War aims of the First World War

The war aims of the First World War were formulated after the conflict began, reflecting the territorial, political, and economic objectives pursued by the belligerent states. Governments and public opinion often did not distinguish between war aims, causes of war, and the origins of the conflict. While some war aims, whether publicly declared or kept confidential, included extensive demands such as territorial annexations, these objectives alone do not fully explain the decision to enter the war. In certain cases, however, war aims and the casus belli overlapped, as seen with countries such as Italy, Romania, and Bulgaria.

During the First World War, additional war aims developed for the conflict, extending beyond the original casus belli. According to Professor Ernst Rudolf Huber, from the perspective of annexationist objectives, neither side can be accused of having entered the war to conduct a war of conquest.[1] During and after the conflict, war aims and the question of responsibility were often seen as closely connected, although this association was largely superficial.[2] War aims were also employed as instruments of warfare, particularly by the Western Allies.[3]

Difficulties in formulation

[edit]

The formulation of war aims was a sensitive issue for most belligerents during the First World War. Many governments viewed the declaration of specific objectives as potentially risky, fearing that unfulfilled aims could later be interpreted as a failure or defeat. In the early stages of the war, references to war aims were typically vague, with governments focusing instead on rallying public support around the general goal of victory.[4] Until 1917, detailed war aims remained secondary to promoting the perceived heroic nature of the conflict. However, publicly stated expansionist ambitions often negatively influenced the stance of neutral countries. Over time, the public articulation of war aims became increasingly necessary to assess the relevance and feasibility of specific objectives.[5]

Buffer zones and border adjustments remained central to strategic considerations during the First World War, despite technological advancements that had reduced the importance of geographical distance compared to the 19th century. Historian Gerhard Ritter noted that the limited military significance of territorial changes in the context of mass warfare, modern transportation, and air power was not widely understood, even among professional soldiers,[6] and was therefore also overlooked by politicians and the press. Nationalism heightened public sensitivity to border issues and territorial losses, often resulting in significant and lasting diplomatic tensions. In the context of nationalism and imperialism, few recognized that territorial annexations were unlikely to weaken adversaries or secure lasting peace, and instead risked further conflict.[7]

Like the Allied powers, the Central Powers employed their war aims to mobilize domestic support, influence allies, appeal to neutral states, and deter adversaries.[8] War aims on both sides also had an economic dimension, involving efforts to occupy or control key commercial sectors to promote exports and secure access to raw materials.

War aims of the central powers

[edit]German empire

[edit]War aims at the outbreak of the conflict

[edit]

At the outset of the First World War, the German Empire considered the conflict a defensive war. However, early military successes on the Western Front led to the development of expansive annexationist ambitions.[9] The initial economic objective—focused on colonial expansion in Africa and Asia Minor—was soon supplanted by a broader goal of asserting German dominance within Europe, motivated by concerns over Germany’s central geographic position. Through extensive territorial annexations in eastern and western Europe, the Empire aimed to establish long-term continental hegemony, which was seen as a prerequisite for achieving global influence.[10][11]

On 9 September 1914, Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, in collaboration with Kurt Riezler, outlined Germany’s war aims in the Septemberprogramm. Since the Empire’s foundation, German policy had been oriented toward consolidating power and pursuing global ambitions. The Septemberprogramm emphasized securing Germany’s position through the weakening of France, which was to be stripped of its great power status and rendered economically dependent on Germany. Proposed concessions included the cession of the Briey iron basin and the French coastline between Dunkirk and Boulogne-sur-Mer.[12] Concerning Belgium, the plan called for the annexation of Liège and Verviers into Prussia and the transformation of Belgium into a vassal state and economic dependency.[12] The program also included the proposed annexation of Luxembourg and the Netherlands.[13]

The Septemberprogramm also aimed to reduce Russian influence in Eastern Europe and to consolidate German power through the establishment of a customs union.[14] This proposed economic bloc would have included France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Austria-Hungary, Poland, and potentially Italy, Sweden, and Norway. The program reflected the strategic objectives of Germany’s political, economic, and military leadership. Industrialists, particularly those in the steel industry, supported measures to limit the autonomy of other states, notably concerning control over the Briey-Longwy basin.[15] The Septemberprogramm represented the synthesis of various plans regarding the future political and economic order in Europe.

Most members of the Reichstag supported the annexationist goals outlined in the program, with the Social Democratic Party being the primary opposition.[16] By 1915, internal contradictions in war aims began to emerge.[17] Initially developed in the optimistic atmosphere of the war’s early stages, these aims were increasingly seen as unrealistic. In late 1914, Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg prohibited public discussion of war aims to avoid alienating neutral countries and to manage domestic concerns, particularly among the working class. This restriction, however, was short-lived. Under pressure from the Third Supreme Army Command (Oberste Heeresleitung, OHL) and in response to the need for continued psychological mobilization of the population, the ban was lifted. The resumption of public debate on war aims became a tool for promoting total war and ideologically motivated military conduct.[18]

A central element of Germany's war aims in the West during the First World War was the status of Belgium. Since the formulation of the Septemberprogramm, the prevailing objective among German political leaders had been to transform Belgium into a vassal state, accompanied by territorial annexations wherever feasible.[19] In the East, a primary objective was the establishment of control over Poland, including the annexation of a border strip.[20] Additional territorial ambitions focused on regions such as Courland and Lithuania, motivated both by geographic proximity and the presence of non-Russian populations, including a minority of Baltic Germans.[21][22] Plans for these eastern territories included the displacement of local populations, such as Latvians, and the resettlement of ethnic Germans—particularly those previously living in the Russian Empire—on lands owned by the crown, the church, or large estates. These settlements were often intended to complement the holdings of the Baltic German nobility. Ethno-nationalist (völkisch) ideas played a significant role in shaping Germany's colonization policies, integrating demographic and ideological considerations into its broader war aims.[23]

The objective of establishing a German Central Africa was a significant component of Germany's colonial war aims during the First World War. In August and September 1914, Wilhelm Solf, Secretary of State for the Colonies, proposed the partition of French, Belgian, and Portuguese colonial territories in Africa, a plan later incorporated into the Septemberprogramm by Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg.[24] Although annexationist sentiment peaked in mid-1915, public support for such ambitions declined as the war's human and material costs became increasingly evident. Initial enthusiasm gave way to widespread disillusionment.[25] Annexationist propaganda had the greatest influence among industrial and intellectual elites, while broader segments of the population remained less receptive—a trend that would shift during the Second World War. In the latter half of the conflict, the socialist demand for a "peace without annexations"[26] gained significant popular support. Public morale, particularly among soldiers, increasingly opposed the Pan-German League and its more aggressive nationalist elements.

War aims toward the end of the war

[edit]

As part of Germany’s Randstaatenpolitik (policy toward border states), which aimed to push back Russia by creating a buffer zone of states from Finland to Ukraine, the focal point of German expansionist ambitions in the East lay primarily in the Baltic countries. The majority of Germany’s leadership, from the right to the anti-tsarist left, adhered to a concept of division.[27] The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed with the Soviet Union on 3 March 1918, stipulated the secession of Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, and Courland from Russia, as well as the independence of Ukraine and Finland. Russia was required to withdraw its troops from Finland and the province of Kars, including the cities of Ardahan, Kars, and Batumi. As a result, Russia lost 26% of the territories under its control, 27% of its arable land, 26% of its railway network, 33% of its textile industry, 73% of its steel industry, and 75% of its coal mines.[28]

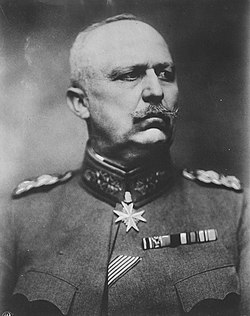

In 1918, Germany reached the height of its war aims. Between the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and the defeat of the Central Powers, the German Empire developed plans for extensive annexations in Eastern and Southeastern Europe. During negotiations for additional clauses to the treaty, General Erich Ludendorff aimed to extend German influence over Lithuania, Estonia, Crimea, the Cossack territories of the Kuban and Don as a link to the Caucasus, as well as the Caucasus region, the Tatar territories, the Astrakhan Cossacks, the Turkmens, and Turkestan. Although initially reluctant, the German Emperor eventually accepted these proposals.[29] The plan also envisaged dividing Russia into four independent tsarist states following the cession of Poland, the Baltic provinces, and the Caucasus. These included Ukraine, the Südostbund (Ciscaucasia) as an anti-Bolshevik zone between Ukraine and the Caspian Sea, Central Russia (Zentralrussland), and Siberia. One objective of this strategy was to establish a geopolitical corridor toward Central Asia, to challenge British interests in India.[30] The Südostbund project, however, conflicted with the territorial ambitions of the Ottoman Empire.[31]

General Erich Ludendorff did not consider a permanent separation of Ukraine from Russia to be viable. As a result, he pursued a strategy aimed at expanding the German sphere of influence within Russian territory to counter the spread of Bolshevism. The short-lived State of Crimea-Taurida was envisioned as a settlement area for ethnic Germans from Russia, while the Kuban and Don regions were intended to serve as a strategic link to the Caucasus. Crimea was to function as a colonial territory under permanent German occupation and as a maritime base for projecting influence into the Caucasus and the Near East. Ludendorff also proposed the creation of a German-aligned Caucasian bloc centered on Georgia, although this proved impractical due to geographic distance and the prevailing influence of the Ottoman Empire.[32][33] The supplementary treaties to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed on 27 August 1918, imposed further territorial concessions on Russia but also marked a temporary halt to Germany’s annexation efforts.[11] While the border states from Finland to Georgia were not formally annexed, they remained economically and militarily dependent on the German Empire.

The weakening of Russian power following the revolution, combined with the underestimation of the significance of the United States entering the war, contributed to an increased push within German leadership circles for expansion toward the East.[34] At the same time, discussions emerged regarding whether a Central Europe dominated by Germany could remain viable in a future conflict against the two major maritime powers, the United Kingdom and the United States, which had access to extensive global economic resources. In response, German strategic planners proposed the creation of a German-controlled sphere stretching from the Bay of Biscay to the Ural Mountains. This eastern sphere was envisioned as economically self-sufficient, militarily secure, and resistant to blockades. It was intended to serve as a counterbalance to the maritime powers and gradually replaced the earlier concept of a German-led Central Europe in war planning.[35] The idea of a weak Central Europe, characterized by the dependency of smaller sovereign states and limited access to raw materials, was subsequently abandoned.[36]

German war aims and research

[edit]Unlike many other belligerent powers, Germany entered the First World War without a defined or widely accepted war aim. This absence of a natural objective led to the formulation of artificial goals that lacked resonance with the general population.[37] The resulting focus on territorial and political expansion reflected a broader conception of state power characteristic of the Wilhelmine era, which emphasized power accumulation as central to national existence. Within this framework, power struggles were viewed as the primary force shaping history,[38] and acts such as initiating war or seizing foreign territory were considered inherent rights of sovereign states. Germany’s approach to war aims, marked by their explicit formulation and the use of all available political and military instruments to achieve them, limited the possibility of a broader political transformation or a shift in public opinion during the conflict.[39]

The debate over Germany’s war aims was not a conflict between expansion and peace, but between moderate and extreme interpretations of a "German peace." Annexationists sought to address the Empire’s foreign policy challenges through territorial expansion, while moderates pursued internal reforms, without entirely rejecting the possibility of expansion. Although less influential, the moderates found some support in Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg. Unlike other opposition groups, they did not engage in mass mobilization and remained disconnected from the working class. As a result, they lacked influence compared to the widespread annexationist movement, revealing an imbalance between strong institutional authority and limited grassroots support. Within the annexationist camp, particularly before the formation of the third OHL, the reverse dynamic existed. This contrast contributed to a sense of inferiority among moderates, despite later developments aligning more closely with their position. This perspective persisted into the Weimar Republic.[40]

The motives behind the war aims movement in Germany were diverse and interconnected, encompassing fears, economic interests, and ambitions of power. Nationalist agitation influenced public opinion and constrained the actions of the imperial government under Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg, contributing to a growing disparity between global political aspirations and continental realities.[41] German foreign policy, both before and during the war, reflected enduring political and geographical divisions within the country. The naval party, heavy industry, the anti-plutocratic segment of the Prussian middle class, and the Junker class in northern Germany supported a break with the United Kingdom. In contrast, the conflict with Russia received more backing in southern Germany, particularly among Habsburg sympathizers and financial circles. Bethmann Hollweg was aligned with proponents of a continental policy, and, during the early years of the war, his primary political opponent was Alfred von Tirpitz.[42]

The pursuit of territorial expansion was viewed as a means to address internal issues within the German Empire. Agrarian and industrial elites sought to avoid domestic reforms by securing a military victory, thereby maintaining their social status. A conciliatory peace was considered unacceptable by the German leadership, as it was perceived to threaten their power as much as a military defeat. The concept of an Imperium Germanicum failed due to both persistent strategic errors[43] and structural weaknesses within the Empire, which lacked the capacity for restraint in its continental ambitions. This failure was also influenced by contemporary demands and the principle of national self-determination, which the Empire did not fully accept.[42] According to Hans-Ulrich Wehler’s theory of social imperialism, the Empire, beginning under Otto von Bismarck, used foreign policy—particularly colonial expansion—as a strategy to offset internal social tensions. The war provided an opportunity to advance this approach. In this context, war aims served a unifying function for the ruling elites, acting as a mechanism for political and social cohesion within a divided Wilhelmine society.[44][45]

Due to its military strength, economic capacity, and territorial size, the German Empire was considered the most powerful among the European states. Its expansionist ambitions came into conflict with the established European balance of power. According to Ludwig Dehio, if Germany had managed to prevail against a coalition of the major powers, it would have secured a hegemonic position in Europe and globally.[46] During the war, Germany demonstrated its status as a world power by sustaining conflict against Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The desire to be recognized as a world power was closely linked to the aim of possessing a large colonial empire, which was seen as a symbol of such status. German imperialists considered the country's colonial holdings insufficient compared to other world powers, including France. Although Germany was strong enough to attempt to position itself as a third global power alongside Russia and the Anglo-American bloc, it lacked the means to achieve this objective.[47] Among the obstacles was the impracticality of establishing an empire extending from Flanders to Lake Peipus, and from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea and the Aegean, with colonies and military bases, including a Central African territory envisioned as an extension of Central Europe. Such an accumulation of power would likely have provoked resistance movements, similar to the wars of liberation that occurred during the Second World War in response to German expansion.[48]

Pre-war politics, the war aims formulated before 1914, and those of 1918 formed a coherent continuum, as did the objectives pursued by various political groups, parties, and social classes.[49] The German Empire’s war aims policy was shaped by an overestimation of national power and a lack of realism. It was marked by the combination of economic reasoning with emotional motivations, an inflated perception of Germany’s strength, and an underestimation of adversaries.[50][51] The alliance between the landed aristocracy and industrial interests reflected the structural tension within a conservative system in an industrializing agrarian state, where the conservatives’ economic influence was in decline.[52]

For an extended period, the dominant view in Western Germany held that there was no link between Germany’s war aims in the First World War and those of the Second. However, among the belligerent powers, only German nationalists—particularly Pan-Germanists—implemented the displacement of population groups considered hostile. The modification of ethnic composition to strengthen imperial authority was pursued in line with Prussian policies in the Ostmark, through the acquisition of crown estates and church lands and the expulsion of certain population segments. Nationalist plans for evacuation and colonization in the eastern territories (Ostraum) existed from the beginning of the war, though they only gained significant support among the Empire’s leadership in 1918, following the temporary success of the German Supreme Army Command.[53] The proposed colonization of Polish border areas by ethnic Germans from Russia (Russlanddeutsche), as envisioned by the Supreme Army Command, corresponded to the later projects of the National Socialists. National Socialism adopted the concept of eastern expansion with greater intensity and violence than the German Empire had pursued. While imperial advocates of borderland projects primarily supported systematic land acquisition, in the tradition of Prussian policy, they did not propose violent evacuations or human rights violations, even during wartime, as occurred under the Third Reich.[54]

Ludendorff’s nationalist (völkisch) policy, particularly in the East in 1918, anticipated several elements of Hitler’s later racial policies. Efforts in the summer of 1918 to establish a greater German presence in the East included colonization and evacuation plans that bore resemblance to aspects of Hitler’s Ostpolitik, though without the concepts of treating Slavs as helots or carrying out mass murder of Jews, which were not present during the First World War. Many annexationists continued to adhere to outdated agrarian models, viewing territorial expansion and rural colonization as solutions to domestic pressures caused by rapid industrialization and population growth. Hitler’s long-term goal of creating an eastern empire, already formulated in the 1920s, found precedents in the policies and practices of 1918. The rhetoric of “betrayal” that developed in 1918 contributed to the ideological conditions later adopted by National Socialism. Although Hitler’s program maintained continuity with the broader war aims of the First World War, it diverged fundamentally through its incorporation of racial ideology.[55][56] In both conflicts, military entry into the West was comparatively restrained, while operations in the East were marked by greater brutality, which intensified under Hitler.[57]

Austria-Hungary

[edit]Austria-Hungary entered the First World War to defend its interests in the Balkan Peninsula and to safeguard its continued existence, which it perceived as being threatened by Russia. At the onset of the conflict, internal differences among the empire’s various ethnic groups receded in importance. Austria-Hungary aimed to annex parts of Serbia, as well as territories from Montenegro, Romania, Albania, and Russian Poland. In response to the era’s rising nationalism, the empire maintained its commitment to the concept of a universal, multinational state. During the initial phase of the war—before military defeats in Galicia and Serbia—the Austro-Hungarian leadership expressed specific territorial ambitions. However, these acquisition plans were soon overshadowed by the more immediate concern of preserving the empire’s survival.[58]

Common council of ministers of January 7, 1916

[edit]

Following the conquest of Serbia in late 1915, Austria-Hungary faced the question of how to address the South Slavs and the extent to which Serbia should be incorporated into the empire. The Common Council of Ministers convened on January 7, 1916, with the expectation of an imminent decisive military development. The purpose of the meeting was to define the monarchy's war aims. Participants included the Austrian Prime Minister Karl Stürgkh, the Hungarian Prime Minister István Tisza, the joint ministers Ernest von Koerber (Finance), Alexander von Krobatin (War), and Stephan Burián (Foreign Affairs and president of the conference), along with Chief of the General Staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf.[59]

According to Burián, the conference aimed to address the current military and political situation and to determine the objectives to be pursued through the war. The primary goals were the integrity and security of the monarchy, as well as the intention to benefit from recent military victories. The participants discussed the political consequences of the conquests for the future of the empire.[60] Burián proposed that Serbia, after allocating certain territories to Bulgaria, should be further reduced through the cession of former Albanian lands and a broader border adjustment, including the provision of two bridgeheads to the monarchy.[61] The remaining territory would be a small, mountainous country with approximately 1.5 million inhabitants. While its incorporation would present legal, political, and economic challenges, Burián considered it feasible given the monarchy’s historical adaptability.

Like Conrad, Stephan Burián advocated for the elimination of Serbia as a center of national agitation and as an instrument of enemy powers.[62] The leadership recognized that even if Serbia were deprived of political autonomy, it would likely remain a source of opposition to the Dual Monarchy. While Burián presented himself as pursuing a moderate position, his diary entry from the same day indicated his support for the complete annexation of Serbia.[63] He also acknowledged that such an incorporation would entail burdens, including potential unrest. He identified the key issue as determining whether it would be more manageable if only 66% of Serbs were subjects of the monarchy while 34% remained in an independent state, or if all Serbs were integrated. He concluded that the appropriate course had yet to be decided.[64]

The question of Serbia's future was closely linked to the prospect of peace. Burián was unwilling to endanger a potential peace agreement if it required the restoration of Serbia as a condition acceptable to Russia.[65]

Burián did not consider a reduced Montenegro to pose a threat comparable to Serbia but insisted on its unconditional submission and the cession of Mount Lovćen, its coastline extending to Albania, and its Albanian territories. Concerning Albania, Burián supported the establishment of an independent state, which he believed would be viable despite internal difficulties, following the restitution of territories previously granted to Serbia and Montenegro after the Balkan Wars.[66] This independent Albania would exist under Austro-Hungarian protection. Burián described this policy as "conservative and purely defensive,"[67] intended to secure the monarchy's dominance in the Balkans.[68]

Following territorial gains in the north, the possibility of ceding certain areas to Greece in the south was considered as a means to ensure Greek neutrality. In the event of a partition of Albania, as proposed by Conrad, the annexation of the northern region was viewed as a significant burden. The Foreign Minister publicly opposed the inclusion of Bulgaria in the division of Albanian territory near the Adriatic, as suggested by Conrad.[69] Given Bulgaria's existing difficulties in assimilating its Serbian acquisitions, granting it additional territory in Albania was seen as undermining the monarchy’s interests in an independent Albania. The preferred course of action was to establish Albanian autonomy under Austro-Hungarian protection. If this proved unfeasible, a partition limited to Greece was considered the alternative.[70]

Bulgaria

[edit]

Bulgaria sought to realize the concept of Greater Bulgaria as defined by the Treaty of San Stefano in 1878 and aimed to recover territories lost during the Second Balkan War to Greece and Serbia. Bulgarian claims over Macedonia were supported by the influence of Macedonian Bulgarian refugees who held prominent positions in politics and the military. The Macedonian question was regarded as a national priority by the political leadership, the Orthodox Church, and the army.[71] The government under King Ferdinand also envisioned a personal union with the Principality of Albania, expanded by adjacent Serbian regions, and sought to reclaim the provinces of Dráma, Serrès, and Kavála from Greece, Dobruja from Romania, and territories east of the Morava River from Serbia.[72]

In early 1915, French Foreign Minister Théophile Delcassé offered Serbia’s Macedonian territory to Bulgaria in exchange for neutrality or alignment with the Entente, first through Nikola Guenadiev and later via Prince Jean of Orléans. The British, seeking support amid difficulties in the Dardanelles campaign, also approached Bulgaria. In March 1915, Minister Edward Grey suggested that Bulgaria could obtain the port of Kavála if it declared war on the Ottoman Empire.[73] On May 29, 1915, following Italy’s entry into the war, the Entente powers—France, Britain, Russia, and Italy—offered Bulgaria Eastern Thrace up to Enez and Serbian Macedonia as far as Monastir in exchange for joining the war against the Ottomans.[74] Serbia, however, categorically rejected the proposal.[75] Bulgaria subsequently aligned with the Central Powers, signing a secret alliance with Germany on September 6, 1915, and entered the war against Serbia in October 1915, during a joint offensive by German and Austro-Hungarian forces. This led to the evacuation of the Serbian army through the Adriatic and the occupation of Serbia by Bulgarian and Austro-Hungarian troops.[65]

In February 1918, Bulgaria proposed assisting the Ottoman Empire in the conquest of the Russian Caucasus in exchange for Adrianople and the left bank of the Maritsa River. The proposal was unsuccessful.[76]

War aims of the Allies

[edit]British Empire

[edit]Guarantee the neutrality and territorial integrity of the states near the English Channel, namely Belgium and the Netherlands, which are considered a buffer zone protecting British territory from invasion.[77]

Continue a consistent policy since the end of the Hundred Years’ War: maintaining the continental balance of power in Europe (ensuring Germany does not become too powerful). Limit German naval power, which threatens British commerce and its supremacy over the world’s seas and oceans.[78]

Russia

[edit]Since the Bosnian crisis of 1908, Tsar Nicholas II and part of Russian public opinion expressed concern over the rise of Pan-Germanism, represented by the alliance between Germany and Austria-Hungary. The Pan-Slavic movement, led by Prince Grigori Trubetskoy, head of Ottoman and Balkan affairs at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, advocated for support to Serbia and the extension of Russian influence in the Balkans and Constantinople. Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich, the Tsar’s uncle, also supported this position.[79]

At the outset of the war, Nicholas Nikolaevich was appointed commander of the Russian Imperial Army. With the approval of the Tsar and the Council of Ministers, he proclaimed the Poles and other Slavic populations of Austria-Hungary, inviting them to support the Russian cause. However, this appeal was soon undermined by a policy of Russification implemented by the Russian army’s administration, schools, and clergy in Eastern Galicia and Bukovina, following their occupation after the Galician offensive in 1914.[80]

Foreign Minister Sergey Sazonov openly expressed Russia’s objectives concerning Constantinople and the Straits. On March 4, 1915, he informed the Entente ambassadors that, in the event of victory, Russia intended to occupy the Straits, the Asian shore up to the Sakarya River, the European shore up to the Enes–Midia line, and the islands of Imbros and Tenedos in the Aegean Sea.[81]

During the inter-Allied conferences of 1915–1916, the Triple Entente discussed the anticipated partition of the Ottoman Empire. Under the Sykes–Picot Agreement of May 10, 1916, France and Britain defined their respective spheres of influence in the Middle East. Sazonov secured a promise of a Russian zone of influence covering Ottoman Armenia and other regions inhabited by Kurds, Lazes, Alevis, and Armenians in the Ottoman Empire and Persia. The Franco-Russian agreement was signed on April 26, 1916, and the Anglo-Russian agreement on May 23.[82]

French support for the Polish cause led to pressure on Nicholas II to grant autonomy to Russian Poland. In May 1916, the Briand–Thomas mission presented this as a priority. On March 10, 1917, the Tsar accepted a project for full independence, although Poland was at the time under German and Austro-Hungarian occupation, which had proclaimed a "Kingdom of Poland" under their control. Nicholas II was deposed shortly thereafter during the February Revolution (March 15, 1917, Gregorian calendar), before implementing the decision.[83]

The Russian Provisional Government, initially led by Prince Georgy Lvov and later by Alexander Kerensky, framed the continuation of the war as a conflict between democracies and authoritarian empires (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire). However, it did not resolve tensions between preserving Russian unity and the aspirations of Poles, Finns, Ukrainians, and other minority groups.[84] Foreign Minister Pavel Milyukov sought to uphold former Tsarist claims to Constantinople and the Straits but faced opposition from the Petrograd Soviet. On March 14, 1917, the Soviet issued a manifesto calling for a “peace without annexations or indemnities.” On March 27, 1917, the Provisional Government adopted a declaration affirming its commitment to its allies while renouncing expansionist objectives.[85][86]

The October Revolution of November 1917 led to a shift in Russian policy. The Bolshevik government, led by Lenin, declared its intention to withdraw from the war and initiated negotiations with the Central Powers. It published the diplomatic correspondence of the previous regime, denounced the goals of what it termed an "imperialist war," and signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany and Austria-Hungary on March 3, 1918.[87]

France

[edit]Two priorities: Alsace–Lorraine and ending the Prussian Threat

[edit]

France’s war aims evolved throughout the conflict. Before the war, figures such as President Raymond Poincaré and Minister Théophile Delcassé favored weakening German power or reconsidering German unification, though they refrained from expressing these goals publicly.[88] After the outbreak of war, the union sacrée of political parties prioritized the recovery of Alsace–Lorraine, lost in 1871. On 20 September 1914, the Council of Ministers defined two objectives: the evacuation of French territory, including Alsace–Lorraine, and, in coordination with the Russian Empire, ending the dominance of Prussian militarism.[89] Royalist figures, such as historian Jacques Bainville, advocated for the return of Sarrelouis and Landau, former French territories lost in 1815. Conversely, socialist leaders like Pierre Renaudel opposed territorial annexations.[90] While censorship generally restricted public debate on war aims, some publications proposing the division of Germany—such as restoring South German states and Hanover—were permitted.[91]

Economic war aims

[edit]In addition to territorial objectives, French governments during the war sought to establish economic goals aimed at weakening the German Empire. In 1915, expert committees led by Jules Siegfried and Louis Barthou explored options beyond the recovery of Alsace-Lorraine, including potential French control over the Saar coal mines and the iron mines of Luxembourg, which was a neutral country occupied by Germany. A pro-French party in Luxembourg, supported by several French deputies, advocated for the annexation of the Grand Duchy to France.[92] Étienne Clémentel, Minister of Commerce and Industry from 1915 to the end of the war, worked on organizing the wartime economy and preparing for the postwar period. He proposed a model of “organized liberalism” that included a postwar customs union among France, Belgium, and Italy, excluding Germany. This proposal was opposed by heavy industry and banking sectors with prewar economic ties to Germany and Austria-Hungary, but received more support from small and medium-sized enterprises. Plans to control international raw materials markets in cooperation with Britain aimed to deprive Germany of access to essential resources.[93] The Inter-Allied Economic Conference of June 1916 partially adopted these measures for the duration of the war. However, Belgium, Italy, and Russia were less supportive of continuing Germany’s economic exclusion after the conflict, whereas Britain, departing from its usual free trade policy, showed greater openness to sanctions, some of which were later incorporated into the Treaty of Versailles.[94]

Peace conditions

[edit]In August 1916, President Raymond Poincaré requested that Generalissimo Joseph Joffre draft a document outlining potential armistice terms. In addition to the recovery of Alsace-Lorraine, Joffre proposed the annexation of parts of the Saar and the Palatinate, including Sarrelouis and Landau, as well as two bridgeheads on the right bank of the Rhine. He also suggested the creation of an autonomous Rhineland state, to be occupied and administered by France for 31 years, with the option of annexation through a plebiscite.[95] The left bank of the Rhine had previously been part of France during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods, and Rhinelanders were viewed as culturally closer to Republican France than to Prussia.[96]

Despite the heavy toll of the Battle of Verdun and the Franco-British offensive on the Somme, a confidential meeting on France’s war aims took place on October 7, 1916. Antonin Dubost, President of the Senate, and Paul Deschanel, President of the Chamber of Deputies, supported annexing the left bank of the Rhine. Minister Léon Bourgeois opposed annexation but favored a prolonged occupation and the possible establishment of an independent Rhineland state. Poincaré and Prime Minister Aristide Briand did not take a definitive position. Socialist ministers Albert Thomas, Jules Guesde, and Marcel Sembat were excluded from these discussions and from a subsequent meeting held from 4 to 7 January 1917. They later indicated support only for the recovery of Alsace-Lorraine, while not excluding the need for guarantees.[97] In November 1916, internal correspondence among senior officials at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs outlined France’s intended positions for upcoming inter-Allied conferences. These included the recovery of Alsace-Lorraine, expansion into parts of the Saar and Palatinate, permanent neutralization of the left bank of the Rhine, the option of self-determination for Luxembourg, acquisition of German colonial territories in Togo and Cameroon, and a substantial German indemnity. The Sykes-Picot Agreement of May 1916 had already defined France’s future interests in Asia Minor and the Levant.[98]

Following the failure of the French offensive at the Chemin des Dames in April 1917 and the Russian offensive in June, the French government reassessed its war objectives. During the conflict, French war aims were publicly addressed only once by parliamentarians, and solely in secret sessions: from 1 to 6 June 1917 before the Chamber of Deputies, and on 7 June before the Senate. In the Chamber of Deputies, Prime Minister Alexandre Ribot and his predecessor Aristide Briand denied any intention to annex German territory beyond Alsace-Lorraine, stating that the aim was limited to securing guarantees. To gain the support of socialist deputies, they proposed the occupation of the Rhineland by an inter-Allied force and the establishment of a League of Nations to ensure international peace. Before the Senate, their position was more assertive, calling for the punishment of German war crimes, substantial reparations, the dismantling of German militarism, and the possible creation of an independent Rhineland state, which was not to be considered an act of conquest. The concept of a League of Nations was not discussed in the Senate session.[99]

A European balance favorable to France

[edit]France sought to present its involvement in the war as a defense of international law, the European balance of power, and oppressed nations, while also pursuing its national interests. Alongside the United Kingdom, it emphasized the liberation of invaded countries such as Belgium and Serbia, and discreetly supported Serbian claims over the South Slavic regions of Austria-Hungary. This position conflicted at times with efforts to gain the support of neutral Italy and Bulgaria until 1915.[100] France supported Polish nationalism and pressured Russia to grant broad autonomy to Poland. In May 1916, the Briand-Thomas mission prioritized this demand. Tsar Nicholas II signed a declaration of Polish independence on 10 March 1917, shortly before his overthrow in the February Revolution.[101] A minority of French elites—including segments of the nobility, conservative Catholic circles, and some business interests—favored preserving Austria-Hungary as a counterweight to Prussia.[102] Support for Central European nationalities was found around Paul Painlevé and the Central Office for Nationalities, founded in 1911, which considered the possibility of transforming Austria-Hungary into a Slavic-majority confederation.[103] From February 1917, in response to the prospect of a German-dominated Mitteleuropa, France supported Roman Dmowski’s Greater Poland project, which included Lithuania and part of Ukraine. In April 1918, Albert Thomas and Henri Franklin Bouillon attended a congress in Rome in support of the nationalities of Austria-Hungary. In May 1918, France recognized the Czechoslovak National Council led by Edvard Beneš. However, to maintain its alliance with Italy, France was hesitant until late in the war to endorse the creation of a Serbian-dominated Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[104]

The armistices of 1918 allowed France to establish borders favorable to its Central European allies—Poland, Romania, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia—and to impose strict conditions on Germany. These measures were often contrary to the principle of national self-determination outlined in Wilson's Fourteen Points and did not result in a lasting peace.[105]

Serbia

[edit]The objective was to acquire Bosnia-Herzegovina from Austria-Hungary and to annex the provinces of Vojvodina, Banat, the Kingdoms of Croatia-Slavonia and Dalmatia (populated by Serbo-Croats), and the Duchy of Carniola (populated by Slovenes), with the aim of uniting them into a South Slavic state, supported by the Kingdom of Montenegro.[106]

Greece

[edit]The division of Greece into Venizelist and Monarchist camps did not prevent both sides from pursuing a shared objective: the realization of the "Great Idea," which involved Greek control over Eastern Thrace, the Dardanelles Strait, Constantinople, Smyrna, and its surrounding territory.[107] While united in this goal, they differed on the approach. During the war, Elefthérios Venizélos supported unconditional alignment with the Allies, believing the conflict would inevitably end in the defeat of the Central Powers. Constantine I, by contrast, sought to achieve the same objectives while minimizing risks to the country.[108]

From Constantine I’s perspective, Greece would not have been able to maintain a front against both the Bulgarians and the Ottomans, despite Allied promises of assistance. The Austro-Hungarian conquest of Serbia in 1915 reinforced his stance.[109] He declined to participate in the Gallipoli campaign, anticipating strong Ottoman resistance and opposing the prospect of Allied control over the Straits and Constantinople, which he believed should be reserved for Greece.[110]

Following the Turkish victory over British, Australian, and New Zealand forces in 1916, Constantine's decision was seen as prudent and increased his domestic standing.[109] However, his neutral position did not persist; he was eventually compelled to abdicate, and the Venizelist administration brought Greece into the Entente camp in 1917. In 1919, Greece’s alignment was recognized with the validation of its mandate over Eastern Thrace and the Smyrna region.[110]

United States

[edit]The American war aims were outlined in President Woodrow Wilson’s “Fourteen Points,” presented in a speech to the United States Congress on January 8, 1918.[111]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Huber, Ernst Rudolf (1978). "Aus annexionistischen Kriegszielen kann, weder für die eine noch für die andere Seite der Vorwurf abgeleitet werden, dass sie den Krieg, von seinem Grund her geurteilt, als Eroberungskrieg begonnen hätte" [From annexationist war aims, neither one side nor the other can be accused of having started the war, judged from its very foundation, as a war of conquest.]. Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte seit 1789 [German constitutional history since 1789] (in German). Vol. 5: Weltkrieg, Revolution und Reichserneuerung 1914–1919. Stuttgart. p. 218.

- ^ Malone, Gifford (1963). "War Aims toward Germany". Russian Diplomacy and Eastern Europe 1914–1917. New York: King's Crown Press. p. 124.

- ^ Hölzle, Erwin (1975). Die Selbstentmachtung Europas. Das Experiment des Friedens vor und im Ersten Weltkrieg [Europe's Self-Disempowerment: The Experiment of Peace before and during World War I] (in German). Göttingen/Frankfurt am Main/Zürich. p. 484.

- ^ Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste (2002). La Grande Guerre des Français 1914-1918 [The Great French War 1914-1918] (in German). Perrin. p. 279.

- ^ Robbins, Keith (1984). The First World War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-19-280318-4. OCLC 59498695. Retrieved July 31, 2025.

- ^ "Die Tatsache, dass Grenzverschiebungen im Zeitalter der Massenkriege, der modernen Transportmittel und der Flugzeuge nur noch begrenzte militärische Bedeutung haben, war nicht einmal den Fachmilitärs geläufig" [The fact that border shifts have only limited military significance in the age of mass wars, modern means of transport and aircraft was not even known to military experts]. Staatskunst und Kriegshandwerk : Das Problem Des "Militarismus" in Deutschland [Statecraft and Warfare: The Problem of "Militarism" in Germany] (in German). Vol. 3: Die Tragödie der Staatskunst. Bethmann Hollweg als Kriegskanzler (1914–1917). Munich: R. Oldenbourg. 1964. p. 35.

- ^ Janßen, Karl-Heinz (1984). "Gerhard Ritter: A Patriotic Historian's Justification". The origins of the First World War : great power rivalry and German war aims (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. pp. 302f. ISBN 978-0-333-37298-2. OCLC 972851123.

- ^ Huber 1978, p. 218

- ^ Kielmansegg, Peter Graf (1968). Deutschland und der Erste Weltkrieg [Germany and the First World War] (in German). Francfort-sur-le-Main: Klett-Cotta /J. G. Cotta'sche Buchhandlung Nachfo. p. 213.

- ^ Fischer, Fritz (1977). "Deutsche Kriegsziele. Revolutionierung und Separatfrieden im Osten 1914–18" [German War Aims: Revolution and Separate Peace in the East, 1914–18]. Der Erste Weltkrieg und das deutsche Geschichtsbild. Beiträge zur Bewältigung eines historischen Tabus [The First World War and the German View of History: Contributions to Overcoming a Historical Taboo] (in German). Düsseldorf: Droste Verlag GmbH. p. 153.

- ^ a b Mommsen, Wolfgang (1969). Das Zeitalter des Imperialismus [The Age of Imperialism] (in German). Francfort-sur-le-Main: BiblioBazaar. pp. 302f.

- ^ a b Poidevin, Raymond (1972). L'Allemagne de Guillaume II à Hindenburg, 1900-1933 [Germany from Wilhelm II to Hindenburg, 1900-1933] (in French). Paris: Richelieu. p. 194. OCLC 1049274521.

- ^ Cartarius, Ulrich (1982). Deutschland im Ersten Weltkrieg. Texte und Dokumente 1914–1918 [Germany in the First World War: Texts and Documents 1914–1918] (in German). Munich: dtv Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG. pp. 181f.

- ^ Mommsen, Wolfgang (2004). Max Weber und die deutsche Politik 1890-1920 [Max Weber and German Politics 1890-1920] (in German). Mohr Siebeck. p. 236.

- ^ Poidevin 1972, p. 198

- ^ Poidevin 1972, p. 195

- ^ Graf Kielmansegg, Peter (1968). Deutschland und der Erste Weltkrieg [Germany and the First World War] (in German). Francfort-sur-le-Main: Klett-Cotta /J. G. Cotta'sche Buchhandlung Nachfo. p. 224.

- ^ Fischer, Fritz (1968). Germany's Aims in the First World War. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0393097986.

- ^ Fischer 1968, p. 125ff

- ^ Schöllgen, Gregor (2000). Das Zeitalter des Imperialismus [The Age of Imperialism] (in German). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. p. 86.

- ^ Czernin, Ottokar (1919). Im Weltkriege [In World War] (in German). Berlin/Wien: University of Michigan Library. p. 96.

- ^ Conze, Werner (1958). Polnische Nation und Deutsche Politik im Ersten Weltkrieg [Polish nation and German politics in the First World War] (in German). Graz/Köln: Böhlau Verlag. p. 319.

- ^ Fischer 1968, pp. 351–356

- ^ Bihl, Wolfdieter (1991). Deutsche Quellen zur Geschichte des Ersten Weltkrieges [German sources on the history of the First World War] (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. pp. 58f.

- ^ Volkmann, Erich (1929). Die Annexionsfragen des Weltkrieges. Das Werk des Untersuchungsausschusses der Verfassungsgebenden Deutschen Nationalversammlung und des Deutschen Reichstages 1919–1928. Vierte Reihe. Die Ursachen des Deutschen Zusammenbruches im Jahre 1918. Zweite Abteilung. Der innere Zusammenbruch. 12. Bd., 1. Halbbd. Gutachten des Sachverständigen Volkmann [The Annexation Issues of the World War. The Work of the Investigative Committee of the Constituent German National Assembly and the German Reichstag, 1919–1928. Fourth Series. The Causes of the German Collapse in 1918. Second Section. The Internal Collapse. Vol. 12, Half Vol. Report by the Expert Volkmann.] (in German). Berlin. pp. 35 & 166.

- ^ Zévaès, Alexandre (1923). Histoire des partis socialistes en France. Le parti socialiste de 1904 à 1923 [History of the Socialist Parties in France. The Socialist Party from 1904 to 1923] (in French). Paris: Rivière. p. 166.

- ^ Janßen 1984, p. 302f

- ^ Bihl, Wolfdieter (1970). Österreich-Ungarn und die Friedensschlüsse von Brest-Litovsk [Austria-Hungary and the Peace of Brest-Litovsk] (in German). Wien/Köln/Graz: Wien, Köln, Graz, Böhlau. p. 118.

- ^ Fischer 1968, p. 202

- ^ Janßen 1984, p. 359

- ^ Fischer, Fritz (1964). Griff nach der Weltmacht. Die Kriegszielpolitik des kaiserlichen Deutschland 1914/18 [Grasping for World Power: Imperial Germany's War Aims 1914/18] (in German). Düsseldorf: Droste Verlag GmbH. p. 674.

- ^ Baumgart, Winfried (1966). Deutsche Ostpolitik 1918. Von Brest-Litowsk bis zum Ende des Ersten Weltkrieges [German Eastern Policy 1918: From Brest-Litovsk to the end of the First World War] (in German). Wien/München: International Affairs. p. 153.

- ^ Graf Kielmansegg 1968, p. 621

- ^ "Ritt ins Ostland" [Ride into the Eastland]. Die Selbstentmachtung Europas. Das Experiment des Friedens vor und im Ersten Weltkrieg. Tome 2 : Fragment - Vom Kontinentalkrieg zum weltweiten Krieg. Das Jahr 1917 [Europe's Self-Disempowerment. The Experiment of Peace before and during World War I. Volume 2: Fragment - From Continental War to Global War. The Year 1917] (in German). Vol. 2. Göttingen/Frankfurt am Main/Zürich. 1978. p. 44.

- ^ Hillgruber, Andreas (1979). Deutschlands Rolle in der Vorgeschichte der beiden Weltkriege [Germany's role in the prehistory of the two world wars] (in German). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 62ff.

- ^ Lee, Marshall; Michalka, Wolfgang (1987). German Foreign Policy 1917-1933. Continuity or Break?. Leamington Spa/Hamburg/New York. p. 12.

- ^ Volkmann 1929, pp. 16 & 20

- ^ Graf Kielmansegg 1968, p. 212

- ^ Graf Lynar, Wilhelm (1964). Deutsche Kriegsziele 1914-1918. Eine Diskussion [German War Aims 1914-1918: A Discussion] (in German). Frankfurt am Main/Berlin: Ullstein Bücher. p. 13.

- ^ Schwabe, Klaus (1969). Wissenschaft und Kriegsmoral. Die deutschen Hochschullehrer und die politischen Grundlagen des Ersten Weltkrieges [Science and War Morality: German University Professors and the Political Foundations of the First World War] (in German). Göttingen/Zürich/Frankfurt am Main: Musterschmidt-Verlag. p. 178.

- ^ Hillgruber, Andreas (1981). "Großmachtpolitik und Weltmachtstreben Deutschlands" [Germany's great power politics and aspirations for world power]. Ploetz: Geschichte der Weltkriege. Mächte, Ereignisse, Entwicklungen 1900-1945 [Ploetz: History of the World Wars: Powers, Events, Developments 1900-1945] (in German). Freiburg/Würzburg: Ploetz. pp. 153–162.

- ^ a b Hallgarten, George W. F. (1969). Das Schicksal des Imperialismus im 20. Jahrhundert. Drei Abhandlungen über Kriegsursachen in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart [The Fate of Imperialism in the 20th Century: Three Essays on the Causes of War, Past and Present] (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Hallgarten, George W. F. European Publishers' Office. p. 57.

- ^ Fischer 1977, Kontinuität des Irrtums

- ^ Wehler, Hans-Ulrich. Das Deutsche Kaiserreich 1871-1918 [The German Empire 1871-1918] (in German). Vol. 9. Göttingen: 1977. p. 207.

- ^ Lee & Michalka 1987, p. 15

- ^ Schöllgen, Gregor (1981). "Fischer-Kontroverse" und Kontinuitätsproblem. Deutsche Kriegsziele im Zeitalter der Weltkriege" [Fischer Controversy and the Continuity Problem: German War Aims in the Age of World Wars]. Ploetz: Geschichte der Weltkriege. Mächte, Ereignisse, Entwicklungen 1900-1945 [Ploetz: History of the World Wars: Powers, Events, Developments 1900-1945] (in German). Freiburg/Würzburg: Ploetz. pp. 174 et seq.

- ^ Farrar, L (1978). Divide and conquer : German efforts to conclude a separate peace, 1914-1918. East European monographs. Boulder New York. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-914710-38-7. OCLC 263542016.

- ^ Geiss, Imanuel (1973). "Kurt Riezler und der Erste Weltkrieg" [Kurt Riezler and the First World War]. Deutschland in der Weltpolitik des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts [Germany in World Politics of the 19th and 20th Centuries] (in German). Düsseldorf: Bertelsmann. p. 414.

- ^ Mann, Golo (1964). "Der Griff nach der Weltmacht" [The grasp for world power]. Deutsche Kriegsziele 1914-1918. Eine Diskussion [German War Aims 1914-1918: A Discussion] (in German). Frankfurt am Main/Berlin: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. pp. 83–193.

- ^ Herzfeld, Hans (1960). "Zur deutschen Politik im ersten Weltkriege. Kontinuität oder permanente Krise?" [On German policy during the First World War: Continuity or permanent crisis?]. Historische Zeitschrift [Historical Journal] (in German). pp. 67–82.

- ^ Neck, Rudolf (1962). "Kriegszielpolitik im Ersten Weltkrieg" [War aims policy in the First World War]. Mitteilungen des Österreichischen Staatsarchivs [Communications from the Austrian State Archives] (in German). pp. 565–576.

- ^ Böhme, Helmut (1973). "Die deutsche Kriegszielpolitik in Finnland im Jahre 1918" [German war aims policy in Finland in 1918]. Wendt: Deutschland in der Weltpolitik des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts [Wendt: Germany in World Politics of the 19th and 20th Centuries] (in German). Düsseldorf: Bertelsmann. pp. 377–396.

- ^ Hillgruber, Andreas (1979). Deutschlands Rolle in der Vorgeschichte der beiden Weltkriege [Germany's role in the prehistory of the two world wars] (in German). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 58 & 65.

- ^ Geiss, Imanuel (1960). Der polnische Grenzstreifen 1914-1918. Ein Beitrag zur deutschen Kriegszielpolitik im Ersten Weltkrieg [The Polish Border Strip 1914–1918: A Contribution to German War Aims in the First World War] (in German). Lübeck/Hamburg: Oxford University Press. p. 149.

- ^ Nipperdey, Thomas (1978). "1933 und die Kontinuität der deutschen Geschichte" [1933 and the continuity of German history]. Historische Zeitschrift [Historical Journal] (in German). pp. 86–111.

- ^ Hillgruber, Andreas (1981). "Großmachtpolitik und Weltmachtstreben Deutschlands" [Germany's great power politics and aspirations for world power]. Ploetz: Geschichte der Weltkriege. Mächte, Ereignisse, Entwicklungen 1900-1945 [Ploetz: History of the World Wars: Powers, Events, Developments 1900-1945] (in German). Freiburg/Würzburg: Ploetz. pp. 153–162.

- ^ Geiss, Imanuel (1972). "Die Fischer-Kontroverse. Ein kritischer Beitrag zum Verhältnis zwischen Historiographie und Politik in der Bundesrepublik" [The Fischer Controversy: A Critical Contribution to the Relationship between Historiography and Politics in the Federal Republic of Germany]. Studien über Geschichte und Geschichtswissenschaft [Studies on history and historiography] (in German). Frankfurt am Main. pp. 108–198.

- ^ Williamson, Samuel (1991). Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War. Basingstoke: Verlag Macmillan. p. 211.

- ^ Komjáthy, Miklós (1966). Protokolle des Gemeinsamen Ministerrates der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie (1914–1918) [Minutes of the Joint Council of Ministers of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy (1914–1918)] (in German). Budapest: Akadémiai kiadé. pp. 352 et seq.

- ^ Cornwall, M. (2000). The Undermining of Austria-Hungary: The Battle for Hearts and Minds. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0312231514.

- ^ Komjáthy 1966, p. 353

- ^ Komjáthy 1966, p. 355

- ^ Galántai, József (1989). Hungary in the First World War. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiado. p. 155. ISBN 978-963-05-4878-6. OCLC 910516244.

- ^ Komjáthy 1966, p. 356

- ^ a b MacMillan, Margaret (2013). The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. Random House. ISBN 978-1400068555.

- ^ Rothschild, Joseph (1974). East Central Europe between the Two World Wars. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-95350-2. JSTOR j.ctvcwnm8p. Retrieved August 1, 2025.

- ^ Komjáthy 1966, p. 358

- ^ Djokić, Dejan (2023). A Concise History of Serbia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107630215.

- ^ Mommsen, Wolfgang J (1982). Theories of Imperialism. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226533964.

- ^ Martin, Louise (June 11, 2021). "Les guerres des Balkans (1912-1913) : de l'Europe des nations à la Première Guerre mondiale" [The Balkan Wars (1912-1913): From the Europe of Nations to the First World War]. Les clés Moyen-Orient (in French). Retrieved August 1, 2025.

- ^ Opfer, Björn (2005). Im Schatten des Krieges. Besatzung oder Anschluss. Befreiung oder Unterdrückung? Eine komparative Untersuchung über die bulgarische Herrschaft in Vardar-Makedonien 1915–1918 und 1941–1944 [In the Shadow of War. Occupation or Anschluss. Liberation or Oppression? A Comparative Study of Bulgarian Rule in Vardar Macedonia 1915–1918 and 1941–1944] (in German). p. 46.

- ^ Friedrich, Wolfgang-Uwe (1985). Bulgarien und die Mächte 1913–1915. Ein Beitrag zur Weltkriegs- und Imperialismusgeschichte [Bulgaria and the Powers 1913–1915: A Contribution to World War and Imperial History] (in German). Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 242, 245, 288 & 323.

- ^ Nicollet 2021, pp. 231–235

- ^ Nicollet 2021, pp. 238–240

- ^ Opfer 2005, p. 53

- ^ Bihl, Wolfdieter (1992). Die Kaukasuspolitik der Mittelmächte. Teil 2: Die Zeit der versuchten kaukasischen Staatlichkeit (1917–1918) [The Caucasus Policy of the Central Powers. Part 2: The Period of Attempted Caucasian Statehood (1917–1918)] (in German). p. 267.

- ^ Stevenson, David (2005). Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465081851.

- ^ Howard, Michael (2007). The First World War: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199205592.

- ^ Figes 1998, pp. 327–330.

- ^ Sumpf 2014, pp. 300–302

- ^ McMeekin, Sean (2011). The Russian Origins of the First World War. Harvard University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-674-06320-4. Retrieved August 1, 2025.

- ^ Ternon, Yves (2002). Empire ottoman : le déclin, la chute, l'effacement [Ottoman Empire: Decline, Fall, and Erasure]. Le Félin poche (in French). Paris: Félin.

- ^ Sumpf 2014, pp. 305–306

- ^ Figes 1998, pp. 472–479

- ^ Jevakhoff, Alexandre (2017). La guerre civile russe (1917-1922) [The Russian Civil War (1917-1922)] (in French). Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-08145-4. Retrieved August 1, 2025.

- ^ Figes 1998, pp. 482–484

- ^ Carr, Edward Hallett (1985). The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917-1923. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393301953.

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 22–28 & 35–36

- ^ Soutou 2015, p. 93

- ^ Soutou 2015, p. 108

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 169–171

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 103–108

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 163–165

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 165–166

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 109–110

- ^ Soutou 2015, p. 112

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 110–112

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 115–121

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 220–223

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 74–78

- ^ Sumpf, Alexandre (2014). La Grande guerre oubliée : Russie, 1914-1918 [The Forgotten Great War: Russia, 1914-1918] (in French). Paris: Éditions Perrin. pp. 305–306. ISBN 978-2-262-04045-1.

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 171–173

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 227–229

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 261–272

- ^ Soutou 2015, pp. 310–312

- ^ Banac, Ivo (1984). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-0193-1. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctvrf8bft. Retrieved July 1, 2025.

- ^ Clogg, Richard (2002). A Concise History of Greece (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521004794.

- ^ Koliopoulos, John S. (2009). Modern Greece: A History since 1821. 2009. ISBN 978-1405186810.

- ^ a b Dakin, Douglas (1972). The unification of Greece, 1770-1923. Benn. ISBN 978-0510263119.

- ^ a b Llewellyn-Smith, Michael (2022). Ionian Vision: Greece in Asia Minor, 1919 - 1922. Hurst. ISBN 978-1787386051.

- ^ Link, Arthur S. (1963). Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era. Harper Torch.

Bibliography

[edit]- Figes, Orlando (1998). A People's Tragedy: Russian Revolution 1891-1924. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140243642.

- Nicollet, Charlotte (2021). Ferdinand Ier de Bulgarie : Un tsar dans la tourmente des Balkans [Ferdinand I of Bulgaria: A Tsar in the Turmoil of the Balkans] (in French). Paris: CNRS. ISBN 978-2271137746. Retrieved July 31, 2025.

- Soutou, Georges-Henri (2015). La grande illusion : Quand la France perdait la paix [The Great Illusion: When France Lost the Peace] (in French). Paris: Tallandier. ISBN 979-1021010185.