Rugocaudia

| Rugocaudia Temporal range: Early Cretaceous (Albian),

| |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Titanosauriformes |

| Genus: | †Rugocaudia Woodruff, 2012 |

| Type species | |

| †Rugocaudia cooneyi Woodruff, 2012

| |

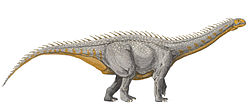

Rugocaudia is a potentially dubious genus of early titanosauriform sauropod dinosaurs known from the Early Cretaceous of Montana, United States.

Discovery and naming

[edit]Rugocaudia is known from the holotype specimen, MOR 334, a partial skeleton consisting of 18 caudal vertebrae and associated material including an isolated neural arch, tooth, chevron, and distal section of a metacarpal. It was collected from the Cloverly Formation, which dates to the Aptian or the Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous. Comparisons of the known material to contemporary sauropods (e.g. Sonorasaurus, Venenosaurus, and Paluxysaurus) suggested that its fossils represent a new taxon from the region. Rugocaudia cooneyi was described and named as a new genus and species by D.Cary Woodruff in 2012. The generic name is derived from the Latin ruga, "wrinkle" and cauda, "tail", referencing the highly rugose posterior margins of the caudal vertebrae. The specific name honors J. P. Cooney, the owner of the land on which the holotype was found.[1]

Description

[edit]Rugocaudia is a mid-sized titanosauriform sauropod. Woodruff (2012) did not publish an estimate of the animal's full size, however, he hypothesized that its tail was probably around 5 m (16 ft) in length.[1] Rubén Molina-Pérez and Asier Larramendi later estimated that the full animal was possibly around 14.1 m (46 ft) long, 3.3 m (11 ft) tall at the shoulder, and possibly weighed 6.3 tons.[2]

Rugocaudia can be distinguished from all other sauropods by the following autapomorphies: stronly procoelous centra at the end of the tail, neural spines at the front of the tail that project backwards, neural arches positioned on the back of the vertebrae, centra that are roughly as tall as they are wide, and a deep canal on the chevrons. The vertebrae bear several other distinct features, some of which are shared by other taxa, but which are synapomorphic of this taxon. They include: a very rugose texture on the vertebral condyles, two large depressions on the anteior part of the condyles on the front tail vertebrae, numerous neurovascular foramina on the margins of the condyles, a convex-upward bend in the vertebrae at the end of the tail, and centra along the middle of the tail that are square-shaped in lateral view. The genus was diagnosed based on the tail vertebrae, but the other fragmentary bones were too incomplete for them to be useful for understanding the taxon, so they were not used in the diagnosis.[1]

Classification

[edit]Woodruff (2012) did not conduct a phylogenetic analysis in his description of Rugocaudia, regarding the material as too fragmentary for such an analysis to be useful, and stating that this would only be informative if more material were to be found. However, Woodruff was able to diagnose Rugocaudia as a member of Titanosauriformes. The tail vertebrae bore several of the distinguishing features of this group including: high variability in the morphology of the caudal vertebrae, strongly procoelous posterior caudals, mid-front caudals with a concave front and flat rear, and amphicoelous vertebrae along the rear part of the tail.[1]

The fragmentary nature of the taxon has led subsequent authors to regard it as a nomen dubium;[3] later in 2012, D'Emic and Foreman noted that Woodruff's diagnosis for the taxon was largely based on anatomical characters that were not observable or present in the fossil material, characters that were also seen in other taxa, and characters related to damage in the material.[4]

Paleoenvironment

[edit]Rugocaudia was found in the Early Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of Montana. During that time, the region consisted of wide floodplains around rivers that drained into the shallow inland sea to the north and east, carrying sediment eroded from the low mountains to the west. Periodic flooding of these rivers covered the surrounding plains with new muddy sediments, creating the Cloverly Formation and burying the remains of many animals, some of which would be fossilized. Later in the Cretaceous, the shallow sea would expand to cover the entire region and would eventually split North America completely in half, forming the Western Interior Seaway.[5] Abundant fossil remains of coniferous trees suggest that these plains were covered in forests.[6] Grasses would not evolve until later in the Cretaceous, so Rugocaudia and other Early Cretaceous herbivores browsed from a variety of conifers and cycads.[7]

The most abundant herbivorous dinosaur known from the Cloverly Formation is the large iguanodont Tenontosaurus. The smaller hypsilophodont Zephyrosaurus, the nodosaurid Sauropelta, and an indeterminate ornithomimosaur were also present in the environment. The dromaeosaurid theropod Deinonychus fed upon some of these herbivores, and the sheer number of Deinonychus teeth scattered throughout the formation are a testament to its abundance.[6][5] Microvenator, a small basal oviraptorosaur, hunted smaller prey,[6][5] while the apex predators of the Cloverly was the large carcharodontosaurid theropod Acrocanthosaurus.[8] Lungfish, triconodont mammals, and several species of turtles lived in the Cloverly, while crocodilians prowled the rivers, lakes, and swamps, providing evidence of a year-round warm climate.[6][5]

See also

[edit]- 2012 in archosaur paleontology

- List of fossiliferous stratigraphic units in Montana

- List of North American dinosaurs

- List of sauropod species

- List of sauropodomorph type specimens

- List of the prehistoric life of Montana

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d D. Cary Woodruff (2012). "A new titanosauriform from the Early Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of Montana". Cretaceous Research. 36: 58–66. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2012.02.003.

- ^ Molina-Pérez, Rubén; Larramendi, Asier (29 September 2020). Dinosaur Facts and Figures: The Sauropods and Other Sauropodomorphs. Translated by Donaghey, Joan. Illustrated by Andrey Atuchin and Sante Mazzei. Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvt7x71z. ISBN 978-0-691-19069-3.

- ^ Britt, B.B.; Scheetz, R.D.; Whiting, M.F.; Wilhite, D.R. (2017). "Moabosaurus utahensis, n. gen., n. sp., A New Sauropod From The Early Cretaceous (Aptian) of North America". Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan. 32 (11): 189–243. hdl:2027.42/136227. Archived from the original on 2017-04-11. Retrieved 2017-04-10.

- ^ d'Emic, Michael D.; Foreman, Brady Z. (2012). "The beginning of the sauropod dinosaur hiatus in North America: insights from the Lower Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of Wyoming". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (4): 883–902. Bibcode:2012JVPal..32..883D. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.671204. S2CID 128486488.

- ^ a b c d Maxwell, W. Desmond. (1997). "Cloverly Formation". In Currie, Philip J.; Padian, Kevin (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 128–129. ISBN 9780122268106.

- ^ a b c d Ostrom, John H. (1970). "Stratigraphy and paleontology of the Cloverly Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of the Bighorn Basin area, Wyoming and Montana". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 35: 1–234.

- ^ Prasad, Vandana; Strömberg, Caroline A.E.; Alimohammadian, Habib; Sahni, Ashok. (2005). "Dinosaur coprolites and the early evolution of grasses and grazers". Science. 310 (5751): 1177–1180. Bibcode:2005Sci...310.1177P. doi:10.1126/science.1118806. PMID 16293759. S2CID 1816461.

- ^ D'Emic, Michael D.; Melstrom, Keegan M.; Eddy, Drew R. (2012). "Paleobiology and geographic range of the large-bodied Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus atokensis". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 333–334: 13–23. Bibcode:2012PPP...333...13D. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.03.003.