found. The first pathway starts with the oxidative cleavage of the nitromethylene bond of acetamiprid. This is followed by another oxidation that forms 6-chloronicotinic acid. 6-Chloronicotinic acid is then transformed in one of the unidentified compounds, with an increased polarity. The second possible pathway is based on N-demethylation reactions, followed by oxidation of the nitromethylene bond of the intermediates. This will also result in 6-chloronicotinic acid.[2]

The last pathway consists of the oxidative cleavage of the cyanamine group. In this reaction a 1-3 ketone derivative is formed. This compound will undergo N-deacetylation which forms a 1-4 ketone derivative. This compound is transformed by oxidative cleavage into 6-chloropicolyl alcohol. From here, the compound can be metabolized in two different ways: either it is oxidized into 6-chloronicotinic acid or it is converted into a glycoconjugate derivative. The latter is probably in favour of the oxidization.[2]

Efficacy and side effects

[edit]Efficacy

[edit]Acetamiprid is used to protect a variety of crops, plants and flowers. It can be used combined with another pesticide with a different mode of action. This way the developing of resistance by pest species can be prevented. According to the US EPA acetamiprid could play a role in battling resistance in the species: Bemisia, greenhouse whiteflies and western flower thrips.[7]

Neonicotinoids act as agonists for nAChR (Nicotinic AcetylCholine Receptor, receptor polypeptides that respond to the neurotransmitter acetylcholine), and are selectively toxic to insects versus mammals, because of a higher potency on insect than mammalian nAChRs.[3] This increases their suitability as pesticides.

Adverse effects

[edit]Acetamiprid has a high potential for bioaccumulation and is highly toxic to birds and moderately toxic to aquatic organisms.[8] Excessive use of the pesticide could pose a threat to bird populations and other parts of the food chain. On the other hand, the metabolites that are produced after the absorption of acetamiprid in the honey bee are less toxic than those of other neonicotinoides. The half-life time of acetamiprid is also rather short, approximately 25–30 minutes, whereas other neonicotinoides can have a half-life of 4–5 hours. However, some metabolites are still present in the honey bee after 72 hours. This might be a toxicological risk for honey bees, as chronic exposure can increase the toxicity of certain compounds.[2] The EPA considers it "only moderately toxic" to bees; however, some media sources and the recent documentary Vanishing of the Bees have blamed neonicotinoids like acetamiprid for colony collapse disorder.

According to a report of the EPA from 2002, acetamiprid poses low risks to the environment compared to other insecticides. It degrades rapidly in soil and has therefore a low chance of leaching into groundwater. The degradation products will be able to reach the groundwater but are predicted to not be of toxicological significance.[9]

Toxicity

[edit]Insect studies

[edit]German scientists showed that spraying acetamiprid on a grassland — at low concentrations similar to those found at the edges of treated fields — led, in just two days, to a 92% collapse in the populations of the three most abundant insect species in these environments. This corresponds to a sensitivity to acetamiprid more than 11,000 times greater than that of the honeybee.[10]

Extensive studies in the honeybee showed that acetamiprid LD50 is 7.1 μg with a 95% confidence interval of 4.57-11.2 μg per bee. In comparison, the LD50 of imidacloprid is 17.9 ng per bee. The difference in these comparable substances may be explained by a slightly weaker affinity of acetamiprid for nAChr when compared with imidacloprid.[11]

Neonicotinoids with a nitroguanidine group, such as imidacloprid, are most toxic to honey bees. Acetamiprid has an acyclic group instead of a second heterocyclic ring and is therefore much less toxic to honey bees than nitro-substituted compounds.[12]

Data on pollinators are incomplete. The acute toxicity of acetamiprid to the honeybee (Apis mellifera) is indeed about a thousand times lower than that of most other neonicotinoids. However, as EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) points out, the studies submitted by the industry to test the product under real-life conditions raised "concerns regarding their robustness and reliability due to serious shortcomings."[13][14]

Humans

[edit]An EFSA ( European Food Safety Authority) report indicates that exposure to the neonicotinoid is associated with a decrease in testosterone levels — a result observed not only in laboratory mice, but also across all categories of a representative sample of the U.S. population. These findings suggest endocrine-disrupting properties — properties that "should be assessed," writes EFSA, according to the regulatory standards adopted in 2018. This has not been done.[15][16]

Chinese research published on May 10 2025 examined 144 adults suffering from neurological disorders and compared their exposure to neonicotinoids with that of 30 healthy individuals. The authors report that exposure to these neurotoxic substances and their metabolites is associated with markers of inflammation, and that the main metabolite of acetamiprid is, among all the compounds analyzed, the most prevalent in the samples. Most notably, they show that the average urinary levels of acetamiprid are six to seven times higher in the affected individuals than in the healthy ones.[17]

Chinese researchers have shown that, among more than 300 volunteers of all ages recruited for their study, over 85% had detectable traces of the main metabolite of acetamiprid in their cerebrospinal fluid. EFSA also determined that the current maximum residue limits in fruits and vegetables posed a risk to consumers.[18]

As of now, two human case-studies have been described with acute poisoning by ingestion of an insecticide mixture containing acetamiprid whilst trying to commit suicide. Both patients were transported to an emergency room within two hours, and were instantly experiencing nausea, muscle weakness, convulsions and low body temperature (33.7 °C and 34.3 °C respectively). Symptoms such as muscle weakness seem to be similar to organophosphate insecticide exposure. Hypothermia and convulsions can be directly explained by the active acetamiprid compound which react with acetylcholine- and nicotinic receptors. Although mammalian toxicity is recorded as low, high doses of acetamiprid are recorded to be toxic to humans.[19]

Mammals

[edit]Studies (in Europe, China, and Japan) have established a link between acetamiprid and neurodevelopmental disorders in mammals. In a statement from May 2024, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) stated that "there are major uncertainties for the developmental neurotoxicity properties (toxicity affecting brain development) of acetamiprid and, therefore, further data are needed to achieve a more robust mechanistic understanding that would enable a proper hazard and risk assessment."[20][21]

In February 2025, Japanese researchers demonstrated that laboratory rodents exposed in utero to low doses of acetamiprid showed alterations in the structure of their cerebellum, and at higher doses, suffered motor disorders. In May 2011, Jiao-jiao Zhang and colleagues concluded that acetamiprid damages the male reproductive function of male Kunming mice by inducing oxidative stress in the testes.[22]

Safety indications

[edit]In Europe Acetamiprid is not considered persistent in soil but persistent in water. It is considered highly toxic for aquatic organisms. [23] [24] [25]

In United States, Acetamiprid is classified as unlikely to be a human carcinogen by EPA. Acetamiprid has an uncertain acute and chronic toxicity in mammals. It is classified as toxicity category rating II in acute oral studies with rats, toxicity category III in acute dermal and inhalation studies with rats, and toxicity category IV in primary eye and skin irritation studies with rabbits. It is mobile in soil, but degrades rapidly via aerobic soil metabolism, with studies showing its half-life between <1 and 8.2 days. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) does not consider it to be environmentally persistent.

A recent study has implicated acetamiprid as a cause of erectile dysfunction in human males and may be implicated in the problem of declining human fertility, and called into question its safety, particularly where its use may be subject to abuse.[26]

To ensure that application rates do not exceed limits which may be toxic to non-target vertebrates, the US proposes a maximum application rate of 0.1 to 0.6 pounds per acre (0.11 to 0.67 kg/ha) of active ingredient per season of agricultural land, differentiating between different crop types.[27] In China, the maximum dose is lower than in the US. The recommended dose that is used in agriculture ranges from 0.055 to 0.17 pounds of active ingredient per acre.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Yao, Xiao-hua; Min, Hang; Lü, Zhen-hua; Yuan, Hai-ping (April 2006). "Influence of acetamiprid on soil enzymatic activities and respiration". European Journal of Soil Biology. 42 (2): 120–126. Bibcode:2006EJSB...42..120Y. doi:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2005.12.001.

- ^ a b c d e f Brunet, Jean-Luc; Badiou, Alexandra; Belzunces, Luc P (August 2005). "In vivo metabolic fate of [ 14 C]-acetamiprid in six biological compartments of the honeybee, Apis mellifera L". Pest Management Science. 61 (8): 742–748. Bibcode:2005PMSci..61..742B. doi:10.1002/ps.1046. PMID 15880574.

- ^ a b Ford, Kevin A.; Casida, John E. (July 2006). "Chloropyridinyl Neonicotinoid Insecticides: Diverse Molecular Substituents Contribute to Facile Metabolism in Mice". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 19 (7): 944–951. doi:10.1021/tx0600696. PMID 16841963.

- ^ Nakayama, Akira; Sukekawa, Masayuki; Eguchi, Yoshiyuki (October 1997). "Stereochemistry and active conformation of a novel insecticide, acetamiprid". Pesticide Science. 51 (2): 157–164. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-9063(199710)51:2<157::aid-ps620>3.0.co;2-c.

- ^ Kimura-Kuroda, Junko; Komuta, Yukari; Kuroda, Yoichiro; Hayashi, Masaharu; Kawano, Hitoshi (29 February 2012). "Nicotine-Like Effects of the Neonicotinoid Insecticides Acetamiprid and Imidacloprid on Cerebellar Neurons from Neonatal Rats". PLOS ONE. 7 (2): e32432. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732432K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032432. PMC 3290564. PMID 22393406.

- ^ Casida, John E. (13 April 2011). "Neonicotinoid Metabolism: Compounds, Substituents, Pathways, Enzymes, Organisms, and Relevance". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 59 (7): 2923–2931. Bibcode:2011JAFC...59.2923C. doi:10.1021/jf102438c. PMID 20731358.

- ^ US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Pesticide Programs. (2010). Response Letter for Extension of the Exclusive Use Data Protection Period for Acetamiprid and Acetamiprid Technical.

- ^ University of Hertfordshire. (2018). Pesticide Properties DataBase. "acetamiprid". Retrieved from: [1] Archived 2018-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ US Environmental Protection Agency. (2002). Pesticide Fact Sheet: Acetamiprid.

- ^ Sedlmeier, Jan Erik; Grass, Ingo; Bendalam, Prasanth; Höglinger, Birgit; Walker, Frank; Gerhard, Daniel; Piepho, Hans-Peter; Brühl, Carsten A.; Petschenka, Georg (18 March 2025). "Neonicotinoid insecticides can pose a severe threat to grassland plant bug communities". Communications Earth & Environment. 6 (1) 162. Bibcode:2025ComEE...6..162S. doi:10.1038/s43247-025-02065-y.

- ^ Tomizawa, Motohiro; Casida, John E. (January 2003). "Selective Toxicity of Neonicotinoids Attributable to Specificity of Insect and Mammalian Nicotinic Receptors". Annual Review of Entomology. 48 (1): 339–364. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112731. PMID 12208819.

- ^ Iwasa, Takao; Motoyama, Naoki; Ambrose, John T.; Roe, R.Michael (May 2004). "Mechanism for the differential toxicity of neonicotinoid insecticides in the honey bee, Apis mellifera". Crop Protection. 23 (5): 371–378. Bibcode:2004CrPro..23..371I. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2003.08.018.

- ^ "Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance acetamiprid". EFSA Journal. 14 (11). November 2016. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4610.

- ^ Shi, Jingliang; Wang, Xiaolong; Luo, Yi (March 2025). "Honey bees prefer moderate sublethal concentrations of acetamiprid and experience increased mortality". Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 208 106320. Bibcode:2025PBioP.20806320S. doi:10.1016/j.pestbp.2025.106320. PMID 40015911.

- ^ Mendy, Angelico; Pinney, Susan M. (June 2022). "Exposure to neonicotinoids and serum testosterone in men, women, and children". Environmental Toxicology. 37 (6): 1521–1528. Bibcode:2022EnTox..37.1521M. doi:10.1002/tox.23503. PMID 35191592.

- ^ Mishani, Hamid Salehi; Jalalizand, Alireza; Modaresi, Mehrdad (January 2022). "The Effect of Increasing the Dose of Acetamiprid and Dichlorvos Pesticides on the Reproductive Performance of Laboratory Mice". Advanced Biomedical Research. 11 (1): 114. doi:10.4103/abr.abr_199_22. PMC 9926034. PMID 36798923.

- ^ Yang, Yeru; Jiao, Xiaoyang; Yao, Fen; Lin, Ze; Guo, Xiaolin; Wang, Meimei; Xie, Qingdong; Liu, Wenhua; Li, Adela Jing; Wang, Zhen (July 2025). "Biomarkers reflecting the toxicity of neonicotinoid insecticides to the central nervous system". Environmental Pollution. 376 126404. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2025.126404. PMID 40355066.

- ^ Li, Adela Jing; Si, Mengya; Yin, Renli; Qiu, Rongliang; Li, Huashou; Yao, Fen; Yu, Yunjiang; Liu, Wenhua; Wang, Zhen; Jiao, Xiaoyang (December 2022). "Detection of Neonicotinoid Insecticides and Their Metabolites in Human Cerebrospinal Fluid". Environmental Health Perspectives. 130 (12). Bibcode:2022EnvHP.130l7702L. doi:10.1289/EHP11374. PMC 9746793.

- ^ Imamura, Tomonori; Yanagawa, Youichi; Nishikawa, Kahoko; Matsumoto, Naoto; Sakamoto, Toshihisa (October 2010). "Two cases of acute poisoning with acetamiprid in humans". Clinical Toxicology. 48 (8): 851–853. doi:10.3109/15563650.2010.517207. PMID 20969506.

- ^ Lee, Christine Li Mei; Brabander, Claire J.; Nomura, Yoko; Kanda, Yasunari; Yoshida, Sachiko (February 2025). "Embryonic exposure to acetamiprid insecticide induces CD68-positive microglia and Purkinje cell arrangement abnormalities in the cerebellum of neonatal rats". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 495 117215. Bibcode:2025ToxAP.49517215L. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2024.117215. PMID 39719252.

- ^ Mishani, Hamid Salehi; Jalalizand, Alireza; Modaresi, Mehrdad (January 2022). "The Effect of Increasing the Dose of Acetamiprid and Dichlorvos Pesticides on the Reproductive Performance of Laboratory Mice". Advanced Biomedical Research. 11 (1): 114. doi:10.4103/abr.abr_199_22. PMC 9926034. PMID 36798923.

- ^ Lee, Christine Li Mei; Brabander, Claire J.; Nomura, Yoko; Kanda, Yasunari; Yoshida, Sachiko (February 2025). "Embryonic exposure to acetamiprid insecticide induces CD68-positive microglia and Purkinje cell arrangement abnormalities in the cerebellum of neonatal rats". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 495 117215. Bibcode:2025ToxAP.49517215L. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2024.117215. PMID 39719252.

- ^ "Acetamiprid".

- ^ "Substance Information - ECHA".

- ^ "Statement on the toxicological properties and maximum residue levels of acetamiprid and its metabolites | EFSA". 15 May 2024.

- ^ Kaur, R.P; Gupta, V; Christopher, A.F; Bansal, P (2015). "Potential pathways of pesticide action on erectile function – A contributory factor in male infertility". Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction. 4 (4): 322–330. doi:10.1016/j.apjr.2015.07.012.

- ^ US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Pesticide Programs, Health Effects Division, Science Information Management Branch: "Chemicals Evaluated for Carcinogenic Potential" (2006)

External links

[edit]- PEA Fact sheet

- Acetamiprid in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)