Jatha

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Sikhism |

|---|

|

A Jatha (Punjabi: ਜੱਥਾ [sg]; ਜਥੇ [pl] (Gurmukhi)) is an armed body of Sikhs[1] that has existed in Sikh tradition since 1699, the beginning of the Khalsa (Sikh martial order).[2] A Jatha basically means a group of people.[citation needed]

Etymology

[edit]The word derives from the Sanskrit word yūtha, meaning a "herd, flock, multitude, troop, band, or host".[3]

Origins

[edit]Damdami Taksal Jatha

[edit]After the creation of the Khalsa, Guru Gobind Singh is said to have created the Damdami Taksal in 1706.[citation needed] Its first Jathedar (leader) was Baba Deep Singh who died at the age of 83 by having his head severed in a battle against Durrani forces.[citation needed]

Aftermath of the death of Banda Singh Bahadur

[edit]In the Sikh tradition, a Jatha refers to a group of Sikh volunteers working together for a common cause, whether that cause is violent or peaceful.[3] The term was already in use by the first half of the 18th century amongst the Sikhs but its exact point of origin has not been traced as of yet.[3] The aftermath of the execution of Banda Singh Bahadur and persecution of the Sikhs by the Mughal authorities led to the Sikhs gathering in armed nomadic groups, termed Jathas.[3]

Each Jatha was headed by a local leader, known as a Jathedar.[3] The Jathedar was chosen based on merit alone, as only the most daring and courageous warrior of a particular band was selected for the honour.[3] Devout Sikhs of the Khalsa joined the various Jathas, which appealed to them to advance the cause of their religion and fight oppression.[3] An important selection criterion for joining a Jatha was skill in horsemanship, as cavalry tactics and guerilla warfare was vital to the fighting style of the Jathas against the far more numerous Mughal and Afghan forces.[3] Therefore, agility and maneuverability were the most critical skills that a Sikh had to master to succeed in a Jatha.[3]

The Jathas were in ordinary times independent of one another and had to depend on itself to survive, but they co-operated on missions.[3] All of the Jathas submitted to the authority of the Sarbat Khalsa and attended the annual Diwali convening in Amritsar.[3] If a Gurmata was passed by the Sarbat Khalsa, the Jathas obeyed it.[3]

Peace at Amritsar

[edit]The Mughal government made peace with the Sikhs for a short sliver of time between 1733 and 1735 and allowed the Jathas to reside in Amritsar without being harassed.[3] During this period, Nawab Kapur Singh, leader of the Sikhs at that time, decided to organize the various Jathas into two groups ('Dals', referring to a "branch" or "section"): the Budha Dal (army of the old) and the Taruna Dal (army of the young).[3] The Taruna Dal itself was further split into five sub-sections.[3] Each sub-section of the Taruna Dal flew its own banner.[3]

Government oppression resumes

[edit]However, state oppression of the Sikhs shortly after began again and the jathas started dividing themselves into more and more groups.[3] Then on the annual Diwali convening of the Sarbat Khalsa in 1745, a Gurmata was passed that reorganized the Jathas into 25 groups.[3] Yet the number of Jathas kept on ballooning until around 65 Jathas had begun to be known, as recorded by the contemporary Ali ud-Din Mufti in his Ibrat Namah.[3]

| No. | Leader | Affiliation | Associated habitation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Nawab Kapur Singh Faizullapuria | |||

| 2. | Jassa Singh Ahluwalia | Kalal village | ||

| 3. | Hari Singh Dhillon | Bhangi | Panjwar village | |

| 4. | Jhanda Singh | Bhangi | ||

| 5. | Ganda Singh | Bhangi | Panjwar village | |

| 6. | Natha Singh | Bhangi | ||

| 7. | Gujjar Singh | Bhangi | ||

| 8. | Garja Singh | |||

| 9. | Nibahu Singh | Bhangi | Nibahu Singh was the brother of Gujjar Singh Bhangi. | |

| 10. | Lehna Singh Khallon | Bhangi | ||

| 11. | Mehtab Singh | Khakh village, Amritsar district | ||

| 12. | Charat Singh Kanahiya | Kanhaiya | ||

| 13. | Diwan Singh | |||

| 14. | Phula Singh | Panawala village | ||

| 15. | Sanwal Singh Randhawa | Bhangi | Wagha village | |

| 16. | Gurbakhsh Singh | Bhangi | Doda village | This jatha later joined the Bhangis. |

| 17. | Dharam Singh | Bhangi | Klalwala village | |

| 18. | Tara Singh | Bhangi | Chainpuria village | |

| 19. | Bagh Singh | Kot Syed Muhammad village | ||

| 20. | Haqiqat Singh Kanahiya | Kanhaiya | ||

| 21. | Mehtab Singh | Bhangi | Wadala Sandhuan village | |

| 22. | Jai Singh | Kahna village | ||

| 23. | Jandu Singh | Kahna village | ||

| 24. | Tara Singh | Kahna village | ||

| 25. | Sobha Singh | Kahna village | ||

| 26. | Bhim Singh | Kahna village | ||

| 27. | Amar Singh | Wagha village | ||

| 28. | Sobha Singh | Bhika village | ||

| 29. | Baghel Singh | Jhabal village | ||

| 30. | Gulab Singh | Dallewal village | ||

| 31. | Hari Singh | Dallewal village | ||

| 32. | Naudh Singh | Sukerchakia | Led by the great-grandfather of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. | |

| 33. | Gulab Singh | Majitha village | ||

| 34. | Mehtab Singh | Julka village | ||

| 35. | Karora Singh | Pangarh village | ||

| 36. | Hara Singh | |||

| 37. | Lajja Singh | |||

| 38. | Nand Singh | Sanghna village | ||

| 39. | Kapur Singh | Bhangi | Surianwala village | |

| 40. | Amar Singh | Bhangi | Kingra village | Later joined the Bhangis. |

| 41. | Jiwan Singh | Bhangi | Qila Jiwan Singh village | |

| 42. | Sahib Singh | Bhangi | Sialkot | Later joined the Bhangis. |

| 43. | Baba Deep Singh | Leader martyred. | ||

| 44. | Natha Singh | Leader martyred. | ||

| 45. | Madan Singh | |||

| 46. | Mohan Singh | Ranian village | ||

| 47. | Bagh Singh Hallowal | Bhangi | ||

| 48. | Jhanda Singh | Sultan Vind village (near Amritsar) | ||

| 49. | Mirja Singh Tarkhan | |||

| 50. | Sham Singh Mann | Bulqichak village | ||

| 51. | Mala Singh | |||

| 52. | Bahal Singh | Shekupura village | ||

| 53. | Amar Singh | |||

| 54. | Hira Singh | |||

| 55. | Ganga Singh | |||

| 56. | Lal Singh | |||

| 57. | Tara Singh Mann | Mannawala village, Amritsar district | Later joined the Bhangis. | |

| 58. | Mehtab Singh | Lalpur village, Tarn Taran district | ||

| 59. | Roop Singh | |||

| 60. | Anoop Singh Nakai | Nakai | ||

| 61. | Dasaunda Singh | Nishanwalia | ||

| 62. | Tara Singh Gheba | Dallewal | ||

| 63. | Dharam Singh Khatri | Amritsar | ||

| 64. | Sukha Singh | Mari Kamboke village | ||

| 65. | Jassa Singh Ramgarhia |

Finally, on the annual Diwali meeting of the Sarbat Khalsa in Amritsar in 1748, the Jathas were reorganized into a new grouping called misls, with 11 Misls forming out of the various pre-existing Jathas and a unified army known as the Dal Khalsa Ji.[3] Ultimate command over the Misls was bestowed to Jassa Singh Ahluwalia.[3] The words Jatha and Jathedar began to fall into disuse after this point, as leaders of Misls preferred the term 'Sardar' to refer to themselves, due to Afghan influence.[3]

Dissolution

[edit]After the rise of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and the establishment of the Sikh Empire, various aspects of 18th century Sikhism, including Jatha formations, were abolished.[3]

Equipment

[edit]18th century warriors of a jatha were equipped at-first with knobbed clubs, spears, battle axes, bow and arrows, and matchlocks.[3] As mandatory for a Khalsa, all the warriors were equipped with a long-sword and dagger (kirpan).[3] Some but not all of the warriors wore body armour, excluding helmets.[3] Horses were incredibly valued and mounts of high-quality were targeted during raids on the enemy transport convoys (columns and baggage trains).[3]

Later-on as the Jathas succeeded in capturing hostile resources, they came into the possession of more firearms in the form of matchlocks to equip their ranks with.[3] The Sikhs avoided the use of heavy-artillery pieces as it impeded their military strategy of being quick and mobile.[3] As per Rattan Singh Bhangu in his Panth Prakash, some light-artillery pieces were used by the Sikhs of this era, such as zamburaks (camel-mounted swivel cannons) and a long-range musket known as a janjail.[3]

Revival

[edit]The terms "jatha" and "jathedar" were revived during the Singh Sabha movement to refer to "bands of preachers and choirs", an association which survives until the present-day.[3] However, during the later Gurdwara reform movement, the terms began to take on a martial tone once again, resuscitating and harking back to the 18th century's context for the word.[3] The group of Sikhs protesting and fighting for the freedom of Sikh shrines and places of worship from the control of hereditary mahants were termed Akali Jathas.[3] The term Jatha began to refer to a "band of [Sikh] volunteers going forward to press a demand or to defy an unjust fiat of the government".[3] This semantic of the word is still used.[3]

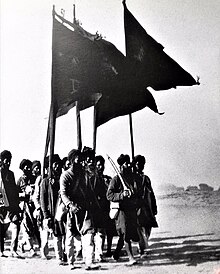

Sikh Jatha during British rule

[edit]

Jathas existed during the British Raj in the Punjab, northern India. During this time, the British imprisoned many Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims, and many villages and towns being raided by the British colonial police.[5] During these difficult times, Sikhs began forming jathas and new armed squads in British India, and many villages and towns relied on the protection of the Sikh jathas. Sikhs carried out many attacks and assassinations on the British, resulting in many Sikhs arrested and executed.[citation needed] The Sikhs played an influential role in the Indian independence movement. Prominent figures include Bhagat Singh and Udham Singh, who traveled to London and hunted down people who got away with the killings in India. Most Sikh prison inmates were executed after the assassination of the high ranking British officer John Simon, 1st Viscount Simon, head of the Simon Commission from the British Parliament.[5] There was also a bombing targeting the British courts. Bhagat Singh was said to have been behind most of the actions carried out against the British and was later hanged.

Some Sikh jathas such as the Babbar Akali Movement, formed in 1921, rejected non-violence and gave stiff resistance to the British, which led to small battles and assassinations, and eventually by 1939 were down to large shootouts.[6]

The term Shahidi Jatha ("band of martyrs"), used during the Gurdwara Reform movement, referred to a jatha that had previously been arrested but continue to agitate even after their release as part of a movement, such as at the Jaito Morcha.[7]

Partition of Punjab

[edit]

During the partition of Punjab in 1947, many Sikhs began to form armed Jatha squads for both defensive and offensive purposes against Muslims.[8]

When British rule came to an end in India, it had to make the crucial decision of determining the borders of the new country of Pakistan.[5] Some historians say the biggest mistake the British made before they left India was splitting the Sikh main land of Punjab in two, giving one half to the Islamic government of Pakistan and the other half to be run by a Hindu government.[5] This led to non-stop bloodshed between many Sikhs and Muslims. Thousands of Muslims fled the East Punjab for Pakistan and thousands of Sikhs left Pakistan to go to "New" Punjab, but this journey resulted in thousands of lives lost due to massacres committed by both sides.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Civil Wars of the World: Major Conflicts Since World War II, Volume 1

- ^ "Who are Sikhs? What is Sikhism?". Sikhnet.com. 5 August 2012. Archived from the original on 2016-08-07. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Singh, Harbans. The Encyclopedia of Sikhism. Vol. 2: E-L. Punjabi University, Patiala. pp. 362–3.

- ^ Singh, Dalbir (2010). "1: Historical Background (Emergence of Bhangi Misal)". Rise, Growth and Fall of the Bhangi Misal. Patiala: Department of History, Punjabi University. pp. 32–34.

- ^ a b c d Abel, Ernest. "Sikh history in British India". Archived from the original on 2019-09-07. Retrieved 2011-06-23.

- ^ Singha, Guracarana (1993). Babbar Akali Movement: A Historical Survey (2 ed.). Michigan: Aman Publications, 1993. pp. 192–194. ISBN 9788171163007.

- ^ "Sikh Religious Grievances Exploited by Political Agitators: Akalis Arrested in the Punjab". The Illustrated London News. 16 August 1924. Retrieved 4 February 2025.

- ^ Hajari, Nisid (29 June 2015). "Did Sikh squads participate in an organised attempt to cleanse East Punjab during Partition?". The Caravan. Retrieved 2023-07-15.

- ^ J. Devi (2005), "The River Churning", Literary polyrhythms: new voices in new writings in English, Sarup & Sons, ISBN 9788176255950