1993 Four Corners hantavirus outbreak

| 1993 Four Corners hantavirus outbreak | |

|---|---|

The Four Corners Monument, at the spot where the borders of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah meet each other. | |

| Disease | Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome |

| Virus strain | Sin Nombre virus |

| Source | Western deer mouse |

| Location | Four Corners |

| Date | 1993 |

| Confirmed cases | 33 in Four Corners states; 48 nationwide |

| Recovered | 14 in Four Corners states; 21 nationwide |

Deaths | 19 in Four Corners states; 27 nationwide |

| Fatality rate | 58% in Four Corners states; 56% nationwide |

The 1993 Four Corners hantavirus outbreak was an outbreak of hantavirus disease in the United States in the Four Corners region of Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. Hantaviruses that cause disease in humans are native to rodents and, prior to the outbreak, were mainly found in Asia and Europe. Previously, however, they were only known to cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. The outbreak in the Four Corners region led to the discovery of hantaviruses from the Western Hemisphere that could cause disease and revealed the existence of a second disease caused by hantaviruses: hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS). Thirty-three HPS cases were confirmed in the Four Corners states in 1993, with 19 deaths (58%). Nationwide, 48 cases were confirmed, 27 of which (56%) resulted in death.

The earliest confirmed cases of HPS in 1993 occurred in March, but the outbreak was not discovered until May, when a young Navajo couple died within days of each other due to sudden respiratory failure. Investigators quickly found other people with the same symptoms as the couple, and further investigation discovered a new hantavirus as the agent responsible, Sin Nombre virus (SNV), and identified the western deer mouse as its natural reservoir. Public health officials gave advice on how to prevent infection, and the antiviral drug ribavirin was tested on suspected cases. Most cases in 1993, including the first cases to be identified, were in the Four Corners region. As the year went on, an increasing number of cases were identified outside of the area. Before research showed that SNV was not spread between people, there was widespread fear that HPS was contagious. Consequently, Native Americans of the Four Corners region, especially the Navajo, experienced discrimination and racism during the outbreak.

The 1991–1992 El Niño indirectly caused the outbreak by producing a warmer-than-usual 1992–1993 winter and increased rainfall in the spring of 1993 in the Four Corners region. This increased the amount of vegetation available for deer mice for food and shelter, which led to a 10-fold increase in their numbers. The increased population density of deer mice allowed SNV to spread more easily, and with a much larger population, interactions with people were more likely to occur. Further research has uncovered HPS cases before the outbreak as far back as 1959. Since the outbreak, hantaviruses that cause HPS have been identified throughout the Americas. In South America, Andes virus is the main cause of the disease, whereas in North America, SNV remains the most common cause of HPS. Infection is rare but has a case fatality rate of around 40%. Treatment is supportive in nature, and prevention is based around avoiding and minimizing contact with rodents.

Background

[edit]

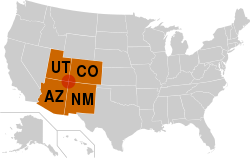

The Four Corners is the name given to where the borders of the US states of Arizona (AZ), Colorado (CO), New Mexico (NM), and Utah (UT) meet each other.[1] The name also refers to the broader area of southwestern CO, northwestern NM, northeastern AZ, and southeastern UT.[2] Most of the area is divided into reservations for Native American nations and tribes, namely the Navajo Nation, the Hopi Reservation, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, the Southern Ute Indian Reservation, the Zuni Indian Reservation, and the Jicarilla Apache Nation.[3] The region is very rural. For example, the Navajo Nation, which occupies a large portion of the region, has a population of approximately 165,000 (2020), with a population density of around 6 people per square mile (2–3 people per square kilometer).[4] Geographically, the area is part of the Colorado Plateau, a desert region with mountains and sedimentary rocky features such as mesas, buttes, and canyons.[1][5][6][7]

Hantaviruses are a family of viruses that constitute the family Hantaviridae. Hantaviruses that cause disease in humans are native to rodents and assigned to the genus Orthohantavirus. Each species of hantavirus is usually transmitted by one rodent species.[8] Prior to the 1993 Four Corners outbreak, Old World hantaviruses were known to cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) and a milder form of it called nephropathia epidemica, mainly in Asia and Europe.[8][9][10] In the Americas, New World hantaviruses that had been identified were not known to infect or cause illness in humans,[11] so the 1993 outbreak would reveal for the first time a disease caused by New World hantaviruses.[9]

Course of outbreak

[edit]The earliest confirmed cases of HPS in 1993 occurred in March.[12][13] In the weeks following the discovery of the outbreak in May, a dozen more cases were reported, mostly among the Navajo.[14] The outbreak continued to worsen in June and peaked in July. The number of new cases then sharply declined in August.[12][13] By August 13, twenty-three cases of hantavirus infection had been confirmed in the Four Corners region. Throughout the Southwest, there were 30 confirmed cases, 20 of which (67%) resulted in death.[15] As the year went on, an increasing number of cases were identified outside of the Four Corners region.[14][16] By October, 60 cases of hantaviral disease had been reported nationwide, about half in the Four Corners region. Around 40 of these cases were confirmed by laboratory, 25 of which led to death.[14][17]

Excluding a spike in October, the number of new cases remained relatively low from August to December.[12][13] Through December 31, forty-eight cases were confirmed nationwide, with 27 deaths (56%).[13] Case fatality rates were similar across age, sex, and race. Most of the infected were male and, in the Four Corners region, all cases either lived in rural areas or visited rural areas prior to falling ill. Of the 33 cases to occur in Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico in 1993, twenty-six occurred during the height of the outbreak from April to July. Of those 33 people, 19 died (58%). No cases were identified in Utah in 1993, the only Four Corners state not to report any cases.[12][13]

Outbreak investigation

[edit]Discovery of outbreak

[edit]

On May 11, 1993, a 19-year-old Navajo man visited the hospital in Crownpoint, NM[18] for fever, muscle pain, chills, headache, and malaise. He was given an antibiotic, a drug for influenza A, and a painkiller and discharged from the hospital. He returned two days later due to persistent symptoms, vomiting, and diarrhea and was discharged with no change in treatment.[19] On the morning of Friday, May 14, he was riding in the back of a car with his family from Crownpoint to Gallup, NM when he became severely short of breath. They stopped their car at a convenience store in Thoreau, NM, about 30 miles (42 km) east of Gallup, and contacted emergency services. By the time help arrived, he had already collapsed due to respiratory failure. An ambulance crew performed CPR on him as he was taken to the Gallup Indian Medical Center, where he was found to have fluid buildup in his lungs (pulmonary edema). Despite efforts to resuscitate him, he died in the hospital's emergency department. The death of the young man, a competitive long-distance runner, due to sudden respiratory failure confused medical staff.[11][14]

Because the man's death was highly unusual, it was required by law to be reported to the New Mexico Office of the Medical Investigator (OMI) in Albuquerque, where autopsies are conducted. The deputy medical investigator in Gallup, Richard Malone, was called in to investigate his death. Malone had investigated a similar death of a 30-year-old Navajo woman a few weeks earlier, in April, at the same medical facility in Gallup. The woman's death, tentatively labeled acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), was examined post mortem by University of New Mexico pathologist Patricia McFeeley, who worked with the New Mexico OMI. The woman's lungs were more than twice as heavy as usual and filled with the clear, yellowish liquid of blood plasma. Test results were negative for known infections that could have caused her death. Malone contacted McFeeley the day of the man's death to discuss the similarities between the two cases, and she agreed to perform an autopsy on the deceased man once permission was obtained from his family.[11][14]

Malone then spoke to the parents of the deceased man and hoped to receive information about what could have caused his death. They told Malone that their son collapsed while they were on their way to the funeral of his 21-year-old fiancée, the mother of his infant child. She had died just five days earlier, on May 9, at the hospital in Crownpoint[20] with the same symptoms as her fiancé. Since Crownpoint is in the Navajo reservation, the medical facility there was not required to report her death to the New Mexico OMI and did not do so.[11][14] Furthermore, due to her history of asthma, her death was not considered alarming at first.[21] After updating McFeeley on the situation, Malone convinced the families of the deceased to have the couple's bodies examined in autopsy. Later that day, McFeeley reported a possible outbreak of an unknown and deadly respiratory illness to the state health department in Santa Fe and prepared for autopsy. The autopsies of the couple showed only severe pulmonary edema with no explanation for the cause of illness.[11][14][22]

Expanded investigation

[edit]

Malone then contacted Bruce Tempest, the medical director of Gallup Indian Medical Center. Tempest recalled having spoken with two physicians who had cared for young, previously healthy tribal members who suddenly died from an unknown respiratory illness. Malone and Tempest agreed that the situation required further action, so they started looking for more cases. Tempest was aware of the three recent cases in New Mexico as well as one from the previous November in Arizona. Health officials in Arizona informed him of another recent case, so on May 17 Malone and Tempest notified the NM Department of Health of their concerns. State officials notified the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on May 18 and began an investigation with the Indian Health Service (IHS) and the Navajo Nation's health department. They examined the homes of the deceased and interviewed their families and the physicians who had cared for them. On May 24, NM state officials sent a letter to clinicians in the Four Corners states that described the illness and situation and asked for any similar cases to be reported to them immediately, which identified several potential cases.[11][14][23]

After learning of the situation, the press reported on May 27[14] that an unexplained illness was killing tribal members in the Four Corners region, which caused great anxiety in the public. Navajo and Hopi people were ostracized from the rest of society, and politicians faced pressure to respond to the situation. On May 28, NM state officials contacted the CDC and asked for assistance. Within hours, a team of investigators was created and Jay Butler, an epidemiologist at the CDC's Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS), was made the leader of the team. Less than a day later, the group arrived at Albuquerque and was transported to the University of New Mexico (UNM). There, they were joined by members of the UNM medical faculty, IHS physicians, infectious disease and toxicology experts, physicians who had treated the deceased, and various state and national health officials.[11][14] Robert Breiman, a respiratory disease expert, would lead the field investigation, while C. J. Peters, the head of the CDC's Special Pathogens Branch, would lead the laboratory work being done in Atlanta, Georgia.[24]

In a meeting that took place from May 29 to May 31,[21] the task force agreed to evaluate any person in the area from January 1, 1993, onward who had radiological imaging that showed evidence of unexplained excess substances in both lungs (bilateral infiltrates) with low levels of oxygen in the blood (hypoxemia) as well as any death accompanied with unexplained pulmonary edema. The group received varying degrees of clinical information about more than 30 suspected cases and considered various causes of illness. Plague, tularemia, and anthrax, among other diseases, were eliminated from consideration due to lack of evidence. The team believed the outbreak to be caused by either a new, aggressive form of influenza, an environmental toxin, or a previously unrecognized pathogen.[11][21]

Hantavirus suspected

[edit]The investigative team began on-site reviews of medical records on June 1 and obtained tissue samples from suspected cases. Meanwhile, epidemiologists interviewed patient and control families and inspected their homes and workplaces. After testing at a local laboratory continually yielded negative results, samples were flown to the CDC in Atlanta for immediate analysis. By Friday, June 4, scientists at the CDC's Special Pathogens Branch had tested IgM antibodies from nine people with 25 different virus samples. Antibodies from every person showed reactivity to three species of hantavirus and none of the other viruses: Hantaan virus, Puumala virus, and Seoul virus. The samples were then shown to be reactive to Prospect Hill virus, a hantavirus that was known to infect voles in Maryland but which had never been associated with human disease or even isolated from human tissue.[11][14]

Several members of the investigative team had experience with and knowledge of HFRS. The disease is characterized by a significant increase in the vascular permeability of endothelial cells, mainly in the kidneys, which causes massive loss of intravascular fluid into the extravascular space in the renal cortex, the renal medulla, and the space behind the lining of the abdominal cavity.[11][28] The loss of intravascular fluid is so severe that the density of blood cells in blood increases due to the loss of liquid, a condition called hemoconcentration. High levels of hemoconcentration were observed in several potential cases in the ongoing outbreak and, combined with the CDC's findings, a hantavirus was suspected of causing the outbreak.[11]

Up to this point in time, hantaviruses identified in the Western Hemisphere were only known to infect rodents, and no instances of human disease caused by them had been described.[11][note 2] There were also no known hemorrhagic fevers native to North America, and none of the infected had traveled abroad or come into contact with foreigners before falling ill.[14] Furthermore, unlike with HFRS, the disease had little kidney involvement; in all cases, the main organs affected were the lungs. Nonetheless, an unknown hantavirus that specifically infected pulmonary capillary endothelial cells was suspected by some members of the investigative team.[11] Acting on the information gathered so far, the CDC dispatched a rodent trapping team to New Mexico, which proceeded to capture around 1,700 rodents from June 7 to mid-August at patient and control sites. The most commonly captured species was the western deer mouse (Peromyscus sonoriensis).[11][14][23]

A new viral disease

[edit]

At the same time as the rodent trapping operation, scientists at the CDC's Special Pathogens Branch worked to identify the new virus. On June 10, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used to obtain a DNA sequence 139 base pairs in length from one segment of the virus's genome from samples taken from two people who had died from the disease.[11][21] Additionally, hantaviral antigens were identified in samples of tissues, such as the endothelium of the pulmonary capillary bed, by the CDC's Viral Pathology Laboratory. On June 16, the same team identified an identical viral base pair sequence and hantavirus antibodies in western deer mice captured on site, which conclusively identified the virus and its natural reservoir.[11] By late June, testing had shown that about 30% of trapped western deer mice[14][23] and smaller percentages of rodents of other species had been infected by the virus.[23][30] Late that summer, researchers confirmed that the virus does not spread between people.[31]

The virus was first cultured in November 1993 by teams at the CDC, which used tissue from a deer mouse trapped near the home of an infected person in New Mexico, and the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick in Frederick, Maryland,[11][23] which used samples taken from a mouse trapped in California and tissue of an infected person in New Mexico.[23] Initially, the CDC proposed to name the virus Muerto Canyon virus after a location in the Navajo reservation,[11] as it is customary to name hantaviruses after where they are discovered.[12][32] The Navajo, however, strongly opposed any further association with the virus because of the racial discrimination against them it had triggered.[11] Moreover, the name was problematic given the location's connection to a past Spanish atrocity,[33] so the Navajo Nation Council voted unanimously to request the CDC to find an alternative name for the virus.[31][33] After successful pushback from the Navajo, the CDC renamed the virus Sin Nombre virus (SNV), Spanish for virus without name.[11][22][33][note 3]

In October 1993, the CDC started referring to the disease as hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS).[37][38][note 4] The Hantavirus Study Group, formed to study the clinical course of the disease, published their findings in the April 7, 1994, edition of The New England Journal of Medicine. They reported 18 people who had either serologic or PCR evidence of infection, most of them young adults. Physical examination of these people showed fever, rapid and shallow breathing (tachypnea), an abnormally fast heart rate (tachycardia), and low blood pressure (hypotension). Severe pulmonary edema occurred in nearly all cases. Laboratory findings included low oxygen levels in the blood (hypoxemia), hemoconcentration, higher than normal white blood cell count in the blood (leukocytosis), abnormally low platelet levels in the blood (thrombocytopenia), and increased time needed for the liver to produce prothrombin and for blood to clot.[11] Early signs of illness included fever, muscle pain, headache, variable respiratory symptoms such as coughing, and gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. The early stage of the disease was then followed by sudden respiratory distress. In all cases reviewed by the CDC, bilateral pulmonary infiltrates developed within two days of hospitalization, and fever, low oxygen levels (hypoxia), and hypotension were present during hospitalization. People who recovered from HPS during the outbreak did not experience any long-term complications.[37]

Government response

[edit]

On June 1, fifty Navajo medicine men met in Window Rock, Arizona to discuss the outbreak and told people to be wary of deer mice and prairie dogs.[21][31][43] Navajo elders knew that mice that entered the home put people at risk of infection when coming into contact with their feces or urine, so they recommended burning contaminated clothing and protecting food from being accessed by rodents.[31] If an infected person died from HPS, then Navajo medicine men would perform blessings and purification ceremonies at locations related to the deceased person's death.[38] The Navajo Nation's government responded to the outbreak by declaring a public health emergency and establishing an Incident Management Team and Inter-Agency Working Group. They also implemented a rodent control program and informed residents about the dangers of HPS and how to trap and control rodents.[39]

Public health officials advised people to prevent rodents from entering their homes, avoid leaving out food that could attract them, and to trap and dispose of rodents while wearing rubber gloves and surgical masks. Poisoning was not recommended since poisoned mice could die somewhere inaccessible and continue to spread the virus. To deal with rodent excretions, health officials recommended soaking them in a chlorine bleach solution and then wrapping them in double plastic bags before disposing of them. People were also warned to avoid inhaling dust in places infested with mice,[44] because the dust could have aerosols that contain the virus.[38]

On June 3, the government opened a toll-free telephone hotline to provide updated information about unexplained respiratory illness and to receive calls about suspected hantavirus cases throughout the country.[45] A day later, the antiviral drug ribavirin was made available for treatment, and intravenous ribavirin stocks were provided to health care facilities in the Four Corners region. Intravenous administration of ribavirin had effectively treated severe infections of Hantaan virus when provided early during illness, so it was tested experimentally on suspected cases during the outbreak.[46] The CDC considered removing the possibility of infection by trapping and poisoning deer mice, but this was rejected as infeasible given the large geographic area and undesirable since mice are an important part of the ecosystem.[31]

Social and economic impact

[edit]During the outbreak, national media were not respectful of the traditional four-day mourning period in Navajo culture. The local community was inundated with reporters and film crews who took pictures of funerals, printed the names of the deceased, and attempted to interview families of the deceased.[14] Sometimes, the media incorrectly reported the names of the deceased and of communities.[38] Media coverage often led to a negative portrayal of Navajo culture and association of the disease with the local area,[31] and various names for the disease entered public discourse, such as Navajo Flu, Navajo Illness, and Four Corners Illness.[33] In many instances, residents posted anti-media signs along roads.[14][38][47] Resentment became so severe that some people refused to assist medical investigators,[14] who also failed to respect mourning practices as they continuously asked for information about recent deaths.[33] Within a month of the outbreak's discovery, there was clear evidence that the disease was not restricted to the Navajo or the Four Corners region. By that point, however, the popular press had moved on to other news and left the Navajo with the stigma that it had created.[14][note 5]

Before the disease's transmission method was confirmed, there was widespread fear that it was contagious. This contributed to discrimination and racism against the Navajo. For example, some restaurants refused to serve Navajo people, while in others staff wore gloves when serving them[14] or threw away their used plates instead of re-using them.[43] The high case fatality rate of the disease only intensified people's fears despite the lack of evidence for human-to-human transmission.[33] Local restaurants saw a significant decline in business, many people stopped going to the movies, and very few people attended the annual Gallup Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial that was held that year. Some people wore surgical masks when leaving the house. In general, though, people in the area only went outside when necessary.[43] In response to news reports, numerous people canceled vacations to the area, and revenue from tourism declined.[31]

Peterson Zah, the president of the Navajo Nation, was a vocal critic of the news coverage of the outbreak and the stigmatization of the Navajo. He said: "The story of Hanta Virus is a perfect example of an intercultural setting and the friction that lies just beneath the surface, and which explodes when unknowing outsiders trample on age-old customs. Deaths and the unknown nature of the illness served only to reinforce stereotypes ... [and] the view of Indians as second-class citizens was further supported."[33] During the outbreak, Zah appealed to the media to respect the privacy of people who lost family members[38] and urged tribal members to assist medical investigators.[48] Before the cause of the outbreak was identified, many Navajo speculated that the disease was brought to the reservation by tourists or that it had escaped from Fort Wingate, located 20 miles (32 km) south of the reservation,[14] because the US Army was in the process of closing its depot there at the time of the outbreak.[43] Later on, some Navajo expressed skepticism toward the connection to mice. One chapter president instead blamed toxic wastes or radioactivity for causing the outbreak.[47][note 6]

Historical analysis

[edit]

A question for the scientific community was why the outbreak occurred. A group of biologists from the University of New Mexico, who were studying the deer mouse population in the Four Corners region during that time period, noticed that the number of deer mice grew 10-fold from May 1992 to May 1993. Working with environmental scientists, the biologists demonstrated that the conditions of the 1991–1992 El Niño caused a relatively warm 1992–1993 winter and a rainy 1993 spring in the Four Corners region. The area had been experiencing drought for a few years, but with more snow melt and rainfall came a relative abundance of springtime vegetation in the region.[11][23][30][50] This provided more shelter and food for local animals, which led to rapid growth of the deer mouse population and, in turn, increased the number of interactions between humans and deer mice.[11] Furthermore, with a higher population density of deer mice, SNV was able to spread more easily among them.[31][51]

According to traditional Navajo beliefs, mice inhabit the nocturnal and outdoor world and humans the daytime and indoor world. The two should not come into contact or sickness and death may occur. When mice enter a house and find a disorderly environment with food laying about, they become angry at the mess and may strike down someone in the household, usually a young, healthy family member.[21][31] Navajo oral tradition spoke of past outbreaks in 1918, 1933, and 1934,[50] which they attributed to excess caused by disharmony. Every year in which an outbreak occurred had excess rain and snowfall, which led to increased rodent food supply and consequently greater rodent populations and more human-rodent interactions.[52]

Genetic analysis of SNV has indicated that it has existed in its natural reservoir since long before the outbreak.[14][22][53][54] Biologists believe that people probably died from hantavirus infection before the outbreak but that their cause of death was unknown at that time.[14] Tempest, when recollecting on people he had treated in the years before the outbreak, said: "I will never be able to know for sure but I believe they were also Hantavirus victims."[43] Serum samples collected in 1991 and 1992 as part of the Navajo Health and Nutrition Survey were tested in June 1993 and showed that three people out of 270 had antibodies to hantaviruses, indicative of past infection.[46] By examining tissue samples from people who died from unexplained ARDS, a 38-year-old man who died in Utah in 1959 became the earliest confirmed case of HPS.[23][30][31]

HPS since the outbreak

[edit]

Following the outbreak, the medical community nationwide was asked to report HPS-like illnesses with unexplained causes. Other hantaviruses responsible for HPS were subsequently found in the US, including Bayou virus, Black Creek Canal virus, and New York virus. The disease has since been found to also occur in Canada, Costa Rica, Panama, and most of South America.[23][53][57] In the Navajo Nation, the government has implemented long-term prevention and control strategies to address HPS, including rodent control programs and public health education,[39] and the CDC Foundation has worked with the Navajo community to implement rodent control measures and educate people about HPS.[58]

SNV remains the most common cause of HPS in North America.[8] It is primarily associated with one rodent species, and other hantaviruses discovered in North America follow the same pattern.[11][53] Most cases occur in rural areas in western states and provinces,[13][53][59] and almost all infections are contracted at home or in the workplace by inhaling aerosols of rodent feces, urine, or saliva.[8][11][53] A few dozen cases occur each year,[8] most from April to August.[13][59] In South America, Andes virus is the most common cause of HPS[53] and is transmitted primarily by the long-tailed pygmy rice rat.[53][60] More than 100 cases occur every year, mostly in Argentina, Brazil, and Chile.[57]

Although HPS was feared by many to be contagious during the 1993 outbreak,[14] human-to-human transmission of hantaviruses has never been verified.[53][61] Because of the health risks imposed by hantaviruses, however, rodents and other small mammals are routinely surveilled to monitor hantavirus circulation.[19][59][62] Environmental factors are associated with HPS incidence. For example, winter severity and cone crop productivity are predictive of the following year's deer mouse population. Harsher winters result in a smaller deer mouse population and by extension fewer HPS cases while warmer winter temperatures in North America entail greater HPS incidence.[50][63][64] Similarly, colder winter temperatures in South America are associated with lower HPS incidence.[64][note 7]

Treatment of HPS is supportive and includes respiratory and cardiac monitoring, mechanical ventilation, hemofiltration, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Despite these measures, the disease still has a high case fatality rate of around 40%.[11][57] Experimental testing of ribavirin during the outbreak did not show a significant benefit to its use,[53] and research has since shown that it is ineffective if administered after the early stage of HPS.[53][63] As a result, the CDC does not recommend ribavirin as a treatment for the disease.[53] No vaccines exist to protect against New World hantavirus infections.[8][53] To prevent infection, the CDC advises people to avoid or minimize contact with rodents, prevent them from entering one's home, keep one's home clear of food that may attract them, and safely clean up after them.[53][66]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Many sources, including those from 1993, identify the natural reservoir of Sin Nombre virus as the species Peromyscus maniculatus. In fact, the natural reservoir of the virus is the species Peromyscus sonoriensis. The reason for this discrepancy is because the two species were previously classified as one, both under the scientific name Peromyscus maniculatus. This species was reorganized in the late 2010s and split into multiple species, including P. maniculatus and P. sonoriensis. The "old" P. maniculatus had a range extending across most of North America, whereas the "new" P. maniculatus is limited to the northeastern parts of the US east of the Mississippi River and southeastern Canada. P. sonoriensis, on the other hand, is found in most of the US west of the Mississippi River, including in the Four Corners region, and in most of southwestern Canada, which corresponds to where Sin Nombre virus infections usually occur.[25][26][27]

- ^ Seoul virus, a pathogenic Old World hantavirus, was detected in the Western Hemisphere before 1993. As such, the 1993 outbreak represents the discovery of pathogenic New World hantaviruses in the Western Hemisphere.[29]

- ^ The first use of the name Muerto Canyon virus was at least in January 1994, as the CDC's January 28, 1994, update about the disease used the name.[12] In the CDC's August 5, 1994, update about the disease, the name Muerto Canyon virus is used again, but the CDC notes that the virus has been proposed to be renamed Sin Nombre virus.[34] By December 2, 1994, the CDC had stopped referring to the virus by its original name, because in the CDC's December 2, 1994, update about the disease, only the name Sin Nombre virus is used.[35] The name Four Corners virus was also used briefly during this time period before being abandoned.[19][36]

- ^ Before hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, the CDC called HPS Navajo flu during their initial response to the outbreak.[39] Throughout 1993, the CDC also referred to it variously as hantavirus-associated respiratory disease,[40] acute hantavirus-associated respiratory disease,[15] hantavirus-associated respiratory illness,[41] and acute hantavirus respiratory illness.[17] In the press, the disease was also called hantavirus-associated ARDS.[42]

- ^ According to Duane Beyal, the executive press officer of the Navajo Nation, local media tended to report on the outbreak better than national outlets. He did, however, praise national media such as Reuters for being quick to respond to criticism.[38]

- ^ In the Navajo Nation, Chapters are the local form of government, and the Chapter President is an elected official.[49]

- ^ In the Northern Hemisphere, winter occurs from December to February. In the Southern Hemisphere, winter occurs from June to August.[65]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Colorado Plateaus Province". National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 22, 2025. Retrieved March 30, 2025.

- ^ Price HL, Clancy NP, Graham TE, Kersten SM, Lavengood KD, Paddock SA, Shoemaker CC, Yeager C, Lehmer EM (March 1, 2014). "Why Is the Four Corners a Hotspot for Hantavirus?". BIOS. 85 (1): 38–47. doi:10.1893/0005-3155-85.1.38.

- ^ Robbins MW (May 18, 1985). "Four Corners". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 30, 2025. Retrieved March 30, 2025.

- ^ Navajo Epidemiology Center (July 2024). "Navajo Nation Population Profile U.S. Census 2020" (PDF). Navajo Nation. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 4, 2024. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- ^ "Geologic Tour of the Colorado Plateau". New Mexico Bureau of Geology & Mineral Resources. Archived from the original on November 9, 2024. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- ^ Klauk E (May 22, 2006). "Physiography of the Navajo Nation". Science Education Resource Center at Carleton College. Archived from the original on June 4, 2024. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- ^ Wheeler R. "The Colorado Plateau Region (Page 2 of 4)". Colorado Plateau Land Use History Network at Northern Arizona University. Archived from the original on February 7, 2006. Retrieved March 30, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Chen R, Gong H, Wang X, Sun M, Ji Y, Tan S, Chen J, Shao J, Liao M (August 8, 2023). "Zoonotic Hantaviridae with Global Public Health Significance". Viruses. 15 (8): 1705. doi:10.3390/v15081705. PMC 10459939. PMID 37632047.

- ^ a b Kuhn JH, Schmaljohn CS (February 28, 2023). "A Brief History of Bunyaviral Family Hantaviridae". Diseases. 11 (1): 38. doi:10.3390/diseases11010038. PMC 10047430. PMID 36975587.

- ^ Avšič-Županc T, Saksida A, Korva M (April 2019). "Hantavirus Infections". Clin Microbiol Infect. 21S: e6 – e16. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12291. PMID 24750436.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Van Hook CJ (November 2018). "Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome—The 25th Anniversary of the Four Corners Outbreak". Emerg Infect Dis. 24 (11): 2056–2060. doi:10.3201/eid2411.180381. PMC 6199996.

- ^ a b c d e f Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (January 28, 1994). "Update: Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome--United States, 1993". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 43 (3): 45–48. PMID 8283965.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Reported Cases of Hantavirus Disease". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. June 26, 2024. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Grady D (May 21, 2019). "Death at the Corners". Discover. Archived from the original on September 12, 2024. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- ^ a b Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (August 13, 1993). "Update: Hantavirus Disease--United States, 1993". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 42 (31): 612–614. PMID 8336693.

- ^ 1993 MMWR reports published on August 5, August 13, September 17, October 29, and so on.

- ^ a b Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (October 8, 1993). "Progress in the Development of Hantavirus Diagnostic Assays -- United States". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 32 (39): 770–771. PMID 8413161.

- ^ Harper & Meyer 1999, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Pottinger, R (Spring 2005). "Hantavirus in Indian Country: The First Decade in Review" (PDF). Am Indian Cult Res J. 29 (2): 35–36.

- ^ Harper & Meyer 1999, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f Sternberg S (June 14, 1994). "Tracking a Mysterious Killer Virus in the Southwest". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2025.

- ^ a b c Johnson 2001.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Tracking a Mystery Disease: The Detailed Story of Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on December 21, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ Harper & Meyer 1999, p. 22.

- ^ Greenbaum IF, Honeycutt RL, Chirhart SE (October 11, 2019). "Taxonomy and Phylogenetics of the Peromyscus Maniculatus Species Group". Special Publications of the Museum of Texas Tech University. 71: 559–575. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7221125.

- ^ Whitmer SL, Whitesell A, Mobley M, Talundzic E, Shedroff E, Cossaboom CM, Messenger S, Deldari M, Bhatnagar J, Estetter L, Zufan S, Cannon D, Chiang CF, Gibbons A, Krapiunaya I, Morales-Betoulle M, Choi M, Knust B, Amman B, Montgomery JM, Shoemaker T, Klena JD (July 11, 2024). "Human Orthohantavirus Disease Prevalence and Genotype Distribution in the U.S., 2008–2020: A Retrospective Observational Study". Lancet Reg Health Am. 37: 100836. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2024.100836. PMC 11296052. PMID 39100240.

- ^ Finkbeiner A, Khatib A, Upham N, Sterner B (December 21, 2024). "A Systematic Review of the Distribution and Prevalence of Viruses Detected in the Peromyscus maniculatus Species Complex (Rodentia: Cricetidae)". bioRxiv 10.1101/2024.07.04.602117.

- ^ Koehler FC, Di Cristanziano V, Späth MR, Hoyer-Allo KJ, Wanken M, Müller RU, Burst V (January 29, 2022). "The Kidney in Hantavirus Infection-Epidemiology, Virology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis and Management". Clin Kidney J. 15 (7): 1231–1252. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfac008. PMC 9217627. PMID 35756741.

- ^ Clement J, LeDuc JW, Lloyd G, Reynes JM, McElhinney L, Van Ranst M, Lee HW (July 17, 2019). "Wild Rats, Laboratory Rats, Pet Rats: Global Seoul Hantavirus Disease Revisited". Viruses. 11 (7): 652. doi:10.3390/v11070652. PMC 6669632. PMID 31319534.

- ^ a b c Borowski S (January 13, 2013). "The Virus That Rocked the Four Corners Reemerges". American Association for the Advancement of Science. Archived from the original on March 25, 2025. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Stumpff LM (2010). "Hantavirus and the Navajo Nation: A Double Jeopardy Disease" (PDF). The Evergreen State College. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 25, 2025. Retrieved March 7, 2025.

- ^ Mariappan V, Pratheesh P, Shanmugam L, Rao SR, Pillai AB (July 16, 2021). "Viral Hemorrhagic Fever: Molecular Pathogenesis and Current Trends of Disease Management-An Update". Curr Res Virol Sci. 2: 100009. doi:10.1016/j.crviro.2021.100009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Radcliffe C (June 30, 2021). "The Tragedy of Names". Yale J Biol Med. 94 (2): 375–378. PMC 8223546. PMID 34211356.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (August 5, 1994). "Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome -- Northeastern United States, 1994". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 43 (30): 548–549, 555–556. PMID 8035772.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (December 2, 1994). "Emerging Infectious Diseases Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome -- Virginia, 1993". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 43 (47): 876–877. PMID 7969008.

- ^ Hjelle B, Lee SW, Song W, Torrez-Martinez N, Song JW, Yanagihara R, Gavrilovskaya I, Mackow ER (December 1995). "Molecular Linkage of Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome to the White-Footed Mouse, Peromyscus Leucopus: Genetic Characterization of the M Genome of New York Virus". J Virol. 69 (12): 8137–8141. doi:10.1128/JVI.69.12.8137-8141.1995. PMC 189769. PMID 7494337.

- ^ a b Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (October 29, 1993). "Update: Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome--United States, 1993". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 42 (42): 816–820. PMID 8413161.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bales F (June 1, 1994). "Hantavirus and the Media: Double Jeopardy for Native Americans". Am Indian Cult Res J. 18 (3): 251–263. ISSN 0161-6463.

- ^ a b c Burrell D (November 7, 2023). "Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS), Native Communities and Public Health Epidemic Surveillance in the United States". Arab Gulf J Sci Res. 42 (4): 1271–1286. doi:10.1108/agjsr-04-2023-0165.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (July 30, 1993). "Hantavirus Disease -- Southwestern United States, 1993". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 42 (29): 570–572. PMID 8332114.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (September 17, 1993). "Update: Hantavirus-Associated Illness -- North Dakota, 1993". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 42 (36): 707. PMID 8361465.

- ^ Harper & Meyer 1999, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e Donovan B (May 17–18, 2008). "Year of Fear: Medicine Men Knew Cause of Hantavirus". The Gallup Independent. Archived from the original on March 17, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2025.

- ^ Harper & Meyer 1999, p. 37.

- ^ Tappero JW, Khan AS, Pinner RW, Wenger JD, Graber JM, Armstrong LR, Holman RC, Ksiazek TG, Khabbaz RF (February 7, 1996). "Utility of Emergency, Telephone-Based National Surveillance for Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome. Hantavirus Task Force". JAMA. 275 (5): 398–400. PMID 8569020.

- ^ a b Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (June 18, 1993). "Update: Outbreak of Hantavirus Infection--Southwestern United States, 1993". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 42 (23): 441–443. PMID 8502218.

- ^ a b Pressley, SA (June 18, 1993). "Navajos Protest Response to Mystery Flu Outbreak". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 7, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- ^ Harper & Meyer 1999, p. 43.

- ^ "Local Governance Act of 1998". Navajo Nation. Archived from the original on February 24, 2025. Retrieved April 7, 2025.

- ^ a b c Fimrite P (September 23, 2012). "Hantavirus Outbreak Puzzles Experts". SFGate. Archived from the original on July 7, 2022. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- ^ Harper & Meyer 1999, p. 72.

- ^ MacDonald J (March 14, 2018). "Solving a Medical Mystery with Oral Traditions". JSTOR Daily. Archived from the original on June 23, 2024. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Jacob AT, Ziegler BM, Farha SM, Vivian LR, Zilinski CA, Armstrong AR, Burdette AJ, Beachboard DC, Stobart CC (November 9, 2023). "Sin Nombre Virus and the Emergence of Other Hantaviruses: A Review of the Biology, Ecology, and Disease of a Zoonotic Pathogen". Biology (Basel). 12 (11): 1143. doi:10.3390/biology12111413. PMC 10669331. PMID 37998012.

- ^ Klempa B (October 2018). "Reassortment Events in the Evolution of Hantaviruses". Virus Genes. 54 (5): 638–646. doi:10.1007/s11262-018-1590-z. PMC 6153690. PMID 30047031.

- ^ "Outbreak of Hantavirus Infection in Yosemite National Park". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 1, 2012. Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2025.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (November 23, 2012). "Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome in Visitors to a National Park--Yosemite Valley, California, 2012". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 61 (46): 952. PMID 23169317.

- ^ a b c Afzal S, Ali L, Batool A, Afzal M, Kanwal N, Hassan M, Safdar M, Ahmad A, Yang J (October 12, 2023). "Hantavirus: An Overview and Advancements in Therapeutic Approaches for Infection". Front Microbiol. 14: 1233433. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1233433. PMC 10601933. PMID 37901807.

- ^ "A Unique Partnership Tackles Hantavirus in the Navajo Nation". CDC Foundation. June 3, 2020. Archived from the original on December 7, 2024. Retrieved April 18, 2025.

- ^ a b c Warner BM, Dowhanik S, Audet J, Grolla A, Dick D, Strong JE, Kobasa D, Lindsay LR, Kobinger G, Feldmann H, Artsob H, Drebot MA, Safronetz D (December 2020). "Hantavirus Cardiopulmonary Syndrome in Canada". Emerg Infect Dis. 26 (12): 3020–3024. doi:10.3201/eid2612.202808. PMC 7706972. PMID 33219792.

- ^ Medina RA, Torres-Perez F, Galeno H, Navarrete M, Vial PA, Palma RE, Ferres M, Cook JA, Hjelle B (March 2009). "Ecology, Genetic Diversity, and Phylogeographic Structure of Andes Virus in Humans and Rodents in Chile". J Virol. 83 (6): 2446–2459. doi:10.1128/JVI.01057-08. PMC 2648280. PMID 19116256.

- ^ Toledo J, Haby MM, Reveiz L, Sosa Leon L, Angerami R, Aldighieri S (October 17, 2022). "Evidence for Human-to-Human Transmission of Hantavirus: A Systematic Review". J Infect Dis. 226 (8): 1362–1371. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiab461. PMC 9574657. PMID 34515290.

- ^ Kim WK, Cho S, Lee SH, No JS, Lee GY, Park K, Lee D, Jeong ST, Song JW (January 8, 2021). "Genomic Epidemiology and Active Surveillance to Investigate Outbreaks of Hantaviruses". Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 10: 532388. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2020.532388. PMC 7819890. PMID 33489927.

- ^ a b D'Souza MH, Patel TR (August 7, 2020). "Biodefense Implications of New-World Hantaviruses". Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 8: 925. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00925. PMC 7426369. PMID 32850756.

- ^ a b Tian H, Stenseth NC (February 21, 2021). "The Ecological Dynamics of Hantavirus Diseases: From Environmental Variability to Disease Prevention Largely Based on Data From China". PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 13 (2): e0006901. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006901. PMC 6383869. PMID 30789905.

- ^ Salisbury RD, Barrows HH, Tower WS (1912). The Elements of Geography. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 64. Retrieved April 2, 2025.

- ^ "Hantavirus Prevention". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 13, 2024. Archived from the original on March 1, 2025. Retrieved March 16, 2025.

Books cited

[edit]- Harper DR, Meyer AS (1999). Of Mice, Men, and Microbes. Academic Press. ISBN 9780080491981.

- Johnson KM (2001). "Hantaviruses: History and Overview". In Schmaljohn C, Nichol ST (eds.). Hantaviruses. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9783540410454.

Further reading

[edit]- Duchin JS, Koster FT, Peters CJ, Simpson GL, Tempest B, Zaki SR, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Nichol S, Umland ET, et al. (April 7, 1994). "Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome: A Clinical Description of 17 Patients with a Newly Recognized Disease. The Hantavirus Study Group". N Engl J Med. 330 (14): 949–955. doi:10.1056/NEJM199404073301401. PMID 8121458.