German Antarctic Expedition (1938–1939)

The German Antarctic Expedition (1938–1939), led by German Navy captain Alfred Ritscher (1879–1963), was the third official Antarctic expedition of the German Reich, by order of the "Commissioner for the Four Year Plan" Hermann Göring. Prussian State Councilor Helmuth Wohlthat was mandated with planning and preparation.

The expedition's main objective was of economic nature, in particular the establishment of a whaling station and the acquisition of fishing grounds for a German whaling fleet in order to reduce the Reich's dependence on the import of industrial oils, fats and dietary fats. Preparations took place under strict secrecy as the enterprise was also tasked to make a feasibility assessment for a future occupation of Antarctic territory in the region between 20 ° West and 20 ° East.[1][2]

Background

[edit]Like many other countries, Germany sent expeditions to the Antarctic region in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most of which were scientific. The late 19th century expeditions to the Southern Ocean, South Georgia, the Kerguelen Islands, and the Crozet Islands were astronomical, meteorological, and hydrological, mostly in close collaboration with scientific teams from other countries. As the 19th century ended, Germany began to focus on Antarctica.[citation needed]

The first German expedition to Antarctica was the Gauss expedition from 1901 to 1903. Led by Arctic veteran and geology professor Erich von Drygalski, this was the second expedition to use a hot-air balloon in Antarctica. It also found and named Kaiser Wilhelm II Land. The second German Antarctic expedition (1911–1912) was led by Wilhelm Filchner with a goal of crossing Antarctica to learn if it was one piece of land. As happened with other such early attempts, the crossing failed before it even began. The expedition discovered and named the Luitpold Coast and the Filchner Ice Shelf. A German whaling fleet was put to sea in 1937 and, upon its successful return in early 1938, plans for a third German Antarctic expedition were drawn up.[3]

Preparations

[edit]In July 1938, Captain Alfred Ritscher received a mandate to launch preparations for an Antarctic expedition and within a few months he managed to bring about logistics, equipment and organizational measures for a topographical and marine survey expedition. Whale oil was then the most important raw material for the production of margarine and soap in Germany and the country was the second largest purchaser of Norwegian whale oil, importing some 200,000 tons annually. Dependence on imports and the forthcoming war was considered to put too much strain on Germany's foreign currency reserves. Supported by whaling expert Otto Kraul marine explorations were to be undertaken in order to set up a base for a whaling fleet and aerial photo surveys were to be carried out to map territory.

With only six months available for preparatory work, Ritscher had to rely on the antiquated MS Schwabenland ship and aircraft of Deutsche Lufthansa's Atlantic Service, with which a scientific program along the coast was to be carried out and retrieve biologic, meteorologic, oceanographic and geomagnetic studies. By applying modern aerophotogrammetric methods, Aerial surveys of the unknown Antarctic hinterlands were to be carried out with two Dornier Do J II seaplanes, named Boreas and Passat, that had to be launched via a steam catapult on the MS Schwabenland expedition ship. After urgent repairs on the ship and the two seaplanes, the crew of 82 members in total, left Hamburg on December 17, 1938.[3]

Expedition

[edit]

The Expedition reached the Princess Martha Coast on January 19, 1939, and was active along the Queen Maud Land coast from 19 January to 15 February 1939. In seven survey flights between January 20 and February 5, 1939, an area of approx. 350.000 km2 (135.136 sq mi) was photogrammetrically mapped. Previously unknown ice-free mountain ranges, several small ice-free lakes were discovered in the hinterland. The ice-free Schirmacher Oasis, which now hosts the Maitri and Novolazarevskaya research stations, was spotted from the air by the pilot Richard Schirmacher (who named it after himself).

At the turning points of the flight polygons, 1.2 m (3.9 ft) long aluminum arrows, with 30 cm (12 in) steel cones and three upper stabilizer wings embossed with swastikas were supposedly dropped in order to establish German claims to ownership (which, however, was never raised). Through flight complications, those marker were only dropped once.[4] During an additional eight special flights, in which Ritscher also took part, particularly interesting regions were filmed and taken with color photos. The team flew over an area of about 600.000 km2 (231.661 sq mi).

Around 11,600 aerial photographs were taken. Biological investigations were carried out on board the Schwabenland and on the sea ice on the coast. However, the insufficient equipment did not allow sled expeditions to the ice shelf or landings of the flying boats in the mountains. All explorations were carried out without a single member of the expedition having entered the inner territory.[5]

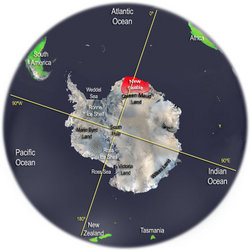

The region between 10 ° W and 15 ° E was named New Swabia (Neuschwabenland) by the expedition leader. In the meantime, the Norwegian government had found out about the German Antarctic activities after the wife of the deputy expedition leader Ernst Herrmann had informed Norwegian geologist Adolf Hoel. On January 14, 1939, the Norwegian government declared the entire sector between 20 ° W and 45 ° E Norwegian territory (Queen Maud Land) without defining its southern extent.[6]

On February 6, 1939, the expedition embarked on its return voyage, left the coast of Antarctica and carried out oceanographic research in the vicinity of Bouvet Island and Fernando de Noronha. In addition, there was a secret military assignment to explore the islands of Trindade and Martim Vaz for use as potential future naval bases.[7][1][8] The landing crew was shipwrecked in a small bay and had to be rescued.[9] On April 11, 1939, the Schwabenland arrived in Hamburg.[10]

Scientific evaluation

[edit]Until 1942 pioneer geodesist Otto von Gruber produced detailed topographical maps of eastern New Swabia at a scale of 1: 50,000 and an overview map of all explored territories. Among the newly discovered areas were, for example, the Kraul Mountains, named after whaling expert and pilot Otto Kraul. The evaluation of the results in western New Swabia was interrupted by World War II and a large part of the 11,600 oblique aerial photographs were lost during the war. In addition to the images and maps published by Ritscher, only about 1,100 aerial photos survived the war, but these were only rediscovered and evaluated in 1982. The results of the biological, geophysical and meteorological investigations were only published after the war between 1954 and 1958. Captain Ritscher did in fact prepare another expedition with improved, lighter aircraft on skids, which however was never carried out due to the outbreak of the Second World War.[11][12]

Geographic features mapped by the expedition

[edit]

As the area was first explored by a German expedition, the name New Swabia and German names given to its geographic features are still used on many maps. Some geographic features mapped by the expedition were not named until the Norwegian-British-Swedish Antarctic Expedition (NBSAE) of 1949–1952, led by John Schjelderup Giæver. Others were only named after they were remapped from aerial photos taken by the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition of 1958–1959.[13][14][15][16]

The exact location of objects in italics could not yet be determined because the position was given too imprecisely in the expedition report due to navigation problems with the aircraft, and most of the aerial photographs that would have allowed identification were lost during World War II. The names of objects that could be clearly located were used in the Norwegian translation of the topographical map Dronning Maud Land 1:250,000 published by the Norwegian Polar Institute in 1966.

| Name | Name on the Norwegian Map | Position (Informationen in the "Bundesanzeiger") | Named after / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander-von-Humboldt-Mountains | Humboldtfjella | 71° 24′–72° S, 11°–12° O | Alexander von Humboldt |

| Humboldt Basin | Humboldtsøkket | Near the eastern border of the Alexander-von-Humboldt-Mountains | Alexander von Humboldt |

| Altar | Altaret | 71° 36′ S, 11° 18′ O | distinctive mountain shape |

| Amelang Plateau | Ladfjella | 74° S, 6° 12′–6° 30′ W | Herbert Amelang, 1. Officer of the "Schwabenland“ |

| Am Überlauf (At the Overflow) | Grautrenna | Easterly to the Eckhörner (Corner Horns) | glaciated pass |

| Barkley Mountains | Barkleyfjella | 72° 48′ S, 1° 30′–0° 48′ O | Erich Barkley (1912–1944), biologist |

| Bastion | Bastionen | 71° 18′ S, 13° 36′ O | |

| Bludau Mountains | Hallgrenskarvet und Heksegryta | Part Iof a 150 km mountain range 72° 42′ S, 3° 30′ W und 74° S, 5° W | Josef Bludau (1889–1967), ships surgeon |

| Mount Bolle | 72° 18′ S, 6° 30′ O | Herbert Bolle, Deutsche Lufthansa, foreman of the aircraft assemblers | |

| Boreas | Boreas | Dornier Wal D-AGAT „Boreas“ | |

| Brandt Mountain | 72° 13′ S, 1° 0′ O | Emil Brandt (* 1900), Sailor, saved an expedition member from drowning | |

| Mount Bruns | 72° 05′ S, 1° 0′ O | Herbert Bruns (* 1908), electrical engineer of the expedition ship | |

| Buddenbrock Range | 71° 42′ S, 6° O | Friedrich Freiherr von Buddenbrock, Operations Manager of Atlantic Flights at Deutsche Lufthansa | |

| Bundermann Range | Grytøyrfjellet | 71° 48′–72° S, 3° 24′ O | Max Bundermann (* 1904), aerial photographer |

| Conrad Mountains | Conradfjella | 71° 42′–72° 18′ S, 10° 30′ O | Fritz Conrad |

| Dallmann Mountains | Dallmannfjellet | 71° 42′–72° S, closely west 11° O | Eduard Dallmann |

| Drygalski Mountains | Drygalskifjella | 71° 6′–71° 48′ S, 7° 6′–9° 30′ O[17] | Erich von Drygalski |

| Eckhörner (Corner Horns) | Hjørnehorna | North end of the Alexander-von-Humboldt-Gebirges | markante Bergform |

| Filchner Mountains | Filchnerfjella | 71° 6′–71° 48′ S, 7° 6′–9° 30′ O[17] | Wilhelm Filchner |

| Gablenz-Ridge | 72°–72° 18′ S, 5° O | Carl August von Gablenz | |

| Gburek Peaks | Gburektoppane | 72° 42′ S, 0° 48′–1° 10′ W | Leo Gburek (1910–1941), geomagnetist |

| Geßner Peak | Gessnertind | 71° 54′ S, 6° 54′ O | Wilhelm Geßner (1890–1945), Director of Hansa Luftbild |

| Gneiskopf Peak | Gneisskolten | 71° 54′ S, 12° 12′ O | promintent peak |

| Gockel-Ridge | Vorrkulten | 73° 12′ S, 0° 12′ W | Wilhelm Gockel, meteorologist of the expedition |

| Graue Hörner (Grey Horns) | Gråhorna | Southern corner of the Petermann mountain range | |

| Gruber Mountains | Slokstallen und Petrellfjellet | 72° S, 4° O | Erich Gruber (1912–1940), radio operator on D-AGAT „Boreas“ |

| Habermehl Peak | Habermehltoppen | Westernly to the Geßnerpeak | Richard Habermehl, head of the Reich Weather Service |

| Mount Hädrich | 71° 57′ S, 6° 12′ O | Willy Hädrich, Authorized officer at Deutsche Lufthansa, responsible for the accounting of the expedition | |

| Mount Hedden | 72° 8′ S, 1° 10′ O | Karl Hedden, Sailor, saved an expedition member from drowning | |

| Herrmann Mountains | 73° S, 0°–1° O | Ernst Herrmann, geologist of the expedition | |

| In der Schüssel (In the Bowl) | Grautfatet | in the North of the Alexander-von-Humboldt-Gebirges | glaciated valley |

| Johannes Müller Ridge | Müllerkammen | Johannes Müller († 1941), Participant in the 2nd German South Polar Expedition in 1911/12, Head of the Nautical Department of the North German Lloyd | |

| Kaye Peak | Langfloget | 72° 30′ S, 4° 48′ O | Georg Kaye, Naval architect, looked after the ships of Lufthansa |

| Kleinschmidt Peak | Enden | Part of a 150 km long ridge between 72°42′ S, 3°30′ W and 74° S, 5° W | Ernst Kleinschmidt, German Maritime Observatory |

| Kottas Mountains | Milorgfjella | 74° 6′–74° 18′ S, 8° 12′–9° W | Alfred Kottas, Captain of the "Schwabenland" |

| Kraul Mountains | Vestfjella | Otto Kraul, ice pilot | |

| Krüger Mountains | Kvitskarvet | 73° 6′ S, 1° 18′ O | Walter Krüger, meteorologist of the expedition |

| Kubus | Kubus | 72° 24′ S, 7° 30′ O | distinctive mountain shape |

| Kurze Mountain Range | Kurzefjella | 72° 6′–72° 30′ S, 9° 30′–10° O | Friedrich Kurze,Vice Admiral, Head of the Nautical Department of the Naval High Command |

| Lange-Plateau | 71° 58′ S, 0° 25′ O | Heinz Lange (1908–1943), meteorlogical assistant | |

| Loesener Plateau | Skorvetangen, Hamarskorvene und Kvithamaren | 72° S, 4° 18′ O | Kurt Loesener, airplane mechanic of D-AGAT „Boreas“ |

| Lose Plateau | Lausflæet | distinctive mountain shape | |

| Luz Ridge | 72°–72° 18′ S, 5° 30′ O | Martin Luz, commercial director at the German Lufthansa | |

| Mayr Mountain Range | Jutulsessen | 72°–72° 18′ S, 3° 24′ O | Rudolf Mayr, Pilot of D-ALOX „Passat“ |

| Matterhorn | Ulvetanna | highest peak in den Drygalski-Mountains | distinctive mountain shape |

| Mentzel Mountains | Mentzelfjellet | 71° 18′ S, 13° 42′ O | Rudolf Mentzel |

| Mühlig-Hofmann Mountains | Mühlig-Hofmannfjella | 71° 48′–72° 36′ S, 3° O | Albert Mühlig-Hofmann |

| Neumayer steep face | Neumayerskarvet | Georg von Neumayer | |

| New Swabia | Expeditionship „Schwabenland“ | ||

| Northwestern Island | Nordvestøya | Northend of the Alexander-von-Humboldt-Gebirges | island-like nunatak group |

| Eastern Hochfeld | Austre Høgskeidet | between the southern and central sections of the Petermann range | Ice tounge |

| Obersee (Upper Lake) | Øvresjøen | 71° 12′ S, 13° 42′ O | frozen lake |

| Passat | Passat | Donier Wal D-ALOX | |

| Paulsen Mountains | Brattskarvet, Vendeholten und Vendehø | 72° 24′ S, 1° 30′ O | Karl-Heinz Paulsen, oceanographer of the expedition |

| Payer Mountain group | Payerfjella | 72° 0′ S, 14° 42′ O | Julius von Payer |

| Penck Trough | Pencksøkket | Albrecht Penck | |

| Petermann Range | Petermannkjeda | Between the Alexander-Humboldt-Mountains and the „zentralen Wohlthatmassiv“ [=Otto-von-Gruber-Mountains] on 71°18′–72°9′ S | August Petermann |

| Preuschoff Ridge | Hochlinfjellet | 72° 18′–72° 30′ S, 4° 30′ O | Franz Preuschoff, airplane Mechanic of D-ALOX „Passat“ |

| Regula Mountain Range | Regulakjeda | Herbert Regula (1910–1980), I. Meteorologist of the expedition | |

| Ritscherpeak | Ritschertind | 71° 24′ S, 13° 24′ O | Alfred Ritscher |

| Ritscher Upland | Ritscherflya | Alfred Ritscher | |

| Mount Röbke | Isbrynet | Karl-Heinz Röbke (* 1909), II. Officer on the „Schwabenland“ | |

| Mount Ruhnke | Festninga | 72° 30′ S, 4° O | Herbert Ruhnke (1904–1944), Radio operator on D-ALOX „Passat“ |

| Sauter Mountain bar | Terningskarvet | 72° 36′ S, 3° 18′ O | Siegfried Sauter, aerial photographer |

| Schirmacher Ponds[18] | Schirmacher Oasis | 70° 40′ S, 11° 40′ O | Richardheinrich Schirmacher, Pilot of D-AGAT „Boreas“ |

| Schneider-Riegel | 73° 42′ S, 3° 18′ W | Hans Schneider, Head of the Sea-Flight Department of the German Maritime Observatory and Professor of Meteorology | |

| Schubertpeak | Høgfonna und Ovbratten | Part of a 150 km long ridge between 72°42′ S, 3°30′ W und 74° S, 5° W | Otto von Schubert, Head of the Nautical Department of the German Maritime Observatory |

| Schulz Heights | Lagfjella | 73° 42′ S, 7° 36′ W | Robert Schulz, II. Engineer on the „Schwabenland“ |

| Schicht Mountains | Sjiktberga | 71° 24′ S, 13° 12′ O | |

| Schwarze Hörner (Black horns) | Svarthorna | southern corner of the northern part of the Petermann range | distinctive mountain range |

| See Kopf (Sea-Head) | Sjøhausen | 71° 12′ S, 13° 48′ O | distinctive mountain |

| Seilkopf Mountains | Nälegga | Part of a 150 km long ridge between 72°42′ S, 3°30′ W and° S, 5° W | Heinrich Seilkopf, Head of the Sea-Flight Department of the German Maritime Observatory and Professor of Meteorology |

| Sphinxkopf Peak | Sfinksskolten | On the north end of the Petermann range | distinctive mountain |

| Spieß Peak | Huldreslottet | Part of a 150 km long ridge between. 72°42′ S, 3°30′ W and 74° S, 5° W | Admiral Fritz Spieß, commander of the research vessel Meteor |

| Stein Peaks | Straumsnutane | Willy Stein, Boatswain of the „Schwabenland“ | |

| Todt Mountain bar | Todtskota | 71° 18′ S, 14° 18′ O | Herbert Todt, Assistent of the expeditionleader |

| Uhligpeak | Uhligberga | Part of a 150 km long ridge between72°42′ S, 3°30′ W and 74° S, 5° W | Karl Uhlig, Leading Engineer of the „Schwabenland“ |

| Lake Untersee | Nedresjøen | 71° 18′ S, 13° 30′ O | frozen lake |

| Vorposten Peak | Forposten | 71° 24′ S, 15° 48′ O | remote nunatak |

| Western Hochfeld | Vestre Høgskeidet | glaciated plain | |

| Weyprecht Mountains | Weyprechtfjella | 72° 0′ S, 13° 30′ O | Carl Weyprecht |

| Wegener Inland Ice | Wegenerisen | Alfred Wegener | |

| Wittepeaks | Marsteinen, Valken, Krylen und Knotten | Dietrich Witte, engine attendant of the "Schwabenland“ | |

| Wohlthat Mountain Range | Wohlthatmassivet | Helmuth Wohlthat | |

| Mount Zimmermann | Zimmermannfjellet | 71° 18′ S, 13° 24′ O | Carl Zimmermann, Vice President of the German Research Foundation |

| Zuckerhut (sugar loaf) | Sukkertoppen | 71° 24′ S, 13° 30′ O | distinctive mountain shape |

| Zwiesel Mountain | Zwieselhøgda | On the southern ends of the Petermann range |

Public perception

[edit]

As a result of great secrecy and relatively little time for preparation, the enterprise escaped nearly any advanced public attention as the MS Schwabenland embarked unnoticed.

The first report of the expedition was telegraphed only during the return journey from Cape Town to Helmut Wohlthat, who published a press release on March 6, 1939. As in Great Britain the Daily Telegraph and in the USA the New York Times reported on the expedition in reference to the Norwegian occupation of the area, only the Hamburg local press took notice of the expedition's return to Germany. On May 25, 1939, the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung magazine published a small-scale map of the mountains discovered and the flight polygons without authorization by the expedition leader. The map was drawn by the aircraft mechanic Franz Preuschoff and is as such referred to as the "Preuschoff map". This map was incorporated in the 1939 1: 10,000,000 scale map of Antarctica by Australian cartographer E. P. Bayliss.

A reference to the expedition was posted in the Berlin Zoological Garden in front of the Emperor penguin enclosure. The penguins had been caught by Lufthansa flight captain Rudolf Mayr, flight mechanic Franz Preuschoff and zoologist Erich Barkley and arrived in Cuxhaven on April 12, 1939. The expedition geologist Ernst Herrmann, published the only popular science book for a wider audience for more than 60 years in 1941. Due to the lack of information during the following decades, myths and conspiracy theories eventually developed around the expedition and Neuschwabenland.[19][20]

Although Germany issued a decree about the establishment of a German Antarctic Sector called New Swabia after the expedition's return in August 1939 no official territorial claims were ever advanced for the region and were fully abandoned in 1945.[21] No whaling station or other lasting structure was built by Germany until the Georg von Neumayer Station, a research facility, established in 1981. The current Neumayer Station III is also located in the region.

New Swabia is occasionally mentioned in historical contexts, it is not an officially recognized cartographic designation today. The region is part of Queen Maud Land, administered by Norway as a dependent territory under the Antarctic Treaty System, and overseen by the Polar Affairs Department of the Ministry of Justice and the Police.[22]

Conspiracy theories

[edit]New Swabia has been the subject of conspiracy theories for decades, some of them related to Nazi UFO claims. Most assert that, in the wake of the German expedition of 1938–39, a huge military base was built there. After the war, high-ranking Nazis, scientists, and elite military units are claimed to have survived there. The US and UK have supposedly been trying to conquer the area for decades, and to have used nuclear weapons in this effort. Proponents claim the base is sustained by hot springs providing energy and warmth.[23]

The WDR radio play Neuschwabenland-Symphonie from 2012 takes up the conspiracy theories.[24]

Crew list

[edit]

The list contains all expedition members of the German Antarctic Expedition 1938/39. Under 'Remarks' it is indicated, if the participants had already taken part in any previous polar expeditions. Most of the crew members of the Schwabenland had previously served on this ship in the Atlantic service. As far as is known, all members were of German nationality.

| Name | Organization | Task | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific Personnel | ||||||

| Alfred Ritscher (1879–1963) | High Command of the Navy | Expedition leader | Participant of the Schröder-Stranz-Expedition 1912–13, Marine Aviator in World War 1 | |||

| Ernst Herrmann (1895–1970) | Teacher, Berlin | Geologist, deputy expedition leader | Private Expeditions to Spitsbergen 1937 und Greenland 1938 | |||

| Dr. Herbert Regula (1910–1980) | German Maritime Observatory | I. Meteorologist | Meteorologist on the catapult ship Westfalen 1933–34 | |||

| Heinz Lange (1908–1943) | Reichs Office for Weather Service | II. Meteorologist, Specialist on radiosondes | ||||

| Walter Krüger (1905–1948) | Reichs Office for Weather Service | Meteorology Assistant | Participant of the Meteor Expedition 1925–27 | |||

| Wilhelm Gockel (1908– ) | Marine Observatory Wilhelmshaven | Meteorology Assistant | ||||

| Erich Barkley (1912–1944) | Reich Institute for Fisheries, Institute for Whale catching | Biologist | Seven months in antarctic waters with the whaler C.L. Larsen 1937/38 | |||

| Leo Gburek (1910–1941) | University Leipzig, Geomagnetic Institute | Geophysicist | Two expeditions for the purpose of geomagnetic surveys to Spitsbergen in 1937 and 1938 (there he met E. Herrmann) | |||

| Karl-Heinz Paulsen (1909–1941) | University Hamburg | Oceanographer | One whaling season on Jan Wellem 1937/38 | |||

| Aviation personnel | ||||||

| Rudolf Mayr (Pilot) (1910–1991) | Lufthansa | Pilot of the Dornier-Wal airplane Passat | Pilot of Dornier-Wal Perssuak during the Danish expedition to northeast Greenland and Peary Land April–June 1938 under Lauge Koch, later chief pilot of Lufthansa[25] | |||

| Franz Preuschoff | Lufthansa | Flight engineer | Together with Mayr on the expedition to Northeast Greenland and Peary Land April–June 1938, later chief flight engineer of Lufthansa[26] | |||

| Herbert Ruhnke (1904–1944) | Lufthansa | flight radio operator | ||||

| Max Bundermann (1904– ) | Hansa Luftbild | Aerial photographer | Participant of a NSIU expedition to northeast Greenland in 1932, during which he took 2109 aerial photographs from a Lockheed Vega[27] | |||

| Richardheinrich Schirmacher | Lufthansa | Pilot of the Dornier-Wal airplane Boreas | ||||

| Kurt Loesener | Lufthansa | Flight engineer | ||||

| Erich Gruber (1912–1940) | Lufthansa | Flight radio operator | ||||

| Siegfried Sauter (1916–2008) | Hansa Luftbild | Aerial photographer | ||||

| Crew of the Schwabenland | ||||||

| Alfred Kottas (1885–1969) | Lufthansa | Captain | ||||

| Otto Kraul (1892–1972) | From Hamburg | Ice Pilot | Whaling chief on the Jan Wellem 1937/38 | |||

| Herbert Amelang | Norddeutscher Lloyd | I. Officer, Deputy Commander | ||||

| Josef Bludau (1889–1967) | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Ships surgeon | ||||

| Karl-Heinz Röbke (1909– ) | Norddeutsche Lloyd | II. Officer | As NSDAP-Member responsible for the „political reliability“ of the expedition members | |||

| Hans Werner Viereck | Norddeutscher Lloyd | III. Officer | ||||

| Vincenz Grisar | Norddeutscher Lloyd | IV. Officer | ||||

| Erich Harmsen | Deutsche Lufthansa | Ship's radio conductor | ||||

| Kurt Bojahr | Deutsche Lufthansa | Ship's radio officer | ||||

| Ludwig Müllermerstadt | Deutsche Lufthansa | Ship's radio officer | ||||

| Karl Uhlig (1885– ) | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Leading Engineer | ||||

| Robert Schulz | Norddeutscher Lloyd | II. Engineer | ||||

| Henry Maas | Norddeutscher Lloyd | III. Engineer | ||||

| Edgar Gäng | Norddeutscher Lloyd | IV. Engineer | ||||

| Hans Nielsen | Norddeutscher Lloyd | V. Engineer | ||||

| Johann Frey | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Engineer assistant | ||||

| Georg Jelschen | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Engineer assistant | ||||

| Heinz Siewert | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Engineer assistant | ||||

| Herbert Bruns (1908– ) | Atlas Werke | Electrical engineer | ||||

| Karl-Heinz Bode | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Electrician | ||||

| Herbert Bolle | Deutsche Lufthansa | Foreman | ||||

| Wilhelm Hartmann | Deutsche Lufthansa | Catapult leader | ||||

| Alfred Rücker | Deutsche Lufthansa | Manager of the flight store | ||||

| Franz Weiland | Deutsche Lufthansa | Flight mechanic | ||||

| Axel Mylius | Deutsche Lufthansa | Flight mechanic | ||||

| Wilhelm Lende | Deutsche Lufthansa | Flight mechanic | ||||

| Willy Stein | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Boatswain | ||||

| Richard Wehrend | Norddeutscher Lloyd | I. Carpenter | ||||

| Alfons Schäfer | Norddeutscher Lloyd | II. Carpenter | ||||

| Heinz Hoek | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Sailor | ||||

| Jürgen Ulpts | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Sailor | ||||

| Albert Weber | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Sailor | ||||

| Adolf Kunze | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Sailor | Took part as a sailor in the Second German Antarctic Expedition 1911/12 under Wilhelm Filchner | |||

| Karl Hedden | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Sailor | ||||

| Eugen Klenck | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Sailor | ||||

| Fritz Jedamezyk | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Sailor | ||||

| Emil Brandt (1900– ) | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Sailor | ||||

| Kurt Ohnemüller | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Sailor | ||||

| Alfred Peters | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Easy sailor | ||||

| Alex Burtscheid | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Ship's boy | ||||

| Karl-Heinz Meyer | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Ship's boy | ||||

| Walter Brinkmann | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Storeman | ||||

| Dietrich Witte | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Engine attendant | ||||

| Erich Kubacki | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Engine attendant | ||||

| Walter Dräger | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Engine attendant | ||||

| Karl Olbrich | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Assistant boiler attendant | ||||

| Georg Niemüller | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Assistant boiler attendant | ||||

| Friedrich Mathwig | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Cleaner | ||||

| Ferdinand Dunekamp | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Cleaner | ||||

| Erwin Steinmetz | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Cleaner | ||||

| Herbert Callis | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Cleaner | ||||

| Helmut Dulatschow | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Baker | ||||

| Otto Sieland | Norddeutscher Lloyd | I. Cook | ||||

| Fritz Troe | Norddeutscher Lloyd | II. Cook | ||||

| Gottfried Thole | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Cook's mate and baker | ||||

| Ferdinand Wolf | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Cook's mate and butcher | ||||

| Hans Büttner | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Kitchen boy | ||||

| Willi Reeps | Norddeutscher Lloyd | I. Steward | ||||

| Wilhelm Malyska | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Steward | ||||

| Rudolf Stawicki | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Steward | ||||

| Willi Fröhling | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Mess steward | ||||

| Johann van de Logt | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Mess steward | ||||

| Rudolf Burghard | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Mess steward | ||||

| Rolf Oswald | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Mess boy | ||||

| Johann Bates | Norddeutscher Lloyd | Mess boy | ||||

| other employees | ||||||

| Herbert Todt (1911–2003) | Employee of the expedition 1938 bis 1941 | Secretary of the Expedition | ||||

| Ilse Uhlmann (1916–1997) | Employees of the expedition | Secretary | later wife of Alfred Ritscher[28] | |||

Further reading

[edit]- The Third Reich in Antarctica, by Cornelia Lüdecke and Colin Summerhayes (The Erskine Press, 2012) ISBN 978-1852971038

- Germans in Antarctica , by Cornelia Lüdecke (Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2021) ISBN 978-3-030-40926-5

- Deutsche Forscher im Südpolarmeer , first hand account by the expedition member Ernst Herrmann (Safari-Verlag, 1941)

- Murphy, D.T. (2002). German exploration of the polar world. A history, 1870–1940 Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803232051, OCLC 48084187

See also

[edit]- First German Antarctic Expedition (1901-1903)

- Second German Antarctic Expedition (1911- 1912)

- 1938–39 German expedition to Tibet

- German Amazon-Jary-Expedition (1935-1937)

- Antarctica during World War II

- Operation Tabarin

- Operation Highjump

References

[edit]- ^ a b Eric Niiler. "Hitler Sent a Secret Expedition to Antarctica in a Hunt for Margarine Fat". A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ C. P. Summerhayes. "Hitler's Antarctic Base: The Myth and the Reality". University of Cambridge. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Luke Fater (November 6, 2019). "Hitler's Secret Antarctic Expedition for Whales". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ Lüdecke, Cornelia. Germans in Antarctica. p. 317.

- ^ Lüdecke, Cornelia (2021). Germans in the Antarctic. Springer Nature. pp. 155–. ISBN 978-3-030-40924-1.

- ^ Andrew J. Hund (14 October 2014). Antarctica and the Arctic Circle: A Geographic Encyclopedia of the Earth's Polar Regions [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 303–. ISBN 978-1-61069-393-6.

- ^ Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine: November 21, 1938, B.No. 2215/38 g. Kds. BH W V; Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde, Leipzig, Ritscher estate, File Bh1, Abt. OKM.

- ^ "Hitler's Antarctic base: the myth and the reality" Archived 13 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, by Colin Summerhayes and Peter Beeching, Polar Record, Volume 43 Issue 1, pp. 1–21. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- ^ Herrmann, Ernst (1942). Deutsche Forscher im Südpolarmeer [German Scientists in the South Polar Sea] (in German). pp. 135–141.

- ^ William James Mills (2003). Exploring Polar Frontiers: M-Z. ABC-CLIO. pp. 552–. ISBN 978-1-57607-422-0.

- ^ Cornelia Lüdecke; Colin Summerhayes (15 December 2012). The Third Reich in Antarctica: the German Antarctic Expedition, 1938-39. The Erskine Press. ISBN 978-1-72091-889-9.

- ^ Deutsche hydrographische Zeitschrift: Ergänzungsheft. Reihe B. Deutsches Hydrographisches Institut. 1980.

- ^ "Norwegian-British-Swedish Antarctic Expedition". Australian Antarctic Division. July 10, 2009. Archived from the original on October 3, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ Claude Cowan (September 20, 2002). "Norwegian-British-Swedish Antarctic Expedition, 1949-1952". Scott Polar Research Institute. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ "Norway Station 1956-1960" (PDF). Norsk Polarhistorie. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ USGS GNIS

- ^ a b Angabe für Drygalski- und Filchnerberge

- ^ Renamed to Schirmacher Oasis, after Antarctic Oasis was defines as an independent object type

- ^ Wilhelm Filchner; Alfred Kling; Erich Przybyllok (1994). To the Sixth Continent: The Second German South Polar Expedition. Bluntisham Books. ISBN 978-1-85297-038-3.

- ^ Rainer F. Buschmann; Lance Nolde (26 July 2018). The World's Oceans: Geography, History, and Environment. ABC-CLIO. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-1-4408-4352-5.

- ^ Heinz Schön (2004). Mythos Neu-Schwabenland: für Hitler am Südpol : die deutsche Antarktisexpedition 1938-39. Bonus-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-935962-05-6.

- ^ "Queen Maud Land". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ Holm Hümmler: Neuschwabenland – Verschwörung, Mythos oder Ammenmärchen? In: Skeptiker. Nr. 3, 2013, S. 100–106.

- ^ "ARD-Hörspieldatenbank". hoerspiele.dra.de. Retrieved 2021-12-19.

- ^ "Düse statt Propeller: Zeitgewinn auf allen Strecken". Lufthansa Group (in German). Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2025.

- ^ Kurzbiographie Preuschoff

- ^ Cornelia Lüdecke, Colin Summerhayes (2012), The Third Reich in Antarctica. The German Antarctic Expedition 1938-39, Eccles und Huntingdon: Erskine Press und Bluntisham Books, p. 34, ISBN 978-1-85297-103-8

- ^ Nachruf in der Zeitschrift Polarforschung (PDF; 269 kB)

External links

[edit]- Photographs of the MS Schwabenland and its seaplanes (in German)

- More photographs of the MS Schwabenland (in German)

- Erich von Drygalski and the 1901–03 German Antarctic Expedition, Scott Polar Research Institute

- Wilhelm Filchner and the 1911–12 German Antarctic Expedition, Scott Polar Research Institute

- Kartographische Arbeiten und deutsche Namengebung in Neuschwabenland, Antarktis